The flying business is a very peculiar one. A key component is that it does not admit any margin of risk in the operational activities. Assume that you are given a bet: you have the chance to get, say, a 3% return on your monthly pay, and the chances of winning are 99.99%. Most of you would probably accept the bet. But put it on another perspective: would you ever flight on a plane that has one chance every 10,000 to be defective (I do not mean one chance out of 10,000 to die, but just that the airplane has a malfunctioning)? Most of you would not even accept one chance out of 100,000 that the plane you are flying with is flawed*. That is why, passengers of Garuda Indonesia started demanding which plane they would have flown with, and asked the carrier to switch in case it was a Boeing 737 Max - the model dramatically involved in the two seemingly related accidents that killed more than 300 people in less than 6 months. Garuda Indonesia has even drastically decided to cancel its orders of 737 Max with the airplane manufacturer Boeing.

The facts

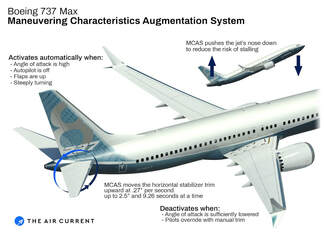

On March 10th, 2019, a Boeing 737 Max of Ethiopian Airlines from Addis Ababa to Nairobi crashed few minutes after the departure, killing 157 people. Similarities have been found with another 737 Max flight that 5 months before crashed near Indonesia. The investigations are now focused on the MCAS system – an anti-stall system that automatically moves the aircraft’s nose whenever is needed. Such a system relies on a single sensor which, in case of flaws, might send erroneous signals to the on-board computers as happened in this case. The situation is complicated even more by the fact that now, with the advent of automation, many actions are not only taken without the pilot’s involvement and can even override the pilot’s decisions. Nonetheless, some few things have to be added. First, it has not been clarified yet if pilots were undertrained for such a new system (the MCAS was in fact introduced not too much time ago) but, most probably, they couldn’t have done anything in any case. Second, Boeing is working to become operational again. A software fix has been delivered on Tuesday, causing a stock surge of 2%, and a new sensor is planned to be added, so as to have a double check on stalling conditions in case one sensor is broken. Finally, an important point on grounding. Immediately after the last accident, most countries suspended the authorization for the Boeing 737 Max to fly. The first were China and Canada, immediately followed by many other, except for one. USA took a couple of hours more for the decision. It initially declared through the FAA (the entity responsible for flying authorization), that there were no “systematic performance issues” and “no basis to order grounding the aircraft”. It was only on March 13th, 2019, that president Donald Trump issued the order of grounding. Any explanation for this? The FAA was the entity globally responsible for granting the final authorization to fly to the 737 Max aircraft, when first introduced into the market. It seemed like if the Federal Aviation Administration has not admitted their potential mistake, until too much pressure from other countries’ decisions forced it to adopt the same line.

The facts

On March 10th, 2019, a Boeing 737 Max of Ethiopian Airlines from Addis Ababa to Nairobi crashed few minutes after the departure, killing 157 people. Similarities have been found with another 737 Max flight that 5 months before crashed near Indonesia. The investigations are now focused on the MCAS system – an anti-stall system that automatically moves the aircraft’s nose whenever is needed. Such a system relies on a single sensor which, in case of flaws, might send erroneous signals to the on-board computers as happened in this case. The situation is complicated even more by the fact that now, with the advent of automation, many actions are not only taken without the pilot’s involvement and can even override the pilot’s decisions. Nonetheless, some few things have to be added. First, it has not been clarified yet if pilots were undertrained for such a new system (the MCAS was in fact introduced not too much time ago) but, most probably, they couldn’t have done anything in any case. Second, Boeing is working to become operational again. A software fix has been delivered on Tuesday, causing a stock surge of 2%, and a new sensor is planned to be added, so as to have a double check on stalling conditions in case one sensor is broken. Finally, an important point on grounding. Immediately after the last accident, most countries suspended the authorization for the Boeing 737 Max to fly. The first were China and Canada, immediately followed by many other, except for one. USA took a couple of hours more for the decision. It initially declared through the FAA (the entity responsible for flying authorization), that there were no “systematic performance issues” and “no basis to order grounding the aircraft”. It was only on March 13th, 2019, that president Donald Trump issued the order of grounding. Any explanation for this? The FAA was the entity globally responsible for granting the final authorization to fly to the 737 Max aircraft, when first introduced into the market. It seemed like if the Federal Aviation Administration has not admitted their potential mistake, until too much pressure from other countries’ decisions forced it to adopt the same line.

