In this article we review the recent controversy surrounding Ernst & Young and the proposed Project Everest, which would split the audit and consulting arms of their business. This model has been commonly seen among other firms such as Cherry Bekaert and EisnerAmper. It has been trending for some time now since it is not only advantageous for handling potential conflicts of interest among the firms’ clients, but it also allows for much larger revenue potential to be unlocked. With regard to Ernst & Young, the potential split is however more complex and currently facing backlash from the firm’s U.S. partners.

The Current State and Company Overview of Ernst & Young

Ernst & Young has been at the center of attention recently thanks to its so-called Project Everest plan to spin off its Advisory arm, but before delving into its current state, we will examine the company.

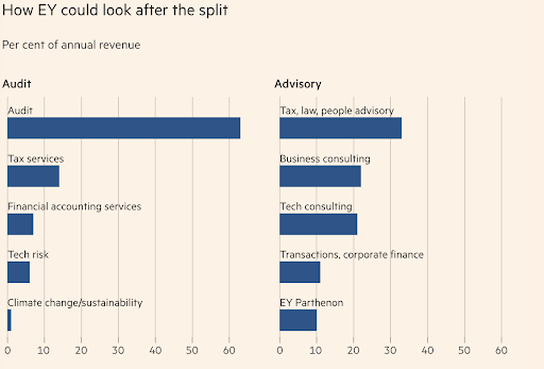

Ernst & Young LLP (EY) is a global professional services firm headquartered in London, England. It is one of the Big Four accounting companies along with Deloitte, KPMG and PwC. The firm offers various services, including audit, consulting, tax, law, technology, and human resources, among others. The company operates with a traditional partnership model in over 150 countries, and it recorded its biggest global revenue in nearly two decades in its fiscal year (FY) 2022, with $45.4 billion USD, up 13.7% from the previous financial year. The majority of the revenue comes from the Assurance Service Line with around 32%, while Tax accounting for 25%, Strategy and Transactions for 13% and Consulting for 30%, the latter being the fastest growing with 25% year-on-year revenue growth.

EY is a result of numerous mergers. In 1903, Alwin C. Ernst and Theodore Ernst founded Ernst & Ernst, a small accounting firm in Cleveland. Across the pond, Whinney Murray & Co. was founded in 1849 in England, making it the oldest among EY’s ancestor companies. A couple decades later, in 1979, the 35 year old partnership between Ernst & Ernst and Whinney Murray & Co. resulted in a merger, creating Ernst & Whinney. 10 years later, in 1989, Ernst & Young was born with another merger between Ernst & Whinney and Arthur Young & Co (a firm established in 1906 based in Chicago). It is possible that the next substantial change in the company’s life is just around the corner, in the form of Project Everest’s spin-off the firm’s advisory arm.

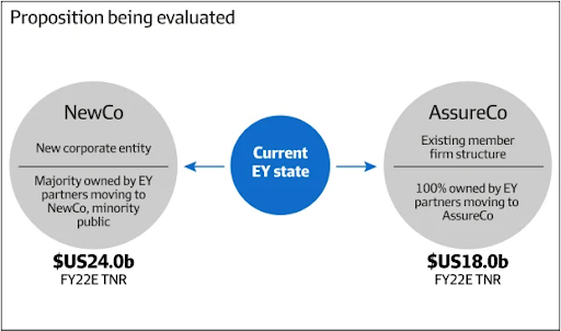

The news about separating EY into two distinct organizations was first reported last May and confirmed by the company in September. The general rationale being: to avoid conflicts of interest, accounting companies are restricted to acting both as an auditor and as an advisor for the same firm, hence limiting the target companies for both of the segments. Consequently, splitting the company into two independent businesses would lift these restrictions from both new entities, liberating them. For example, the new advisory company would be able to do business with approximately one third of the S&P 500 companies, including tech giants such as Google and Amazon, which they are currently prohibited from providing consulting services to since EY acts as an auditor for them. However, it is not all roses when it comes to the spin-off in the case of EY.

