One half of the world coal supply is burned by China each year.

Over 25% of the world’s climate pollution originates in China.

China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide.

Beijing has invested heavily in coal plants in developing nations as part of Mr Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative. Its carbon emissions rose in 2017 and in the first part of this year owing to economic growth, having been flat from 2014-16. The country’s official target for carbon reduction — it has pledged to reduce emissions after 2030 — is not compatible with the cuts needed to meet the Paris pledge to limit global warming to well below 2C.

This means that this nation is at the centre of the discussion about carbon emissions and their economic footprint. But while passively accepting the situation before, the country is now spreading the feeling that it will proactively participate.

When did this evolution process started?

In past, many Chinese believed that climate change was a lie made up by developed countries to contain the growth of developing ones, especially China. Even after scientific probations the idea was that country had a “common but differentiated responsibility”.

A critical moment came in 2008, when on the Spring Festival’s eve, freezing temperatures and heavy rain hit the South of the country, paralyzing but oxymoronically awakening people of China. Thanks to the wide reach of the internet, every extreme-weather event since has caught massive attention.

Climate change and air pollution are different issues, but air pollution is produced by the same sources that emit carbon dioxide, which provokes climate change: heating, power generation, industrial activity and cars. Controlling pollution can also mean cutting emissions. And looking at the current situation a change is needed.

After this realization and higher awareness, what are the actions that the government put in place to address the issue? During recent trade summits the Chinese government temporally closed some industrial buildings to reduce pollution, but without a real impact on the problem. Moreover, in 2009 China announced a cut in carbon emissions by 40-45% relative to GDP growth by 2020, compared with 2005 levels. Then, in 2014, it said it wanted carbon-emission levels to increase and peak around 2030, year after which emission should reduce. Now the government is trying to move this date forward, meaning that they want to postpone the date of reduction of emissions, thus having the possibility to exploit more years of high emissions.

A symptom of this renewed and positive attention to climate change issues could be represented by the evolution of the industry of renewables.

According to Moody’s, emerging markets will overcome developed ones in terms of renewable energy installed, mainly solar and wind.

In the ten years before 2016, the amount of solar power generated in the world has risen by 50 per cent, while wind has increased by 22 per cent, according to BP’s annual review of world energy. Developed economies have led the development of renewable power, but much of the recent momentum has come from developing nations, China and India in particular.

The increase comes from different reasons. First of all, the pre-mentioned increasing awareness of the need to shit to clean energy provision. Second, the pressures deriving from Paris accords, on which we will focus more later. The third reason is the decrease in cost of wind and solar technologies, which obviously makes the sector more attractive for different industries. This reduction is led by two major factors: technology expansion and oversupply.

Last year, China added 50 gigawatts of solar power capacity, more than it added for coal, gas and nuclear power capacity put together. It also added 15.6GW of wind capacity, reaching 10% more.

There are, however, signs that the momentum could be about to slow down. In particular, the June policy in Beijing that cut incentives for solar panels.

Not only the industrial world is influenced by this growing awareness. As a matter of fact, the financial sector has seen its developments, which however are threatened to slow down as for the industrial sector.

China is quietly introducing green financing as a source of domestic lending, thanks to the renewed consciousness of citizens and to the tightening of other sources. The diversification of green financing has coincided with a rise in international investors’ interest. The Luxembourg Stock Exchange offers translated information on a selection of green bonds trading in Shanghai, while Hong Kong is trying to attract mainland issuers to its market.

So, every cloud has a silver lining, we would be pushed to say. But it’s not precisely like that.

Chinese standards for green bonds include a tolerance for clean coal projects, while coal is excluded elsewhere. China also allows up to half the proceeds to be used to pay down previous loans, whereas Climate Bond Initiative standards require almost all the funds to be allocated to the underlying project. In 2017, China issued $22.9bn in green bonds that align with CBI standards, and another $14.2bn that did not. China’s green bonds are still dominated by banks to a greater extent than in other countries. So, despite the international interest, China’s share of the world’s total of green bonds that meet standards set by the CBI dropped to 12 per cent in the first half of this year, from 15 per cent in 2017 and almost 40 per cent in 2016.

Despite this “black sides”, new ideas for projects include green loans, creation of green commercial banks and green insurance.

