On 19th March 2021, the Federal Reserve announced the suspension by the end of the month of the relief from the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) introduced last year to support banks in the challenging times immediately following the pandemic outbreak. Notwithstanding the crucial role that capital requirements play – especially in crisis time – to preserve the soundness and proper functioning of the financial system, this decision has been welcomed with concerns by the Industry, mostly for its possible implications at micro and macro levels.

Definition of capital requirements and their role

Capital requirements regulate the amount of liquid capital that depository or financial institutions must hold, with respect to their level of assets. They are different from reserve requirements, which focus on the portion of assets that a bank must retain in cash or highly liquid assets. Capital ratios are used to evaluate banks’ strength and safety, as they represent the percentage of banks’ capital to their risk-weighted assets. They are supported by leverage ratio requirements, defined as supplementary leverage ratio (SLR).

Their main purpose is to limit the exposure of financial institutions to the risk of taking on excessive leverage, thus increasing the probabilities of becoming insolvent and defaulting. As a consequence, they ensure the availability of enough capital to guarantee the honouring of withdrawals, even in the case of operating losses. Even though capital requirements assure the safety of the financial system, they are highly criticised as they restrain banks’ risk-taking strategies and reduce competition in the industry, since they strongly affect smaller institutions. In addition, the costs of maintaining a certain level of capital increase the cost of borrowing.

Standard levels are set by agencies such as the Federal Reserve Board (the FED), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Since capital requirements’ implementation, the majority of capital reforms have been a direct consequence of economic or financial crises.

Historical development

The introduction of capital requirements was triggered by Mexico, and in general Latin America, in 1982, when the country was unable to pay interests on its national debt. The episode paved the way for a wave of legislations, such as the International Lending Supervision Act of 1983.

In particular, capital requirements rules are centered on the Basel Accords, established by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. The first Basel agreement, named Basel I, was published in 1988 and introduced risk-weighted assets (RWA). It was then substituted by Basel II in 2004, which required a minimum capital ratio of 8%. In Basel II, bank capital has been halved in Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital, the former consisting of equity and disclosed reserves, while the latter of undisclosed reserves, revaluation reserves, general provisions, hybrid instruments, and subordinated-term debt. Finally, as a consequence of the Great Financial Crisis, Basel III was introduced in 2010, shortly after the signing of the Dodd-Frank Act (DFA), which aims at ensuring that banks have enough capital to resist shocks to the banking system.

According to the aforementioned regulations, an adequately capitalized bank should be characterized by a Tier 1 capital ratio of at least 4%, a combined Tier 1 and Tier 2 ratio of 8%, and a leverage ratio of 4%. However, considering the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB), which is a mandatory capital that banks must hold in addition to the minimum requirements, the total capital ratio reaches a level of at least 10.5%.

Buffers were introduced under Basel III and their purpose is to ensure a more resilient global banking system, especially regarding issues of liquidity. The CCyB is calculated as the weighted average of the buffers to which each bank has credit exposure and is part of a set of macroprudential instruments, designed to help counter pro-cyclicality in the financial system.

The suspension of the capital relief: the main consequences on US Banks’ operations and Capital Markets

When looking at the importance of capital requirements in today’s banking world, it is relevant to consider the latest decisions of the Federal Reserve in trying to ensure stability in the banking sector through changes and updates on the rules to which financial institutions are subject. In this regard, on 19th March 2021, the Federal Reserve announced the suspension at the end of the month of the capital relief that was introduced at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to guarantee continuous lending to households and businesses and to have a better stabilisation in the bond market. In fact, both dynamics were endangered by the uncertainty and volatility caused by the pandemic.

In particular, the Fed opted for a temporary change in the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), which requires banks to hold capital equal to at least 3% of their assets and 5% for the largest and most significant ones. The main concession to financial institutions consisted in the possibility to exclude cash reserves held at the central bank and holdings of US Treasuries from the assets included in the calculation of the above-mentioned ratio.

The discussion about the potential extension of the relief has been a main subject in the financial world in the past few weeks, extending also to a more political exchange of views. In fact, on one side, Democrats like Elizabeth Warren, the US senator from Massachusetts and former Democratic presidential candidate, insisted about the potential weakening of the regulatory framework introduced after the financial crisis implied by its possible extension and, on the other side, Republicans, industry executives and banks hoped for the continuing application of the relief as they were worried about the possible negative consequences of balance sheet constraints on banks’ operations in such difficult times.