The Current State and Company Overview of Ernst & Young

Ernst & Young has been at the center of attention recently thanks to its so-called Project Everest plan to spin off its Advisory arm, but before delving into its current state, we will examine the company.

Ernst & Young LLP (EY) is a global professional services firm headquartered in London, England. It is one of the Big Four accounting companies along with Deloitte, KPMG and PwC. The firm offers various services, including audit, consulting, tax, law, technology, and human resources, among others. The company operates with a traditional partnership model in over 150 countries, and it recorded its biggest global revenue in nearly two decades in its fiscal year (FY) 2022, with $45.4 billion USD, up 13.7% from the previous financial year. The majority of the revenue comes from the Assurance Service Line with around 32%, while Tax accounting for 25%, Strategy and Transactions for 13% and Consulting for 30%, the latter being the fastest growing with 25% year-on-year revenue growth.

EY is a result of numerous mergers. In 1903, Alwin C. Ernst and Theodore Ernst founded Ernst & Ernst, a small accounting firm in Cleveland. Across the pond, Whinney Murray & Co. was founded in 1849 in England, making it the oldest among EY’s ancestor companies. A couple decades later, in 1979, the 35 year old partnership between Ernst & Ernst and Whinney Murray & Co. resulted in a merger, creating Ernst & Whinney. 10 years later, in 1989, Ernst & Young was born with another merger between Ernst & Whinney and Arthur Young & Co (a firm established in 1906 based in Chicago). It is possible that the next substantial change in the company’s life is just around the corner, in the form of Project Everest’s spin-off the firm’s advisory arm.

The news about separating EY into two distinct organizations was first reported last May and confirmed by the company in September. The general rationale being: to avoid conflicts of interest, accounting companies are restricted to acting both as an auditor and as an advisor for the same firm, hence limiting the target companies for both of the segments. Consequently, splitting the company into two independent businesses would lift these restrictions from both new entities, liberating them. For example, the new advisory company would be able to do business with approximately one third of the S&P 500 companies, including tech giants such as Google and Amazon, which they are currently prohibited from providing consulting services to since EY acts as an auditor for them. However, it is not all roses when it comes to the spin-off in the case of EY.

Source: Ernst & Young

Multiple obstacles have risen since Project Everest was announced. One of the biggest concerns is the split of the current tax division of EY, which is linked to both the audit and the consulting area of the firm. There is a reported disagreement among U.S. partners about what percentage of the tax business or staff should be retained by the audit firm. EY expects to receive around $11.5 billion USD with the sale of the 15% in the IPO, which would result in a market capitalization of around $77 billion. The firm would also raise $30 billion USD to pay the 6000 partners staying with the audit arm and to pay off some liabilities. Another problem is that the cost of debt has significantly increased since Project Everest was proposed. Additionally, given the attention and coverage that the plan has attracted, there is a serious reputational risk surrounding it and its implementation.

Even if everything had gone smoothly with the discussions concerning spin-off, its implementation would not be easy due to EY’s organizational structure. According to Financial Times, “EY is an alliance of locally owned firms that share a brand, technology and common standards, all of which are overseen by a global organization to which each country pays a fee.” This implies that every company in each different country would have to approve the plan with their own rules and then figure out how to split the partners and employees between the new and the old company. For example, in the U.S., two-thirds, and in the UK, 75% of the partners should vote in favor of the plan for it to pass. According to a poll carried out by Fishbowl, a social media platform for professionals, among EY employees in the U.S., 38.5% of the respondents said they support the split, while 29.5% said they did not. EY called the findings “unrepresentative and unreliable.” On the other hand, some insiders in EY say that the sentiment among partners, who will actually be the deciding body, is positive. Either way, how its 13,000 partners vote will be decisive for EY’s history. However, concerns about Project Everest, such as the ones recently raised by EY Americas Area Managing Partner and EY U.S. Chair and Managing Partner, Julie Boland, signal that the split is not exactly going according to plan.

