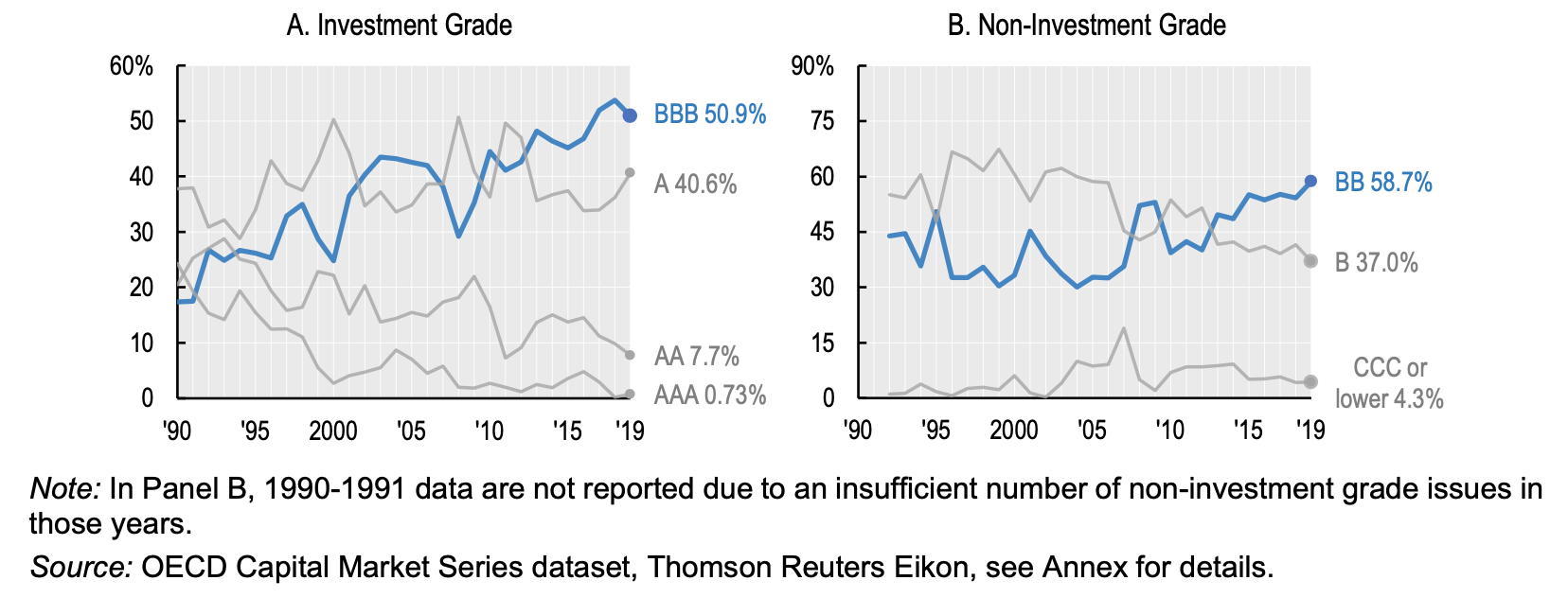

The low interest rates that the Federal Reserve implemented to revive the economy from the depths of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis contributed to solving the United States’ grave short-term ails but triggered the explosive growth of a problem that is only now coming back to haunt us – a $13.5 trillion global corporate debt binge. A study conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) on emerging risks in the corporate bond market, concluded that this massive pool of corporate debt suffers from lower overall credit quality, higher payback requirements, longer maturities, and inferior covenants. Specifically, in the post-crisis low rate environment, the percentage of BBB rated bonds as a proportion of total investment-grade bonds has risen substantially – from 38.9% in 2000-2017 to 51% in 2019.