The economics of the crash

The two crashes should not - at least in theory - impact Boeing’s profits and results too much, especially if we consider a time horizon of two/ three years from now. The airplane industry is a very peculiar one, particularly if we consider commercial planes only: since the 1990s, the duopolists Boeing and Airbus have had almost equal percentages of market share, with Airbus receiving slightly more orders than Boeing from 2007 to 2016 but delivering slightly less planes. If you do not like one, you have no opportunity but going to the other. Consider also the long queue that each of the producers has for delivering planes: the same 737 Max, for example, was delivered roughly 350 times, while the not-yet-delivered orders for this model are about 4000. Building a plane is a process that takes time, and companies order many of them also in light of waiting times. Think now of Garuda Indonesia. The only option they have on the table, if they want to buy a similar plane but not from Boeing, is to go to Airbus and reformulate an equivalent order of almost 50 planes. The direct competitor of the 737 Max is the Airbus A320 Neo, first introduced for commercial use by TAP Portugal in early 2018. Both the models are some of the most advanced planes that carriers can hope to find in the markets: they are fuel-efficient, long-ranged, and interiorly enhanced. A company like Garuda Indonesia orders one of these airplanes because of these specific characteristics that they have, and it seems very unlikely that after cancelling the order the company would switch to an older Boing model. This would probably change significantly the planned strategy of the firm. As a result, the only option to the table is going to Airbus, and demand for an A320 Neo. The reality of facts, however, is different. As of February, Airbus has roughly 5800 firm orders for the A320 family, and even at the increased rate of production planned for 2021 of 725 planes a year, it would take 8 years to fulfill the existing orders. How many commercial carriers can sustain to wait such a long time? Probably few, and it is reasonable to assume that even less will follow the actions of Garuda. If this is not enough, just remember that ordering a plane is not costless: companies pay an upfront sum that they will probably not get back, unless very specific and complex clauses allowing companies to redeem the order and receive the reimbursement of the initial payment (which is very unlikely). So, at least in general terms, the market share of Boeing should be safe.

The one-time costs Boeing will face this year should be mainly related to the software fixture and to the sensor addition, while additional training to pilots should be provided by the companies the pilots work for. The software fixture has already been released, and it is an update that does not require neither to call planes back, nor to temporarily stop the production. Moreover, the costs associated should be minimal. The additional sensor that will be introduced, on the other hand, will demand for 350 already-flying planes to be sent on “assistance”. All the manufacturing costs related with this will be borne by Boeing, but given the dimension of the player they should not impact its profitability in a sensible way. The two aspects together, however, may impact the production of the 737 Max already ordered and lengthen the delivery times, until a final solution is found. This delay is an implicit cost for Boeing.

Finally, a point on share price. The accident took place on a Sunday, and the shares had closed at 422,54$ on Friday. When the NYSE re-opened the next Monday, the shares fell to 375,41$ in two days, a drop of 11,1%. They touched their lowest on March 22nd, when Garuda Indonesia announced the order cancel, and they traded at 362,17$. As of April 17 they were back to 377.52$. If we take into account 2019 only, the share price is up 16.59% from 323,81$, at which the securities were exchanged on January the 2nd. As soon as it was clear that the fundamental values of the company would not have been significantly impacted, the market started to correct the initial price drop, and re-aligned the company to the general positive outlook of equity markets.

