Introduction

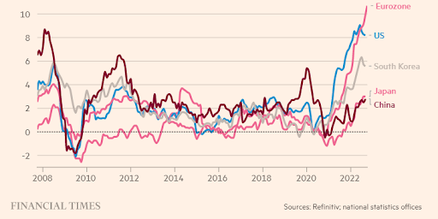

10.7%, this is the level inflation has reached in the Eurozone in October 2022 with respect to a year before: way higher than the expectations of analysts and more than five times higher than the 2% targeted by central banks in the western world. Of not such a smaller magnitude is what the US economy is experiencing right now, with 8% inflation rate year over year in the same period, with however a very mild, albeit promising, decrease with respect to the 8.2% of the previous month. On both sides of the Atlantic monetary policy has surged on the first pages, with rises in interest rates unseen in the past few decades: the Fed has now reached 4% policy rate with four consecutive increases of 75 basis points; Bank of England resumed its contractionary monetary policy, and analogous has been the intervention of the ECB, recently announcing an increase of 0,75%, reaching 1.5% deposit rate, unseen from 2009. What seems to be ahead is further contractions, most likely less consistent, however, with recession on the horizon for many European economies. There is a risk central banks go too far: shall the slowdown turn into a serious recession, that could mean a wave of business insolvencies, steep falls in house prices and higher joblessness. After decades of low interest rates and high liquidity, the shrinking of central banks’ balance sheets may compromise financial stability (the UK gilts crisis is an example).

Why has inflation been so persistent? The answer may be trivial, in the sense that spending has remained high. This is however an unsatisfactory result: the drivers of present time inflation are various and differ a lot among countries. The US is still suffering the consequences of an expansionary fiscal stimulus of unprecedented proportions during the early phases of the pandemic, in the Eurozone the disruption to the supply chain, together with the spike in energy prices due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been crucial. Not to be disregarded is the role of future expectations: The Economist in the latest issue has highlighted how even a recession, if it is believed to be brief, may not slow down inflation rates. Uncertain times are ahead.

10.7%, this is the level inflation has reached in the Eurozone in October 2022 with respect to a year before: way higher than the expectations of analysts and more than five times higher than the 2% targeted by central banks in the western world. Of not such a smaller magnitude is what the US economy is experiencing right now, with 8% inflation rate year over year in the same period, with however a very mild, albeit promising, decrease with respect to the 8.2% of the previous month. On both sides of the Atlantic monetary policy has surged on the first pages, with rises in interest rates unseen in the past few decades: the Fed has now reached 4% policy rate with four consecutive increases of 75 basis points; Bank of England resumed its contractionary monetary policy, and analogous has been the intervention of the ECB, recently announcing an increase of 0,75%, reaching 1.5% deposit rate, unseen from 2009. What seems to be ahead is further contractions, most likely less consistent, however, with recession on the horizon for many European economies. There is a risk central banks go too far: shall the slowdown turn into a serious recession, that could mean a wave of business insolvencies, steep falls in house prices and higher joblessness. After decades of low interest rates and high liquidity, the shrinking of central banks’ balance sheets may compromise financial stability (the UK gilts crisis is an example).

Why has inflation been so persistent? The answer may be trivial, in the sense that spending has remained high. This is however an unsatisfactory result: the drivers of present time inflation are various and differ a lot among countries. The US is still suffering the consequences of an expansionary fiscal stimulus of unprecedented proportions during the early phases of the pandemic, in the Eurozone the disruption to the supply chain, together with the spike in energy prices due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been crucial. Not to be disregarded is the role of future expectations: The Economist in the latest issue has highlighted how even a recession, if it is believed to be brief, may not slow down inflation rates. Uncertain times are ahead.

