The 1st of June 2017, Trump announced the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. This decision had – and will continue to have - deep repercussions on the process of international climate cooperation, undercutting the foundation of global climate governance and undermining the universality of the Paris Agreement. In particular, it impairs states' confidence in climate cooperation and it aggravates the leadership deficit in addressing global climate issues. Indeed, the withdrawal reduces other countries' emission space and raises their emission costs, and refusal to contribute to climate aid makes it more difficult for developing countries to mitigate and adapt to climate change. Cutting climate research funding will compromise the quality of future IPCC (Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change) reports and ultimately undermine the scientific authority of future climate negotiations. On the other hand, China is facing mounting pressure from the international community to assume global climate leadership after the US withdrawal, but still needs to keep the US engaged in climate cooperation in the hope of achieving significant results.

Despite this decision from the US presidency, thousands of groups across the United States—including cities, states, companies, tribes and nongovernmental organizations—have launched initiatives in support of the Paris Agreement. Among others, US Climate Alliance, We Are Still In, and America’s Pledge, were a major part of the US presence in last November at the U.N. climate negotiations and demonstrated that millions of Americans remain committed to climate action. Indeed, states and cities supporting the agreement now represent nearly half of the US population and, combined, make up more than half of US GDP.

On the other hand, multilateral climate funds such as the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF) hold particular significance internationally due to their inclusive participation, concessional resources and focus on implementation of the Agreement. With the current U.S. presidential administration retreating from international climate finance, non-federal actors need to step in, at least for now, to help fill the vacuum. This is at this turning point that the Center for American Progress and World Resources Institute proposed creating a finance vehicle, called the America’s Climate Fund. The fund could accept contributions from a variety of US sources—including via a crowd-funding campaign—and channel these contributions to support low-carbon development and climate-resilience in developing countries.

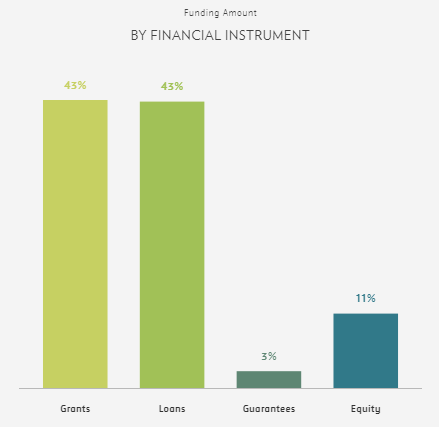

Under former President Barack Obama, the United States pledged $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a multilateral fund that provides grants, loans, and equity financing for projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote climate adaptation, particularly in the poorest and most vulnerable countries. The GCF has approved $2.2 billion for 43 projects since the fund became operational in 2015—from renewable energy in the Pacific islands to flood early-warning systems in Malawi—and has many more projects in the pipeline.

Despite this decision from the US presidency, thousands of groups across the United States—including cities, states, companies, tribes and nongovernmental organizations—have launched initiatives in support of the Paris Agreement. Among others, US Climate Alliance, We Are Still In, and America’s Pledge, were a major part of the US presence in last November at the U.N. climate negotiations and demonstrated that millions of Americans remain committed to climate action. Indeed, states and cities supporting the agreement now represent nearly half of the US population and, combined, make up more than half of US GDP.

On the other hand, multilateral climate funds such as the Adaptation Fund, the Least Developed Countries Fund (LDCF) and the Green Climate Fund (GCF) hold particular significance internationally due to their inclusive participation, concessional resources and focus on implementation of the Agreement. With the current U.S. presidential administration retreating from international climate finance, non-federal actors need to step in, at least for now, to help fill the vacuum. This is at this turning point that the Center for American Progress and World Resources Institute proposed creating a finance vehicle, called the America’s Climate Fund. The fund could accept contributions from a variety of US sources—including via a crowd-funding campaign—and channel these contributions to support low-carbon development and climate-resilience in developing countries.

Under former President Barack Obama, the United States pledged $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund (GCF), a multilateral fund that provides grants, loans, and equity financing for projects that reduce greenhouse gas emissions and promote climate adaptation, particularly in the poorest and most vulnerable countries. The GCF has approved $2.2 billion for 43 projects since the fund became operational in 2015—from renewable energy in the Pacific islands to flood early-warning systems in Malawi—and has many more projects in the pipeline.

