In the last decade, China has increasingly become the biggest investor in renewable energies and the biggest market for electric vehicles. Investment in renewables capacity worldwide was $282.2 billion last year, up 1% from 2018 $280.2 billion, and China, although it saw an 8% fall compared to the amount in 2018, remained at the top of the list. The country is the greenest in the world, since it has more solar and wind plants than anybody else, but also the most polluting, with increasing numbers of new coal plants being built. That’s why the Chinese government has aggressively favored the shift towards electric vehicles. It wants to be the frontrunner in such a market that, according to analysts, is estimated to grow globally from 3,269,671 units in 2019 to 26,951,318 units by 2030, at a CAGR of 21.1%. However, the government’s goals could be severely jeopardized by recent disruptions caused by the coronavirus outbreak and the crash in oil prices.

The situation prior to the turmoil

China wants new energy vehicles to make up a fifth of its auto sales by 2025, and the government has outlined a goal of reaching 7 million in annual sales for those vehicles by that year. To that end, the Chinese government has spent more than $60 billion in the last few years to support the electric-car industry, including research-and-development funding, generous government subsidies, tax exemptions and financing for battery-charging stations, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This encouraged a stunning number of firms to enter this market, bringing the overall number of manufacturers of new energy vehicles to 486, as of March 2019.

However, after several years of booming electric-car sales, mainly driven by the government subsidies offered to the buyers, the government trimmed subsidies last July. Authorities had to intervene in what had become an overcrowded field and made it less reliant on state support. This caused a significant decrease in demand, and sales of new energy cars fell 4% year-on-year to 1.2m last year, far below the official target of 1.6m. These numbers were also the result of a slowing economy (as the country’s increase in GDP fell to 6%, the lowest level in 30 years) combined with the ongoing trade war with the US.

Considering the entire car market, the world’s biggest one is entering in 2020 into its third year of shrinking sales after reversing for the first time in 2018 since 1990. The fall in sales was 8.2% to 25.8m vehicles in 2019. This followed a 2.8% fall to 28.1m in 2018 compared with the previous year, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

The situation prior to the turmoil

China wants new energy vehicles to make up a fifth of its auto sales by 2025, and the government has outlined a goal of reaching 7 million in annual sales for those vehicles by that year. To that end, the Chinese government has spent more than $60 billion in the last few years to support the electric-car industry, including research-and-development funding, generous government subsidies, tax exemptions and financing for battery-charging stations, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies. This encouraged a stunning number of firms to enter this market, bringing the overall number of manufacturers of new energy vehicles to 486, as of March 2019.

However, after several years of booming electric-car sales, mainly driven by the government subsidies offered to the buyers, the government trimmed subsidies last July. Authorities had to intervene in what had become an overcrowded field and made it less reliant on state support. This caused a significant decrease in demand, and sales of new energy cars fell 4% year-on-year to 1.2m last year, far below the official target of 1.6m. These numbers were also the result of a slowing economy (as the country’s increase in GDP fell to 6%, the lowest level in 30 years) combined with the ongoing trade war with the US.

Considering the entire car market, the world’s biggest one is entering in 2020 into its third year of shrinking sales after reversing for the first time in 2018 since 1990. The fall in sales was 8.2% to 25.8m vehicles in 2019. This followed a 2.8% fall to 28.1m in 2018 compared with the previous year, according to the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

Figures from the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers, released in October 2019, showed that sales of new energy vehicles, which include both hybrid and electric cars, were down 45.6% compared to the same month in the previous year, which were at about 75,000 units. This result is really important, because it marks the fourth straight month of contraction in China’s NEV market and follows a 33% decline in September.

China aims at eventually banning petrol and diesel vehicles, and in order to achieve this goal, the increase of the number of EV in the country is a must. Nevertheless, the country’s market for clean-energy vehicles, the world’s biggest, has faded after some subsidies intended to lure first-time buyers were phased out last July. The latter has exacerbated the already difficult situation of some Chinese NEV makers. Shares in Nio, once considered the country’s answer to Tesla, have dropped 70% over the past year as vehicle deliveries missed expectations. The company made a $479m loss in its most recent quarter.

This slump in the electric vehicle market made the central government decide in January to maintain the remaining subsidies in place, instead of eliminating them in July, as it was previously planned. Subsidies that are now available to customers lower a vehicle’s cost by as much as 25,000 yuan ($3500), depending on the driving range. Prolonging the handouts will help out local EV makers such as BYD Co., BAIC BluePark New Energy Technology Co. and NIO Inc. as well as firms like Tesla Inc., which in January started deliveries from its new Shanghai giga-factory, its first outside the U.S.