Composition of Issuance in Investment and Non-Investment Grade Categories

Part of the growth in BBB rated bonds may be attributed to credit rating agencies’ increased leniency when rating debt investment-grade. This growth may also be due to increasing demand from institutional investors searching for opportunities with higher potential returns while still remaining compliant with their mandates to focus on investment-grade credit. Aramonte and Eren (2019) report that “since the financial crisis, the portion of BBB bonds in the portfolios of investment-grade corporate bond mutual funds in the U.S. steadily grew from around 20% in 2010 to about 45% in 2018” (OECD 13). In their hunt for yield, investors have also agreed to weaker covenants in order to experience increased potential returns, another indication of investors’ growing appetite for risk. And that is not all. Within the corporate debt market lurks another threat to global economic stability – zombie companies – a classification reserved for corporations that do not earn enough income to service their interest payments and survive merely by refinancing their debt at low rates. These firms, which Morgan Stanley’s Chief Global Strategist Ruchir Sharma believes represent 1 in 6 publicly traded U.S. companies, have been kept alive by low interest rates and bull market conditions. In the words of Warren Buffet, “only when the tide goes out do you discover who’s been swimming naked” – and if recent market conditions offer any guidance, investors are expecting a full moon tide and many skinny-dippers.

The corporate debt binge described above is not a recently-discovered phenomenon. Bankers, economists, lawyers, policy makers and professionals across a wide array of industries have been observing the development of this corner of the fixed-income market for years. For example, in November of 2019, the Federal Reserve stated that “in an economic downturn, widespread downgrades of bonds to speculative-grade ratings could lead investors to sell the downgraded bonds rapidly, increasing market illiquidity and downward price pressures”. Those analyzing this phenomenon were most likely reassured by the lack of a trigger that could set off a wave of corporate defaults.

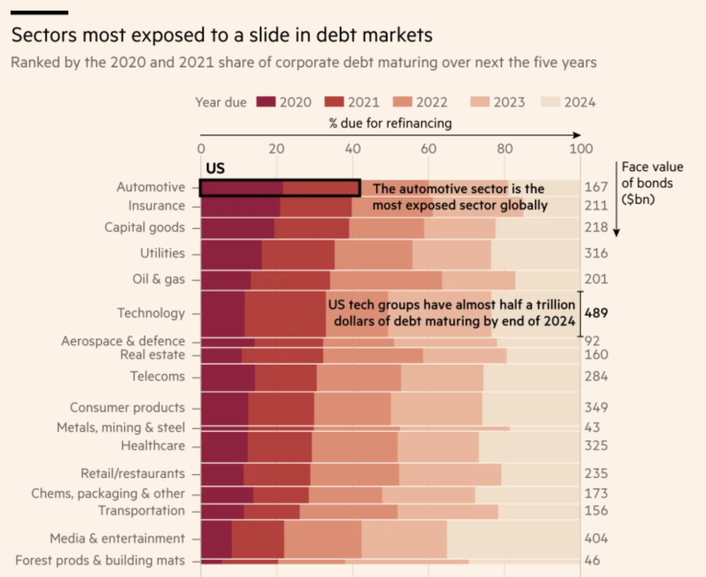

Enter COVID-19. The virus has now reached every continent on the planet and has forced many millions of individuals into a mix of government-imposed quarantines and social distancing to “flatten the curve” and minimize the strain placed on overburdened healthcare systems. Although desperately needed, an unfortunate consequence of these safety measures has been a steep drop off in demand for the goods and services produced by companies in sectors such as retail, hospitality, transport, oil and gas and many others. This drop off has all but eliminated the revenue of companies in these industries (see the below chart from the Financial Times for the sectors with the heaviest debt loads – note that many have been negatively impacted by the COVID-19 shutdown). The energy sector has been hit particularly hard as demand for oil has collapsed (due to grounded flights caused by COVID-19) while a price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia has resulted in a surge in the supply of crude oil. These combined deflationary shocks have sent oil prices tumbling from close to $65 a barrel in January to as low as $20 a barrel on Monday.