APAC outlook

Moving to APAC, however, the scenario is trickier. Substantially different macroeconomic conditions and monetary policies are observed in most of the countries on the Pacific. In South Korea, inflation has been in a fairly low range for the past ten years, ranging from 0.61% to 1.43%. However, since the pandemic, inflation has risen, peaking in July 2022 at 6.3%, and then falling to 5.6% today. Inflation has increased especially as oil and commodity prices have risen due to the continuing war between Russia and Ukraine and disruptions in global supply chains. In August 2021, the Central Bank of South Korea became the first major Asian economy to raise interest rates, raising it from 0.5% in early 2020 to 3% today. The decision was taken to counter rising prices, particularly in the real estate sector, and rising private household debt, which, according to the Central Bank of South Korea, threaten to put the post-pandemic economic recovery at risk. Unlike South Korea, India has historically had very high inflation, the average inflation over the last 30 years being around 7%. However, inflation in India is very volatile, as it is a particularly flexible inflation-targeting regime. For this reason, inflation from 2019-2020 has risen from 2% to 8%. It also dropped to 4% towards the end of 2021, only to return to its previous level of 8% these days. The main reason for inflation in India is the war between Russia and Ukraine. This conflict has created a significant negative supply shock, as both countries are major commodity exporters. The prices of basic food commodities, which account for almost half of the inflation basket in India, have therefore risen sharply. To counter historical inflation, the Bank of India kept interest rates at 4 % during 2016-2022. In April 2022, it started raising interest rates even higher to the current 6%.

The 3.4% increase in the price index in Japan represents a 30-years high, but Bank of Japan does not seem to be willing to impair the more than fragile economic recovery. Last but not least, Beijing has now entered a new season of its politics, with Xi Jinping having begun his third mandate stuck with his zero-Covid policy that is probably the greatest source of uncertainty in the economic trends of the country. The second largest world economy is not offering much support to growth as it used to do, and the now more powerful than ever president seems to be determined on a more communist policy, focus on nationalized industry and, above all, a growing intervention in prices. China and Japan, second and third countries by GDP worldwide, together accounting for more than a fifth of the global level of output, both figure very interesting choices of monetary policies and peculiar features of their economy, especially to the eyes of a western observer. If some global trends are common to most economies worldwide, one above all the rise in energy prices, these two countries deserve a more in-depth analysis of the underlying reasons of their current price levels.

Moving to APAC, however, the scenario is trickier. Substantially different macroeconomic conditions and monetary policies are observed in most of the countries on the Pacific. In South Korea, inflation has been in a fairly low range for the past ten years, ranging from 0.61% to 1.43%. However, since the pandemic, inflation has risen, peaking in July 2022 at 6.3%, and then falling to 5.6% today. Inflation has increased especially as oil and commodity prices have risen due to the continuing war between Russia and Ukraine and disruptions in global supply chains. In August 2021, the Central Bank of South Korea became the first major Asian economy to raise interest rates, raising it from 0.5% in early 2020 to 3% today. The decision was taken to counter rising prices, particularly in the real estate sector, and rising private household debt, which, according to the Central Bank of South Korea, threaten to put the post-pandemic economic recovery at risk. Unlike South Korea, India has historically had very high inflation, the average inflation over the last 30 years being around 7%. However, inflation in India is very volatile, as it is a particularly flexible inflation-targeting regime. For this reason, inflation from 2019-2020 has risen from 2% to 8%. It also dropped to 4% towards the end of 2021, only to return to its previous level of 8% these days. The main reason for inflation in India is the war between Russia and Ukraine. This conflict has created a significant negative supply shock, as both countries are major commodity exporters. The prices of basic food commodities, which account for almost half of the inflation basket in India, have therefore risen sharply. To counter historical inflation, the Bank of India kept interest rates at 4 % during 2016-2022. In April 2022, it started raising interest rates even higher to the current 6%.

