Shinzo Abe, despite scandals and challenges coming from his party, won the popular vote in Japan in an early election thus becoming a prime minister for another term. Central in his policies is the famous plan for reviving Japanese economy known as “Abenomics”, which seeks to improve GDP growth and push inflation rates up. Introduced in 2013, it consists of “three arrows” pointed at monetary policy, fiscal policy and growth strategy through structural reform.

The monetary policy consists of asset purchases conducted by the Bank of Japan (BoJ). With the usage of quantitative easing, BoJ increased the money supply, which introduced liquidity in the market. The first round of quantitative easing came in 2013; however, in 2017 inflation continued to stagnate below 1 percent, this prompted the Bank of Japan to begin a second round of quantitative easing, consisting of buying assets worth $660 billion every year until the target inflation of 2% is achieved. The value of the assets in possession of the Bank of Japan is more than 70% of Japan’s GDP, while, in comparison, the U.S. Federal Reserve holds less than 25% of the GDP. In addition, the Bank of Japan initiated negative interest rates in early 2016, so that they encourage lending and investment, similarly to Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. Some economists are worried that the low interest rates and the immense asset purchases can harm the banking system, and it has also been argued that the monetary easing can cause hyperinflation.

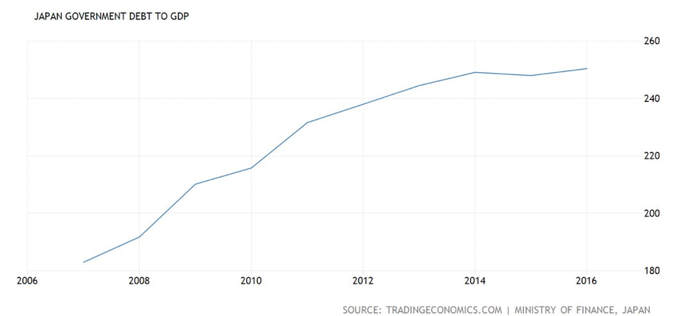

The fiscal policy began in 2013 with an economic recovery worth 20.2 trillion yen, equal to $210 billion, of which 10.3 trillion or $116 billion came straight from government spending. This big stimulus was primarily used for infrastructure projects, such as earthquake-resistant roads. Another 5.5 trillion yen and a 3.5 trillion yen followed in the next years, which increased Japan’s deficit spending. The International Monetary Fund has warned that the amount of Japanese debt is unhealthy for the economy.

The monetary policy consists of asset purchases conducted by the Bank of Japan (BoJ). With the usage of quantitative easing, BoJ increased the money supply, which introduced liquidity in the market. The first round of quantitative easing came in 2013; however, in 2017 inflation continued to stagnate below 1 percent, this prompted the Bank of Japan to begin a second round of quantitative easing, consisting of buying assets worth $660 billion every year until the target inflation of 2% is achieved. The value of the assets in possession of the Bank of Japan is more than 70% of Japan’s GDP, while, in comparison, the U.S. Federal Reserve holds less than 25% of the GDP. In addition, the Bank of Japan initiated negative interest rates in early 2016, so that they encourage lending and investment, similarly to Denmark, Sweden and Switzerland. Some economists are worried that the low interest rates and the immense asset purchases can harm the banking system, and it has also been argued that the monetary easing can cause hyperinflation.

The fiscal policy began in 2013 with an economic recovery worth 20.2 trillion yen, equal to $210 billion, of which 10.3 trillion or $116 billion came straight from government spending. This big stimulus was primarily used for infrastructure projects, such as earthquake-resistant roads. Another 5.5 trillion yen and a 3.5 trillion yen followed in the next years, which increased Japan’s deficit spending. The International Monetary Fund has warned that the amount of Japanese debt is unhealthy for the economy.

Last, the structural reform, which many argue is the key to successful “Abenomics”, contains corporate tax cuts, labor market changes, agricultural freedom, and programs to improve health care, education and energy usage.

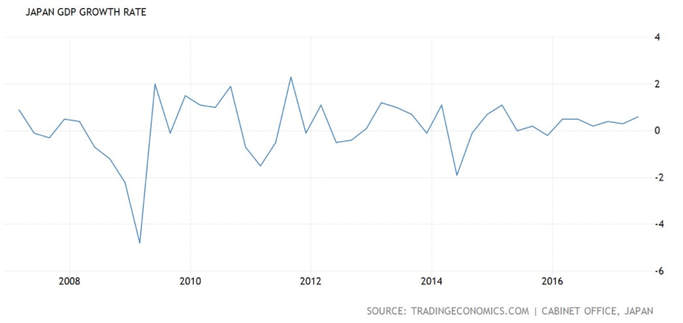

These policies have had positive effects on the economy, causing the IMF to call “Abenomics” a success. The monetary easing enabled access to credit, increasing investment and it has also led to a depreciation of the yen which generated a boost in exports. The GDP per capita also is increasing steadily. Large and small businesses are reporting steady profits under Abe’s government and business growth is also being supported by corporate tax cuts, agricultural reforms, the introduction of more and more women in the labor market and the inflows of foreign workers.

