A bit of a turmoil is happening on the island of Borneo. Being the fourth largest oil producer in Asia and the ninth largest exporter of liquefied natural gas worldwide, the sultanate of Brunei, made up of two enclaves on Malaysian Borneo, has one of the most energy price-sensitive economy. With an area of only 5,700 km2 (Italy area is slightly more than 300,000 Km2), such nation strongly relies on imports for agricultural products, motorcars and electrical products. More specifically, it imports 60% of its food requirements and, of that amount, around 75% come from the ASEAN countries. Nonetheless, steadily high oil prices allowed such an economy to be sustainable over time, at least until recent years.

Since July 2014 the oil price sharply dropped to a new equilibrium level, set between 40-60 $/barrel, (from an average 100 $/barrel during 2011-2014), which heavily affected the Sultanate’s economic and political soundness. The International Monetary Fund estimates oil and gas revenues in the sultanate fell by three-quarters in the four years to 2015-16, as a consequence of this price changes.

Such price collapse poses a threat to Brunei for many reasons:

First, it favours China attempts at expanding its control over the oil-rich waters of South China Sea. The sultanate has historically been able to rely on its own wealth and to reject the Chinese attempts but now the scenario has changed. China is currently making new infrastructural investments, with projects including bridges, export factories and a petrochemical plant in addition to the massive project of building an infrastructural connection between China, Russia, Europe and Middle East (the project is also known as the New Silky Road), thus making its presence in the strategic area more relevant.

On the other hand, the long-term high oil price made Brunei’s government more comfortable about its economic capacity and more willing to undertake expansive fiscal policies thus providing subsidies, such as the one for housing and for consumer goods. As the energy price trend turned, this short-sighted strategy revealed its flaws. The younger generation is now struggling with increasing unemployment and future pensions, which are expected to be lower than the current ones.

Both internal issues, linked to too “relaxed” policies, and external ones, caused by the high exposure to imports and the Chinese political threat, make Brunei’s situation very critical.

For such reasons the government is trying to diversify the economy by promoting entrepreneurship and eco-tourism but it is not easy, as workers have been made “less hungry” to work by the “oil money”, which supported the economy over the last period. Moreover, the royal family has recently made headlines as authorities charged the younger brother of the sultan with misappropriation of a large amount of money from the Brunei Investment Agency, thus exacerbating even more the political tensions.

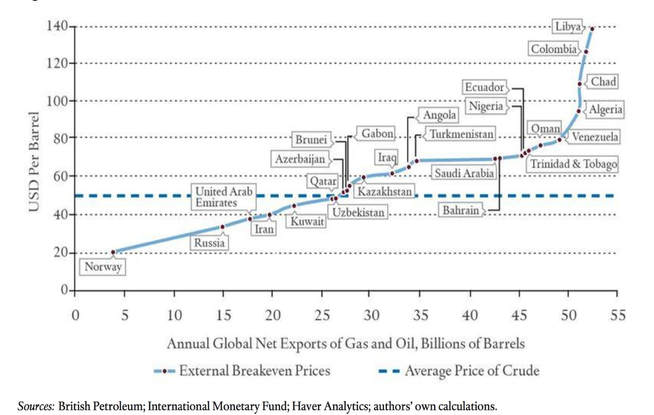

Let’s now focus on the economic impact of the current level of oil price on the Bruneian and other oil-dependent economies. The price of oil and natural gas has roughly halved in the past three years; that’s redistributed about $1 trillion in yearly export earnings from net producers to net consumers. A report from Brad Setser and Cole Frank, two members of the Council on Foreign Relations, shows which are the main countries exposed to such markets movements and at what extent.

The authors analysed what they call the “external breakeven”: the current account deficit minus the oil and gas trade surplus (i.e. oil and gas net exports), divided by net oil and gas exports in barrels of oil equivalent. In other words, they used an index yielding the price required for a country’s current account balance to actually balance.

As Brunei does, also most significant oil and gas exporters have little in the way of domestic industry and many of them are incapable of feeding themselves without imports from the rest of the world (Russia is a notable exception). Some, such as Norway and a few of the smaller Gulf states, amassed enormous foreign reserves to protect themselves from price declines when times were good, but many did not, instead preferring to spend the temporary windfall on everything from military misadventures to experiments in “Bolivarian socialism”. As mentioned above, Brunei belongs to the latter group, with its expansive fiscal policy.

