Once again, Argentina is going through a very delicate period. The country has already defaulted 8 times since its independence and now the government is looking for a debt restructuring to avoid a messy default. Moody’s rating for the country stands at Caa2, reflecting “years of unpredictable and unsustainable macroeconomic and fiscal policymaking”.

Argentina is in the middle of a very intense negotiation to set up a debt restructuring. On the one hand, the government is dealing with the IMF to renegotiate the terms of the Stand-By Agreement. At the same time, Argentina is also trying to impose a haircut on bonds held by private creditors. It is not clear what is going to happen, but one thing is certain: Argentina’s debt is not sustainable anymore and the country is still struggling to recover from a very deep recession. Indeed, Debt/GDP ratio reached 94%, inflation is one of the highest in the world at 51%, real GDP is shrinking at an annual rate of -1.3% (Argentina’s GDP is $443.35 Billion), unemployment is above 10% and the Ratio of reserves/ARA metric is 0.79 (it should be above 1).

The 2018 currency crisis:

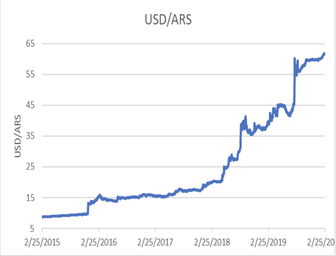

In 2018, Argentina was hit hard by a series of adverse events, such as adverse weather conditions, distress in emerging markets due to the Fed’s adjustment of the interest rate, and a more general change in the market’s perception of the Argentinian economy. These events led to a severe currency crisis: at the beginning of 2018 one US Dollar bought 19 Argentine Peso; at the end of the same year the exchange was above 37 Argentine Peso for US Dollar (today the exchange rate is above 61 Argentine Peso for US Dollar). Argentina signed a deal with the International Monetary Fund and the country was entitled to receive a $57 billion loan. This loan was conditioned to the implementation of some macroeconomic policies aimed at the stabilization of public accounts and to reach a primary fiscal balance.

Argentina is in the middle of a very intense negotiation to set up a debt restructuring. On the one hand, the government is dealing with the IMF to renegotiate the terms of the Stand-By Agreement. At the same time, Argentina is also trying to impose a haircut on bonds held by private creditors. It is not clear what is going to happen, but one thing is certain: Argentina’s debt is not sustainable anymore and the country is still struggling to recover from a very deep recession. Indeed, Debt/GDP ratio reached 94%, inflation is one of the highest in the world at 51%, real GDP is shrinking at an annual rate of -1.3% (Argentina’s GDP is $443.35 Billion), unemployment is above 10% and the Ratio of reserves/ARA metric is 0.79 (it should be above 1).

The 2018 currency crisis:

In 2018, Argentina was hit hard by a series of adverse events, such as adverse weather conditions, distress in emerging markets due to the Fed’s adjustment of the interest rate, and a more general change in the market’s perception of the Argentinian economy. These events led to a severe currency crisis: at the beginning of 2018 one US Dollar bought 19 Argentine Peso; at the end of the same year the exchange was above 37 Argentine Peso for US Dollar (today the exchange rate is above 61 Argentine Peso for US Dollar). Argentina signed a deal with the International Monetary Fund and the country was entitled to receive a $57 billion loan. This loan was conditioned to the implementation of some macroeconomic policies aimed at the stabilization of public accounts and to reach a primary fiscal balance.

Source: Investing.com

From the currency crisis to the past summer:

The IMF’s loan helped to stabilize the exchange rate and the situation seemed under control. However, some downside risk remained. For instance, in the Fourth Review under the Stand-By-Arrangement the IMF team pointed out some crucial issues:

The current negotiation:

In February, Julie Kozack, Deputy Director of the Western Hemisphere Department at the IMF, together with her team visited Buenos Aires to strike a deal with the local government. At the end of this period, the IMF released a statement in which they stressed two key points. First, Argentina’s economy has deteriorated considerably since July 2019 (date of the previous Debt Sustainability Analysis) and the country’s debt load is not sustainable any longer. Second, the austerity measures needed to achieve a primary surplus, which would allow reducing public debt, are not economically nor politically feasible. To some degree, the IMF seemed to endorse the position of the current Argentinian economy minister, Martìn Guzmàn, who had previously said that the government will not try to balance its budget until 2023 at the earliest. Finally, the IMF called for a “definite debt operation” to restore debt sustainability. In other words, a haircut on Government bonds which will hit private creditors. The latter are invited to join a “collaborative” negotiation to reach the approval of a debt restructuring.

Nevertheless, the statement does not clarify future developments between the IMF and Argentina. This is not a minor point since the IMF is the major creditor of the country. Indeed, Argentina has already received $44bn out of the $57bn accorded in the bailout plan signed during the currency crisis in 2018 (notice that most of the funds had already been distributed during the former presidency, reducing the influence that the IMF has on the current government led by Alberto Fernández). Moreover, Kristalina Georgieva, the current IMF’s Managing Director, said that Argentina is expected to pay back in full the emergency loan provided by the Washington-based fund. This statement was in response to a comment by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina’s vice-president, who said that also the IMF shall suffer a “substantial” haircut. The government set the March 31st as a self-imposed deadline to solve the debt crisis and, since it is not likely that private creditors will accept a 40-50% haircut, then the IMF may play a crucial role in the negotiation.