The 3.4% increase in the price index in Japan represents a 30-years high, but Bank of Japan does not seem to be willing to impair the more than fragile economic recovery. Last but not least, Beijing has now entered a new season of its politics, with Xi Jinping having begun his third mandate stuck with his zero-Covid policy that is probably the greatest source of uncertainty in the economic trends of the country. The second largest world economy is not offering much support to growth as it used to do, and the now more powerful than ever president seems to be determined on a more communist policy, focus on nationalized industry and, above all, a growing intervention in prices. China and Japan, second and third countries by GDP worldwide, together accounting for more than a fifth of the global level of output, both figure very interesting choices of monetary policies and peculiar features of their economy, especially to the eyes of a western observer. If some global trends are common to most economies worldwide, one above all the rise in energy prices, these two countries deserve a more in-depth analysis of the underlying reasons of their current price levels.

The case of Japan

I.Inflation Outlook and monetary policy

Japan’s problem in recent decades has generally been flat or falling prices, manifestation of a more general situation of economic stagnation, with roots in deep structural factors, in which wages and investment also failed to raise. Hence, many argue that this is exactly the moment the Bank of Japan (BoJ) had been waiting for: Japan might be getting closer to achieve the long-awaited condition of slow and steady inflation that its central bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, has been pursuing since, in March 2013, he vowed to do “whatever it takes” to end the country’s bouts of mild yet corrosive deflation that had been going on since the ‘90s.

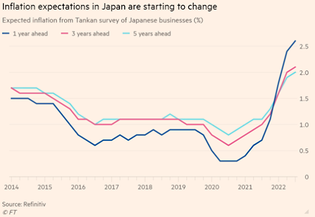

Helped by a surge in commodity prices fueled by the war in Ukraine, the country is currently experiencing a 3% headline inflation, above the 2% target of the central bank. Yet, excluding fresh food and energy costs, prices went up just 1.6% year-on-year, around one fifth of the average across the OECD club, with wage growth remaining anemic. For this reason, the Bank of Japan can and likely will continue to swim against the tide, with its main worry being not the emergence of a wage-inflation spiral, as in the US and (by a lesser extent) Europe, but rather the opposite: a lack of strong wage growth, desperately needed to shield the economy from falling back into a deflationary trap. In this regard, Mr. Kuroda stressed that monetary stimulus is still needed to ensure that deflation will not return once the rout of price rises triggered by global events passes, suggesting that monetary policy will try to encourage price changes, taking advantage of this precious opportunity.

I.Inflation Outlook and monetary policy

Japan’s problem in recent decades has generally been flat or falling prices, manifestation of a more general situation of economic stagnation, with roots in deep structural factors, in which wages and investment also failed to raise. Hence, many argue that this is exactly the moment the Bank of Japan (BoJ) had been waiting for: Japan might be getting closer to achieve the long-awaited condition of slow and steady inflation that its central bank governor, Haruhiko Kuroda, has been pursuing since, in March 2013, he vowed to do “whatever it takes” to end the country’s bouts of mild yet corrosive deflation that had been going on since the ‘90s.

Helped by a surge in commodity prices fueled by the war in Ukraine, the country is currently experiencing a 3% headline inflation, above the 2% target of the central bank. Yet, excluding fresh food and energy costs, prices went up just 1.6% year-on-year, around one fifth of the average across the OECD club, with wage growth remaining anemic. For this reason, the Bank of Japan can and likely will continue to swim against the tide, with its main worry being not the emergence of a wage-inflation spiral, as in the US and (by a lesser extent) Europe, but rather the opposite: a lack of strong wage growth, desperately needed to shield the economy from falling back into a deflationary trap. In this regard, Mr. Kuroda stressed that monetary stimulus is still needed to ensure that deflation will not return once the rout of price rises triggered by global events passes, suggesting that monetary policy will try to encourage price changes, taking advantage of this precious opportunity.

