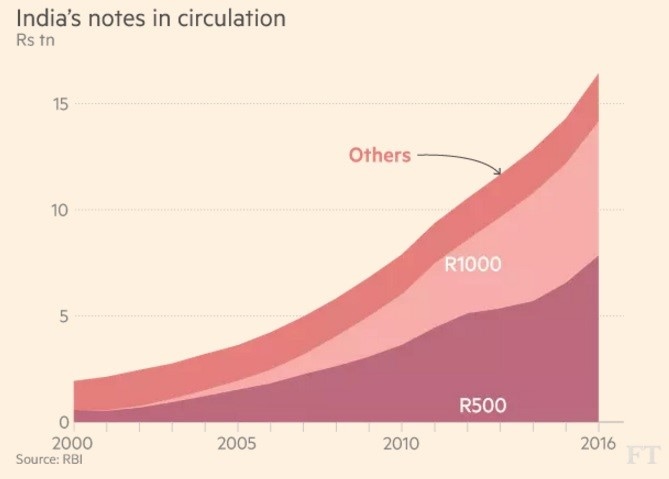

On November the 8th, the Prime Minister of India, Narendra Modi, announced the demonetization of ₹500 (US$7.40) and ₹1,000 (US$15) banknotes which had been replaced by new ₹500 and ₹2000 banknotes of the Mahatma Gandhi New Series. The TV live video message through which the Indian Prime Minister has announced the fact was unscheduled and unexpected. The underlying reason is to wipe out the black economy and increase the country’s tax base, improving public finances. The government’s decision implies a withdrawal of Rs15.5tn worth roughly $220bn which represents 86% of India’s circulation cash. Indians had time until 30th of December 2016 to change their no longer legal tender banknotes by either depositing them in bank accounts or exchanging them in small quantities over the counter at a discount. All of this has caused some chaos in the country: long queues in front of banks and ATMs, cash crunch, not fully understood slowdown in the economic activity and nationwide strikes.

In fact, India is a cash-driven economy, where cash is used in nearly 80% of consumer transactions and circulating cash is 14% of GDP, while in other large economies it represents less than 5%. India as being a developing country does not have a well distributed bank system, the majority of bank branches is concentrated in the most important 60 cities, therefore roughly 32% of the population has access to financial institutions. In addition, most wages are paid in cash and on a daily basis.

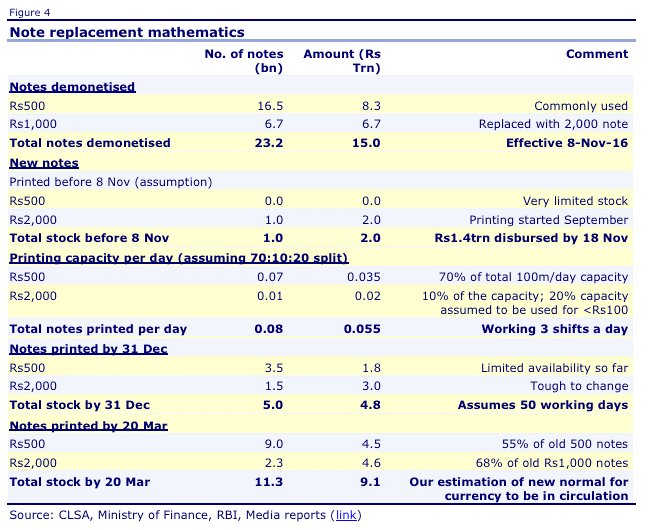

The currency swap had some technical and logistical constraints. Firstly, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been slow to print the new banknotes. The country, having only four printing presses of an annual capacity of 36bn notes on a three-shift basis, has to keep printing until approximately the 20th of March. Otherwise, another option could be to get some money printed offshore.

The currency swap had some technical and logistical constraints. Firstly, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been slow to print the new banknotes. The country, having only four printing presses of an annual capacity of 36bn notes on a three-shift basis, has to keep printing until approximately the 20th of March. Otherwise, another option could be to get some money printed offshore.

Secondly, logistical constraints may have to be considered: the currency printed has to be transferred to 19 currency issuing offices of the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), then it has to be moved to 4,100 currency chests located within banks and lastly distributed among more than 130,000 bank branches and 200,000 ATMs across the country. India does not have enough vans and employees to accomplish this task. Furthermore, ATMs had to be re-calibrated to dispense the new banknotes as they are smaller in size.