Even if everything had gone smoothly with the discussions concerning spin-off, its implementation would not be easy due to EY’s organizational structure. According to Financial Times, “EY is an alliance of locally owned firms that share a brand, technology and common standards, all of which are overseen by a global organization to which each country pays a fee.” This implies that every company in each different country would have to approve the plan with their own rules and then figure out how to split the partners and employees between the new and the old company. For example, in the U.S., two-thirds, and in the UK, 75% of the partners should vote in favor of the plan for it to pass. According to a poll carried out by Fishbowl, a social media platform for professionals, among EY employees in the U.S., 38.5% of the respondents said they support the split, while 29.5% said they did not. EY called the findings “unrepresentative and unreliable.” On the other hand, some insiders in EY say that the sentiment among partners, who will actually be the deciding body, is positive. Either way, how its 13,000 partners vote will be decisive for EY’s history. However, concerns about Project Everest, such as the ones recently raised by EY Americas Area Managing Partner and EY U.S. Chair and Managing Partner, Julie Boland, signal that the split is not exactly going according to plan.

Theoretical Background and Past Cases: Cherry Bekaert and EisnerAmper

The decision by Ernst & Young to divide the two divisions is by no means a first or an exclusive one among companies that operate in both the auditing and consulting industries. Many companies have already followed this path, and this decision comes in response to concerns about continuous conflicts of interest between the two business units. In this section of the article, we will explore what conflicts of interest are and which ones are involved among consulting and auditing. Next, we will look at how the split of consulting and auditing is now becoming a common restructuring procedure, especially after the acquisitions of equity stakes by new coming investors, by providing the example of the recent Cherry Bekaert deal.

A conflict of interest occurs when a person or group has opposing loyalties or interests that might affect their ability to act impartially or objectively. These conflicts occur in the context of auditing and consulting when an auditor or consulting business offers services to a client that might jeopardize their objectivity or independence. An auditor traditionally reviews a company's records and monitors the quality of information generated by the company in order to reduce the inherent information imbalance between the firm's managers and its shareholders. Nonetheless, when a firm provides both auditing and nonaudit consulting services to its clients, such as tax, accounting, management information systems, and business strategy advice, it allows for economies of scale and scope efficiencies, but it also presents primarily two potential sources of conflict of interest.

The first is when auditors are willing to skew their judgments and conclusions in order to acquire advisory work from the same customers. This conflict is especially significant because consulting services are frequently more profitable for audit firms than audit services, and as a result, the auditor may be under pressure to provide a more favorable audit opinion in order to maintain their relationship with the client and win consulting work. Many countries have rules and regulations in place to resolve this conflict of interest, limiting the types of advisory services that auditors can provide to their audit customers. In the United States, for example, the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 restricts accounting companies from providing some types of consulting services to their audit clients, such as bookkeeping or internal audit services. Furthermore, auditors must disclose to their clients any potential conflicts of interest and take steps to mitigate these conflicts. Over the years, the Act in question has proven to be somehow effective, which is the reason why an increasing number of accounting firms are proceeding to restructure their businesses, so that they can operate in a more liberal environment.

The second conflict that could emerge is due to the fact that auditors may be examining information systems or tax and financial strategies implemented by non-audit counterparts within the organization, and hence may be hesitant to criticize the systems or recommendation, since they would lead to loss of a clients in terms of the non-auditing services provided by the firm. As a result, audits may be skewed toward the client's interests rather than delivering an impartial and independent view on the financial statements.

