As Europe faces up the fight against Covid-19 and the danger of a new crisis grows, the discussion about the introduction of new economic instruments in order to deal with the consequences of the epidemic intensifies. In particular, nine European leaders are strongly calling for the emission of ‘Corona bonds’ (resuming the idea of Eurobonds), as a new collective response to the emergency.

The Pro-bonds and their arguments

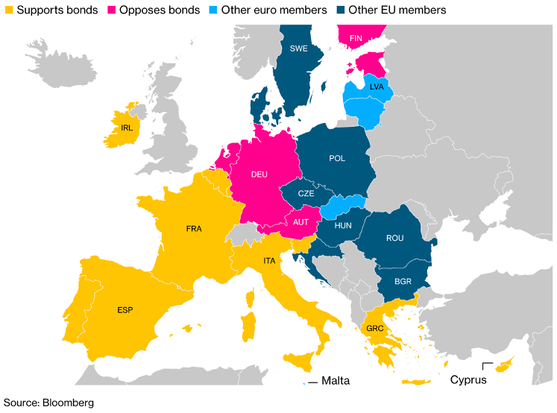

Nine EU countries are currently sustaining the introduction of the ‘corona bonds’: Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Slovenia.

Some of these, like Italy and Spain, have been heavily hit by Covid-19 with thousands of deaths and struggling to finance their healthcare and social costs, exposing the inequality between the EU members like never before. For this reason, the European Central Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) may be not sufficient to sustain these economies and might erode European unity and solidity.

"If we don’t propose now a unified, powerful and effective response to this economic crisis, not only the impact will be tougher, but its effects will last longer and we will be putting at risk the entire European project," says Sánchez, Prime Minister of Spain "The same mistakes of the financial crisis of 2008 — which sowed the seeds of disaffection and division with the European project, and provoked the rise of populism — cannot be made. We must learn that lesson."

Being in the centre of the discussion between EU leaders since 1999 and previously known as Euro bonds, they are a common debt instrument to finance borrowing, where the money would be headed to the countries that most need them. They would be issued from the European Investment Bank.

The proposal is for a jointly backed bond sale of up to 1.5 trillion euros that would fund government initiatives to contain the virus and boost euro-area economies.

Therefore, the emission of ‘Corona bonds’ would be a crucial political and economic move for different reasons.

An advantage of this proposal is that the bonds would constitute supranational debt, so they wouldn’t contribute to national debt levels, even if governments would have contingent liability through their capital shares in the EIB. These bonds could be eventually acquired by the ECB, providing coordination between monetary and fiscal policy.

In addition, it would allow a heavy and joint response to a shared crisis, helping avoid the danger of a financial crisis after the end of austerity.

Their introduction would then demonstrate European solidarity and compactness which has been high challenged by the current emergency, both by member states and by countries outside the eurozone,. Many have in fact pointed out the fundamental need of greater economic cooperation, especially within EU, since when Italy, so far the country that suffered the most from the virus in the continent, begged for urgent assistance and none of the other 26 EU governments responded – until China eventually did.

Finally, more broadly, the ‘Corona bond’ would eventually represent a safe asset for European and international investors.

Overall, such a bond would serve the purposes of helping to finance the costs of the crisis and sending a strong signal to markets, firms and citizens that Europe is united and working for the benefit of all.

Who is on the other side?

The ‘moral hazard’ argument, since the first idea of a Eurobond, has been a strong roadblock from the richer countries like Germany, Austria and the Netherlands who considered this as an encouragement to further irresponsible behaviour.

Also this time, during the last EU virtual summit (27th March), despite the emergency has not been caused by bad spending but by an unpredictable global health crisis, these countries have strongly opposed the emission of such bonds.

These visions have been made clear by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, sustained by the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz and Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin. “You are aware of the letters from some member states who have imagined or are imagining corona bonds,” she told reporters. “We have said from both the German and other sides that this is not ... the view of all EU countries.”

The Pro-bonds and their arguments

Nine EU countries are currently sustaining the introduction of the ‘corona bonds’: Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Luxembourg, Ireland, Portugal, Greece and Slovenia.

Some of these, like Italy and Spain, have been heavily hit by Covid-19 with thousands of deaths and struggling to finance their healthcare and social costs, exposing the inequality between the EU members like never before. For this reason, the European Central Bank’s Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP) may be not sufficient to sustain these economies and might erode European unity and solidity.

