The global payment landscape is rapidly evolving, reflecting in significant changes in households and firms’ preferences. Following this path of technological innovation, countries such as Australia, which already benefit from a modern and well-functioning electronic payment system, have begun to consider the potential benefits - and risks - that tokenization of currency, in the form of a central bank digital currency (CBDC) could bring about for the whole financial system. In this article, within the context of Australia’s recent development, we take a look at the state of CBDC implementations around the world and explore the potential benefits and risks that the technology would have on national economies.

What is tokenization and why is it important

Tokenization is the act of issuing a digital representation of the underlying asset on a blockchain. A blockchain is a system in which a record of transactions is maintained across computers that are linked to a peer-to-peer network. Tokenized assets can include physical assets like real estate or art, financial assets like equities or bonds, intangible assets like intellectual property, or even identity and data. One of the most well-known types of tokenized assets is cryptocurrency.

Tokenization of assets will provide a vast array of benefits some of which will be lower transaction costs, greater access to private markets, and enhanced transaction speed. Regarding private markets for example, they are typically thought of as opaque, inefficient, and difficult to access for the average retail investor, which is exactly why they present a strong use case for tokenization. Many investors remain underweight in private assets due to factors like high minimum investments, long lockup periods, relative illiquidity, and cumbersome investment processes. With the digitization of private offerings, some of these drawbacks and inefficiencies are reduced, facilitating more investors to gain exposure to new investment opportunities and providing institutions with a wider potential investor base and increased revenue opportunities.

Additionally, tokenization of investments with periodic interest payments eliminates the need for time-consuming third-party checks and servicing, allowing for immediate and accurate income distribution to investors via their digital wallets, all while maintaining a transparent blockchain record of the transactions.

Another interesting application are smart contracts, which can be thought of as the automated workforce of blockchain technology, executing transactions on the blockchain when specific conditions are met, ultimately resulting in cost savings for both parties involved in the transaction.

Smart contracts also have a use case in the legal field and have the potential to become legally binding agreements, leading to cost savings by automation of many aspects of contract creation and management. Smart contract transparency, automation, and reduced need for legal (human) intervention can streamline the contract process, minimize disputes, and ultimately lower legal costs while providing a secure and efficient means of executing agreements.

Along with the many benefits that tokenization provides, there are various risks and challenges to this technology too. These challenges include technological issues like scalability, interoperability, and cyber risks, as well as concerns related to governance, AML/CFT compliance, digital identity, data protection, and the legal status of smart contracts.

The tokenization of assets, while offering numerous advantages, can also introduce specific Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (CFT) compliance risks, primarily stemming from the anonymous and borderless nature of blockchain transactions. Here's an elaboration on these risks:

Blockchain transactions are typically pseudonymous, meaning that transactions are associated with public addresses rather than personal identities. Although this can enhance privacy and security, it also makes it virtually impossible to identify the real-world individuals or entities involved in a transaction. AML regulations require businesses to verify the identity of their customers and report suspicious activities. Tokenized assets may complicate the process of identifying the parties in a transaction, potentially enabling money launderers to use the technology for illicit purposes. To address these AML and CFT compliance risks associated with tokenization, regulatory authorities in various countries are working to adapt existing laws to accommodate blockchain technology. This includes implementing regulations to ensure the proper identification of users, transaction monitoring, and the reporting of suspicious activities specifically in the crypto space.

Brief view on the adoption of tokenization outside of the CBDC dimension

Stablecoins, a type of cryptocurrency pegged to real-world currency designed to be fungible, or replicable, are one example of a particularly common tokenized asset. Another example of a tokenized asset is an NFT, a non-fungible token, or a token that can’t be replicated - which is a digital proof of ownership that people can trade. The height of the NFT popularity boom was reached in 2021 and since then the massive decline in value across the entire NFT and crypto market has led to lots of controversy in the NFT space and caused investors to become a lot more skeptical about these particularly volatile tokenized assets.

