Since its outbreak in the first month of 2020, Covid-19 has changed everyone's life influencing not only people's lifestyle, but also their mindset. Nowadays, when people approach the (probably way too common) topic represented by the pandemic's repercussions, they tend to relate to the context in which they are living: a modernized world, sustained by a strong economic environment such as Western Europe. There are numerous other regions where the consequences of this catastrophe have been way more drastic: a good example could be represented by Indonesia.

With the second-most populous urban area in the world, Jakarta, as capital, the presidential and constitutional republic of Indonesia is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian and Pacific oceans, with the particularity of being composed of 17,504 islands under its territory. Despite usually being overshadowed by other countries in the APAC area, such as Hong-Kong, Singapore & Malaysia; based on IMF estimates the Indonesian archipelago is the 16th largest country by nominal GDP, with those just-cited "competitors", ranked 34th, 37th & 38threspectively.

We could say that Indonesia has a mixed economy: on one hand, government budget spending and its ownership of state-owned enterprises (141) play a vital role in the economic landscape. On the other hand, the private sector if fully operating, sustained by an efficient stock exchange, the so-called Indonesia Stock Exchange, generated by the merger of Jakarta Stock Exchange (JSX) and the Surabaya Stock Exchange (SSX) in 2007, with a current market capitalization of approximately $380.64 bn and 656 listings as of December 2019. Overall, the economy has been growing at a steady rate in the last decades (approximately 5% in terms of annual GDP change) and rating agencies were raising the country's investment-grade every year, reaching an astonishing BBB (stable), by S&P, in May 2019. However, on March 3rd, the President of the Republic of Indonesia announced the first case of COVID-19: in a few months, the country fell into a recession for the first time in 22 years. In case it wasn't clear, even if the overall economy went through a modernization process with a correlated astonishing growing trend, we are still always referring to an archipelago, where a big part of the population is represented by local communities, for whom the main source of income is tourism. Most of those small islands also have a comparative lack of skilled human resources in the medical sector, which leads to poor readiness to countermeasure those kinds of situations. Health facilities are often inadequate and, in many cases, not available: that's why the government has shifted its budget dramatically, to increase spending on healthcare and welfare programs to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. However, what made this situation even worse, is the lack of integrative island-entry monitoring systems, especially in the eastern part of the country, which makes the main maneuver implemented by the government highly ineffective. Travel restrictions impacted highly foreign visitors, the main sources of income, and not particularly Indonesians. Unluckily, as we all know, traveling is one of the main mechanisms for pathogens' spread.

The combination of an overall underdeveloped system, scarce human resources, and a weak health system leads to many islands being easily accessible by people with pandemic pathogens, including Covid-19, without proper recognition.

Based on the information just presented, the overall situation in Indonesia could have been managed better. A good solution, even if very difficult to implement and control, would have been a strict Island lockdown to protect fragile communities. In the situation where drugs and vaccines against coronavirus are not available, stopping traveling seems necessary. On the other hand, there is an important trade-off to keep into consideration. Pursuing this strategy, the pandemic spread risk will reduce and local island inhabitants will be protected from infections. However, there is the potential problem of disturbance in logistics (including food, drugs and health equipment) between regions. In such situations, transportation to support coping strategies should allow and accommodate standard operational procedures to minimize potential pathogens spread.

For what concerns the post-pandemic, significant action needs to be well planned, and control of visitors will still be required. The crucial issue in small islands is represented by the potential mass-tourism in limited space and resources. Promoting a "niche" tourism will allow more rational and strategic options that will allow avoiding some of the main problems, by preserving the important revenues-stream.

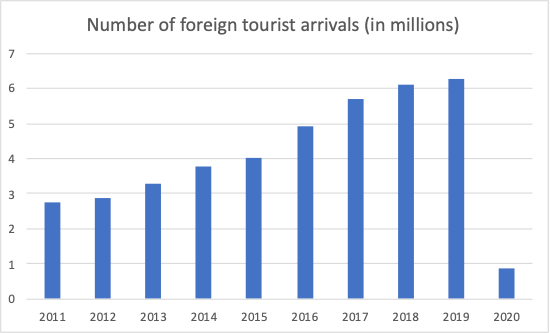

Passing now from a general landscape to the analysis of a specific and interesting case: when we think about Indonesia, probably the picture that populates our mind is a representation of beautiful islands where locals welcome us to spectacular and unspoiled landscapes. Probably, all this can be summarized by the well-known Bali, a small island with a population of 4,2 million and 6,3 million international visitors recorded in 2019. With roughly 80% of the economy depending on tourism based on experts estimate, this natural paradise on earth has probably been through hell for most of 2020 and probably will continue to be. Indonesian President Joko Widodo said in a recent interview that the biggest economic contraction of the overall country was recorded in this region, which is a negative growth of 10.98 percent, driven by the closure of more than 96% of resorts. A simple question arises: how has the pandemic exactly been faced by this small island?

