In April 2016, millions of files were leaked from the database of the Panamanian law firm Mossack Fonseca. The files incriminated many elites and exposed the world of offshore transactions. Despite Panama’s positioning as a tax haven and importance to world trade, this scandal was a severe setback that caused many in the global community to question foreign investment in Panama. Since then, Panama has taken steps to recover and reposition its economy. In this article, we will provide an overview of Panama’s economy, the effect of the Panama Papers, and what has changed since.

A Brief History of Panama's Economy

For more than a century, Panama has steadily expanded, becoming one of the top economies in the area and a center for international trade and investment.

Given that Panama is a relatively safe and stable destination in comparison to other Central American countries in Central America, it is popular in terms of business and tourism worldwide.

However, the Panama Canal, which was built in partnership with the U.S. over a period of nearly 30 years around the turn of the 20th-century, was a game-changer for international trade and maritime transportation. Arguably, it was the most significant contributor to Panama's national growth. Not only did it bring an influx of people and money , solidifying economic growth and development, but it also supported international relations and created a political safety-net through its relationship with the United States.

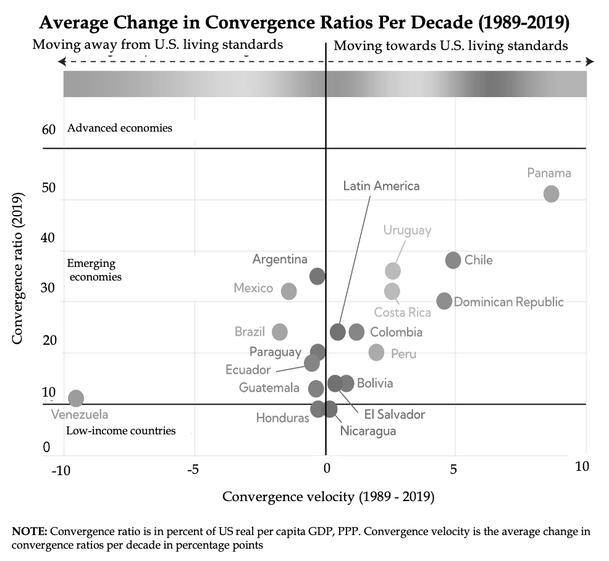

In fact, Panama is one of the most interesting countries when thinking about the phenomenon of “convergence” with the United States, which is usually measured using the ratio of the GDP per capita of Latin American countries to that of the United States. Over the past 25 years, Panama showed the highest convergence velocity, at about 8.5 percentage points per decade — 17 times faster than the average for the region.

Source: World Economic Outlook

A key factor of this impressive growth is the increase in investments, which led to rapid capital accumulation in the country. The prolonged investment boom has been underpinned largely by Panama’s geographic location and trade openness since Panama’s Colón Free Zone is the second largest in the world after Hong Kong SAR.

The Colón Free Zone, which was established in the mid-20th century at the northern end of the canal, has grown in significance as a hub for manufacturing, warehousing, and re-exporting.

Contraband commerce has been popular in Panama since the colonial era among individuals looking to dodge taxes or other government regulations, and in the late 20th-century, Panama became a major transshipment center for smuggling drugs. Until 1999, the U.S. military directed a regional drug interdiction program from Panama, but narcotics traffic decreased only partly, and the rate of drug consumption Panamanians soared in the 1990s. Cocaine and heroin are still transported through Panama on their way to North America, Europe, and other places.

The Colón Free Zone, which was established in the mid-20th century at the northern end of the canal, has grown in significance as a hub for manufacturing, warehousing, and re-exporting.

Contraband commerce has been popular in Panama since the colonial era among individuals looking to dodge taxes or other government regulations, and in the late 20th-century, Panama became a major transshipment center for smuggling drugs. Until 1999, the U.S. military directed a regional drug interdiction program from Panama, but narcotics traffic decreased only partly, and the rate of drug consumption Panamanians soared in the 1990s. Cocaine and heroin are still transported through Panama on their way to North America, Europe, and other places.

Global Finance in Panama

Banking and finance are two major pillars of Panama’s economy. In 1970, the Panamanian government began to promote offshore banking by giving international transactions tax- exempt status, and it also removed other forms of regulation. During the Noriega dictatorship in the 1980s, Panama lost its status as a banking and sanctuary free trade zone. Following the successful restoration of democracy, Panama bounced back to reclaim its position as the main financial and trading tax haven for the Western Hemisphere.