"If we don’t propose now a unified, powerful and effective response to this economic crisis, not only the impact will be tougher, but its effects will last longer and we will be putting at risk the entire European project," says Sánchez, Prime Minister of Spain "The same mistakes of the financial crisis of 2008 — which sowed the seeds of disaffection and division with the European project, and provoked the rise of populism — cannot be made. We must learn that lesson."

Being in the centre of the discussion between EU leaders since 1999 and previously known as Euro bonds, they are a common debt instrument to finance borrowing, where the money would be headed to the countries that most need them. They would be issued from the European Investment Bank.

The proposal is for a jointly backed bond sale of up to 1.5 trillion euros that would fund government initiatives to contain the virus and boost euro-area economies.

Therefore, the emission of ‘Corona bonds’ would be a crucial political and economic move for different reasons.

An advantage of this proposal is that the bonds would constitute supranational debt, so they wouldn’t contribute to national debt levels, even if governments would have contingent liability through their capital shares in the EIB. These bonds could be eventually acquired by the ECB, providing coordination between monetary and fiscal policy.

In addition, it would allow a heavy and joint response to a shared crisis, helping avoid the danger of a financial crisis after the end of austerity.

Their introduction would then demonstrate European solidarity and compactness which has been high challenged by the current emergency, both by member states and by countries outside the eurozone,. Many have in fact pointed out the fundamental need of greater economic cooperation, especially within EU, since when Italy, so far the country that suffered the most from the virus in the continent, begged for urgent assistance and none of the other 26 EU governments responded – until China eventually did.

Finally, more broadly, the ‘Corona bond’ would eventually represent a safe asset for European and international investors.

Overall, such a bond would serve the purposes of helping to finance the costs of the crisis and sending a strong signal to markets, firms and citizens that Europe is united and working for the benefit of all.

Who is on the other side?

The ‘moral hazard’ argument, since the first idea of a Eurobond, has been a strong roadblock from the richer countries like Germany, Austria and the Netherlands who considered this as an encouragement to further irresponsible behaviour.

Also this time, during the last EU virtual summit (27th March), despite the emergency has not been caused by bad spending but by an unpredictable global health crisis, these countries have strongly opposed the emission of such bonds.

These visions have been made clear by the German Chancellor Angela Merkel, sustained by the Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte, Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz and Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin. “You are aware of the letters from some member states who have imagined or are imagining corona bonds,” she told reporters. “We have said from both the German and other sides that this is not ... the view of all EU countries.”

In general, the introduction of ‘Corona bonds’ has certainly different advantages, but it is also accompanied by some considerations and amendments.

Firstly, they would need to be structured in order to be targeted to the specific purpose of a pandemic fight and limited to a case of extreme emergency.

Then, the bonds would require a high rating, which might necessitate a capital increase of the issuing institution and a strong centralized budget. This is a function that could be entrusted to ESM, but its resources are too limited and the conditions too drastic. This implies the creation of another form of federal budget or an adjustment of the actual structure of the ESM, both steps that would require greater agreements and political centralization.

The solution, in order to avoid the problem of the guarantees, would be the purchase of the ‘Corona bonds’ by the ECB directly at issuance. But this is currently not legally possible as the article 21 of the statutes of ECB prohibits the acquisition of government bonds on the primary market.

To sum up the problem of the guarantees of ‘Corona bonds’ would not be so consistent if they were issued to finance investment, like infrastructure, that would directly represent the guarantees, rather than current expenditure. In fact, they cannot be issued to it, unless adequate means and guarantees are brought under the control of EU.

So, even if a euro ‘corona bond’ would surely send a strong supportive signal to the weakest European countries when confronted by a common shock and it would be more powerful than monetary policy contortions in restoring economic confidence, it would probably require a long time and some relevant amendments to be able to achieve its objective.

Are there any alternatives?

The alternative option, sustained by Merkel, is the use of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), created during 2012, which provides financial help in form of loans to European countries and banks in difficulty.

"With the ESM we have a crisis instrument that opens up many possibilities for us that do not call into question the basic principles of our common and responsible action," she said.

But even if his mechanism would have the advantages of a lower cost of borrowing and lower risk of illiquidity, it introduces different political and economic problems.

Firstly, ESM conditionality would have to be modified and the stigma related to signing up such a programme would have to be reduced.