However, there are concerns for the lacking action about climate change which are amplified by the fact that the world’s biggest energy companies are spending only a fraction of their investment budgets on low-carbon projects, even as the oil and gas industry comes under fire for its contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions. Staying in China, recriminated companies are China’s Cnooc and Sinopec. BP’s chief executive Bob Dudley said last month they could supply about a third of the energy mix by about 2040. But what about the remaining two-thirds of demand?

Big producers have warned that forcing companies to pull back spending on traditional oil and gas projects in favour low-carbon investments or flexible US shale production will only threaten energy security and create supply shortages.

But what is actual pollution level?

Thick smog blanketed northern China lately, a reversal of the blue skies seen last winter as authorities reduced environmental targets to boost economic growth. Levels of particulate matter of 2.5 microns (PM2.5), a standard for measuring air pollution, peaked above 12 times the World Health Organization guidelines for outdoor air quality.

The cause is thought to be the pollution from the heating, not led away from the unfortunately missing wind.

The looser environmental standards are part of a host of measures, including an infrastructure stimulus and tax cuts, aimed at restoring confidence in the country’s slowing economy. Rather than place hard caps on coal use and steel production, authorities this year have instead mandated that PM2.5 levels must fall 3 per cent rather than the previously proposed 5 per cent target.

China’s pollution obsession spawns a global consumer industry Levels of PM2.5 fell 33 per cent across the 28 cities affected in the last quarter of 2017 while Beijing levels fell even more significantly, by 54 per cent, according to Greenpeace. However, the cuts came at a cost for small companies and state-owned enterprises, as authorities banned construction and shut down workshops and factories around Beijing and Shanghai. Meanwhile, steel producers in four large production cities were ordered to slash steel production in half during the autumn and winter months while reducing the use of coking coal by nearly a third.

Over 25% of the world’s climate pollution originates in China.

China is the world’s largest emitter of carbon dioxide.

Beijing has invested heavily in coal plants in developing nations as part of Mr Xi’s signature Belt and Road Initiative. Its carbon emissions rose in 2017 and in the first part of this year owing to economic growth, having been flat from 2014-16. The country’s official target for carbon reduction — it has pledged to reduce emissions after 2030 — is not compatible with the cuts needed to meet the Paris pledge to limit global warming to well below 2C.

This means that this nation is at the centre of the discussion about carbon emissions and their economic footprint. But while passively accepting the situation before, the country is now spreading the feeling that it will proactively participate.

When did this evolution process started?

In past, many Chinese believed that climate change was a lie made up by developed countries to contain the growth of developing ones, especially China. Even after scientific probations the idea was that country had a “common but differentiated responsibility”.

A critical moment came in 2008, when on the Spring Festival’s eve, freezing temperatures and heavy rain hit the South of the country, paralyzing but oxymoronically awakening people of China. Thanks to the wide reach of the internet, every extreme-weather event since has caught massive attention.

Climate change and air pollution are different issues, but air pollution is produced by the same sources that emit carbon dioxide, which provokes climate change: heating, power generation, industrial activity and cars. Controlling pollution can also mean cutting emissions. And looking at the current situation a change is needed.

After this realization and higher awareness, what are the actions that the government put in place to address the issue? During recent trade summits the Chinese government temporally closed some industrial buildings to reduce pollution, but without a real impact on the problem. Moreover, in 2009 China announced a cut in carbon emissions by 40-45% relative to GDP growth by 2020, compared with 2005 levels. Then, in 2014, it said it wanted carbon-emission levels to increase and peak around 2030, year after which emission should reduce. Now the government is trying to move this date forward, meaning that they want to postpone the date of reduction of emissions, thus having the possibility to exploit more years of high emissions.

A symptom of this renewed and positive attention to climate change issues could be represented by the evolution of the industry of renewables.

According to Moody’s, emerging markets will overcome developed ones in terms of renewable energy installed, mainly solar and wind.

In the ten years before 2016, the amount of solar power generated in the world has risen by 50 per cent, while wind has increased by 22 per cent, according to BP’s annual review of world energy. Developed economies have led the development of renewable power, but much of the recent momentum has come from developing nations, China and India in particular.

The increase comes from different reasons. First of all, the pre-mentioned increasing awareness of the need to shit to clean energy provision. Second, the pressures deriving from Paris accords, on which we will focus more later. The third reason is the decrease in cost of wind and solar technologies, which obviously makes the sector more attractive for different industries. This reduction is led by two major factors: technology expansion and oversupply.