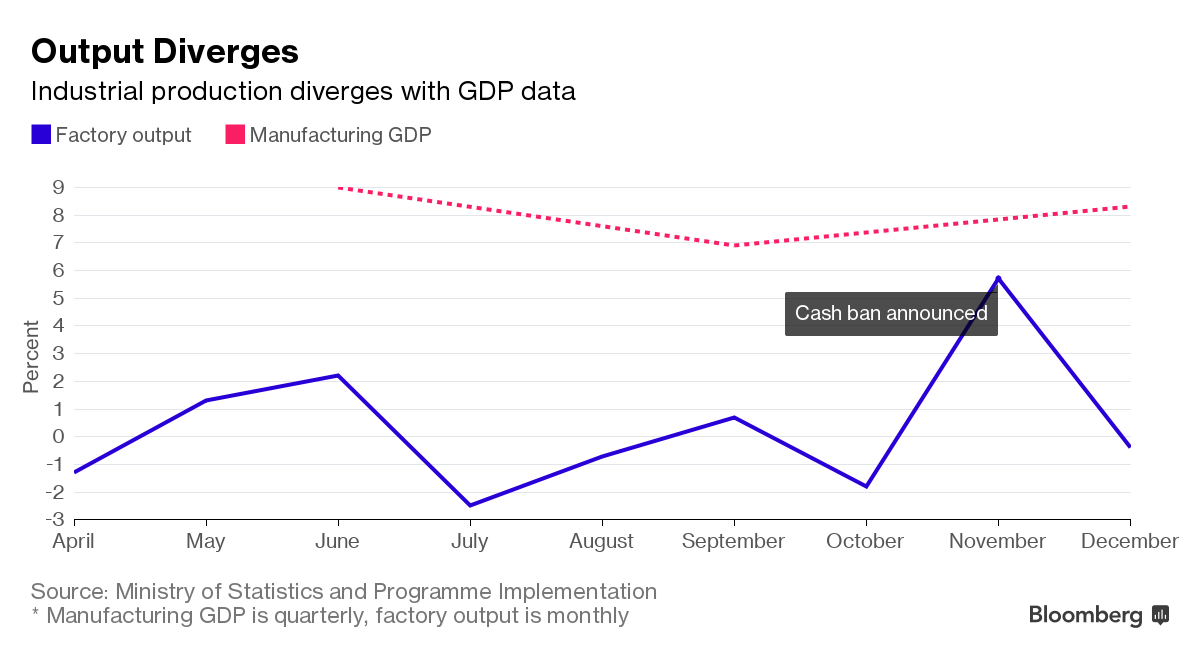

After this government’s decision the country is experiencing a cash crunch since there is not enough replacement cash available. Many economists and analysts predicted a negative impact on the country’s GDP. However, surprisingly recent data showed that during October-December the country’s GDP grew 7%. Though there is a widespread opinion that this data captures only partially the full effects of the demonetisation and there is skepticism on how the annual GDP growth rate is calculated after 2015, when the government changed the methodology.

After this government’s decision the country is experiencing a cash crunch since there is not enough replacement cash available. Many economists and analysts predicted a negative impact on the country’s GDP. However, surprisingly recent data showed that during October-December the country’s GDP grew 7%. Though there is a widespread opinion that this data captures only partially the full effects of the demonetisation and there is skepticism on how the annual GDP growth rate is calculated after 2015, when the government changed the methodology.

The day after the demonetisation announcement, the stock market plunged, the BSE SENSEX and NIFTY 50 stock indices fell over 6% as a consequence of negative investors’ expectations. After a general decreasing trend the Indian stock market is expected to have an upward swing, especially after the latest economic data.

India’s banking system has had countervailing effects, on the one hand banks had to cover the expenses related to the demonetisation and have experienced a drop in the demand for credit, on the other hand there has been a surge in deposits inducing a couple of banks to cut their lending rates. The former might have prevailing consequences on banks’ stability since they were already coping with the weakest loan growth in the last twenty years and total costs of the monetary policy could reach Rs351 billion ($5.2 billion). As for the latter, it is estimated that people deposited Rs12.4 trillion ($183 billion) in cash into the system and the current cash crunch might stimulate more and more people to use bank accounts and its related services such as credit and debit cards as well as online payment systems.

Impacts on the RBI balance sheet

There was rumor of an eventual higher dividend for the Indian government by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as a result of the demonetisation. Every year in July, the Central Bank pays to the government a dividend from the profit of its P&L, mostly formed by active interests earned on bond investments. Rumor was supported by the fact that it is not clear how the RBI will account for this unprecedented economic experiment on its balance sheet. If the unconverted currency in circulation is not any longer legal tender, then the CB will have fewer liabilities. The final impact of the demonetisation could be accounted either as a gain in the P&L or by extinguishing the backing assets. However, it is not clear when the liability will be considered cancelled, because even if the 30th December 2016 was the official last date for tendering old notes with commercial banks, there is no expiration date to deposit with the RBI.

Putting the puzzle together, it is still too early to assess the effects of the Indian demonetisation, certainly Modi’s underlying objectives of fighting the black economy and of economic digitalization are admirable.

There was rumor of an eventual higher dividend for the Indian government by the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) as a result of the demonetisation. Every year in July, the Central Bank pays to the government a dividend from the profit of its P&L, mostly formed by active interests earned on bond investments. Rumor was supported by the fact that it is not clear how the RBI will account for this unprecedented economic experiment on its balance sheet. If the unconverted currency in circulation is not any longer legal tender, then the CB will have fewer liabilities. The final impact of the demonetisation could be accounted either as a gain in the P&L or by extinguishing the backing assets. However, it is not clear when the liability will be considered cancelled, because even if the 30th December 2016 was the official last date for tendering old notes with commercial banks, there is no expiration date to deposit with the RBI.

Putting the puzzle together, it is still too early to assess the effects of the Indian demonetisation, certainly Modi’s underlying objectives of fighting the black economy and of economic digitalization are admirable.

Vittoria Roà