In response, inflation expectations increased, reaching unprecedented heights. This is of particular importance as the entrenched deflationary mindset has arguably been the biggest hurdle for rising prices to be reflected in employee earnings so far. And strong wage growth is seen as the ultimate ‘amulet’ against Japan slipping back into deflation. Mr. Kuroda said that wages should rise by 3% for Japan to achieve a stable 2% inflation, in line with target, given labor productivity increases of around 1%. In this regard, the Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who recently released a new economic package that includes incentives for companies that raise wages and support for household electricity bills, identified next spring’s wage negotiations as the decisive battleground for whether the country can enter into a virtuous cycle of growth and distribution. Indeed, the Japanese Trade Union Confederation, which represents about seven million members, is seeking a wage increase of about 5% in next spring’s annual negotiations. While part of that represents routine increases tied to seniority, the union confederation also wants a 3% rise in base salary: its biggest request since 1995. Economists are divided on how much companies would be willing to increase wages after resisting for so long.

At any rate, the Bank of Japan made it clear that it won’t start tightening until there are signs that broad-based domestic inflation is starting to take hold. Therefore, unless the spring talks succeed and a trend for steady wage rises can be confirmed, the central bank will be unlikely to begin rate hikes or rein in its gigantic QQE (Quantitative and Qualitative Easing) operations. Yet, this stance is generating tensions. Consider the 10-year Japanese government bonds, whose yield the BoJ has capped at 0.25% since March 2021. With the US Federal Reserve aggressively raising interest rates, market forces in Japan have been pushing up the yields on government bonds, putting pressure on the peg. As a result, for the fourth straight session, none of the latest issues of 10-year JGBs traded. The responsibility for making a normally large market wither away lies in the BoJ, which, to enforce the cap, is offering a higher price for the 10-year bond than any private firm is willing to pay.

At any rate, the Bank of Japan made it clear that it won’t start tightening until there are signs that broad-based domestic inflation is starting to take hold. Therefore, unless the spring talks succeed and a trend for steady wage rises can be confirmed, the central bank will be unlikely to begin rate hikes or rein in its gigantic QQE (Quantitative and Qualitative Easing) operations. Yet, this stance is generating tensions. Consider the 10-year Japanese government bonds, whose yield the BoJ has capped at 0.25% since March 2021. With the US Federal Reserve aggressively raising interest rates, market forces in Japan have been pushing up the yields on government bonds, putting pressure on the peg. As a result, for the fourth straight session, none of the latest issues of 10-year JGBs traded. The responsibility for making a normally large market wither away lies in the BoJ, which, to enforce the cap, is offering a higher price for the 10-year bond than any private firm is willing to pay.

II.FX market reaction and interventions

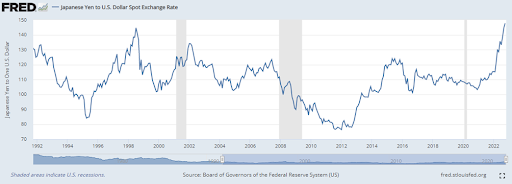

The most obvious effect of the Japanese central bank’s policy has been a sharp fall in the yen, with a 28% descent so far against the dollar this year, hitting its lowest value in 30 years.

The most obvious effect of the Japanese central bank’s policy has been a sharp fall in the yen, with a 28% descent so far against the dollar this year, hitting its lowest value in 30 years.

While Japanese authorities, in their repeated references to market speculators, heavily overstate - according to most analysts - the role of hedge funds and other leveraged investors (the Japanese Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki stated: “we are engaged in a fierce standoff with speculators”), the fundamental forces dragging the yen down come from the growing gap in interest rates between the BoJ and other central banks, and the massive outflows of capital by Japanese companies and asset managers it implied. The 150 yen to the dollar exchange rate appears to be consistent with current market expectations that the Federal Reserve would ultimately lift interest rates above 5% while the Bank of Japan is keeping its benchmark rates near zero.