The current state of CBDCs around the world, and how they work

CBDC’s have surged in popularity in recent years, with various countries exploring the digital version of a centralized, fiat currency. According to a 2021 study, the Bank of International Settlements reported that 86% of central banks were researching CBDCs, 60% experimenting with them, and 14% were conducting pilot projects. As aforementioned, there are many benefits to having e-currencies – they change the money supply and demand structure by speeding up circulation, allowing for faster transmission of monetary policies, an issue that crippled some economies in the past year, in the context of hyperinflation. Furthermore, CBDCs can both expand and enhance digital financial systems in every country, regardless of their current development stage and pre-existing infrastructure. Since all Central Banks are different, and the problems their respective economies face are just as diverse, projects across the world addressed different aspects. For example, Emerging Markets mostly focus on Retail Currencies to reduce cash usage and promote digital finance systems, while Developed Economies are rather interested in improving the safety, efficiency, and resilience of systems that are already in place.

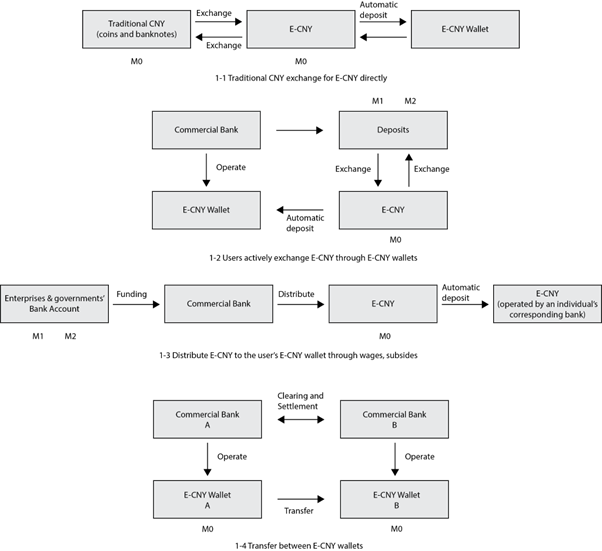

To better understand how CBDCs are used we’ll take a more in-depth look at the developments made across the world. The leader in this move towards digitization is China, which actively researched and developed the technology since 2014. The main projects and by-products are DC/EP (Digital Currency/Electronic Payment) and the e-CNY. The projects are carried out in pilot cities and according to most recent statistics, by the end of 2021 260 million e-CNY personal wallets were opened, with cumulative transactions amounting to 87.5 billion yuan. The renminbi CBDC is designed on a two-tier architecture where the PBoC is responsible for issuance and disposal, connecting between institutions and managing the digital wallet ecosystem. Furthermore, the CB also selects commercial banks that are certified operators of the digital currency, so that they meet different technology and capital requirements. The e-CNY will allow citizens from remote, underdeveloped areas to apply for a wallet without a bank account. The currency also enables offline payments and thus improves accessibility for people living in areas with poor coverage.

The dynamics of e-CNY in current money market circuits

In addition to these positive effects that are already embedded in the e-CNY’s design, further developments of the currency could provide new policy tools and loosen current constraints that PBoC currently faces. For example, in times of recession, the bank could opt for the Helicopter Money policy, as an alternative for Quantitative Easing. e-CNY allows for a smoother distribution of capital through digital accounts and thus increases the feasibility of this unconventional monetary policy. Moreover, the zero lower bound could be loosened by the use of e-CNY, by levying digital wallet storage fees and interest rates.