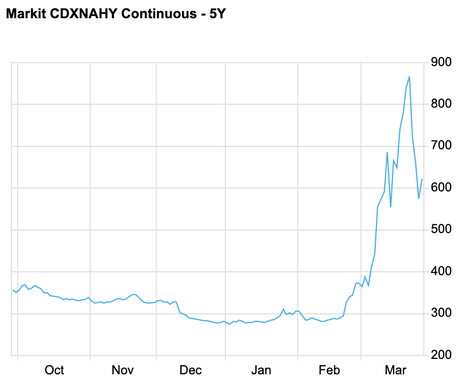

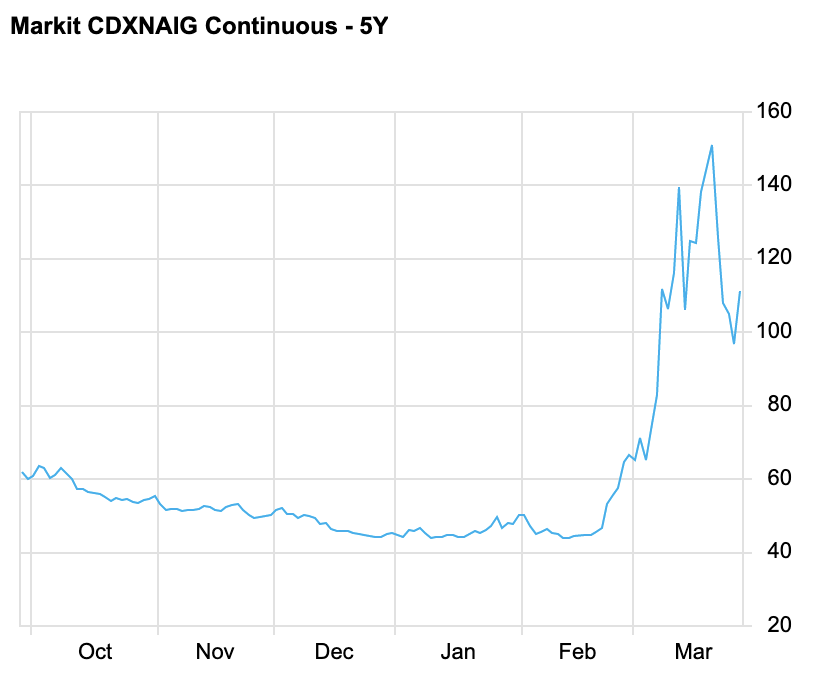

Many companies including Hilton, Anheuser Busch-Inbev, Carnival Cruises, GM, and Ford have drawn down their revolvers – a source of funding reserved for emergency situations – due to the lack of access to other sources of capital for all but the most investment-grade names. The Financial Times notes that over the past three weeks, more than 130 companies in Europe and the Americas have drawn at least $124 billion from their lenders at a rate faster than ever seen before. A team at the Economist recently conducted a highly-relevant “cash-crunch-stress-test” of close to 3,000 non-financial firms operating outside of China. Assuming sales fall by two-thirds and that these companies are still obligated to pay operating costs, the team found that within three months 13% of these firms would exhaust all cash on hand and be forced to borrow, retrench, or default. If economic activity were to remain at this level for six months, 25% of all firms in their study would run out of cash. Moody’s estimates, released last Friday, are not pretty either. The credit rating agency believes that “a sharp but short-lived downturn would increase the default rate among junk-rated borrowers to 6.8%. [While] a recession on par with the previous one would mean a 16.1% default rate in a year”. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Professor Ed Altman, the father of the Z-score, expressed concern for a growing number of high-yield defaults: “by the end of Q2 of this year if not Q3… we expect to see $150 billion of defaults from high-yield debt bankruptcies”. Further he remarks that his models show that recovery rates on corporate debt will drop to below 30% for corporate bonds in the next six to nine months. The markets seem to confirm these ominous forecasts. Many companies in the investment-grade market have been trading at high-yield levels while many in the high-yield market have been trading at distressed levels (see the below chart from Bloomberg for IG and HY yields as of last Thursday).