Last year, China added 50 gigawatts of solar power capacity, more than it added for coal, gas and nuclear power capacity put together. It also added 15.6GW of wind capacity, reaching 10% more.

There are, however, signs that the momentum could be about to slow down. In particular, the June policy in Beijing that cut incentives for solar panels.

Not only the industrial world is influenced by this growing awareness. As a matter of fact, the financial sector has seen its developments, which however are threatened to slow down as for the industrial sector.

China is quietly introducing green financing as a source of domestic lending, thanks to the renewed consciousness of citizens and to the tightening of other sources. The diversification of green financing has coincided with a rise in international investors’ interest. The Luxembourg Stock Exchange offers translated information on a selection of green bonds trading in Shanghai, while Hong Kong is trying to attract mainland issuers to its market.

So, every cloud has a silver lining, we would be pushed to say. But it’s not precisely like that.

Chinese standards for green bonds include a tolerance for clean coal projects, while coal is excluded elsewhere. China also allows up to half the proceeds to be used to pay down previous loans, whereas Climate Bond Initiative standards require almost all the funds to be allocated to the underlying project. In 2017, China issued $22.9bn in green bonds that align with CBI standards, and another $14.2bn that did not. China’s green bonds are still dominated by banks to a greater extent than in other countries. So, despite the international interest, China’s share of the world’s total of green bonds that meet standards set by the CBI dropped to 12 per cent in the first half of this year, from 15 per cent in 2017 and almost 40 per cent in 2016.

Despite this “black sides”, new ideas for projects include green loans, creation of green commercial banks and green insurance.

However, there are concerns for the lacking action about climate change which are amplified by the fact that the world’s biggest energy companies are spending only a fraction of their investment budgets on low-carbon projects, even as the oil and gas industry comes under fire for its contributions to global greenhouse gas emissions. Staying in China, recriminated companies are China’s Cnooc and Sinopec. BP’s chief executive Bob Dudley said last month they could supply about a third of the energy mix by about 2040. But what about the remaining two-thirds of demand?

Big producers have warned that forcing companies to pull back spending on traditional oil and gas projects in favour low-carbon investments or flexible US shale production will only threaten energy security and create supply shortages.

But what is actual pollution level?

Thick smog blanketed northern China lately, a reversal of the blue skies seen last winter as authorities reduced environmental targets to boost economic growth. Levels of particulate matter of 2.5 microns (PM2.5), a standard for measuring air pollution, peaked above 12 times the World Health Organization guidelines for outdoor air quality.

The cause is thought to be the pollution from the heating, not led away from the unfortunately missing wind.

The looser environmental standards are part of a host of measures, including an infrastructure stimulus and tax cuts, aimed at restoring confidence in the country’s slowing economy. Rather than place hard caps on coal use and steel production, authorities this year have instead mandated that PM2.5 levels must fall 3 per cent rather than the previously proposed 5 per cent target.

China’s pollution obsession spawns a global consumer industry Levels of PM2.5 fell 33 per cent across the 28 cities affected in the last quarter of 2017 while Beijing levels fell even more significantly, by 54 per cent, according to Greenpeace. However, the cuts came at a cost for small companies and state-owned enterprises, as authorities banned construction and shut down workshops and factories around Beijing and Shanghai. Meanwhile, steel producers in four large production cities were ordered to slash steel production in half during the autumn and winter months while reducing the use of coking coal by nearly a third.

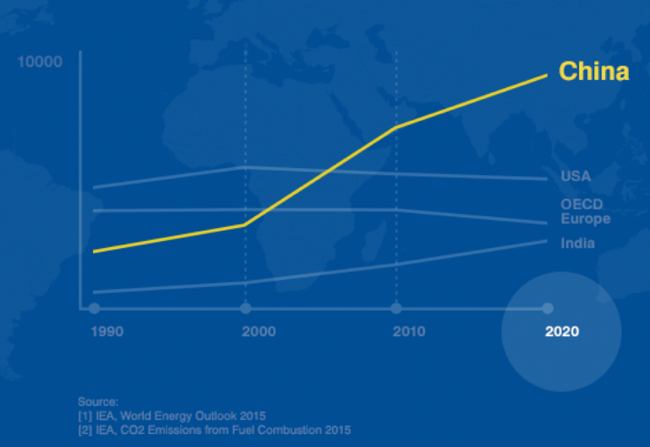

Projected CO2 Emissions under CURRENT POLICIES

Source: IEA, World Energy Outlook 2015; IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2015

Source: IEA, World Energy Outlook 2015; IEA, CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion 2015

The importance of china, however, is not to be put into discussion, but on the contrary it raised momentum since Trump left the climate change accord.