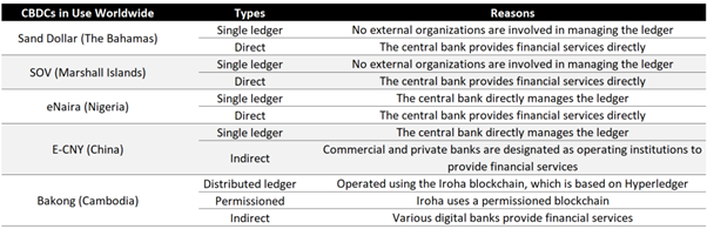

The US is markedly behind on the progress with CBDCs, as they are only researching the transition to digital currencies, with no large-scale projects underway. As for the ECB, some advancements have been made, and the preparation phase for the Digital Euro will commence as of November 2023. This stage implies defining the rulebook for the currency and selecting the providers that will build the infrastructure and provide the digital platform for the Digital Euro. Some other countries that are in the process of adopting CBDC are Sweden with the e-Krona, with the end goal of decreasing dependence on electronic financial systems like Visa or Mastercard. This issue is especially important as the country is amongst the least reliant on cash, with cash in circulation totaling less than 1% of the GDP (as of 2021). In a similar situation are countries like Norway, Finland, the UK, and Singapore to name a few. While these countries have a very well-developed infrastructure of digital financial systems, there are even more that suffer from the lack thereof. Some relevant examples are Uruguay with its e-Peso pilot project, the Bahamas with the Sand Dollar, and Cambodia with the Bakong.

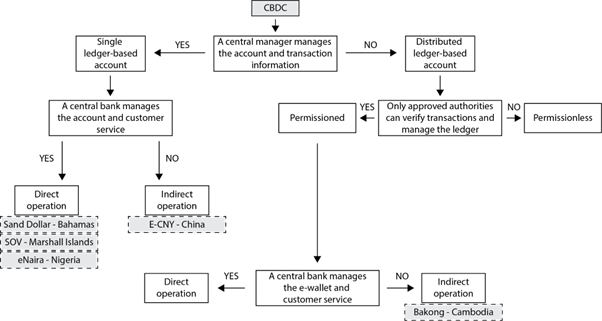

The main difference between these currencies is the number of entities that manage the ledgers. Thus, CBDCs can be classified as single-ledger-based or distributed-ledger-based. In the single-ledger-based system, there is a sole central authority that manages the ledger (such as the Central Bank), and they can act under a uniform, self-imposed standard. As for the distributed-ledger-based system, transactions are shared and synchronized through a ledger that is accessible to multiple entities. Other classifications can be made by accessibility (permissioned systems/permissionless systems), or by distribution channels (direct/indirect).

The US is markedly behind on the progress with CBDCs, as they are only researching the transition to digital currencies, with no large-scale projects underway. As for the ECB, some advancements have been made, and the preparation phase for the Digital Euro will commence as of November 2023. This stage implies defining the rulebook for the currency and selecting the providers that will build the infrastructure and provide the digital platform for the Digital Euro. Some other countries that are in the process of adopting CBDC are Sweden with the e-Krona, with the end goal of decreasing dependence on electronic financial systems like Visa or Mastercard. This issue is especially important as the country is amongst the least reliant on cash, with cash in circulation totaling less than 1% of the GDP (as of 2021). In a similar situation are countries like Norway, Finland, the UK, and Singapore to name a few. While these countries have a very well-developed infrastructure of digital financial systems, there are even more that suffer from the lack thereof. Some relevant examples are Uruguay with its e-Peso pilot project, the Bahamas with the Sand Dollar, and Cambodia with the Bakong.

The main difference between these currencies is the number of entities that manage the ledgers. Thus, CBDCs can be classified as single-ledger-based or distributed-ledger-based. In the single-ledger-based system, there is a sole central authority that manages the ledger (such as the Central Bank), and they can act under a uniform, self-imposed standard. As for the distributed-ledger-based system, transactions are shared and synchronized through a ledger that is accessible to multiple entities. Other classifications can be made by accessibility (permissioned systems/permissionless systems), or by distribution channels (direct/indirect).

Graphical representation of different types of CBDC circuits

Summary view of current CBDCs in use and their structure

Australia’s steps towards tokenization: evidence from the RBA’s recent report

In this context, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) worked with the Digital Finance Cooperative Research Center on a research project examining uses cases and business models that could be enhanced by the introduction of a CBDC in Australia. The report was published on August 23. A limited scale ‘pilot’ digital currency was issued by the central bank in a protected environment where selected industry participants could demonstrate how this innovation may provide value-added to their businesses. The experiment raised awareness about a series of issues associated with the possible future issuance of an Australian CBDC, in terms of legal, regulatory, technical and operational considerations.

