The Belt and Road Initiative is a massive China-led infrastructure project that aims to stretch around the globe. It is an effort to develop an expanded, interdependent market for China, grow China's economic and political power, and create the right conditions for China to build a high technology economy.

However, not all the BRI projects have been successful, and the initiatives have frequently relied too heavily on the backing of governments and policies. This led to a surging debt crises in developing countries, which found themselves in a “Debt Trap Diplomacy” and to China understanding it will be more and more difficult to have its money back.

Introduction and overview on China’s monetary policy

With the 2018 trade war against the US, its troubled housing market, the ongoing semiconductor battle, Taiwan tensions and its recent reopening of the economy, China has been consistently making headlines in the past half of the decade, and often, not for the best reasons.

Despite its government and leaders being under intense scrutiny, one crucial aspect that may have a solution for many of these problems tends to be overlooked. More specifically, China’s Central Bank, PBC (People’s Bank of China), and its stance on monetary policy, has had a significant impact on the economy, and can be credited in part for the rebound witnessed in the first quarter of 2023. Notwithstanding the success PBC registered in the last three months, its guiding policies, and underlying framework are far from flawless.

Governor’s Yi Gang approach to achieve a balance between economic growth and stability, prompted critics to argue that his policies are too prudent, bordering inefficiency. These concerns spur from the two subsequent 0.2% reductions in the policy rate after the covid-19 pandemic, and since the start of 2022.

The explanation between the 20 bps slashes in the policy rate are twofold. For one, the monetary framework in China gives very little freedom to its Central Bank to enact macroeconomic policies. The de facto decision-making body is the State Council, having the authority to set the target rate. Thus, the PBC becomes only a counsel in matters of monetary policy, even though its advice is usually followed during SC meetings. This institutional setup has its drawbacks, yet it allows great coordination between fiscal and monetary policies, ensuring that any potential reform has a consolidating effect, rather than an ambiguous one.

The other reason for the cautious changes in the policy rate has been explained by Mr. Yi, stating that he is following Phelps’ “golden rule” of saving and investment, which implies that in a healthy economy, the interest rate should equal the potential growth rate. Interest rates aren’t the only tool at the Central Bank’s disposal to encourage the growth of the real economy. To this end, the RRR (reserve requirement ratios) have been cut several times from their 2018 value of 15%, now sitting at under 8%. Tweaking the RRR provides long-term liquidity without flooding the economy, and exacerbating the consequences of expansionary policies.

In a news conference Yi Gang stated that “The PBC will provide ‘forceful’ financial support for the stable and healthy development of the economy”. Therefore, even though the world’s second largest economy has been heavily affected by isolationist policies, and trade restrictions, it managed to achieve a promising economic growth in the first quarter of 2023, putting the country on track to meet its rather modest 5.5% 2023 target. The comeback can be mostly credited to the export and retail sector. Exports expanded by nearly 15% in March, largely due to a spike in electric cars demand, while retail sales saw a 10.6% increase, far exceeding analysts’ expectations. The growth has been offset by woes in property and unemployment, but it may keep its momentum throughout Q2. Uncertainty arises due to the superpower’s reliance on external demand. With an almost impending recession in the US and with Europe battling double-digit inflation, and ever-increasing rates, the demand for China’s exports may slump, and thus negate the key driver of its economic recovery. This extenuates the importance of bolstering its domestic market, and economy.

A new project: Belt and Road Initiative

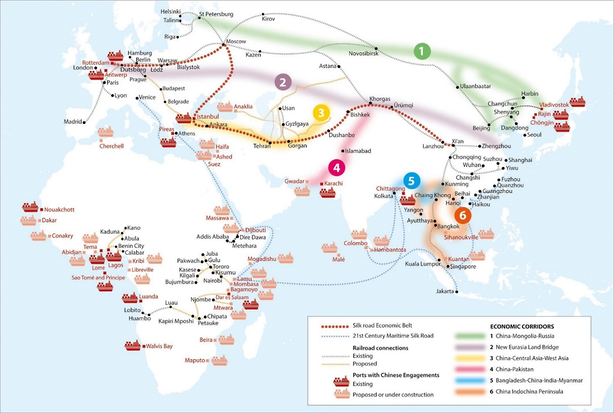

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, has been an incredibly ambitious infrastructure project since its launch in 2013 by President Xi Jinping. Originally designed to link East Asia and Europe through physical infrastructure, the project has since expanded to six main economic corridors, including China and Mongolia and Russia, Eurasian countries, Central and West Asia, Pakistan, other countries in the Indian sub-continent, and Indochina. This expansion has significantly broadened China’s economic and political influence.

President Xi announced the initiative during official visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013, unveiling a two-pronged plan comprised of the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road.

However, not all the BRI projects have been successful, and the initiatives have frequently relied too heavily on the backing of governments and policies. This led to a surging debt crises in developing countries, which found themselves in a “Debt Trap Diplomacy” and to China understanding it will be more and more difficult to have its money back.