It has to be noticed that, in the past few months, the capital relief was actually able to achieve its initial objective of stabilisation of the market and a recent analysis of the FT showed that actually the largest US banks are characterized by cushions that are even larger than the 5% threshold implied by the SLR, even when considering the removal of the relief and the implied consideration of cash reserves in the central banks and US Treasuries.

Despite the previous point, the reaction of the US Banks stocks to the news has not been positive at all, considering the hope for the extension of the application of the measure and the possible threats that the update of the Fed can have on the banks’ operations in the medium term. In particular, as it can be seen here below, stocks of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo (Figure 1 and 2) were characterized by a substantial drop after the announcement, confirming even more how the regulatory framework plays a fundamental role in determining the ability of banks to boost profits and conduct their role of providing funds to the real economy. This is mainly due to the fact that, even if large banks show a relevant ability to stay over the required level of 5% of capital over their assets, it has to be noticed that the actual percentage shows a relevant decrease of the ratio as a natural consequence of the measure and it poses further constraints to be respected. In this sense, it has also to be underlined that some bank executives have warned that one of the consequences of the new landscape could be the possibility to turn deposits away.

Definition of capital requirements and their role

Capital requirements regulate the amount of liquid capital that depository or financial institutions must hold, with respect to their level of assets. They are different from reserve requirements, which focus on the portion of assets that a bank must retain in cash or highly liquid assets. Capital ratios are used to evaluate banks’ strength and safety, as they represent the percentage of banks’ capital to their risk-weighted assets. They are supported by leverage ratio requirements, defined as supplementary leverage ratio (SLR).

Their main purpose is to limit the exposure of financial institutions to the risk of taking on excessive leverage, thus increasing the probabilities of becoming insolvent and defaulting. As a consequence, they ensure the availability of enough capital to guarantee the honouring of withdrawals, even in the case of operating losses. Even though capital requirements assure the safety of the financial system, they are highly criticised as they restrain banks’ risk-taking strategies and reduce competition in the industry, since they strongly affect smaller institutions. In addition, the costs of maintaining a certain level of capital increase the cost of borrowing.

Standard levels are set by agencies such as the Federal Reserve Board (the FED), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the Bank for International Settlements (BIS). Since capital requirements’ implementation, the majority of capital reforms have been a direct consequence of economic or financial crises.

Historical development

The introduction of capital requirements was triggered by Mexico, and in general Latin America, in 1982, when the country was unable to pay interests on its national debt. The episode paved the way for a wave of legislations, such as the International Lending Supervision Act of 1983.

In particular, capital requirements rules are centered on the Basel Accords, established by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision. The first Basel agreement, named Basel I, was published in 1988 and introduced risk-weighted assets (RWA). It was then substituted by Basel II in 2004, which required a minimum capital ratio of 8%. In Basel II, bank capital has been halved in Tier 1 and Tier 2 capital, the former consisting of equity and disclosed reserves, while the latter of undisclosed reserves, revaluation reserves, general provisions, hybrid instruments, and subordinated-term debt. Finally, as a consequence of the Great Financial Crisis, Basel III was introduced in 2010, shortly after the signing of the Dodd-Frank Act (DFA), which aims at ensuring that banks have enough capital to resist shocks to the banking system.

According to the aforementioned regulations, an adequately capitalized bank should be characterized by a Tier 1 capital ratio of at least 4%, a combined Tier 1 and Tier 2 ratio of 8%, and a leverage ratio of 4%. However, considering the countercyclical capital buffer (CCyB), which is a mandatory capital that banks must hold in addition to the minimum requirements, the total capital ratio reaches a level of at least 10.5%.

Buffers were introduced under Basel III and their purpose is to ensure a more resilient global banking system, especially regarding issues of liquidity. The CCyB is calculated as the weighted average of the buffers to which each bank has credit exposure and is part of a set of macroprudential instruments, designed to help counter pro-cyclicality in the financial system.

The suspension of the capital relief: the main consequences on US Banks’ operations and Capital Markets

When looking at the importance of capital requirements in today’s banking world, it is relevant to consider the latest decisions of the Federal Reserve in trying to ensure stability in the banking sector through changes and updates on the rules to which financial institutions are subject. In this regard, on 19th March 2021, the Federal Reserve announced the suspension at the end of the month of the capital relief that was introduced at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic in order to guarantee continuous lending to households and businesses and to have a better stabilisation in the bond market. In fact, both dynamics were endangered by the uncertainty and volatility caused by the pandemic.