It’s clear that China wanted to carry on with its goal of being the frontrunner in this market, but, with the disruptions caused by the coronavirus and the fall in oil prices, will this goal remain unchanged?

Coronavirus and Oil Shock

The outbreak of the virus wreaked havoc in what had been the longest bull market in history. Countries all over the world have recently quarantined its citizens and the economy has been brought to a standstill. The pandemic disrupted the supply chains all over the world, and China, the biggest exporter globally, came under intense strain. Of course, the auto industry is not an exception. China car sales plunged 92% during the first two weeks of February, according to the China Passenger Car Association.

China aims at eventually banning petrol and diesel vehicles, and in order to achieve this goal, the increase of the number of EV in the country is a must. Nevertheless, the country’s market for clean-energy vehicles, the world’s biggest, has faded after some subsidies intended to lure first-time buyers were phased out last July. The latter has exacerbated the already difficult situation of some Chinese NEV makers. Shares in Nio, once considered the country’s answer to Tesla, have dropped 70% over the past year as vehicle deliveries missed expectations. The company made a $479m loss in its most recent quarter.

This slump in the electric vehicle market made the central government decide in January to maintain the remaining subsidies in place, instead of eliminating them in July, as it was previously planned. Subsidies that are now available to customers lower a vehicle’s cost by as much as 25,000 yuan ($3500), depending on the driving range. Prolonging the handouts will help out local EV makers such as BYD Co., BAIC BluePark New Energy Technology Co. and NIO Inc. as well as firms like Tesla Inc., which in January started deliveries from its new Shanghai giga-factory, its first outside the U.S.

It’s clear that China wanted to carry on with its goal of being the frontrunner in this market, but, with the disruptions caused by the coronavirus and the fall in oil prices, will this goal remain unchanged?