Introduction and overview on China’s monetary policy

With the 2018 trade war against the US, its troubled housing market, the ongoing semiconductor battle, Taiwan tensions and its recent reopening of the economy, China has been consistently making headlines in the past half of the decade, and often, not for the best reasons.

Despite its government and leaders being under intense scrutiny, one crucial aspect that may have a solution for many of these problems tends to be overlooked. More specifically, China’s Central Bank, PBC (People’s Bank of China), and its stance on monetary policy, has had a significant impact on the economy, and can be credited in part for the rebound witnessed in the first quarter of 2023. Notwithstanding the success PBC registered in the last three months, its guiding policies, and underlying framework are far from flawless.

Governor’s Yi Gang approach to achieve a balance between economic growth and stability, prompted critics to argue that his policies are too prudent, bordering inefficiency. These concerns spur from the two subsequent 0.2% reductions in the policy rate after the covid-19 pandemic, and since the start of 2022.

The explanation between the 20 bps slashes in the policy rate are twofold. For one, the monetary framework in China gives very little freedom to its Central Bank to enact macroeconomic policies. The de facto decision-making body is the State Council, having the authority to set the target rate. Thus, the PBC becomes only a counsel in matters of monetary policy, even though its advice is usually followed during SC meetings. This institutional setup has its drawbacks, yet it allows great coordination between fiscal and monetary policies, ensuring that any potential reform has a consolidating effect, rather than an ambiguous one.

The other reason for the cautious changes in the policy rate has been explained by Mr. Yi, stating that he is following Phelps’ “golden rule” of saving and investment, which implies that in a healthy economy, the interest rate should equal the potential growth rate. Interest rates aren’t the only tool at the Central Bank’s disposal to encourage the growth of the real economy. To this end, the RRR (reserve requirement ratios) have been cut several times from their 2018 value of 15%, now sitting at under 8%. Tweaking the RRR provides long-term liquidity without flooding the economy, and exacerbating the consequences of expansionary policies.

In a news conference Yi Gang stated that “The PBC will provide ‘forceful’ financial support for the stable and healthy development of the economy”. Therefore, even though the world’s second largest economy has been heavily affected by isolationist policies, and trade restrictions, it managed to achieve a promising economic growth in the first quarter of 2023, putting the country on track to meet its rather modest 5.5% 2023 target. The comeback can be mostly credited to the export and retail sector. Exports expanded by nearly 15% in March, largely due to a spike in electric cars demand, while retail sales saw a 10.6% increase, far exceeding analysts’ expectations. The growth has been offset by woes in property and unemployment, but it may keep its momentum throughout Q2. Uncertainty arises due to the superpower’s reliance on external demand. With an almost impending recession in the US and with Europe battling double-digit inflation, and ever-increasing rates, the demand for China’s exports may slump, and thus negate the key driver of its economic recovery. This extenuates the importance of bolstering its domestic market, and economy.

A new project: Belt and Road Initiative

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), sometimes referred to as the New Silk Road, has been an incredibly ambitious infrastructure project since its launch in 2013 by President Xi Jinping. Originally designed to link East Asia and Europe through physical infrastructure, the project has since expanded to six main economic corridors, including China and Mongolia and Russia, Eurasian countries, Central and West Asia, Pakistan, other countries in the Indian sub-continent, and Indochina. This expansion has significantly broadened China’s economic and political influence.

President Xi announced the initiative during official visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013, unveiling a two-pronged plan comprised of the overland Silk Road Economic Belt and the Maritime Silk Road.

OECD research from multiple sources, including: HKTDC, MERICS, Belt and Road Center, Foreign Policy, The Diplomat, Silk Routes, State Council Information Office of the People’s Republic of China, WWF Hong Kong (China).

Since then, 149 countries, accounting for two-thirds of the world's population and 40% of global GDP, have signed on to BRI projects or expressed interest in doing so.

The BRI aims to create a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and streamlined border crossings, expand the international use of Chinese currency, and create jobs through the funding of hundreds of special economic zones.

The estimated investment in BRI ranges from US$1 trillion to US$8 trillion, with the largest investments being in energy and transport infrastructure. The wide range in part reflects the undefined scope of the initiative, but also the limited data availability on the number, size, and terms of the projects.

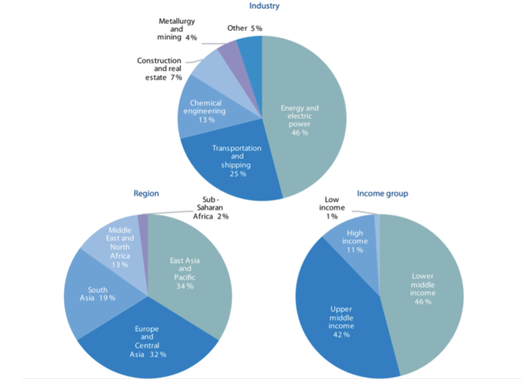

The BRI's largest investments are in the energy sector, with the total investment in transport infrastructure estimated to be US$144 billion. The energy and transport industries account for 71% of the total costs of the project. Two-thirds of the identified financing is expected to go to countries in East Asia and Pacific and Europe and Central Asia, with the remainder mainly to South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, and only 2% to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the financing will be received by lower- and upper-middle-income countries, with only 1% going to low-income and 11% to high-income economies. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association-eligible countries are expected to receive most of the investment, with US$525 billion or 91% of the total share. Most of the BRI investment is in the construction or planning phase, with only US$66 billion going to completed projects by the end of 2016.