Many companies including Hilton, Anheuser Busch-Inbev, Carnival Cruises, GM, and Ford have drawn down their revolvers – a source of funding reserved for emergency situations – due to the lack of access to other sources of capital for all but the most investment-grade names. The Financial Times notes that over the past three weeks, more than 130 companies in Europe and the Americas have drawn at least $124 billion from their lenders at a rate faster than ever seen before. A team at the Economist recently conducted a highly-relevant “cash-crunch-stress-test” of close to 3,000 non-financial firms operating outside of China. Assuming sales fall by two-thirds and that these companies are still obligated to pay operating costs, the team found that within three months 13% of these firms would exhaust all cash on hand and be forced to borrow, retrench, or default. If economic activity were to remain at this level for six months, 25% of all firms in their study would run out of cash. Moody’s estimates, released last Friday, are not pretty either. The credit rating agency believes that “a sharp but short-lived downturn would increase the default rate among junk-rated borrowers to 6.8%. [While] a recession on par with the previous one would mean a 16.1% default rate in a year”. In a recent interview with Bloomberg, Professor Ed Altman, the father of the Z-score, expressed concern for a growing number of high-yield defaults: “by the end of Q2 of this year if not Q3… we expect to see $150 billion of defaults from high-yield debt bankruptcies”. Further he remarks that his models show that recovery rates on corporate debt will drop to below 30% for corporate bonds in the next six to nine months. The markets seem to confirm these ominous forecasts. Many companies in the investment-grade market have been trading at high-yield levels while many in the high-yield market have been trading at distressed levels (see the below chart from Bloomberg for IG and HY yields as of last Thursday).

Source: Markit, FactSet – March 30th, 2020

In yet another confirmation of the stress in credit markets, the spreads on the CDX IG and CDX HY indexes (which represent the annual cost to insure $10 million of IG and HY bonds against default for five years) have blown out as can be seen in the charts above.

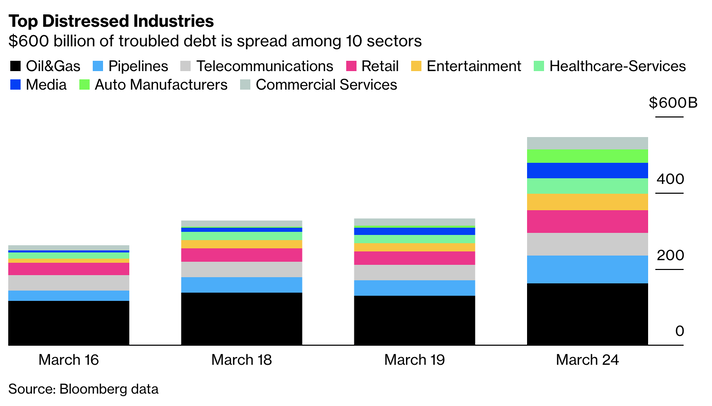

The stock of high-yield corporate bonds now totals $1.5 trillion, far higher than the $700 billion in 2007. Even more alarming, over the past week alone, the amount of distressed U.S. corporate debt has quadrupled to roughly $934 billion, the highest level since April 2009. The chart below illustrates a breakdown of $600 billion of this debt. Some of these sectors are especially sensitive to shocks from COVID-19.

The stock of high-yield corporate bonds now totals $1.5 trillion, far higher than the $700 billion in 2007. Even more alarming, over the past week alone, the amount of distressed U.S. corporate debt has quadrupled to roughly $934 billion, the highest level since April 2009. The chart below illustrates a breakdown of $600 billion of this debt. Some of these sectors are especially sensitive to shocks from COVID-19.

We are no doubt entering what Moody’s claims will be a “severe and extensive credit shock across many sectors, regions and markets”. As of last Thursday, S&P and Moody’s downgraded 280 and 180 firms respectively, downgrades outpaced upgrades by three to one. As alluded to earlier in the article, investors are particularly concerned about one specific segment of the corporate bond market – BBB rated bonds. This rating serves as the demarcation between which tranches of debt are considered investment-grade and which are considered high-yield, an important distinction for institutional investors bound by mandates to invest in investment-grade credit. Companies such as Occidental, that were rated investment-grade but were downgraded to high-yield are known as fallen angels. As recently as this past week, Ford joined the list of major fallen angels as roughly $36 billion of its debt was downgraded to high-yield. Such downgrades not only raise the cost of debt for future borrowing but also prompt a round of forced selling by institutional investors that are bound by the aforementioned mandates. Moreover, the $1.2 trillion high-yield corporate bond market will no doubt find it challenging to digest such overwhelming new supply from such large issuances (i.e. those of Ford and Occidental) making an already illiquid market even more illiquid and further depressing prices. Other notable 2020 U.S. fallen angels include Kraft Heinz and Macy’s. Companies such as AT&T and Anheuser Busch-Inbev have been actively taking measures to avoid rating downgrades by reducing their debt loads.