In fact, it can allow loans only on the basis of an adjustment programme agreed with the European institutions, which carries a range of conditions. For this reason, if just a few countries apply to ESM, it would increase the inequality between EU members. Respecting the conditions can translate in an increased fragility on the markets and a loss of sovereignty, even if the crisis is due mainly to exogenous health factors rather than fiscal indiscipline.

There are some possible solutions to this problem. The first one can be found in the proposal by Olivier Blanchard (Blanchard 2020) “in this case, conditionality should be very limited, and easy to define: spend what you must on crisis containment and commit to wind down everything once the crisis is over. Full stop. No stigma”. Basically, the aim is to limit the conditions just to a monitoring of the resources used to address the crisis.

The second one requires all countries to apply to ESM, in order to reduce the stigma. This would be a sign of solidarity especially by those countries who don’t necessarily need ESM. Eventually, also this option can have negative consequences related to reallocation of funds, internal division and can work only if there are no veto players.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the European Union is facing an important political choice, which will have a strong impact on the future and the solidity of the Union itself. What is certain is that the current policy actions are insufficient, and this new type of crisis requires to be fought with new instruments.

Eurobond is not the only option, as there’s not a unique solution. The possibilities are various, they need to be carefully considered and require different strategies and time frames, but what’s fundamental is to act quickly, without losing sight of the importance of solidarity and unity during such a worldwide crisis.

Sara Chiuri

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Firstly, they would need to be structured in order to be targeted to the specific purpose of a pandemic fight and limited to a case of extreme emergency.

Then, the bonds would require a high rating, which might necessitate a capital increase of the issuing institution and a strong centralized budget. This is a function that could be entrusted to ESM, but its resources are too limited and the conditions too drastic. This implies the creation of another form of federal budget or an adjustment of the actual structure of the ESM, both steps that would require greater agreements and political centralization.

The solution, in order to avoid the problem of the guarantees, would be the purchase of the ‘Corona bonds’ by the ECB directly at issuance. But this is currently not legally possible as the article 21 of the statutes of ECB prohibits the acquisition of government bonds on the primary market.

To sum up the problem of the guarantees of ‘Corona bonds’ would not be so consistent if they were issued to finance investment, like infrastructure, that would directly represent the guarantees, rather than current expenditure. In fact, they cannot be issued to it, unless adequate means and guarantees are brought under the control of EU.

So, even if a euro ‘corona bond’ would surely send a strong supportive signal to the weakest European countries when confronted by a common shock and it would be more powerful than monetary policy contortions in restoring economic confidence, it would probably require a long time and some relevant amendments to be able to achieve its objective.

Are there any alternatives?

The alternative option, sustained by Merkel, is the use of the European Stability Mechanism (ESM), created during 2012, which provides financial help in form of loans to European countries and banks in difficulty.

"With the ESM we have a crisis instrument that opens up many possibilities for us that do not call into question the basic principles of our common and responsible action," she said.

But even if his mechanism would have the advantages of a lower cost of borrowing and lower risk of illiquidity, it introduces different political and economic problems.

Firstly, ESM conditionality would have to be modified and the stigma related to signing up such a programme would have to be reduced.

In fact, it can allow loans only on the basis of an adjustment programme agreed with the European institutions, which carries a range of conditions. For this reason, if just a few countries apply to ESM, it would increase the inequality between EU members. Respecting the conditions can translate in an increased fragility on the markets and a loss of sovereignty, even if the crisis is due mainly to exogenous health factors rather than fiscal indiscipline.

There are some possible solutions to this problem. The first one can be found in the proposal by Olivier Blanchard (Blanchard 2020) “in this case, conditionality should be very limited, and easy to define: spend what you must on crisis containment and commit to wind down everything once the crisis is over. Full stop. No stigma”. Basically, the aim is to limit the conditions just to a monitoring of the resources used to address the crisis.

The second one requires all countries to apply to ESM, in order to reduce the stigma. This would be a sign of solidarity especially by those countries who don’t necessarily need ESM. Eventually, also this option can have negative consequences related to reallocation of funds, internal division and can work only if there are no veto players.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the European Union is facing an important political choice, which will have a strong impact on the future and the solidity of the Union itself. What is certain is that the current policy actions are insufficient, and this new type of crisis requires to be fought with new instruments.

Eurobond is not the only option, as there’s not a unique solution. The possibilities are various, they need to be carefully considered and require different strategies and time frames, but what’s fundamental is to act quickly, without losing sight of the importance of solidarity and unity during such a worldwide crisis.

Sara Chiuri

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.