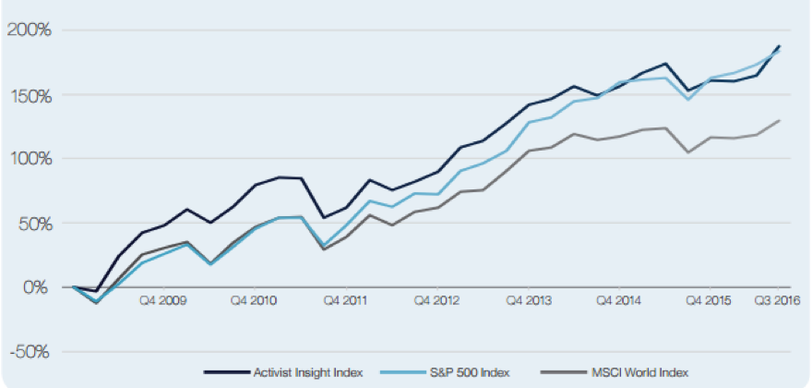

On the eve of Enron’s scandal’s fifteenth anniversary, the “Common sense Principles of Corporate Governance” for U.S. public companies urge further discussion on Corporate Governance issues worldwide, with the ultimate aim of stimulating economic growth. The increasingly influential role of asset managers activism on these purposes even led US authorities to dedicate them and Principle VIII “Asset Managers’ Role in Corporate Governance”. As a matter of fact, activist asset managers are now very common in the US and their intrusion seems to add to companies’ performances.

Compounded Activist Insight Index versus S&P 500 and MSCI World indices - Source: Schulte Roth and Zabel LLP Annual Report on Activist Investors

Not only do asset managers undeniably have the power to influence the governance practices, but they are also expected to exercise it with the purpose of achieving long term value. As a matter of fact, asset managers act on behalf of a great number of people who expect to benefit from their investments over a long time frame. It can be argued that traditional asset managers measure the effectiveness of their portfolio by focusing on the either spot or short term performance compared to the market. This way, their investment strategy can be simplified in buying undervalued shares and selling overvalued ones. Nevertheless, the VIII Principle asks traditionalists to make the effort to change view in running their business. Asset managers are supposed to unveil under-priced stocks issued by firms which in fact have potential. Thereon, they should engage actively in removing market scepticism not only by exerting their votes, but also and more importantly by establishing a robust dialogue with managers on both corporate governance and corporate strategy issues. As a result of more balanced and carefully evaluated decisions, the firm would be more performing and, ultimately, corporate managers, individual shareholders and asset managers and would be better off. On the one hand, managers would benefit from higher performance related compensation. On the other hand, both individual shareholders and asset managers would be able to liquidate their position and make a capital gain, if they wanted to. This brings me to the other side of the coin. Implementing an effective activism would require traditional asset management firms to attract a broader range of professional skills, for instance by hiring strategic consultants and accountants. Moreover, assuming that they eventually manage to enhance corporate performances, they would only benefit from a small stake of the enhancement itself, despite having borne the costs of their activism. Therefore, I believe that governments should impose specific regulations so that the free riding problem would not discourage shareholders’ activism. In particular, firms should facilitate dialogue with any wannabe activists shareholders, while ensuring that collecting information is less costly as possible for all shareholders.

As for the UK Corporate Governance Principles for listed companies, section E is dedicated to the constructive use of general meetings and the main principles states that “the board should use general meetings to communicate with investors and to encourage their participation”. In sharp contrast with the newly issued Common-sense US Corporate Governance principles, throughout the document no specific mention of asset management firms’ peculiar position is made. Probably, the evolution of the role of asset management firms is still at an early stage. However, a soft form of asset managers’ activism has become more common in the UK rather than in the US (7,5% versus 0,5%, respectively). According to an anecdote, in summer 2014 Marty Lipton booked a flight from New York to London so as to warn some corporate clients against the intrusive activism of US hedge funds towards US companies, fearing that European corporations would be the next in their sights. According to Lipton, this attitude would not lead to any improvement for firms in difficult situations as their priority would be cost restructuring and divestments. Two years later, in turned out that Lipton was right in foreseeing an enhanced activism in Europe as well, but his negative outlook was unjustified.

As a matter of fact, US asset managers’ have not yet broke into the European world. European asset managers have established and are working on improving the dialogue with corporations, among which there are Volkswagen, Adidas, Rolls-Royce, Alliance Trust and NH Hotels. Apparently, what differentiates the formers from their overseas colleagues is the style of activism. European asset managers seem to opt for a more diplomatic approach that leads to corporations’ eagerness to cooperate, rather than to a defensive reaction. In the light of these considerations, I would conclude that the sensitization of asset managers activism is taking place in Europe in a sound and natural way and this might well be the reason for its lack of mention in the UK Corporate Governance Principles. The VII Common Sense Corporate Governance principles for listed companies in the US outlines the importance of crafting a compensation scheme in order to align the interests of managers and owners. While in the US it is mentioned that managerial performance should be measured along a variety of indicators, including for instance openness and integrity, in the UK there is no reference to qualitative metrics.