In particular, the Fed opted for a temporary change in the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), which requires banks to hold capital equal to at least 3% of their assets and 5% for the largest and most significant ones. The main concession to financial institutions consisted in the possibility to exclude cash reserves held at the central bank and holdings of US Treasuries from the assets included in the calculation of the above-mentioned ratio.

The discussion about the potential extension of the relief has been a main subject in the financial world in the past few weeks, extending also to a more political exchange of views. In fact, on one side, Democrats like Elizabeth Warren, the US senator from Massachusetts and former Democratic presidential candidate, insisted about the potential weakening of the regulatory framework introduced after the financial crisis implied by its possible extension and, on the other side, Republicans, industry executives and banks hoped for the continuing application of the relief as they were worried about the possible negative consequences of balance sheet constraints on banks’ operations in such difficult times.

It has to be noticed that, in the past few months, the capital relief was actually able to achieve its initial objective of stabilisation of the market and a recent analysis of the FT showed that actually the largest US banks are characterized by cushions that are even larger than the 5% threshold implied by the SLR, even when considering the removal of the relief and the implied consideration of cash reserves in the central banks and US Treasuries.

Despite the previous point, the reaction of the US Banks stocks to the news has not been positive at all, considering the hope for the extension of the application of the measure and the possible threats that the update of the Fed can have on the banks’ operations in the medium term. In particular, as it can be seen here below, stocks of JPMorgan Chase and Wells Fargo (Figure 1 and 2) were characterized by a substantial drop after the announcement, confirming even more how the regulatory framework plays a fundamental role in determining the ability of banks to boost profits and conduct their role of providing funds to the real economy. This is mainly due to the fact that, even if large banks show a relevant ability to stay over the required level of 5% of capital over their assets, it has to be noticed that the actual percentage shows a relevant decrease of the ratio as a natural consequence of the measure and it poses further constraints to be respected. In this sense, it has also to be underlined that some bank executives have warned that one of the consequences of the new landscape could be the possibility to turn deposits away.

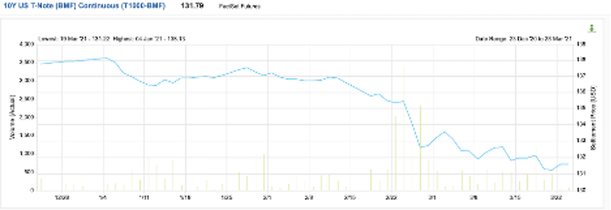

In addition to that, the implications of the announcement of the Federal Reserve led to a sold off of US Treasuries (Figure 3), already under pressure for the tensions on bond markets determined by the strong expectations of increasing inflation in the US and by the continuing dovish policy confirmed by the Fed.

Overall, it can be said that the suspension of the capital relief at the end of March poses an additional challenge on US Banks’ way of doing business and it can be seen as another confirmation of the real hope and belief of relevant authorities that the US Economy can recover quickly thanks to the ongoing vaccination campaign and the extraordinary measures already put in place in terms of fiscal and monetary policy by the US government and the Federal Reserve. Additionally, understanding how the latest decision of the Fed on capital requirements will actually affect banks’ profitability and their stability will be a matter of time, but for sure the recent news was not the one the banking industry was hoping for.

Perspectives about the impacts of the Fed's decision

The above-mentioned decision by Fed not to extend the relief from the Supplementary Leverage Ratio is causing worries among banks and industry representatives especially because the unusual conditions that originally prompted the easing – including the Fed’s massive intervention in the Treasury market - are still in place.

Going back to March 2020 – when the loosening of capital requirements was introduced – is crucial in order to see the rationales behind the relief’s concession and could be useful to give a perspective about the possible impacts of the recent Fed’s decision at micro and macro level.

One of the conditions that during the turmoil of the pandemic pushed the decision by Fed to ease the SLR for large banks was the evidence of a dramatical deterioration in the ease of buying and selling even the safest, most high-quality assets such as the 30-year US government bonds. In mid-March 2020, banks, foreign central banks, and hedge funds, among others, had sought to sell Treasuries and other bonds in a desperate need to raise cash, but the refusal to bid by some US banks was meaningful of the scarce liquidity in the market. In this context, the rule behind the SLR has been blamed for discouraging banks from storing Treasuries on their balance sheets because doing so reduces their supplementary leverage ratio, undermining their ability to act as intermediaries in the Treasury market. The main contradiction behind the capital requirement is indeed that SLR, unlike other bank capital requirements, does not take risk into account, therefore leading Treasuries and cash reserves to be considered as risky as other types of assets.