These policies have had positive effects on the economy, causing the IMF to call “Abenomics” a success. The monetary easing enabled access to credit, increasing investment and it has also led to a depreciation of the yen which generated a boost in exports. The GDP per capita also is increasing steadily. Large and small businesses are reporting steady profits under Abe’s government and business growth is also being supported by corporate tax cuts, agricultural reforms, the introduction of more and more women in the labor market and the inflows of foreign workers.

Even though positive outcomes have been seen, Shinzo Abe still is facing major challenges. Government spending has been enormous but growth is still dull, inflation is currently out of reach and there is an increased concern over the accumulated debt. Additionally, the Japanese economy went into recession in 2014 and, even though in the next two years it had growth of more than 1%, consumer prices fell. Sustained low unemployment below 3% and government stimulus have caused wages to go up, but their increase is slowing down and they have fallen in real terms during the last decade. Most experts think that unless consumer demand, prompted by higher wages, grows or there is a big demographic change, Japan will not be able to develop its economy as it wants.

As the prime minister pointed out, the aging population of Japan is “the biggest challenge” for his reforms. The people who were in the working age decreased by 6% in the last decade and Japan is expected to lose one third of its population in the upcoming 50 years. As an answer to this problem, Abe introduced a new plan which aims to raise the birth rate and increase social security. He invented a new cabinet job with the only purpose of shifting the demographic deterioration.

The government is also focusing on reforming the labor market in relation to women. The target is to increase the employment of females from 68% to 73% by 2020 and, to do so, it has forced firms to put women in management positions, with the mission being that females should hold 15% of top position by 2020. The state has said that raising women’s employment will also lead to an increase in the birth rate, with Sweden and Denmark serving as examples.

In order for Japan to maintain its growth, the productivity of businesses needs to improve and reforms in the labor market are to be done. A vital change is to abolish long and ineffective work hours, as well as to stimulate corporations to give rewards for good results. The government is also looking to solve the issue with midcareer hiring: nowadays companies can’t hire new midcareer workers because they can’t let go the old ones who will most likely have difficulty in finding a new job. Firms should have an incentive to regularly hire midcareer workers, so that this problem is solved.

In the coming years, the government will also focus on the economic inequality existing in Japan. Abe promised to make preschool and university free. He wants to enact rules which make the hourly pay between full time and part time workers the same, which would be very beneficial to women and young adults; furthermore, he also wishes to decrease the tax on workers with low-paying jobs.

Even though Japan has developed under the leadership of Shinzo Abe, there are still important problems to be dealt with. The government wishes to increase GDP, consumption, wages and capital investments but there are a few major challenges it must face first. The aging population, the inconsistent growth and the low inflation are all key issues which have to be addressed in the new term. On top of this, the crisis in North Korea is threatening the national security of Japan, which will probably hinder the economic advance hoped for; nevertheless, the government is still enacting needed reforms on several aspects of the economy and is being proactive in order to change Japan in the long run.

The government is also focusing on reforming the labor market in relation to women. The target is to increase the employment of females from 68% to 73% by 2020 and, to do so, it has forced firms to put women in management positions, with the mission being that females should hold 15% of top position by 2020. The state has said that raising women’s employment will also lead to an increase in the birth rate, with Sweden and Denmark serving as examples.

In order for Japan to maintain its growth, the productivity of businesses needs to improve and reforms in the labor market are to be done. A vital change is to abolish long and ineffective work hours, as well as to stimulate corporations to give rewards for good results. The government is also looking to solve the issue with midcareer hiring: nowadays companies can’t hire new midcareer workers because they can’t let go the old ones who will most likely have difficulty in finding a new job. Firms should have an incentive to regularly hire midcareer workers, so that this problem is solved.

In the coming years, the government will also focus on the economic inequality existing in Japan. Abe promised to make preschool and university free. He wants to enact rules which make the hourly pay between full time and part time workers the same, which would be very beneficial to women and young adults; furthermore, he also wishes to decrease the tax on workers with low-paying jobs.

Even though Japan has developed under the leadership of Shinzo Abe, there are still important problems to be dealt with. The government wishes to increase GDP, consumption, wages and capital investments but there are a few major challenges it must face first. The aging population, the inconsistent growth and the low inflation are all key issues which have to be addressed in the new term. On top of this, the crisis in North Korea is threatening the national security of Japan, which will probably hinder the economic advance hoped for; nevertheless, the government is still enacting needed reforms on several aspects of the economy and is being proactive in order to change Japan in the long run.

Dimana Tzonova