In fact, among the international finance community, Panama is known as the "Switzerland of Latin America," which is definitely a well-deserved moniker. Many international financial institutions as well as some of the biggest banks in Latin America are based in the nation. Panama's banking sector is second only to Switzerland in terms of sophistication and success. Panama's currency, the balboa, is pegged to the US dollar, making it a safe haven for investments. Many multinational corporations have moved their headquarters there.

Evidently, Panama's image as a "tax haven" is supported by the 35,000 international holding corporations and tax sanctuary businesses operating there. Panama has comparatively relaxed tax laws. All income and sales proceeds earned outside of Panama are tax-exempt, whereas all income and sales proceeds made inside Panama are subject to Panamanian tax. Panama uses the territorial method of taxation. In fact, Panama is the second most popular jurisdiction in the world, next to Hong Kong, with 400,000 corporations & foundations domiciled in the country. This is because Panama does not impose any reporting requirements or taxes (no income, capital gains, interest income, sales, capital, property, or estate tax is imposed). Additionally, Panama does not “pierce the corporate veil,” meaning business owners are not held personally liable for their actions in the business. There is also anonymous ownership and control, no paid-in capital requirement, and no levies or restrictions on the transfer of funds. In fact, money can be moved freely within and outside of the nation, regardless of the reason.

We can conclude that thanks to its strategic location, robust infrastructure, and favorable business environment, Panama is well positioned as a leading economic power in Latin America.

Overview of the Panama Papers (2016)

The Panama Papers refers to one of the most significant offshore leaks in history. In April 2016, more than 11 million files were leaked from the database of the law firm Mossack Fonseca by an anonymous source using the name John Doe. They passed the documents to the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, which then passed those on to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), who helped to process the data. More than 370 journalists from 76 different countries worked for one year on the data and eventually, ICIJ shared it with multiple partner newspapers. The data leak was unprecedented and the biggest at the time it happened. It mainly consisted of emails, databases, PDFs and pictures about 215 thousand offshore companies including data from 1977 to 2015 and was 2.6 terabytes. For comparison, the size of the data leaked in WikiLeaks was only 1.7 gigabytes.

Mossack Fonseca was a law firm based in Panama. It helped its clients to establish and to run offshore shell companies and was one of the biggest firms of its kind in the world. Its operations were global, with offices in 42 countries at the time. In 2018 the company was shut down “due to the economic and reputational damage inflicted by the disclosure of its role in global tax evasion by the Panama Papers.”

The leaked documents exposed the world of offshore and its connection to the elite like nothing before. Links were found by BBC to 72 current or former heads of state. For example, it turned out that Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson had a secret share in an offshore company in the British Virgin Islands that held his wife’s interest in Icelandic banks, worth multiple million dollars, and of course nobody knew about it when he was dealing with the Icelandic banks in the Icelandic financial crisis. Also, the papers revealed that multiple billions of pounds flowed into the London real estate market through offshore companies; for example, Sheikh Khalifa bin Zayed Al Nahyan, the president of the United Arab Emirates at the time, built one of the biggest real estate portfolios in England, owning multiple properties in Central London through offshore companies. Additionally, among many other high-ranking politicians and businessmen from around the world, the then prime minister of Pakistan, the Nigerian senate president and Iraq’s former interim prime minister were linked to London real estate through the leaked files. The documents also shined light on the incredible fortune of Vladimir Putin’s inner circle, the offshore fund of the then United Kingdom Prime Minister David Cameron’s father, Andrej Babiš’ offshore company owning a 22-million-dollar French villa and another offshore company of Petro Poroshenko, the Ukrainian president at the time, founded just a couple of months after his election. Companies linked to the president of China, Xi Jinping’s family, were also found. Apart from the numerous politicians and businessmen, many celebrities’ names were also found in the documents. English actress Emma Watson, Hong Kong actor Jackie Chan, former Formula 1 driver and World Champion Nico Rosberg and football legend Lionel Messi are all among the many celebrities included in the documents.