Considering that, as aforementioned, auditors are shareholders’ first line of defense against dodgy accounting, the SEC is constantly and strictly monitoring accounting firms to assure that an independent judgment is preserved, as proven by the fact that all Big 4 (KPMG, EY, PwC, Deloitte) have paid fines to such authority since 2014 to settle prior regulatory investigations of audit independence violations. For instance, PwC paid nearly $8 million to settle SEC charges that it assisted an audit client in designing software that was part of its accounting-compliance systems in 2019. According to the SEC settlement decision, the arrangement breached audit-independence regulations by putting PwC in the position of potentially auditing its own project-management functions. EY, on its part, had to settle without admitting or denying wrongdoing twice with the SEC in the last eight years when the SEC claimed that independence guidelines were infringed, respectively paying $4 million and $10 million dollars in 2014 and 2020. Other sanctions cases include KPMG paying $8.2 million to settle an SEC probe alleging that it supplied prohibited nonaudit services, such as bookkeeping, to affiliates of companies whose books it audited in 2014 and Deloitte settling a SEC enforcement action alleging audit independence violations in 2015 for $1.1 million.

For the reasons presented and the strongly regulated environment, companies such as Cherry Bekaert and EisnerAmper, after being acquired by private equity funds, have preferred to restructure to boost revenues and operate freely.

Cherry Bekaert is an American accounting firm. With over 25 offices throughout the United States and 1350 employees, it provides services such as audit, assurance, tax planning, and wealth management to its clients in a variety of industries. The firm was founded in 1947 by Harry Cherry, who started a small practice in North Carolina. By 1953 Charles Bekaert and William Holland had joined the firm, which was renamed Cherry Bekaert and Holland. In 2022, the company announced that Parthenon Capital had made a strategic investment in the firm’s business advisory practices.

Parthenon Capital is a leading growth-oriented private equity firm with approximately $2 billion of assets under management. The company invests in middle-market companies with enterprise values of $50 million to $500 million that have strong potential for sustainable growth and value creation. It mainly focuses on insurance and financial services, healthcare, and information technology.

On 30 June 2022, Parthenon Capital purchased a stake in Cherry Bekaert: financial details were not disclosed, but the investment resulted in the division between the advisory and the audit practice, splitting the company into two independently owned entities, Cherry Bekaert LLP and Cherry Bekaert Advisory LLC. Parthenon Capital aimed to reduce conflict of interest and increase the services offered and innovative ability of each division. Andrew Dodson, Managing Partner of Parthenon Capital, believes that through strategic acquisitions and collaboration, this deal will bring “the firm to achieve its full potential as one of the country’s leading professional services organizations.”

The management structure was not strongly altered. Colin Hill, who had worked at Cherry Bekaert since 2003, was appointed Managing Partner of Cherry Bekaert LLP, a licensed CPA, which provides attest services. Cherry Bekaert LLC, run by CEO Michelle Thompson, provides business advisory and non-attest services, spanning the areas of transaction advisory, risk and accounting advisory, digital solutions, cybersecurity, tax, benefits consulting, and wealth management. “We are excited about Parthenon’s commitment to provide additional investment in technology, infrastructure and other key areas” said CEO Michelle Thompson, who believes that this restructuring offers a wide range of opportunities to improve the firm’s offerings in its fundamental practices.

This framework reminds us of the Towerbrook-EisnerAmper deal. EisnerAmper is one of the largest accounting, tax and business advisory firms in the U.S., with more than 3,000 employees and 300 partners across the country. TowerBrook Capital Partners is an international investment management firm, headquartered in London and New York City, focused on control-oriented investments, with the goal of improvement and value creation. In August 2021, TowerBrook acquired EisnerAmper LLP. The amount of the transaction was not disclosed, but Charly Weinstein, CEO of EisnerAmper, described it as "significant”. With this deal EisnerAmper LLP, which continued to provide attest services as a licensed CPA, separated the non-attest side into an entity called Eisner Advisory Group LLC, which would offer business advisory and non-attest services. This operation inflated EisnerAmper potential: the company’s revenue in 2021 was $411 million, but EisnerAmper Advisory Group LLC, backed by mergers and acquisitions in the U.S, is targeting to grow its revenue to $725 million for 2023. The ambitious aim to nearly double revenues in just two years reflects the magnitude of the effect such a split can have.

The enthusiasm of these firms’ CEOs suggests that splitting has proven to be advantageous. However, while Cherry Bekaert and EisnerAmper have followed the recent trend of big companies splitting, EY has experienced a series of delays in its plan to divide its global auditing and consulting businesses.