The government did not stand by. In the past two months, more than ¥9.2tn ($62bn) were spent in an attempt to prop up the yen, in the first such operation since 1998 (when the total size amounted to ¥4.2tn). Although the “limitless” amount of funds to conduct such interventions ($1.3tn) suggest that more yen-buying operations could come, analysts have questioned their effectiveness. Tokyo’s intervention might have been successful, at least for now, in putting a floor on the yen. However, outsized operations risk stoking market volatility. Even though Japanese companies seem stable and, because of the drop in the yen, cheap, as long as the contradiction between the Ministry of Finance’s effort to prop up the yen and the central bank’s easing policy is causing instability, a robust influx of foreign stock-buying, which would put a natural upward pressure on the yen, is unlikely.

The only way for the yen to really reverse its downward trend is for the monetary policies of the U.S. and Japan to start to converge again. Right now, they remain miles apart. Hence, given that any increase in rates have been ruled out until the rise in prices will be matched by increases in wages, the focus remains on the US Fed. All the BoJ can do is to wait, buying time in the hope that US rate hikes will peak soon.

III.What lies ahead?

If the bet on the US Fed turns out to be wrong, the BoJ will be forced to change course of action, with possible risks looming on the horizon. Some analysts predict that the Bank of Japan will adjust its yield cap on 10-year JGBs in 2023, perhaps by raising it. Yet, pegs are hard to move gracefully, and they often collapse in spectacular fashion. Given the BoJ’s enormous portfolio, any tweak that is perceived to be too fast or beyond expectations could cause rapid repercussions across markets. In a worst-case scenario, bond-market tumult could also cast doubt on the sustainability of Japan’s vast net government debts of about 170% of GDP. The opacity of cross-border financing flows involving the yen makes the global consequences of such an event unpredictable.

Hence, when the BoJ eventually (some say inevitably) changes its policy stance, it will need to come up with a basic plan beforehand, so that the market can expect what will be coming, avoiding the risk of misinterpretation.

The case of China

I.Economic outlook

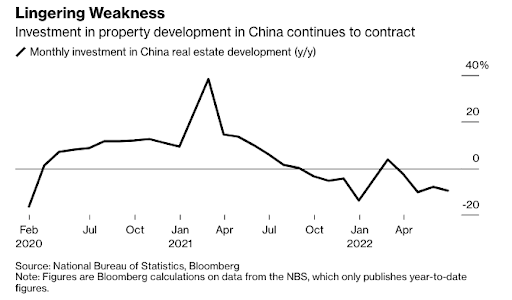

The economic growth showed a slow down to 1.3% quarter-on-quarter in Q1 2022 compared to the 1.5% of Q4 2021, this is partially due to the stringent measures still in place to cope with the pandemic that continue to cause lockdowns in major economic centers such as beijing and shanghai. These policies create a strong demand for new isolation facilities, new jobs in neighborhood centers, and delivery companies, which are communally less productive investments than other infrastructure. The automotive supply chain for example is experiencing severe problems, contributing to declining exports to western countries. Growth in investment is declining, a large part of this decline is due to theo in real estate investment. The introduction of new regulations (particularly the so-called three red lines, relating to financial ratios and caps on real estate lending by bank type), have decreased the liquidity conditions of large real estate companies, even causing some of them to fail.

The government did not stand by. In the past two months, more than ¥9.2tn ($62bn) were spent in an attempt to prop up the yen, in the first such operation since 1998 (when the total size amounted to ¥4.2tn). Although the “limitless” amount of funds to conduct such interventions ($1.3tn) suggest that more yen-buying operations could come, analysts have questioned their effectiveness. Tokyo’s intervention might have been successful, at least for now, in putting a floor on the yen. However, outsized operations risk stoking market volatility. Even though Japanese companies seem stable and, because of the drop in the yen, cheap, as long as the contradiction between the Ministry of Finance’s effort to prop up the yen and the central bank’s easing policy is causing instability, a robust influx of foreign stock-buying, which would put a natural upward pressure on the yen, is unlikely.