The Panama Papers caused a huge outburst and a series of scandals. For example, the above- mentioned Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson resigned as prime minister of Iceland after the Panama Papers revelations, and David Cameron was put under severe pressure by the public. The whistle-blower gave an interview to Spiegel last July, stating that they believe the Russian government wants to see them dead.

It is essential to note that apart from the obvious cases like fraud, corruption, money laundering, etc., in many cases, nothing illegal has happened. Usually, it is legal to own property or a firm through offshore companies. In these cases, the concerns and problems come from the moral side. What does it say about a politician’s credibility if they are not honest about their wealth and that they do not pay all the taxes to the country where they live? Furthermore, many celebrities mentioned in the papers often aim to be role models for society; this position can be easily questioned if they try to avoid paying taxes, hence contributing to the society. After the scandal, many politicians, including President Obama called for a change in the regulations concerning offshore activities.

What’s Changed Since the Panama Paper’s Release

The immediate aftermath of the Panama Papers was devastating for the country. The Panamanian economy was heavily dependent on its financial services industry, which accounted for about 90% of its GDP. The fact that it was now being portrayed as a hub for tax evasion and money laundering had an immediate impact: foreign investors withdrew their funds from Panamanian banks, and rating agencies downgraded the country’s credit rating. Panama was added to the blacklists of many countries, including the ones belonging to the European Union, making it more difficult for companies to do business with foreign partners and causing a deep loss of foreign investment. The Panamanian government had to act quickly to restore confidence and prevent a financial crisis.

The first step was to launch a thorough investigation into the allegations made in the leaked documents. The government set up an independent commission to investigate the matter, and over the following months, it analyzed thousands of pages of documents. The commission found evidence of a lot of high-profile individuals and companies using the country as a tax haven, but it also identified weaknesses in Panama's financial regulatory system. It highlighted how easy it was for companies to set up shell corporations and hide their wealth; the commission recommended changes to the present legislation to address these issues.

The government responded to the commission's findings by implementing a series of reforms to strengthen the country’s financial system: the first was to set up a new anti-money laundering agency, which would have the power to investigate and penalize banks and other financial institutions that broke the law. The government also introduced new rules, which required banks to verify the identities of their customers to prevent them from setting up shell corporations mentioned above. It also introduced new transparency measures such as requiring companies to disclose their beneficial owners.

These reforms were appreciated by international organizations such as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Both institutions had previously raised concerns about Panama's financial system in the past. In fact, Panama has almost completed the 15 conditions from its FATF Action Plan, which would allow it to be removed from the organization’s “grey list.” The FATF will meet later this year in June to revaluate Panama’s status.

Despite these reforms, the impact of the Panama Papers continues to be very significant in Panama. The country's GDP growth rate has slowed, and its budget deficit has grown, leading to concerns about its long-term financial stability. The country has historically been a tax haven, and many wealthy individuals and corporations continue to use it with this purpose. The government's reforms have made it more difficult for them to take advantage of it, but the problem has not been fully erased. The Panama Papers also damaged Panama's reputation as a safe and stable economic centre, making it more difficult for the country to attract foreign

investors, particularly those who are concerned about the reputational risks related to investing in Panama.

Panama's attempts to improve its reputation have also been delayed by the ongoing corruption scandals involving senior public officials. In 2018, the country's former president, Ricardo Martinelli, was arrested for embezzlement and wiretapping. Martinelli's successor, Juan Carlos Varela, was implicated in corruption scandals during his term as well. These scandals have further hindered public trust in the government and contributed to Panama's reputation as a country with a weak rule of law and prone to corruption.

Varela’s successor, Laurentino Cortizo, pledged an end to corruption when he took office in 2019. However, in his term of office his administration has been subject to many corruption scandals, among which we find the irregular purchase of COVID-19 related medical supplies. Cortizo has been accused by many of not respecting COVID-19 preventive measures and of offering excessive salaries and improperly using official vehicles, minimizing the effort necessary to fight corruption.

Overall, while the government's fast response and the prompt subsequent reforms have helped restoring confidence and address some of the weaknesses in Panama's financial system, damage from the Panama Papers scandal remains. There is still much work to be done, but the country is moving in the right path.

What’s Next: A Forward Outlook on Panama’s Economy

Despite the Panama Papers scandal, in recent years Panama’s economy has seen a period of remarkable growth and accelerated income convergence. In 2022, the economy continued its recovery from the deep recession caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, enabling GDP to exceed its pre-crisis level. Even though growth will remain relatively strong in 2023, it is nonetheless expected to decelerate in a weakening global economy. Moreover, the drivers of growth may change in the future.