Furthermore, there are big differences between the impact of the oil price on government budgets in places that peg their currencies to the dollar, such as Saudia Arabia and the Gulf emirates, and places with floating currencies, such as Norway and Russia.

The below graph represents the distribution of the countries by breakeven oil price.

Since July 2014 the oil price sharply dropped to a new equilibrium level, set between 40-60 $/barrel, (from an average 100 $/barrel during 2011-2014), which heavily affected the Sultanate’s economic and political soundness. The International Monetary Fund estimates oil and gas revenues in the sultanate fell by three-quarters in the four years to 2015-16, as a consequence of this price changes.

Such price collapse poses a threat to Brunei for many reasons:

First, it favours China attempts at expanding its control over the oil-rich waters of South China Sea. The sultanate has historically been able to rely on its own wealth and to reject the Chinese attempts but now the scenario has changed. China is currently making new infrastructural investments, with projects including bridges, export factories and a petrochemical plant in addition to the massive project of building an infrastructural connection between China, Russia, Europe and Middle East (the project is also known as the New Silky Road), thus making its presence in the strategic area more relevant.

On the other hand, the long-term high oil price made Brunei’s government more comfortable about its economic capacity and more willing to undertake expansive fiscal policies thus providing subsidies, such as the one for housing and for consumer goods. As the energy price trend turned, this short-sighted strategy revealed its flaws. The younger generation is now struggling with increasing unemployment and future pensions, which are expected to be lower than the current ones.

Both internal issues, linked to too “relaxed” policies, and external ones, caused by the high exposure to imports and the Chinese political threat, make Brunei’s situation very critical.

For such reasons the government is trying to diversify the economy by promoting entrepreneurship and eco-tourism but it is not easy, as workers have been made “less hungry” to work by the “oil money”, which supported the economy over the last period. Moreover, the royal family has recently made headlines as authorities charged the younger brother of the sultan with misappropriation of a large amount of money from the Brunei Investment Agency, thus exacerbating even more the political tensions.

Let’s now focus on the economic impact of the current level of oil price on the Bruneian and other oil-dependent economies. The price of oil and natural gas has roughly halved in the past three years; that’s redistributed about $1 trillion in yearly export earnings from net producers to net consumers. A report from Brad Setser and Cole Frank, two members of the Council on Foreign Relations, shows which are the main countries exposed to such markets movements and at what extent.

The authors analysed what they call the “external breakeven”: the current account deficit minus the oil and gas trade surplus (i.e. oil and gas net exports), divided by net oil and gas exports in barrels of oil equivalent. In other words, they used an index yielding the price required for a country’s current account balance to actually balance.

As Brunei does, also most significant oil and gas exporters have little in the way of domestic industry and many of them are incapable of feeding themselves without imports from the rest of the world (Russia is a notable exception). Some, such as Norway and a few of the smaller Gulf states, amassed enormous foreign reserves to protect themselves from price declines when times were good, but many did not, instead preferring to spend the temporary windfall on everything from military misadventures to experiments in “Bolivarian socialism”. As mentioned above, Brunei belongs to the latter group, with its expansive fiscal policy.

Furthermore, there are big differences between the impact of the oil price on government budgets in places that peg their currencies to the dollar, such as Saudia Arabia and the Gulf emirates, and places with floating currencies, such as Norway and Russia.

The below graph represents the distribution of the countries by breakeven oil price.

As it is made clear by the trend line, Norway has the lowest breakeven price, far below the average crude oil price; this means that the conservative policies during more favourable periods allowed the Norwegian economy to reduce its exposure to oil price movements, thus gaining a competitive advantage during negative macro trends. On the other hand, we find states that were unable to accumulate extra reserves, most probably due to a difficult political situation: that is the case of Libya, Colombia and Venezuela, whose breakeven prices are far above the average crude oil price. In the middle are all the other countries including Brunei, which actually needs just a little rise in the oil price to “fix” its current balance account.

In conclusion, while there is some skepticism among analysts about an active intervention by the government to address this issue, it is without doubt that such economic structure, heavily dependent on oil price, and the rising political tensions with neighbouring countries may lead to further internal troubles which could compel the government to undertake an expansive fiscal policy, thus further worsening the current balance account.

Mattia Migliardi