Earlier last week the Federal Reserve took aggressive measures to backstop the investment-grade corporate bond market by launching the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). The PMCCF is a special purpose vehicle that will allow the Federal Reserve to lend directly to investment-grade businesses. Meanwhile, the SMCCF is a special purpose vehicle that will allow the Federal Reserve to buy U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds and bond ETFs in the secondary market. The first initiative will ensure that companies have enough capital to continue their operations with limited layoffs, while the second initiative will inject liquidity into the investment-grade market and encourage banks to continue to lend. Last Friday, Congress passed the CARES Act – a $2 trillion aid package meant to help support the U.S. in its physical and economic fight against COVID-19. Roughly $500 billion of these funds will go towards backstopping the Federal Reserve’s PMCCF and SMCCF. The Federal Reserve will most likely not rescue the high-yield corporate bond market because it does not want to bear such significant default risk. However the recently announced PMCCF and SMCCF will have beneficial knock-on effects on the high-yield market by potentially reducing the amount of fallen angels and the resulting stress they inflict on the speculative-grade market.

The actions taken by the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Department of the Treasury reassured the market for investment-grade corporate debt. Some of the world’s highest-rated companies including – Nike, Walt Disney, McDonald’s and Pepsi – have issued over $73 billion in debt last week alone. The Fed’s actions may also have positively impacted the high-yield market. On Monday Yum Brands issued the first speculative-grade bond since March 4th. While borrowing costs have undoubtedly risen, these companies have jumped at the opportunity to shore up their balance sheets in anticipation of the storm ahead.

Some may argue that the Federal Reserve should intervene in the high-yield corporate debt market. However, the Fed’s support for investment-grade bonds is in and of itself an entirely new endeavor that was not even pursued to combat the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The Fed, unlike the ECB which purchases bonds due in as long as 30 years, is not comfortable with assuming large amounts of default risk nor should it have to. It is not the job of the Fed to protect companies that are irresponsibly overleveraged. If the Fed were to backstop the high-yield market, their actions would not only undermine credit ratings but also further propagate the debt binge that gave rise to this situation in the first place – much like the low rates following the previous recession. There is no doubt that some businesses, such as the zombie companies defined at the beginning of this article, might inevitably be forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and restructure. However, the corporate debt issue is one that must be faced head on through deleveraging, not kicked further down the road by a Fed backstop that would encourage additional moral hazard. Some journalists have also suggested that credit rating agencies should momentarily stop rating corporate debt. However, it is the job of rating agencies to provide an objective assessment of risk no matter the economic climate – and as of now, these agencies wield a lot of power in that by downgrading a company from investment-grade to high-yield they are able to help the Fed direct its rescue efforts. A potentially feasible path to limit the strain on the high-yield markets and encourage more new issues could be for institutional investors to revise their mandates so that they are able to invest in high-quality names that have recently slipped into the high-yield market. This could help avoid the previously discussed fire sales and help alleviate some of the potential stress on the high-yield markets.

With all of the uncertainty surrounding the next couple of months one thing can be certain. The events described above, and those that will follow as a result, will undoubtedly have the entire finance community on edge as they watch from their WFH setups.