Coronavirus and Oil Shock

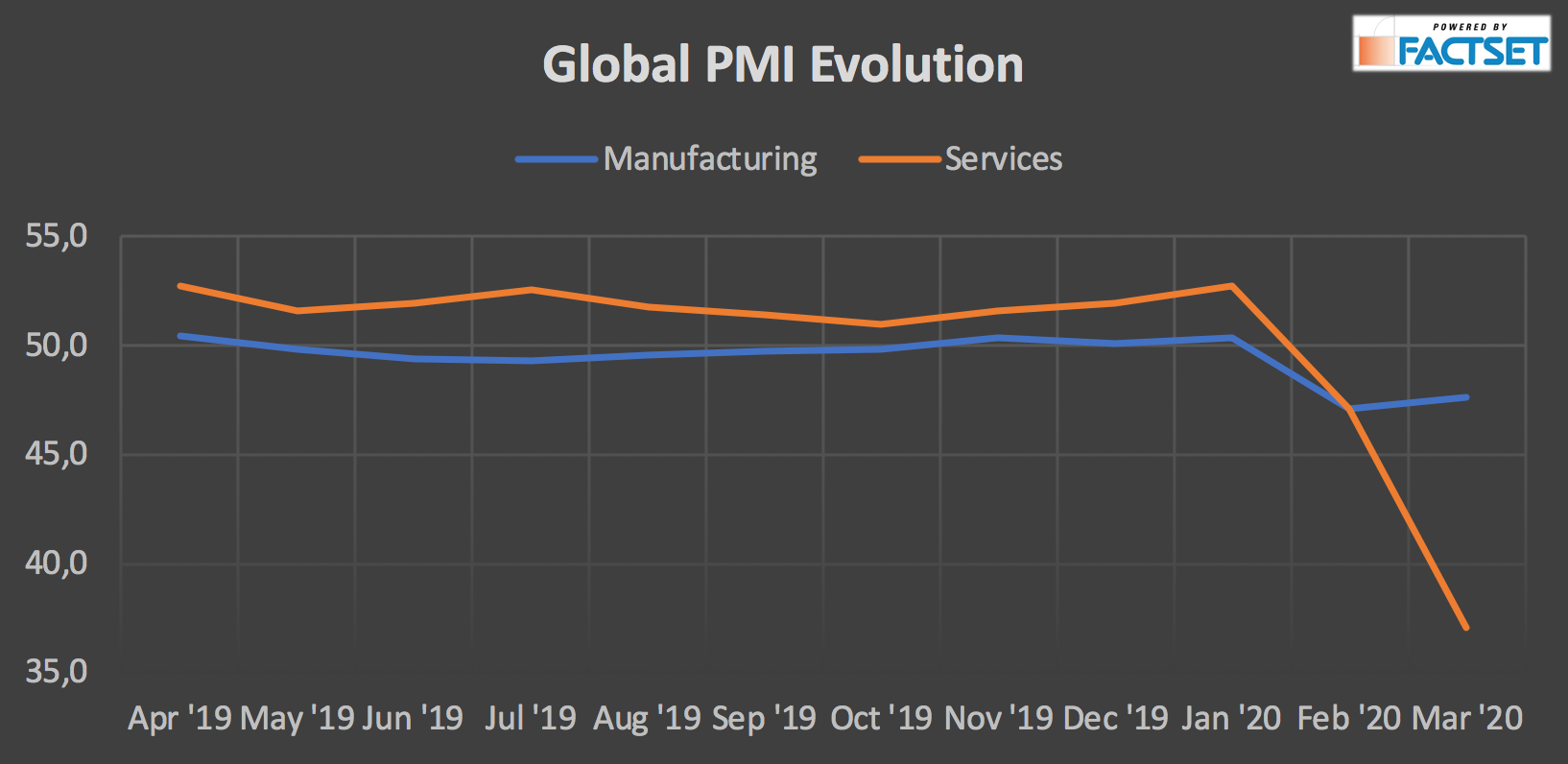

The outbreak of the virus wreaked havoc in what had been the longest bull market in history. Countries all over the world have recently quarantined its citizens and the economy has been brought to a standstill. The pandemic disrupted the supply chains all over the world, and China, the biggest exporter globally, came under intense strain. Of course, the auto industry is not an exception. China car sales plunged 92% during the first two weeks of February, according to the China Passenger Car Association.

This year, the world’s largest car market was expected to bounce back, after 2 years of falling sales. However, this hope vanished in February, with analysts predicting that the coronavirus will lead China into its third consecutive year of shrinking sales. Electric vehicle manufacturers were still trying to recover from subsidy cuts, and even before the coronavirus became a pandemic, the number sold plummeted 54% in January.

While most carmakers have reopened their plants in China, the effects of the coronavirus are still clearly present. Even though the employees went back to work, firms are now facing another huge problem: lack of production components from the supply chain. China’s electric vehicle start-ups, already busy in dealing with the end of a venture capital boom and a decreasing demand, are now required to face parts shortages and empty car shops. This situation could cause some of them to default. Plummeting oil prices are exacerbating an already difficult reality, making the switch to electric vehicles less appealing to price-sensitive Chinese buyers.

On March 18, oil prices fell to their lowest level in 17 years, dropping below $25 a barrel. The demand for fuel has been hit by travel restrictions introduced in some of the world’s biggest economies, as they try to contain the spread of the coronavirus. In addition to this decreasing demand, there’s also the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, with both of them declaring that they will ramp up the daily production of oil.

While most carmakers have reopened their plants in China, the effects of the coronavirus are still clearly present. Even though the employees went back to work, firms are now facing another huge problem: lack of production components from the supply chain. China’s electric vehicle start-ups, already busy in dealing with the end of a venture capital boom and a decreasing demand, are now required to face parts shortages and empty car shops. This situation could cause some of them to default. Plummeting oil prices are exacerbating an already difficult reality, making the switch to electric vehicles less appealing to price-sensitive Chinese buyers.

On March 18, oil prices fell to their lowest level in 17 years, dropping below $25 a barrel. The demand for fuel has been hit by travel restrictions introduced in some of the world’s biggest economies, as they try to contain the spread of the coronavirus. In addition to this decreasing demand, there’s also the price war between Saudi Arabia and Russia, with both of them declaring that they will ramp up the daily production of oil.

With fossil fuel prices falling, some analysts fear that governments will reduce their spending on renewable projects in favor of cheap oil and gas. If, on the one hand, the EU is predicted to push ahead with its renewable energy investment, on the other hand, China and India are facing increasing demands for energy, and for this reason they are likely to be tempted to lock in favorable prices from Saudi Arabia and Russia for fuel.

At least in the short term, the coronavirus outbreak and the oil meltdown will cause disruptions in China’s plans for the future of electric vehicles in the country. Nevertheless, the long-term growth prospects of the electric vehicles industry remain solid, with analysts bullish on both clean energies and EVs.

For clean vehicles, cheap oil is believed to delay price parity between electric cars and fossil-fuel vehicles by a year or two. But eventually decreasing costs in renewables and increasing climate change awareness will certainly lead to an extraordinary growth in EVs.

Antonio Wang

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here

At least in the short term, the coronavirus outbreak and the oil meltdown will cause disruptions in China’s plans for the future of electric vehicles in the country. Nevertheless, the long-term growth prospects of the electric vehicles industry remain solid, with analysts bullish on both clean energies and EVs.

For clean vehicles, cheap oil is believed to delay price parity between electric cars and fossil-fuel vehicles by a year or two. But eventually decreasing costs in renewables and increasing climate change awareness will certainly lead to an extraordinary growth in EVs.

Antonio Wang

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here