With the results of the pilot well in mind, on October 16, Brad Jones, Assistant Governor of the RBA, shared the central bank’s research on the impact of tokenization on Australia’s capital markets. Four options for settlement were discussed: stablecoins, tokenized deposits, cryptocurrencies and wholesale CBDC. Among these, cryptocurrencies were automatically excluded, unsurprisingly for a central bank officer; while stablecoins, which use government bonds as reserve assets, were considered too unpredictable with respect to their possible effects on the bonds market. Tokenized deposits were delineated as the preferred option. These deposits operate within the common two-tiered monetary system, where the central bank, at the top, issues and regulates the official currency - in this case the CBDC and commercial banks offer financial services to the public. Alternatively, the implementation of wholesale CBDC, enhanced by the use of DLT (distributed ledger technology), was considered as a viable possibility. Wholesale CBDC refers to the settlement of interbank transfers, and in general all forms of wholesale transactions, in digital central bank reserves. The aim of this project would be to increase the safety and efficiency of the wholesale market, rather than creating a form of central bank money that may be used by everyone as in retail CBDC.

Delineating the potential benefits of a tokenized exchange presents many difficulties, first of all the fact that it is a greenfield area, which may support the growth of new markets inside the financial world. Despite that, the RBA determined some hypothetical scenarios for cost savings in the currently established markets, in order to have a clearer idea of the potential benefits linked to the introduction of a CBDC.

First, transaction cost savings in Australian financial markets may range between $1 billion and $4 billion per year, reflecting tighter bid-ask spread due to increased trading volumes and gains from atomic settlement driving down other fees, such as savings from reduced collateral requirements, lower incidents of settlement fails and a decrease of cross-border payments fees. Secondly, issuers in the Australian capital markets may save up to $13 billion per year thanks to two factors: a reduction in liquidity premia and a drop in cost of capital by 5 to 24 basis points, which in turn decreases the costs of new issuances. Finally, even if the “tokenized ecosystem” is not yet developed, it is reasonable to assume that both greenfield markets and established markets will benefit from a possible CBDC issuance. New markets may take advantage of programmability and improved informational transparency, while existing ones could increase efficiency by replacing manual processes in the trade lifecycle and introducing fully digital systems.

But what is the RBA’s opinion about tokenization and its possible future introduction in the Australian economy? The central bank is open to the idea of incorporating tokenization into its program on the future of money, recognizing benefits such as increased liquidity, transparency, auditability and reduced intermediary and compliance costs in financial markets. The Bank and the Treasury are currently going on with research on the field and will outline a CBDC roadmap in mid-2024. Anyway, as of today it is clear that RBA’s intention is to use CBDC to enhance the financial system, complementing - rather than substituting – other forms of privately issued digital money as tokenized bank deposits. However, risks such as regulatory uncertainty, compliance obligations, interoperability and fragmentations should not be ignored. The RBA emphasizes the need to conduct further research in order to be able to assess the real entity of these risks and eventually understand how to mitigate them.

Therefore, while the central bank’s focus is on yielding the benefits of tokenization, additional time and effort must be spent on the management of the risks connected to its introduction, by developing a modern regulatory framework that supports both innovation in digital financial services and stability of the financial system as a whole.

The additional hurdles of the Australian case: why implementation is still far out

Tokenizations generally require a long and detailed planning, and the Australian Central Bank has been evaluating this operation for a few years. As a matter of fact, the Australian Financial Review, in an article dated back to 2021, mentioned the RBA’s plan to tokenize assets, and the operation expected an increase in volume from nearly zero at that time, to the goal of $AU32 trillion ($US24 trn) by 2027.

As stated in the article, the RBA aimed at reducing settlement risk and allowing for “atomic settlement”. This term refers to digital cash and asset tokens being exchanged at once and immediately. What is more, one token is transferred if and only if the other is, as well.