With the second-most populous urban area in the world, Jakarta, as capital, the presidential and constitutional republic of Indonesia is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania, between the Indian and Pacific oceans, with the particularity of being composed of 17,504 islands under its territory. Despite usually being overshadowed by other countries in the APAC area, such as Hong-Kong, Singapore & Malaysia; based on IMF estimates the Indonesian archipelago is the 16th largest country by nominal GDP, with those just-cited "competitors", ranked 34th, 37th & 38threspectively.

We could say that Indonesia has a mixed economy: on one hand, government budget spending and its ownership of state-owned enterprises (141) play a vital role in the economic landscape. On the other hand, the private sector if fully operating, sustained by an efficient stock exchange, the so-called Indonesia Stock Exchange, generated by the merger of Jakarta Stock Exchange (JSX) and the Surabaya Stock Exchange (SSX) in 2007, with a current market capitalization of approximately $380.64 bn and 656 listings as of December 2019. Overall, the economy has been growing at a steady rate in the last decades (approximately 5% in terms of annual GDP change) and rating agencies were raising the country's investment-grade every year, reaching an astonishing BBB (stable), by S&P, in May 2019. However, on March 3rd, the President of the Republic of Indonesia announced the first case of COVID-19: in a few months, the country fell into a recession for the first time in 22 years. In case it wasn't clear, even if the overall economy went through a modernization process with a correlated astonishing growing trend, we are still always referring to an archipelago, where a big part of the population is represented by local communities, for whom the main source of income is tourism. Most of those small islands also have a comparative lack of skilled human resources in the medical sector, which leads to poor readiness to countermeasure those kinds of situations. Health facilities are often inadequate and, in many cases, not available: that's why the government has shifted its budget dramatically, to increase spending on healthcare and welfare programs to respond to the coronavirus outbreak. However, what made this situation even worse, is the lack of integrative island-entry monitoring systems, especially in the eastern part of the country, which makes the main maneuver implemented by the government highly ineffective. Travel restrictions impacted highly foreign visitors, the main sources of income, and not particularly Indonesians. Unluckily, as we all know, traveling is one of the main mechanisms for pathogens' spread.

The combination of an overall underdeveloped system, scarce human resources, and a weak health system leads to many islands being easily accessible by people with pandemic pathogens, including Covid-19, without proper recognition.

Based on the information just presented, the overall situation in Indonesia could have been managed better. A good solution, even if very difficult to implement and control, would have been a strict Island lockdown to protect fragile communities. In the situation where drugs and vaccines against coronavirus are not available, stopping traveling seems necessary. On the other hand, there is an important trade-off to keep into consideration. Pursuing this strategy, the pandemic spread risk will reduce and local island inhabitants will be protected from infections. However, there is the potential problem of disturbance in logistics (including food, drugs and health equipment) between regions. In such situations, transportation to support coping strategies should allow and accommodate standard operational procedures to minimize potential pathogens spread.

For what concerns the post-pandemic, significant action needs to be well planned, and control of visitors will still be required. The crucial issue in small islands is represented by the potential mass-tourism in limited space and resources. Promoting a "niche" tourism will allow more rational and strategic options that will allow avoiding some of the main problems, by preserving the important revenues-stream.

Passing now from a general landscape to the analysis of a specific and interesting case: when we think about Indonesia, probably the picture that populates our mind is a representation of beautiful islands where locals welcome us to spectacular and unspoiled landscapes. Probably, all this can be summarized by the well-known Bali, a small island with a population of 4,2 million and 6,3 million international visitors recorded in 2019. With roughly 80% of the economy depending on tourism based on experts estimate, this natural paradise on earth has probably been through hell for most of 2020 and probably will continue to be. Indonesian President Joko Widodo said in a recent interview that the biggest economic contraction of the overall country was recorded in this region, which is a negative growth of 10.98 percent, driven by the closure of more than 96% of resorts. A simple question arises: how has the pandemic exactly been faced by this small island?

In a desperate attempt to boost this economy, Mr. Widodo decided to reopen the island to domestic tourists in late July. However, the island paid a high price as cases of Covid-19 spiked after an estimated 2,500 holiday-goers came flooding in daily. By the beginning of September, Bali had officially recorded a total of 199 fatalities, making authorities enforcing tighter screening measures and more testing. Among those new measures was a requirement to show a negative test upon arrival. Furthermore, Bali was initially set to open its borders to international tourists by September 11, but with its failed domestic experiment, the island now remains closed indefinitely. As of today, it is pretty sure that no international tourist will probably be lying in Bali's paradisiac white beaches before 2021. Based on the government's warnings, the estimated loss in terms of revenues for this region is more than US$ 10 bn, way bigger than the stimulus package delivered. Regarding the future, Indonesians hope that 2021 will bring renewed hope, but even if there is a resurgence of tourism, a holiday in Bali will likely look very different from what it once was, until a vaccine becomes readily available worldwide.

Quickly concluding, being so famous, Bali represents just a symbolic example of what is going on right now not only in Indonesia, but worldwide, since there is a relevant number of regions tackling the same problems, but to whom people are giving way less attention.

Luca Rivoira