The easing of the regulation in March 2020 intended to give banks flexibility in which assets they could hold to meet regulatory requirements during the turmoil of the pandemic. The change was effective in making it easier for banks to absorb the extra cash the Fed was pumping into financial markets and in facilitating trading in US Treasuries, also letting banks to take in extra deposits from customers and extend credit to companies facing a cash crunch.

However, in a moment where Fed is keeping flooding the banking system with cash reserves (total bank reserves now stand at nearly $3.5 trillion, up from roughly $1.5 trillion before the pandemic), one possible impact at macro level of restoring this capital requirement could be the unwillingness of large banks to hold treasury securities in their balance sheets, therefore ceasing to acting as an additional player – together with the Central Bank – to bring normalcy back to the Treasury market. In other words, the reimposition of this capital requirement could lead banks to keep fewer reserves in their Balance Sheets with potential dramatic consequences on funding markets. With regards to this, it must be noticed that the immediate consequence of an excess of supply of Treasury bonds would be an increase in the yield of the 10-year Treasury bond - benchmark for mortgage rates – and therefore the increase in borrowing costs. The latter, as well as a general reduction in banks’ ability to extend credit to companies and consumers (the so-called “credit crunch”) are the main possible consequences from a micro perspective of SLR restoration.

Furthermore, similarly to what usually happens after a tightening in capital requirements, the temporary negative loan supply induced by Fed’s decision could negatively affect investments, consumption, housing activity and production, with potential adverse consequences in the post-pandemic US recovery.

BSCM would like to thank FactSet for giving us access to their platform and providing charts and data.

Orazio Gianmarco Olivieri

Chiara Pampillonia

Tommaso Tenti

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

The above-mentioned decision by Fed not to extend the relief from the Supplementary Leverage Ratio is causing worries among banks and industry representatives especially because the unusual conditions that originally prompted the easing – including the Fed’s massive intervention in the Treasury market - are still in place.

Going back to March 2020 – when the loosening of capital requirements was introduced – is crucial in order to see the rationales behind the relief’s concession and could be useful to give a perspective about the possible impacts of the recent Fed’s decision at micro and macro level.

One of the conditions that during the turmoil of the pandemic pushed the decision by Fed to ease the SLR for large banks was the evidence of a dramatical deterioration in the ease of buying and selling even the safest, most high-quality assets such as the 30-year US government bonds. In mid-March 2020, banks, foreign central banks, and hedge funds, among others, had sought to sell Treasuries and other bonds in a desperate need to raise cash, but the refusal to bid by some US banks was meaningful of the scarce liquidity in the market. In this context, the rule behind the SLR has been blamed for discouraging banks from storing Treasuries on their balance sheets because doing so reduces their supplementary leverage ratio, undermining their ability to act as intermediaries in the Treasury market. The main contradiction behind the capital requirement is indeed that SLR, unlike other bank capital requirements, does not take risk into account, therefore leading Treasuries and cash reserves to be considered as risky as other types of assets.

The easing of the regulation in March 2020 intended to give banks flexibility in which assets they could hold to meet regulatory requirements during the turmoil of the pandemic. The change was effective in making it easier for banks to absorb the extra cash the Fed was pumping into financial markets and in facilitating trading in US Treasuries, also letting banks to take in extra deposits from customers and extend credit to companies facing a cash crunch.

However, in a moment where Fed is keeping flooding the banking system with cash reserves (total bank reserves now stand at nearly $3.5 trillion, up from roughly $1.5 trillion before the pandemic), one possible impact at macro level of restoring this capital requirement could be the unwillingness of large banks to hold treasury securities in their balance sheets, therefore ceasing to acting as an additional player – together with the Central Bank – to bring normalcy back to the Treasury market. In other words, the reimposition of this capital requirement could lead banks to keep fewer reserves in their Balance Sheets with potential dramatic consequences on funding markets. With regards to this, it must be noticed that the immediate consequence of an excess of supply of Treasury bonds would be an increase in the yield of the 10-year Treasury bond - benchmark for mortgage rates – and therefore the increase in borrowing costs. The latter, as well as a general reduction in banks’ ability to extend credit to companies and consumers (the so-called “credit crunch”) are the main possible consequences from a micro perspective of SLR restoration.

Furthermore, similarly to what usually happens after a tightening in capital requirements, the temporary negative loan supply induced by Fed’s decision could negatively affect investments, consumption, housing activity and production, with potential adverse consequences in the post-pandemic US recovery.

BSCM would like to thank FactSet for giving us access to their platform and providing charts and data.

Orazio Gianmarco Olivieri

Chiara Pampillonia

Tommaso Tenti

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.