While household consumption will continue to sustain economic activity, inflation will likely dampen it. Support measures introduced in response to the social movements of the summer of 2022, especially the likely continuation of subsidies for basic goods such as fuel and certain food products, will limit price increases and their effects on consumer spending. New private investment will be slowed by the rise in U.S., and hence Panamanian, interest rates. However, the country's role as a logistical hub and the presence of free trade zones are likely to remain supportive of investment. Investment in the manufacturing sector may increase as a result of the benefits and incentives that the government has provided to multinational corporations in order to make Panama a nearshoring center in Latin America. In addition, the government will continue to invest in infrastructure. Overall, in 2024–2027, GDP is expected to grow at an annual average of 4.1%, driven by infrastructure, transportation, tourism, and output from the Cobre Panamá copper mine with the help of the country's services-oriented model of economy..

The current President Laurentino Cortizo was elected in May 2019 for a five-year term. The government's priorities are fiscal consolidation and the fight against money laundering and corruption. The government faces public discontent, fueled by sluggish progress in the fight against clientelism and in the constitutional reforms promised. Fuel price increases have exacerbated discontent and contributed to the emergence of significant social movements in the summer of 2022. Even if the strikes and protests have stopped, people's trust in the government has not increased. Despite concessions in the general budget for 2023 and subsidies for energy and food products, social tensions are running high, increasing the likelihood of further social unrest. Governability risks will be contained by the government's legislative majority, but as the general election of May 2024 approaches and parties concentrate on their own candidates, the alliance's cohesiveness is likely to deteriorate.

The government is projected to fall slightly short of its goal to decrease the budget deficit from 5% of GDP in 2022 to 3% of GDP in 2023 and to 2% of GDP in 2024 due to the slowing economy and election expenditure pressures as concessions by the authorities following the protests will temper the spending reduction. However, fiscal consolidation is expected to continue. Overall, for 2023, despite the growing public debt burden amid rising interest rates, the deficit should continue decreasing.

Furthermore, while the country remains a preferred partner of the U.S., it has drawn closer to China for trade purposes. However, its openness towards China remains cautious. Since his election, President Cortizo has slowed Chinese investment in the Panama Canal. Moreover, Panama remains neutral in the Russian-Ukrainian war: commercial factors are the motivation why the Canal is not closed to Russian ships.

Finally, Panama’s past income convergence to levels of advanced economies was fueled by an enormous construction boom. To continue convergence, other productive sectors need to take over, governance must improve, and human capital advance. Diversifying the economy should be a priority, in particular, because of the dangers that de-globalization may stifle the expansion of international commerce, especially East-West trade, as a result of rising geopolitical tensions. Therefore, investing in human capital and TFP-enhancing innovation may be even more important to Panama's capacity to sustain robust and rapid development than investing in physical capital and construction projects.

To boost future competitiveness and economic potential, Panama should prioritize structural changes, improving essential infrastructure, and strengthening its labor rules. Also, Panama will need to intensify its focus on institutional reforms. It should reduce long-term disparities in human capital and close gender gaps, support a more inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic recovery, and address institutional weaknesses for building a stronger and fiscally sustainable economy.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the effect of the release of the Panama Papers in 2016 was dramatic and is still present in the Panamanian economy today. Regardless, it prompted necessary anticorruption measures, which in the long-term, will only continue to strengthen the economy and financial system. The continuation of the reforms discussed above in conjunction with the other measures and investments Panama can take to continue to support its economy will help Panama re-assert its position in the global economy.

By Sara D’Apice, Francesco Doga, Matilde Oliana, Mihály Schieszler

SOURCES

- AML Intelligence

- BBC

- COFACE: Economic Study on Panama

- Direkt36 (non-profit investigative journalism center)

- Economist Intelligence Unit “Panama Economy, Politics and GDP Growth Summary"

- The Guardian

- International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ)

- International Monetary Fund

- International Relocation Firm, “How Panama Built its Way into an Economic and Trade Hub”

- Investopedia, “Why is Panama considered a Tax Haven”

- Mossack Fonseca

- Spiegel

- The World Bank