China is struggling to restore confidence in its stock markets, which are being weighed down by a massive amount of shares that have been pledged as collateral as credit-starved companies seek to raise funds.

Tight regulations in China’s credit markets mean that many companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, have limited financing from banks or other sources, and policymakers have yet to promise any actual money, due to these many of those companies have turned to pledging shares to finance companies as a way of raising cash.

“Using pledged shares to borrow has become a very popular, and very important funding tool,” said Wang Jin, a Shanghai-based lawyer who is dealing with an increasing number of disputes involving collateralized loans.

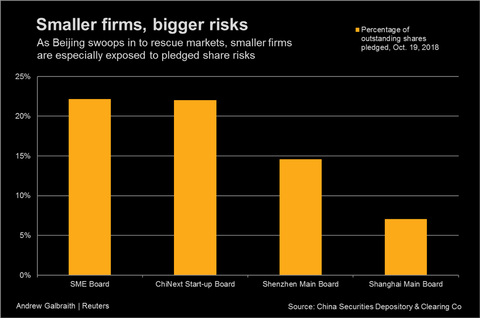

About $620 billion worth of Chinese shares currently trading on Chinese markets have been pledged, mostly by small and medium-sized companies. But now, the nearly 20 percent slump in the broader market this year has triggered margin calls, forced liquidations, ownership changes, business disruptions and bond defaults for hundreds of listed firms.

Shanghai-based economists predict that forced liquidations are likely to have a disastrous effect on companies involved, and the impact to the real economy would be even bigger if the contagion spreads to affiliates and other businesses along the value chain.

Looking back to recent history we can see that, during the market slump of 2015/16, over 1,000 companies suspended share trading to avoid margin call risks. But regulators have now tightened rules for share suspension, giving no buffer to listed firms facing risks of forced liquidations.

This means that the private sector, which drives half the economy and generates the bulk of jobs, is going to face huge funding problems, unless Beijing steps in with state money. Beijing threw money at the problem in 2015, even asking state-owned funds to buy shares. Now, it is asking private sector funds to help these companies. Chinese vice Premier Liu He, central bank governor Yi Gang, as well as China’s securities, and banking and insurance regulators, have called for private funds to pump money into struggling listed companies. In one of Beijing's latest interventions, the Securities Association of China was that 11 securities firms will form a $100 billion yuan ($14.5 billion) asset management plan to take some pressure off "share pledges" for companies with good development prospects.

The Shanghai composite has fallen more than 20 percent this year amid worries about economic slowdown and rising tensions with the United States, China's largest trading partner. It is one of the world's worst performing stock markets in 2018.

Goldman Sachs' China strategist Kinger Lau said in a note on Saturday that based on data at that time, about 1 trillion yuan of stock-pledged loans could face the risk of a margin call to pay up. That figure increases by about 100 billion yuan if the stock market falls 5 percent, the report said. Lau pointed out that governments in Beijing, Shenzhen and Hangzhou announced last week that funds will be established to help local firms with share pledge difficulties."Against the backdrop of high leverage and weak sentiment in both the real economy and financial market, it is critical for the government to restore confidence among the people," J.P. Morgan Asset Management global market strategists, Marcella Chow and Chaoping Zhu, said.

Many analysts predict the government rhetoric to delay rather than diffuse the implosion of the massive “pledged shares” minefield among smaller companies. “Risk (is) under control, with the exception of some small-to-mid caps,” wrote Gao Ting, Head of China Strategy at UBS Securities.

Tight regulations in China’s credit markets mean that many companies, especially small and medium-sized enterprises, have limited financing from banks or other sources, and policymakers have yet to promise any actual money, due to these many of those companies have turned to pledging shares to finance companies as a way of raising cash.

“Using pledged shares to borrow has become a very popular, and very important funding tool,” said Wang Jin, a Shanghai-based lawyer who is dealing with an increasing number of disputes involving collateralized loans.

About $620 billion worth of Chinese shares currently trading on Chinese markets have been pledged, mostly by small and medium-sized companies. But now, the nearly 20 percent slump in the broader market this year has triggered margin calls, forced liquidations, ownership changes, business disruptions and bond defaults for hundreds of listed firms.

Shanghai-based economists predict that forced liquidations are likely to have a disastrous effect on companies involved, and the impact to the real economy would be even bigger if the contagion spreads to affiliates and other businesses along the value chain.

Looking back to recent history we can see that, during the market slump of 2015/16, over 1,000 companies suspended share trading to avoid margin call risks. But regulators have now tightened rules for share suspension, giving no buffer to listed firms facing risks of forced liquidations.

This means that the private sector, which drives half the economy and generates the bulk of jobs, is going to face huge funding problems, unless Beijing steps in with state money. Beijing threw money at the problem in 2015, even asking state-owned funds to buy shares. Now, it is asking private sector funds to help these companies. Chinese vice Premier Liu He, central bank governor Yi Gang, as well as China’s securities, and banking and insurance regulators, have called for private funds to pump money into struggling listed companies. In one of Beijing's latest interventions, the Securities Association of China was that 11 securities firms will form a $100 billion yuan ($14.5 billion) asset management plan to take some pressure off "share pledges" for companies with good development prospects.

The Shanghai composite has fallen more than 20 percent this year amid worries about economic slowdown and rising tensions with the United States, China's largest trading partner. It is one of the world's worst performing stock markets in 2018.

Goldman Sachs' China strategist Kinger Lau said in a note on Saturday that based on data at that time, about 1 trillion yuan of stock-pledged loans could face the risk of a margin call to pay up. That figure increases by about 100 billion yuan if the stock market falls 5 percent, the report said. Lau pointed out that governments in Beijing, Shenzhen and Hangzhou announced last week that funds will be established to help local firms with share pledge difficulties."Against the backdrop of high leverage and weak sentiment in both the real economy and financial market, it is critical for the government to restore confidence among the people," J.P. Morgan Asset Management global market strategists, Marcella Chow and Chaoping Zhu, said.

Many analysts predict the government rhetoric to delay rather than diffuse the implosion of the massive “pledged shares” minefield among smaller companies. “Risk (is) under control, with the exception of some small-to-mid caps,” wrote Gao Ting, Head of China Strategy at UBS Securities.

The drop in share prices “has greatly reduced funding options for many listed firms,” said Di Yang, analyst at credit rating agency China Bond Rating Co Ltd. Tan Jialong, director of private securities investment at conglomerate Zendai Group, suspects that this year’s crisis could deal a bigger blow to the real economy, different from the 2015-16 market crash which hit mainly highly-leveraged stock punters.“The stock market drop this time is affecting operations of many listed companies, at a time when economic prospects are not good,” Tan said. The private sector’s role in mainland China cannot be overstated. The sector contributes 50 percent of tax, over 60 percent of GDP, over 80 percent of urban employment and over 90 percent of newly-created jobs.Tan Jialong said that his group has no plans yet to answer the government’s call to rescue struggling listed firms partly because the worsening economic environment is disrupting existing valuation models, and there is no guarantee that investing now would be eventually profitable.

Vladimer Chogoshvili

Vladimer Chogoshvili