The only way for the yen to really reverse its downward trend is for the monetary policies of the U.S. and Japan to start to converge again. Right now, they remain miles apart. Hence, given that any increase in rates have been ruled out until the rise in prices will be matched by increases in wages, the focus remains on the US Fed. All the BoJ can do is to wait, buying time in the hope that US rate hikes will peak soon.

III.What lies ahead?

If the bet on the US Fed turns out to be wrong, the BoJ will be forced to change course of action, with possible risks looming on the horizon. Some analysts predict that the Bank of Japan will adjust its yield cap on 10-year JGBs in 2023, perhaps by raising it. Yet, pegs are hard to move gracefully, and they often collapse in spectacular fashion. Given the BoJ’s enormous portfolio, any tweak that is perceived to be too fast or beyond expectations could cause rapid repercussions across markets. In a worst-case scenario, bond-market tumult could also cast doubt on the sustainability of Japan’s vast net government debts of about 170% of GDP. The opacity of cross-border financing flows involving the yen makes the global consequences of such an event unpredictable.

Hence, when the BoJ eventually (some say inevitably) changes its policy stance, it will need to come up with a basic plan beforehand, so that the market can expect what will be coming, avoiding the risk of misinterpretation.

The case of China

I.Economic outlook

The economic growth showed a slow down to 1.3% quarter-on-quarter in Q1 2022 compared to the 1.5% of Q4 2021, this is partially due to the stringent measures still in place to cope with the pandemic that continue to cause lockdowns in major economic centers such as beijing and shanghai. These policies create a strong demand for new isolation facilities, new jobs in neighborhood centers, and delivery companies, which are communally less productive investments than other infrastructure. The automotive supply chain for example is experiencing severe problems, contributing to declining exports to western countries. Growth in investment is declining, a large part of this decline is due to theo in real estate investment. The introduction of new regulations (particularly the so-called three red lines, relating to financial ratios and caps on real estate lending by bank type), have decreased the liquidity conditions of large real estate companies, even causing some of them to fail.

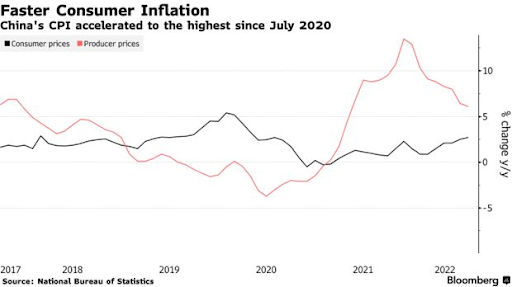

The impact of the war in Ukraine has been felt across global markets as neither Ukraine nor Russia are important economic partners (as opposed to vice versa). Energy and commodity prices have risen, however the latter has not been transferred to consumers, consumer price inflation has in fact remained constant and all due to the structure of consumption, with a large chunk of food and raw materials being produced in the country itself (minimizing imports). China's large grain reserves and restrictions on exports manage to keep the price of the latter at normal values, reducing the risk of shortages and coping with rising prices in global markets. However, lockdown-induced supply-side constraints on fresh food have begun to push CPI inflation upward, reaching 2.8 percent as of September 2022 (although core inflation remains at 0.6 percent). it is important to note that inflation is being kept in check by the discount mechanism in buying oil from Russia

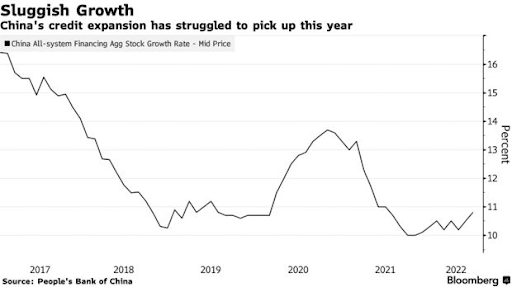

II. Monetary and fiscal policy

Monetary policy is assumed to be more dovish. The required reserve ratio and target interest rate have been cut twice since November 2021, and further cuts are assumed to follow. Credit risks have decreased although implicit vulnerabilities remain, credit events in the housing market have tightened credit conditions especially in the housing market, the phenomenon of shadow banking has been further reined in. This has driven a slight uptick in real interest rates, riling credit risk for smaller companies. With the portion of unsold properties has gained the highest level in fifteen years, many cities have introduced lump sums, economic stimulus for first-time buyers, or fiscal stimulus to do in order to revive the real estate sector and reduce the insolvency risks of large real estate companies (It is worth mentioning that China's real estate market is equivalent to twice the size of the U.S. real estate market).Corporate debt has stabilized at a very high level at about 155% of GDP, deleveraging therefore will continue.