Richard Jové

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

We are no doubt entering what Moody’s claims will be a “severe and extensive credit shock across many sectors, regions and markets”. As of last Thursday, S&P and Moody’s downgraded 280 and 180 firms respectively, downgrades outpaced upgrades by three to one. As alluded to earlier in the article, investors are particularly concerned about one specific segment of the corporate bond market – BBB rated bonds. This rating serves as the demarcation between which tranches of debt are considered investment-grade and which are considered high-yield, an important distinction for institutional investors bound by mandates to invest in investment-grade credit. Companies such as Occidental, that were rated investment-grade but were downgraded to high-yield are known as fallen angels. As recently as this past week, Ford joined the list of major fallen angels as roughly $36 billion of its debt was downgraded to high-yield. Such downgrades not only raise the cost of debt for future borrowing but also prompt a round of forced selling by institutional investors that are bound by the aforementioned mandates. Moreover, the $1.2 trillion high-yield corporate bond market will no doubt find it challenging to digest such overwhelming new supply from such large issuances (i.e. those of Ford and Occidental) making an already illiquid market even more illiquid and further depressing prices. Other notable 2020 U.S. fallen angels include Kraft Heinz and Macy’s. Companies such as AT&T and Anheuser Busch-Inbev have been actively taking measures to avoid rating downgrades by reducing their debt loads.

Earlier last week the Federal Reserve took aggressive measures to backstop the investment-grade corporate bond market by launching the Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility (PMCCF) and the Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility (SMCCF). The PMCCF is a special purpose vehicle that will allow the Federal Reserve to lend directly to investment-grade businesses. Meanwhile, the SMCCF is a special purpose vehicle that will allow the Federal Reserve to buy U.S. investment-grade corporate bonds and bond ETFs in the secondary market. The first initiative will ensure that companies have enough capital to continue their operations with limited layoffs, while the second initiative will inject liquidity into the investment-grade market and encourage banks to continue to lend. Last Friday, Congress passed the CARES Act – a $2 trillion aid package meant to help support the U.S. in its physical and economic fight against COVID-19. Roughly $500 billion of these funds will go towards backstopping the Federal Reserve’s PMCCF and SMCCF. The Federal Reserve will most likely not rescue the high-yield corporate bond market because it does not want to bear such significant default risk. However the recently announced PMCCF and SMCCF will have beneficial knock-on effects on the high-yield market by potentially reducing the amount of fallen angels and the resulting stress they inflict on the speculative-grade market.

The actions taken by the Federal Reserve and the U.S. Department of the Treasury reassured the market for investment-grade corporate debt. Some of the world’s highest-rated companies including – Nike, Walt Disney, McDonald’s and Pepsi – have issued over $73 billion in debt last week alone. The Fed’s actions may also have positively impacted the high-yield market. On Monday Yum Brands issued the first speculative-grade bond since March 4th. While borrowing costs have undoubtedly risen, these companies have jumped at the opportunity to shore up their balance sheets in anticipation of the storm ahead.

Some may argue that the Federal Reserve should intervene in the high-yield corporate debt market. However, the Fed’s support for investment-grade bonds is in and of itself an entirely new endeavor that was not even pursued to combat the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. The Fed, unlike the ECB which purchases bonds due in as long as 30 years, is not comfortable with assuming large amounts of default risk nor should it have to. It is not the job of the Fed to protect companies that are irresponsibly overleveraged. If the Fed were to backstop the high-yield market, their actions would not only undermine credit ratings but also further propagate the debt binge that gave rise to this situation in the first place – much like the low rates following the previous recession. There is no doubt that some businesses, such as the zombie companies defined at the beginning of this article, might inevitably be forced to file for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection and restructure. However, the corporate debt issue is one that must be faced head on through deleveraging, not kicked further down the road by a Fed backstop that would encourage additional moral hazard. Some journalists have also suggested that credit rating agencies should momentarily stop rating corporate debt. However, it is the job of rating agencies to provide an objective assessment of risk no matter the economic climate – and as of now, these agencies wield a lot of power in that by downgrading a company from investment-grade to high-yield they are able to help the Fed direct its rescue efforts. A potentially feasible path to limit the strain on the high-yield markets and encourage more new issues could be for institutional investors to revise their mandates so that they are able to invest in high-quality names that have recently slipped into the high-yield market. This could help avoid the previously discussed fire sales and help alleviate some of the potential stress on the high-yield markets.

With all of the uncertainty surrounding the next couple of months one thing can be certain. The events described above, and those that will follow as a result, will undoubtedly have the entire finance community on edge as they watch from their WFH setups.

Richard Jové

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.