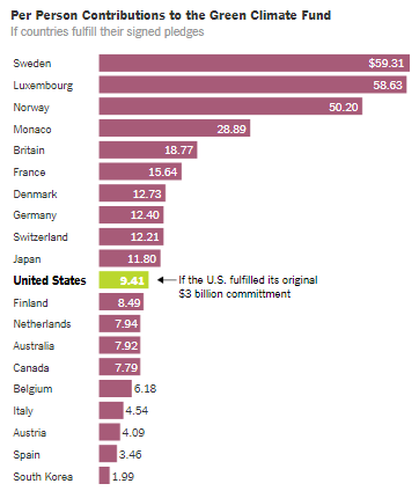

So far, the United States has delivered $1 billion to the GCF. The current administration, however, has targeted contributions to the GCF for elimination in its 2018 federal budget proposal. If the United States contributed its full pledge, the total would be a little less than $10 per American. With Mr. Trump stopping payments, the United States will have contributed $1 billion, or just more than $3 per person.

America’s Climate Fund would not lessen the responsibility of the federal government to provide international climate finance— and it would not fill the $2 billion gap between the amount of funding the United States has promised and has delivered to the GCF. However, the fund would serve a number of important purposes, both domestically and internationally. An initial goal of several tens of millions of dollars, for instance, would be a meaningful signal that Americans remain engaged in the global climate effort. Furthermore, the fund could also potentially facilitate increased climate finance from other donor countries.

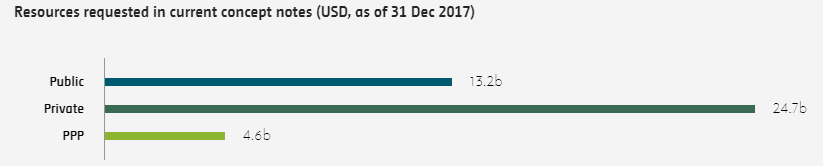

The America’s Climate Fund would have 2 ways to disburse contributions: direct contributions and co-financing. Direct contributions will be made to existing multilateral climate funds that are already supporting projects that promote clean energy or climate preparedness in developing countries. Indeed, making direct contributions to projects in developing countries would entail large start-up costs, contributing to existing multilateral institutions is therefore likely to be more efficient. For instance, the America’s Climate Fund could disburse 50 percent of funding raised to the Adaptation Fund and 50 percent to the Green Climate Fund. Public, private and PPP initiatives will be supported thanks to the diversity of the Green Climate Fund portfolio.

The America’s Climate Fund would have 2 ways to disburse contributions: direct contributions and co-financing. Direct contributions will be made to existing multilateral climate funds that are already supporting projects that promote clean energy or climate preparedness in developing countries. Indeed, making direct contributions to projects in developing countries would entail large start-up costs, contributing to existing multilateral institutions is therefore likely to be more efficient. For instance, the America’s Climate Fund could disburse 50 percent of funding raised to the Adaptation Fund and 50 percent to the Green Climate Fund. Public, private and PPP initiatives will be supported thanks to the diversity of the Green Climate Fund portfolio.

The fund could also support individual projects that promote low-carbon and climate-resilient development. For example, it could co-finance projects from the pipelines of existing multilateral climate funds. This would allow the non-federal climate movement to support projects that satisfy its priorities, which could include food and water security in the poorest nations or the phase-out of coal-fired power plants. However, this approach would entail higher costs for staffing, administration, governance, and monitoring and evaluation than direct contributions to existing funds.

Internationally, the fund would demonstrate that the United States remains a player in the global fight against climate change, which can be spotlighted at upcoming international events, such as the Global Climate Action summit scheduled in California in next September. This coming meeting will bring people together from around the world to showcase climate action and inspire deeper commitments from national governments in support of the Paris Agreement. The America’s Climate Fund will be – for sure – one of the discussed topics.

Célia Bellec

Internationally, the fund would demonstrate that the United States remains a player in the global fight against climate change, which can be spotlighted at upcoming international events, such as the Global Climate Action summit scheduled in California in next September. This coming meeting will bring people together from around the world to showcase climate action and inspire deeper commitments from national governments in support of the Paris Agreement. The America’s Climate Fund will be – for sure – one of the discussed topics.

Célia Bellec