Controversy Surrounding Project Everest: An Analysis

When it comes to EY, as soon as news emerged about a possible split, many controversial opinions began to form concerning the bold plan. Among all of the voices in the herd, one the public has become familiar with is Julie Boland’s, EY’s US Chair and Managing Partner and Americas Managing Partner.

After the recent statements issued by both EY US and Boland herself, it does not come as a surprise that she is a strong advocate for the abolition of Project Everest, citing the long term health and vision alignment issues as the main reasons for her doubts.

For the sake of completeness, before digging deeper into the specific reasons offered by professionals familiar with the matter, we will review some of the key reasons, cited by publications and newspapers, in favor of moving forward with the split.

- Conflicts of Interest: One major disadvantage of the existing model is the potential for conflicts of interest. When a firm provides both audit and consulting services to a client, there may be pressure to provide a favorable audit report in order to maintain the consulting relationship. This can undermine the independence of the audit process and make it difficult for auditors to remain impartial.

For example, if a consulting team is helping a client implement a new financial system, the audit team may be hesitant to report any weaknesses in the system that could reflect poorly on the consulting team's work. This can lead to a situation where the audit report is less reliable and accurate than it should be. - Reputation Risk: A second disadvantage of the model is the potential for reputation risk. When a firm provides both audit and consulting services, any scandal or controversy related to the consulting services can reflect poorly on the firm's audit services as well. This can damage the firm's reputation and make it more difficult for them to attract and retain clients.

Source: Financial Times (produced using Ernst & Young internal figures)

For what it concerns EY U.S, specific reasons, Boland listed four pivotal points for the deal to take place:

All of the scenarios described thus far become even more complicated once we consider the fact that they are also deeply interconnected, which means it becomes increasingly harder to estimate the true extent of potential negative externalities.

- Which partners should be allocated to which business sector/desk?

In a firm such as the Big 4, but in particular EY, partners tend to manage multiple sides of the business in order to guarantee continuity and, to some extent, limit redundancy.

Cutting the firm in half would require partners that have interests (and most importantly, clients) on both sides to choose. This might negatively impact the side of business that they are abandoning. - How could EY oversee the alignment of the strategies of the two new organizations?

If EY was to split, this could also result in less cooperation between the new firms when pursuing common policies and long term objectives. This point is particularly relevant in the U.S. where lobbying plays a crucial role when it comes to the external policy agenda.

The lobbying industry is severely regulated, hence it would be increasingly hard for the new companies to push on the same issues and remain fully aligned if regulators required them to act as two distinct entities. - How can EY ensure the health of the global network for the less-profitable, audit-dominated side of the business?

It may not come as a surprise that in 2023 audit is not as profitable as consulting or deal advisory. Consequently, one of the new firms would be in a weaker market position compared to its rivals. - How deeply would the split impact EY’s ability to execute and deliver the EBITDA required for any transaction?

Among the benefits usually mentioned when discussing uniting more business areas under the same objective, one is surely the concept of economies of scope; economies which, in the case Project Everest passes, will no longer contribute to the margin secured by EY’s services to its clients.

All of the scenarios described thus far become even more complicated once we consider the fact that they are also deeply interconnected, which means it becomes increasingly harder to estimate the true extent of potential negative externalities.

Conclusion

Ultimately, an eventual split of EY would result in one of the largest shocks the accounting industry has faced since the Arthur Andersen scandal of 2001. Following our analysis, the proposed transaction is much more complex than the other cases evaluated in which the split has been employed. There are still many questions regarding how the concerns of the U.S. partners would be handled. Given this uncertainty, Project Everest is now at a standstill and it remains unclear as to whether the split could be accomplished effectively. However, if successful, EY could go on to innovate key areas of its business as seen in the cases of Cherry Bekaert and EisnerAmper.

