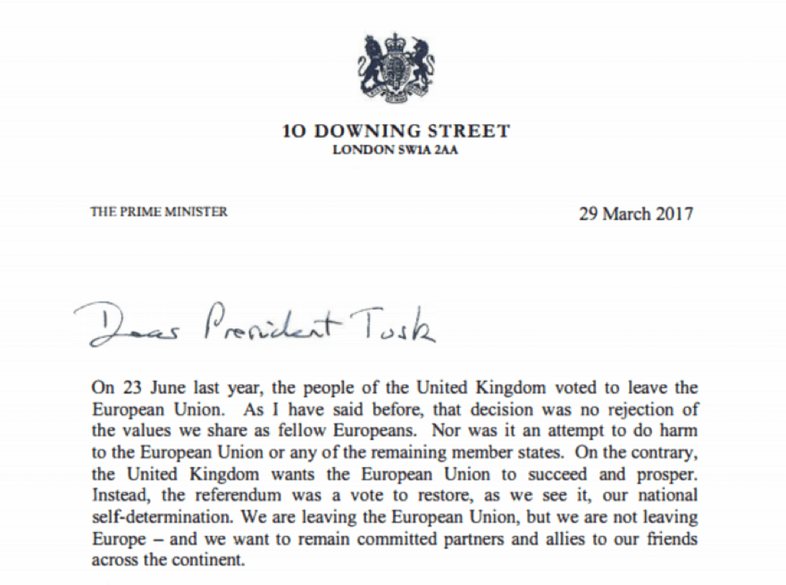

A hard beginning. On March 29 the European Council received the letter from Prime Minister Theresa May which stated the UK’s intention to leave the European Union, officially triggering Article 50. But what exactly does it mean?

Its first effect is to mark the beginning of negotiations between the UK and the member states, mainly concerning access to the free market, free movement of people, citizen’s rights and trade agreements. It is also necessary to discuss the settling of UK’s outstanding commitments to the EU. Given the value of the bill (up to £50 Billions), this issue, by itself, threatens the possibility of a deal. And in case one was not agreed, PM Theresa May has promised to enact a low-tax and low-regulation regime to attract business from the overseas.

But there is also a second, gloomier implication. Article 50 starts a 2 years countdown after which the UK will, by a deal or forcefully, leave the European Union. Though an extension of the terms could be agreed between the UK and member states, the process has been regarded as not reversible. But is it really? Not quite so, as The Economist notes.

By admission of the Brexit secretary David Davis himself, any deal negotiated under Article 50 will require parliamentary approval. Lord Hope, a former Supreme Court justice, has declared that the court’s former ruling, which gave Parliament authority over Article 50, may also require further primary legislation before Brexit actually happens. The government has already planned that a “Great Repeal Bill” will be needed to end the authority of European law in Britain while also ensuring legal continuity. Recently it emerged that at least seven more bills are necessary. Thus, it is evident that Parliament still plays an important role.

Yet the House of Commons, of all places, hardly seems to pose a threat to Brexit, despite its bipartisan support for “remain” before the referendum. This is due not only to May’s Conservatives’ steady majority, but also to Jeremy Corbyn’s strategy of not opposing the 52% of voters who expressed the will to leave the EU. But given insistent calls for a change of Labour’s poor leadership, UK’s second party may eventually emerge from irrelevance and reclaim the role of main opposition to the Conservative government.

Currently, however, the only concrete opposition to Brexit, apart from Scotland and the pound, are the Liberal Democrats, who staged a pro-EU march on the day of the anniversary of the Rome Treaties, and the House of Lords, whose recent amendment to the Brexit bill, concerning the rights of EU citizens residing in the UK, was later vetoed by Commons.

Parliamentary manoeuvres over Brexit may not be finished, but the front has now moved from London to Brussels. With a 2 years deadline and a PM who prefers no deal over a bad deal, negotiations are bound to be harsh. Let’s hope that, as the proverb goes, this hard beginning maketh a good ending.

Pietro Menoni

But there is also a second, gloomier implication. Article 50 starts a 2 years countdown after which the UK will, by a deal or forcefully, leave the European Union. Though an extension of the terms could be agreed between the UK and member states, the process has been regarded as not reversible. But is it really? Not quite so, as The Economist notes.

By admission of the Brexit secretary David Davis himself, any deal negotiated under Article 50 will require parliamentary approval. Lord Hope, a former Supreme Court justice, has declared that the court’s former ruling, which gave Parliament authority over Article 50, may also require further primary legislation before Brexit actually happens. The government has already planned that a “Great Repeal Bill” will be needed to end the authority of European law in Britain while also ensuring legal continuity. Recently it emerged that at least seven more bills are necessary. Thus, it is evident that Parliament still plays an important role.

Yet the House of Commons, of all places, hardly seems to pose a threat to Brexit, despite its bipartisan support for “remain” before the referendum. This is due not only to May’s Conservatives’ steady majority, but also to Jeremy Corbyn’s strategy of not opposing the 52% of voters who expressed the will to leave the EU. But given insistent calls for a change of Labour’s poor leadership, UK’s second party may eventually emerge from irrelevance and reclaim the role of main opposition to the Conservative government.

Currently, however, the only concrete opposition to Brexit, apart from Scotland and the pound, are the Liberal Democrats, who staged a pro-EU march on the day of the anniversary of the Rome Treaties, and the House of Lords, whose recent amendment to the Brexit bill, concerning the rights of EU citizens residing in the UK, was later vetoed by Commons.

Parliamentary manoeuvres over Brexit may not be finished, but the front has now moved from London to Brussels. With a 2 years deadline and a PM who prefers no deal over a bad deal, negotiations are bound to be harsh. Let’s hope that, as the proverb goes, this hard beginning maketh a good ending.

Pietro Menoni