The central bank said CPI will likely exceed 3% in some months during the second half of the year mainly due to seasonality and projected demand for imported goods. However China will likely achieve this target of keeping full-year inflation around 3% in 2022, thanks to measures taken to ensure grain and energy supply as well as prudent monetary policy.

Economists said while the People Bank of China (PBOC) warnings did signal a tightening in the monetary policy, there’s little scope for significant easing in coming months.

The PBOC will likely keep its overall reserve requirement ratio and policy rate unchanged instead favor targeted tools such as its re lending programs, or rely on policy banks to boost lending and support credit growth.

Qui Tai, chief macro analyst at Shenwan Hongyuan Group Co. Said that the PBOC’s pledge to “not over issue money” implies it thinks the current supply of liquidity is already sufficient, reducing the need to decrease the reserve ratio or to cut the policy rate for the rest of 2022.

The current economic situation in the US and Europe is one of the key factors to look at for China's macroeconomic policies, said Guo Shuquing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Maintaining the currency stability is a key responsibility for the central bank, and keeping stable inflation is crucial, he said.

II. Monetary and fiscal policy

Monetary policy is assumed to be more dovish. The required reserve ratio and target interest rate have been cut twice since November 2021, and further cuts are assumed to follow. Credit risks have decreased although implicit vulnerabilities remain, credit events in the housing market have tightened credit conditions especially in the housing market, the phenomenon of shadow banking has been further reined in. This has driven a slight uptick in real interest rates, riling credit risk for smaller companies. With the portion of unsold properties has gained the highest level in fifteen years, many cities have introduced lump sums, economic stimulus for first-time buyers, or fiscal stimulus to do in order to revive the real estate sector and reduce the insolvency risks of large real estate companies (It is worth mentioning that China's real estate market is equivalent to twice the size of the U.S. real estate market).Corporate debt has stabilized at a very high level at about 155% of GDP, deleveraging therefore will continue.

The central bank said CPI will likely exceed 3% in some months during the second half of the year mainly due to seasonality and projected demand for imported goods. However China will likely achieve this target of keeping full-year inflation around 3% in 2022, thanks to measures taken to ensure grain and energy supply as well as prudent monetary policy.

Economists said while the People Bank of China (PBOC) warnings did signal a tightening in the monetary policy, there’s little scope for significant easing in coming months.

The PBOC will likely keep its overall reserve requirement ratio and policy rate unchanged instead favor targeted tools such as its re lending programs, or rely on policy banks to boost lending and support credit growth.

Qui Tai, chief macro analyst at Shenwan Hongyuan Group Co. Said that the PBOC’s pledge to “not over issue money” implies it thinks the current supply of liquidity is already sufficient, reducing the need to decrease the reserve ratio or to cut the policy rate for the rest of 2022.

The current economic situation in the US and Europe is one of the key factors to look at for China's macroeconomic policies, said Guo Shuquing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory Commission. Maintaining the currency stability is a key responsibility for the central bank, and keeping stable inflation is crucial, he said.