Indeed, the introduction of a tokenization in the Australian economy would certainly foster multiple consequences. Benefits outlined by the RBA are many, but so are the risks. Some experts raised concerns regarding the currently poor regulations under which the financial institutions would have to act. However, the uncertainties and problems posed by these inadequate regulatory frameworks might be overcome thanks to the strength and reliability of the Australian economy.

Beyond facilitating electronic transactions, the implementation of Australian CBDCs would allow for clients to have more secure funds. Since customers would not store all their savings into a commercial bank, that could collapse, their funds are safer. Nevertheless, Australian commercial banks have shown to be strong and consistent, even in difficult times, like the 2007 financial crisis, or the recent crises due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

If we take a deeper look into the cons of this tokenization, we see that it would significantly reduce activities and business carried out by commercial banks. Another risk, beyond those already mentioned, is the possibility that commercial banks, against the competitive advantages of digital assets, would not be able to create credit anymore, thus the whole country could experience a slowdown in economic growth. This is broadly due to the fact that holding digital assets is safer than commercial bank deposits, with the aid of government insurance, especially during a banking crisis. Although they could benefit from increased liquidity and efficiency, not only would this be bad for the banks in question, but it would also impact the stock market. One consequence would be that the value of bank stocks drops.

On top of this, with the full control of the central bank over the country’s CBDCs, the RBA could put restrictions on the types of transactions it allows. Furthermore, customers’ and users’ privacy would be more at risk, since the RBA would have all data on transactions within national and international jurisdictions, and also data on single CBDCs’ users.

The asset tokenization is bound to have effects on financial intermediaries, as well, and especially in markets where intermediaries contribute significantly to traded volumes. Generally, transactions in the securitization market can involve up to 12 intermediaries, and a possibly new reduced need for intermediary activities could lead to less competitive prices for market makers. The RBA itself recognizes the difficulty in quantifying the effects on financial institutions.

At the moment, in Australia, any platform that wants to conduct financial services business must hold an AFSL (Australian Financial Services License) - some exceptions apply - and comply with its conditions. In October 2023, the Treasury of the Australian Government published a proposal paper concerning the regulation of tokenized digital assets, proposing to incorporate both “digital asset platforms and other intermediaries within the existing financial services framework”. The paper also provides details about new updated “licensing” methods for financial intermediaries. Nevertheless, the frameworks for this type of regulations are not definite and are still inconclusive.

Conclusions:

Tokenization has emerged as a highly interesting technology in the last decade. Its potential applications to national economic and monetary systems have since been on the radar of central banks worldwide. Efforts to develop CBDCs, or at the very least explore the idea thereof, are underway all around the globe, with a number of countries having already implemented pilot projects and first public initiatives. In this context, Australia is one of the latest advanced economies to announce it is working on assessing the implementation of tokenization in its national payment system, and results of initial research studies have been published. The potential benefits outlined are remarkable, but the country’s Reserve Bank has admitted that there are still significant risks that it has not yet been able to fully address, and that it will undertake further initiatives to do so in the coming periods. In conclusion, central banks are investing heavily into understanding how they can safely implement tokenization in their currency system. Nevertheless, while we seem to be getting closer to this new reality every day, it will realistically take at least another few years before we see any probability of a fully-fledged CBDC being adopted in Australia, or in other advanced economies.

By: Matilde Chiavenato, Chiara Evangelisti, Alexander Lockhart, Matei Sandru

SOURCES

- Reserve Bank of Australia

- Australian Financial Review

- Australian Department of the Treasury

- US Federal Reseve

- European Central Bank

- Bank of Thailand

- Bank for International Settlements

- Investopedia

- Yang, J, Zhou, G (2022) “A study on the influence mechanism of CBDC on monetary policy: An analysis based on e-CNY”

- Chu Y, Lee J, Kim S, Kim H, Yoon Y, Chung H (2022) “Review of Offline Payment Function of CBDC Considering Security Requirements” Applied Sciences