After the announcement by the IMF, Argentinian bonds plunged, with the bond maturing in 2021 trading at 53 cents on the dollar. The $2.75bn US dollar-denominated bond with an initial 100-year maturity (launched in 2017) is now trading at 43 cents on the dollar (at the beginning of 2019 was traded at more than 50 cents). Finally, bonds maturing in 2028 trades at 45 cents.

What’s next?

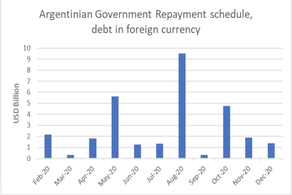

Analyzing the debt repayment schedule for 2020, the Argentinian government must pay $26bn to private creditors, of which $22.13bn are under the national jurisdiction and 4.16bn under foreign law. Notice that the latter are consistently traded at a premium with respect to bonds underwritten under the national law. Moreover, there are also $3.7bn to be paid to international financial institutions and $2.4bn of previously restructured debt. The most critical phase would be in August, with the maturity of $9bn of LETES (Letras del Tesoro de la Nación) initially maturing in December 2019 and subsequently delayed to August 2020. Given the current level of Net Reserves, amounting to $45bn, the government should be able to cover the entire debt service. Nevertheless, regional entities may absorb part of the liquidity.

The IMF’s loan helped to stabilize the exchange rate and the situation seemed under control. However, some downside risk remained. For instance, in the Fourth Review under the Stand-By-Arrangement the IMF team pointed out some crucial issues:

- High rollover risk since Argentina had financed itself with new short-term maturities.

- Given the large share of the public debt denominated in foreign currency, the debt trajectory was particularly exposed to adverse exchange rate movements.

- The country had large external financing needs.

The current negotiation:

In February, Julie Kozack, Deputy Director of the Western Hemisphere Department at the IMF, together with her team visited Buenos Aires to strike a deal with the local government. At the end of this period, the IMF released a statement in which they stressed two key points. First, Argentina’s economy has deteriorated considerably since July 2019 (date of the previous Debt Sustainability Analysis) and the country’s debt load is not sustainable any longer. Second, the austerity measures needed to achieve a primary surplus, which would allow reducing public debt, are not economically nor politically feasible. To some degree, the IMF seemed to endorse the position of the current Argentinian economy minister, Martìn Guzmàn, who had previously said that the government will not try to balance its budget until 2023 at the earliest. Finally, the IMF called for a “definite debt operation” to restore debt sustainability. In other words, a haircut on Government bonds which will hit private creditors. The latter are invited to join a “collaborative” negotiation to reach the approval of a debt restructuring.

Nevertheless, the statement does not clarify future developments between the IMF and Argentina. This is not a minor point since the IMF is the major creditor of the country. Indeed, Argentina has already received $44bn out of the $57bn accorded in the bailout plan signed during the currency crisis in 2018 (notice that most of the funds had already been distributed during the former presidency, reducing the influence that the IMF has on the current government led by Alberto Fernández). Moreover, Kristalina Georgieva, the current IMF’s Managing Director, said that Argentina is expected to pay back in full the emergency loan provided by the Washington-based fund. This statement was in response to a comment by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, Argentina’s vice-president, who said that also the IMF shall suffer a “substantial” haircut. The government set the March 31st as a self-imposed deadline to solve the debt crisis and, since it is not likely that private creditors will accept a 40-50% haircut, then the IMF may play a crucial role in the negotiation.

After the announcement by the IMF, Argentinian bonds plunged, with the bond maturing in 2021 trading at 53 cents on the dollar. The $2.75bn US dollar-denominated bond with an initial 100-year maturity (launched in 2017) is now trading at 43 cents on the dollar (at the beginning of 2019 was traded at more than 50 cents). Finally, bonds maturing in 2028 trades at 45 cents.

What’s next?

Analyzing the debt repayment schedule for 2020, the Argentinian government must pay $26bn to private creditors, of which $22.13bn are under the national jurisdiction and 4.16bn under foreign law. Notice that the latter are consistently traded at a premium with respect to bonds underwritten under the national law. Moreover, there are also $3.7bn to be paid to international financial institutions and $2.4bn of previously restructured debt. The most critical phase would be in August, with the maturity of $9bn of LETES (Letras del Tesoro de la Nación) initially maturing in December 2019 and subsequently delayed to August 2020. Given the current level of Net Reserves, amounting to $45bn, the government should be able to cover the entire debt service. Nevertheless, regional entities may absorb part of the liquidity.

Source: Ministerio de Economía

For what concerns negotiations between Argentina and IMF, it is hard to forecast what is going to happen. Most likely, there may be a trade-off between the economic reforms required from the IMF to restart the program and the haircut imposed to investors: the greater the austerity, the higher the haircut. Finally, the spread of Coronavirus and the consequent slowdown of the global economy are not going to help Argentina to recover from the economic recession.

Marco Calamandrei.

Sources:

Financial Times, Bloomberg,World Bank’s web site, IMF’s web site, Moody’s, Ministerio de Economía – Gobierno de Argentina, Sole 24 ore

Marco Calamandrei.

Sources:

Financial Times, Bloomberg,World Bank’s web site, IMF’s web site, Moody’s, Ministerio de Economía – Gobierno de Argentina, Sole 24 ore