The last accord was decided three years ago in Paris and the next will take place in Polonia.

China is expected to be the leader and for the first time, it is hosting many of the preparatory meetings that are crucial for setting the direction of the COP24 summit. The role reversal is all the more surprising because Beijing had, for many years, shunned a leadership role in climate talks but now Beijing’s influence could steer the Paris agreement towards a slower pace of climate action. In previous negotiations, China’s influence was counterbalanced by the US, that would draw Beijing closer to its own positions. However, the authority of the EU, which is seeking to take up the leadership, is seen as being weaker. If the US and China could agree, usually everybody would fall into place behind them but now there’s no one who can pull back on China.

Under the Paris accord, more than 190 nations pledged to work together to limit global warming to well below 2C, but it is up to each country to set its own targets. China wants developing countries to have more relaxed reporting standards than developed ones, because they may lack the capacity for complex emissions modelling. The US and EU are among those who want all countries to have the same rules for emissions reporting, with a limited degree of flexibility for the least developed countries. Beijing has also insisted that it should be treated as a developing nation, despite being on purchasing power parity the world’s largest economy.

“The big question is which China will turn up? We know the leadership in Beijing supports the Paris agreement. It needs to help deliver a strong set of rules and redirect finance away from coal. We used to be more passive participants, and now we’re more proactive” (Xie Zhenhua, China’s lead climate negotiator).

So, what is next?

Recent efforts to cut overcapacity are the starting-point. It is concentrated in high-emission industries such as steel and coal, whose capacity the government wants to control. Industrial businesses will feel the force of strict carbon-emissions regulations. This links progress to economic reforms and efforts to improve regional industrial structures.

China’s emphasis must move from mitigation of climate change to adaptation to it. That involves upgrading infrastructure, changing lifestyles and further raising public consciousness. In the long run, as China’s industries shift from manufacturing to services, social resistance to the economic effects of climate-change action will decrease.

Giulia Galli

The last accord was decided three years ago in Paris and the next will take place in Polonia.

China is expected to be the leader and for the first time, it is hosting many of the preparatory meetings that are crucial for setting the direction of the COP24 summit. The role reversal is all the more surprising because Beijing had, for many years, shunned a leadership role in climate talks but now Beijing’s influence could steer the Paris agreement towards a slower pace of climate action. In previous negotiations, China’s influence was counterbalanced by the US, that would draw Beijing closer to its own positions. However, the authority of the EU, which is seeking to take up the leadership, is seen as being weaker. If the US and China could agree, usually everybody would fall into place behind them but now there’s no one who can pull back on China.

Under the Paris accord, more than 190 nations pledged to work together to limit global warming to well below 2C, but it is up to each country to set its own targets. China wants developing countries to have more relaxed reporting standards than developed ones, because they may lack the capacity for complex emissions modelling. The US and EU are among those who want all countries to have the same rules for emissions reporting, with a limited degree of flexibility for the least developed countries. Beijing has also insisted that it should be treated as a developing nation, despite being on purchasing power parity the world’s largest economy.

“The big question is which China will turn up? We know the leadership in Beijing supports the Paris agreement. It needs to help deliver a strong set of rules and redirect finance away from coal. We used to be more passive participants, and now we’re more proactive” (Xie Zhenhua, China’s lead climate negotiator).

So, what is next?

Recent efforts to cut overcapacity are the starting-point. It is concentrated in high-emission industries such as steel and coal, whose capacity the government wants to control. Industrial businesses will feel the force of strict carbon-emissions regulations. This links progress to economic reforms and efforts to improve regional industrial structures.

China’s emphasis must move from mitigation of climate change to adaptation to it. That involves upgrading infrastructure, changing lifestyles and further raising public consciousness. In the long run, as China’s industries shift from manufacturing to services, social resistance to the economic effects of climate-change action will decrease.

Giulia Galli