By Stefano Graziosi, Matteo Panizza, Sofia Rubino, Mihály Schieszler

SOURCES

Alyssa Schukar for The Wall Street Journal. “WSJ News Exclusive | Big Four Accounting Firms Come under Regulator's Scrutiny.” The Wall Street Journal, Dow Jones & Company, 15 Mar. 2022, https://www.wsj.com/articles/big-four-accounting-firms-come-under-regulators-scrutiny-11647364574?mod=hp_lead_pos3.

Blokhin, Andriy. “The Impact of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002.” Investopedia, Investopedia, 13 July 2022, https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/052815/what-impact-did-sarbanesoxley-act-have-corporate-governance-united-states.asp#:~:text=The%20Sarbanes%2DOxley%20Act%20of%202002%20was%20passed%20by%20Congress,accurate%20handling%20of%20financial%20reports.

Brewer K. Drew J., “Top 25 firm Cherry Bekaert reveals transformative private equity investment”. Journal of accountancy, June 30 2022

https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/news/2022/jun/cherry-bekaert-private-equity-investment.html

“Cherry Bekaert Announces Strategic Investment from Parthenon Capital”, Cherry Bekaert, June 30 2022

https://www.cbh.com/firm-news/cherry-bekaert-announces-strategic-investment-from-parthenon-capital/

Drew J., “Private equity’s push into accounting”. Journal of accountancy, October 6 2021

https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/news/2021/oct/private-equity-push-into-accounting.html

“EisnerAmper Announces Investment by TowerBrook Capital Partners”. EisnerAmper, August 2 2021

https://www.eisneramper.com/towerbrook-capital-partners-investment-news-0721/

Foley Stephen, “US accounting industry split on taking private equity cash”. Financial Times, November 7 2022.

https://www.ft.com/content/221830e1-68d6-4d83-9c9b-4327305a022f

Foley, Stephen, and Michael O'Dwyer. “Ey Us Boss Signaled Wide-Ranging Concerns over Split.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 13 Mar. 2023,

https://www.ft.com/content/a8b3f284-944b-4302-901a-8ddca7ba0243.

Foley, Stephen, and Michael O'Dwyer. “'Frustration and Chaos': Ey Fights to Save Project Everest after US Rebellion.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 10 Mar. 2023, https://www.ft.com/content/5a084b56-6d1e-4982-b5f7-ab98161fad01 .

Foley, Stephen, and Michael O'Dwyer. “To Split or Not to Split: Ey Confronts the Question.” Financial Times, Financial Times, 6 Mar. 2023,

https://www.ft.com/content/443cea94-8ded-45fc-93df-8b09a750728d.

Industry Expertise, Parthenon Capital

https://www.parthenoncapital.com/about-us/industry-expertise/

Lloyd, Rachel. “EY Achieves Highest Growth in Nearly Two Decades, Reports Record Global Revenue of US$45.4B.” EY, EY, 21 Sep. 2022,

https://www.ey.com/en_gl/news/2022/09/ey-achieves-highest-growth-in-nearly-two-decades-reports-record-global-revenue-of-us45-4b.

Lloyd, Rachel. “Statement on the Future of the EY Organization.” EY, EY, 8 Sep. 2022, https://www.ey.com/en_gl/news/2022/09/statement-on-the-future-of-the-ey-organization.

Mishkin, Frederic S., and Stanley G. Eakins. Ch. 7 “Why Do Financial Institutions Exist?”, Financial Markets and Institutions, Pearson, Hoboken, NJ, 2018.

Michaels, Dave. “SEC Probes Big Four Accounting Firms over Conflicts of Interest.” Financial News, Financial News, 16 Mar. 2022, https://www.fnlondon.com/articles/sec-probes-big-four-accounting-firms-over-conflicts-of-interest-20220316.

Sussman, Anna. “Separating Auditing from Consulting: More Complex than It Seems.” UCLA Anderson Review, 10 Nov. 2021, https://anderson-review.ucla.edu/separating-auditing-from-consulting-more-complex-than-it-seems/.