Monetary policy easing is furtherly complicated by the increase in interest rates in the US and elsewhere, acknowledging that the hawkish monetary policies globally, the PBOC said that its unchanged policy rates helped to stabilize both internal and external balance against widespread hikes by major global central banks. Fiscal policy will provide support in the form of cuts in taxes, charging and spending of reserve funds. In addition, the submission of ad-hoc dividends from state-owned companies in the financial sector, equivalent to 0.8 percent of GDP will be partially spent on infrastructure investment. Recent requirements for local government investment vehicles to secure budget to carry out infrastructure projects helps contain contingent liabilities, in fact, to best mobilize in the push for infrastructure, they will have easier access to funding.

Conclusions

Although we are assisting to an increasingly inflationary global outlook that sparked a streak of tightening unprecedented in recent monetary history, the countries we focused on are telling a completely different story. If on the one hand western countries are suffering from a particularly adverse situation, originating from supply chain disruptions and increasing costs of energy and commodities, the economic scenario that we observe in the Asian landscape is substantially different.

Hence, the relatively low inflation environment in China is linked to the opportunity to buy fuels at significantly discounted prices from Russia (that is now directing a large share of its exports to China and India) and the large strategic reserves of grains that resulted in low levels in CPI and Core inflation. Moreover, the problems linked to the real estate crises experienced last year with the notorious case Evergrande, brought a significant amount of concern on the monetary and fiscal policies that the country should adopt. In order to spur the purchase of properties and stimulate the economy , the government is implementing significant measures varying from lump sums and aids to real estate development companies in order for them to face the losses linked to unsold buildings.

The situation in Japan might be trickier to interpret, in the sense that, although, due to structural factors in its economy, it shows an inflation rate that fluctuates at enviably low levels compared to the Western world, those levels are still extremely high from the Japanese perspective, if compared to recent decades. Mostly driven by higher energy costs and import appreciation (due to a weaker currency), monetary policy is doing all it can to make it entrenched in the economy, as a way to escape the stagnation that trapped the country in a situation of low growth for over 25 years. As a result, the BoJ is not only avoiding tightening in response to the higher inflation, but it is also continuing to support the economy with its extremely expansionary measures, in a desperate attempt to exploit this situation to its advantage. As we have seen, this approach comes with some costs; costs that possibly represent significant risks for the future.

Sources

By Federico Tita, Federico Pepe, Roberto Fani and Giorgio Gusella

Conclusions

Although we are assisting to an increasingly inflationary global outlook that sparked a streak of tightening unprecedented in recent monetary history, the countries we focused on are telling a completely different story. If on the one hand western countries are suffering from a particularly adverse situation, originating from supply chain disruptions and increasing costs of energy and commodities, the economic scenario that we observe in the Asian landscape is substantially different.

Hence, the relatively low inflation environment in China is linked to the opportunity to buy fuels at significantly discounted prices from Russia (that is now directing a large share of its exports to China and India) and the large strategic reserves of grains that resulted in low levels in CPI and Core inflation. Moreover, the problems linked to the real estate crises experienced last year with the notorious case Evergrande, brought a significant amount of concern on the monetary and fiscal policies that the country should adopt. In order to spur the purchase of properties and stimulate the economy , the government is implementing significant measures varying from lump sums and aids to real estate development companies in order for them to face the losses linked to unsold buildings.

The situation in Japan might be trickier to interpret, in the sense that, although, due to structural factors in its economy, it shows an inflation rate that fluctuates at enviably low levels compared to the Western world, those levels are still extremely high from the Japanese perspective, if compared to recent decades. Mostly driven by higher energy costs and import appreciation (due to a weaker currency), monetary policy is doing all it can to make it entrenched in the economy, as a way to escape the stagnation that trapped the country in a situation of low growth for over 25 years. As a result, the BoJ is not only avoiding tightening in response to the higher inflation, but it is also continuing to support the economy with its extremely expansionary measures, in a desperate attempt to exploit this situation to its advantage. As we have seen, this approach comes with some costs; costs that possibly represent significant risks for the future.

Sources

- The Economist

- FT

- WSJ

- Bloomberg

- CNBC

- China Macro Economy

By Federico Tita, Federico Pepe, Roberto Fani and Giorgio Gusella