I think that the American emphasis on soft metrics should be put also in the UK Code. Linking the CEO’s pay merely on quantitative metrics, could more likely than not provide incentives to engage in non-value creating M&A deals. In has been shown by some researchers that CEOs’ M&A bonuses are often explained by compensations committees with reference to the increase in the size of the firm, rather than on the strategic soundness of the deal. As a result, compensating CEOs by the yardsticks of revenue and asset size could lead to them to excessive valuations and deal fever pitfalls, whose side effect would be mostly borne by shareholders. Although some people argue that compensating managers by stock options would solve this issue, there are still two main obstacles. Firstly, M&A bonuses are in practice paid by cash and they are supported by formula based explanations rather than strategic analysis. Secondly, since nowadays markets are characterized by high uncertainty due to the macroeconomic shocks, it would be difficult to define appropriate strike prices for the options. Consequently, managers would fear higher interest rates would drive down share prices, thus ending up with out of the money options. All in all, I feel that the inclusion of soft metrics in managers’ compensation would smoothen this effect. Additionally, consistently with the above mentioned issues on shareholders’ activism, I believe asset managers could have the power to contain CEOs’ strategically unjustified shopping sprees as well as to urge spin offs when two branches of a company no longer have synergies. In conclusion, I feel that asset managers’ activism is already settling in the UK, and in a healthier way. No sooner more companies appreciate the win-win outcomes of their cooperation with asset managers, than a virtuous circle will sparkle off, luring the other European countries to follow the British beaten track.

Irene Pilla

As for the UK Corporate Governance Principles for listed companies, section E is dedicated to the constructive use of general meetings and the main principles states that “the board should use general meetings to communicate with investors and to encourage their participation”. In sharp contrast with the newly issued Common-sense US Corporate Governance principles, throughout the document no specific mention of asset management firms’ peculiar position is made. Probably, the evolution of the role of asset management firms is still at an early stage. However, a soft form of asset managers’ activism has become more common in the UK rather than in the US (7,5% versus 0,5%, respectively). According to an anecdote, in summer 2014 Marty Lipton booked a flight from New York to London so as to warn some corporate clients against the intrusive activism of US hedge funds towards US companies, fearing that European corporations would be the next in their sights. According to Lipton, this attitude would not lead to any improvement for firms in difficult situations as their priority would be cost restructuring and divestments. Two years later, in turned out that Lipton was right in foreseeing an enhanced activism in Europe as well, but his negative outlook was unjustified.

As a matter of fact, US asset managers’ have not yet broke into the European world. European asset managers have established and are working on improving the dialogue with corporations, among which there are Volkswagen, Adidas, Rolls-Royce, Alliance Trust and NH Hotels. Apparently, what differentiates the formers from their overseas colleagues is the style of activism. European asset managers seem to opt for a more diplomatic approach that leads to corporations’ eagerness to cooperate, rather than to a defensive reaction. In the light of these considerations, I would conclude that the sensitization of asset managers activism is taking place in Europe in a sound and natural way and this might well be the reason for its lack of mention in the UK Corporate Governance Principles. The VII Common Sense Corporate Governance principles for listed companies in the US outlines the importance of crafting a compensation scheme in order to align the interests of managers and owners. While in the US it is mentioned that managerial performance should be measured along a variety of indicators, including for instance openness and integrity, in the UK there is no reference to qualitative metrics.

I think that the American emphasis on soft metrics should be put also in the UK Code. Linking the CEO’s pay merely on quantitative metrics, could more likely than not provide incentives to engage in non-value creating M&A deals. In has been shown by some researchers that CEOs’ M&A bonuses are often explained by compensations committees with reference to the increase in the size of the firm, rather than on the strategic soundness of the deal. As a result, compensating CEOs by the yardsticks of revenue and asset size could lead to them to excessive valuations and deal fever pitfalls, whose side effect would be mostly borne by shareholders. Although some people argue that compensating managers by stock options would solve this issue, there are still two main obstacles. Firstly, M&A bonuses are in practice paid by cash and they are supported by formula based explanations rather than strategic analysis. Secondly, since nowadays markets are characterized by high uncertainty due to the macroeconomic shocks, it would be difficult to define appropriate strike prices for the options. Consequently, managers would fear higher interest rates would drive down share prices, thus ending up with out of the money options. All in all, I feel that the inclusion of soft metrics in managers’ compensation would smoothen this effect. Additionally, consistently with the above mentioned issues on shareholders’ activism, I believe asset managers could have the power to contain CEOs’ strategically unjustified shopping sprees as well as to urge spin offs when two branches of a company no longer have synergies. In conclusion, I feel that asset managers’ activism is already settling in the UK, and in a healthier way. No sooner more companies appreciate the win-win outcomes of their cooperation with asset managers, than a virtuous circle will sparkle off, luring the other European countries to follow the British beaten track.

Irene Pilla