The two crashes should not - at least in theory - impact Boeing’s profits and results too much, especially if we consider a time horizon of two/ three years from now. The airplane industry is a very peculiar one, particularly if we consider commercial planes only: since the 1990s, the duopolists Boeing and Airbus have had almost equal percentages of market share, with Airbus receiving slightly more orders than Boeing from 2007 to 2016 but delivering slightly less planes. If you do not like one, you have no opportunity but going to the other. Consider also the long queue that each of the producers has for delivering planes: the same 737 Max, for example, was delivered roughly 350 times, while the not-yet-delivered orders for this model are about 4000. Building a plane is a process that takes time, and companies order many of them also in light of waiting times. Think now of Garuda Indonesia. The only option they have on the table, if they want to buy a similar plane but not from Boeing, is to go to Airbus and reformulate an equivalent order of almost 50 planes. The direct competitor of the 737 Max is the Airbus A320 Neo, first introduced for commercial use by TAP Portugal in early 2018. Both the models are some of the most advanced planes that carriers can hope to find in the markets: they are fuel-efficient, long-ranged, and interiorly enhanced. A company like Garuda Indonesia orders one of these airplanes because of these specific characteristics that they have, and it seems very unlikely that after cancelling the order the company would switch to an older Boing model. This would probably change significantly the planned strategy of the firm. As a result, the only option to the table is going to Airbus, and demand for an A320 Neo. The reality of facts, however, is different. As of February, Airbus has roughly 5800 firm orders for the A320 family, and even at the increased rate of production planned for 2021 of 725 planes a year, it would take 8 years to fulfill the existing orders. How many commercial carriers can sustain to wait such a long time? Probably few, and it is reasonable to assume that even less will follow the actions of Garuda. If this is not enough, just remember that ordering a plane is not costless: companies pay an upfront sum that they will probably not get back, unless very specific and complex clauses allowing companies to redeem the order and receive the reimbursement of the initial payment (which is very unlikely). So, at least in general terms, the market share of Boeing should be safe.

The one-time costs Boeing will face this year should be mainly related to the software fixture and to the sensor addition, while additional training to pilots should be provided by the companies the pilots work for. The software fixture has already been released, and it is an update that does not require neither to call planes back, nor to temporarily stop the production. Moreover, the costs associated should be minimal. The additional sensor that will be introduced, on the other hand, will demand for 350 already-flying planes to be sent on “assistance”. All the manufacturing costs related with this will be borne by Boeing, but given the dimension of the player they should not impact its profitability in a sensible way. The two aspects together, however, may impact the production of the 737 Max already ordered and lengthen the delivery times, until a final solution is found. This delay is an implicit cost for Boeing.

Finally, a point on share price. The accident took place on a Sunday, and the shares had closed at 422,54$ on Friday. When the NYSE re-opened the next Monday, the shares fell to 375,41$ in two days, a drop of 11,1%. They touched their lowest on March 22nd, when Garuda Indonesia announced the order cancel, and they traded at 362,17$. As of April 17 they were back to 377.52$. If we take into account 2019 only, the share price is up 16.59% from 323,81$, at which the securities were exchanged on January the 2nd. As soon as it was clear that the fundamental values of the company would not have been significantly impacted, the market started to correct the initial price drop, and re-aligned the company to the general positive outlook of equity markets.

All these things said, we can conclude that despite the dramality of the two happenings, and their seemingly related nature, Boeing should recover from all the related problems without incurring huge difficulties in its operations.

Giuseppe Murgo

*actual chances of dying on a plane are roughly 1 every 10 million, but statistics change from carrier, country, and reports. To put it into perspective, the chances of dying due to a bee sting are 1 every 80,000

Giuseppe Murgo

*actual chances of dying on a plane are roughly 1 every 10 million, but statistics change from carrier, country, and reports. To put it into perspective, the chances of dying due to a bee sting are 1 every 80,000