The BRI aims to create a vast network of railways, energy pipelines, highways, and streamlined border crossings, expand the international use of Chinese currency, and create jobs through the funding of hundreds of special economic zones.

The estimated investment in BRI ranges from US$1 trillion to US$8 trillion, with the largest investments being in energy and transport infrastructure. The wide range in part reflects the undefined scope of the initiative, but also the limited data availability on the number, size, and terms of the projects.

The BRI's largest investments are in the energy sector, with the total investment in transport infrastructure estimated to be US$144 billion. The energy and transport industries account for 71% of the total costs of the project. Two-thirds of the identified financing is expected to go to countries in East Asia and Pacific and Europe and Central Asia, with the remainder mainly to South Asia and the Middle East and North Africa, and only 2% to Sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of the financing will be received by lower- and upper-middle-income countries, with only 1% going to low-income and 11% to high-income economies. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development and International Development Association-eligible countries are expected to receive most of the investment, with US$525 billion or 91% of the total share. Most of the BRI investment is in the construction or planning phase, with only US$66 billion going to completed projects by the end of 2016.

BRI investments in Belt and Road corridor economies, Source: Bandiera and Tsiropoulos 2019.

The BRI is driven by both geopolitical and economic motivations of China. President Xi has emphasized the need for China to be more assertive, even as the country's outstanding loans have grown to over a quarter of its GDP. The BRI serves as a way to develop new trade linkages, cultivate export markets, increase Chinese incomes, and address China's excess

productive capacity.

China's leaders are determined to restructure the economy and avoid the middle-income trap, which has affected around 90% of middle-income countries since 1960, where wages and quality of life improve as low-skilled manufacturing rises, but countries struggle to shift to producing higher-value goods and services.

However, the BRI has faced challenges in the past three years, with more than $78 billions of borrowing turning sour and leading to renegotiations or write-offs of loans from Chinese institutions between 2020 and the end of March this year.

China has provided an unprecedented amount of "rescue loans" to prevent sovereign defaults by large borrowers among the 150 countries that have joined the BRI. These sovereign bailouts amounted to $104 billion between 2019 and the end of 2021. Nonetheless, many BRI borrowing countries are on the verge of insolvency due to a slowdown in global growth, increasing interest

rates, and record-high debt levels in the developing world. Western creditors of these countries have accused China of obstructing debt restructuring negotiations. Despite these challenges, the BRI continues to be a vital part of China's geopolitical and economic strategy.

Focus on interest rates: Alternatives for developing countries and conflicts with IMF

As previously discussed, the current macroeconomic environment with the Ukrainian War and a strong dollar have significantly impacted the ability of the borrowing countries to repay their debts. Consequently, China has reduced its issuance of loans in the last couple of years. China’s net transfers to developing countries has turned negative in 2019, effectively transforming China into a world debt collector. Since then, China has been actively rescuing distressed debtor countries with bailouts. These rescue loans amount to more than 100 billion dollars in just the last 4 years and they represent a substantial change for China from their previous role as an infrastructure lender. China’s approach to bailout lending is different to other countries. Typically, a distressed country would rely on the Paris Club, an informal group of creditor countries that finds solutions to payment problems by debtor nations. This whole process is mediated by the IMF and usually involves some form of debt relief. China is not part of the Paris Club and demands the payments to be paid in full. As a consequence, this creates friction because the countries that belong to the Paris Club are less willing to offer debt relief if they know that this “discount” is going straight to China’s pockets. This lack of coordination among creditors is considered one of the causes of prolonged crises in Countries such as Sri Lanka and Zambia. On top of this coordination problem caused by China’s aversion to grant write-offs, there are other major differences between China’s bailouts and the IMF program. The main one to consider is that China’s loans are not cheap. A typical rescue loan from the IMF carries a 2% interest, while China’s one is around 5%. What is also clear is that China mainly offers these bailouts to countries to which it is more exposed. According to Carmen Reinhart, the author of a study on these loans, “Beijing is ultimately trying to rescue its own banks”. Lending money to debt distressed countries is not a bad idea per se. However, an important premise is that the infrastructures financed with these loans grant higher benefits than their costs. With China’s money this was not always the case. In fact, the Belt and Road initiative had some great projects, but also some terrible ones. The list of the latter includes a 1-billion-dollar bridge in Montenegro, which makes it one of the most expensive projects of this kind in the world, with doubtful benefits for the overall country. Other disastrous projects include unused stadiums, airports and ports in Asia, a 1150-feet tall Lotus tower in Sri Lanka and many more. These are the kind of failures that, tied with a lot of money lost due to corruption, made it impossible for some countries to repay their loans. This is where China’s bailouts come in hand, but their help is more beneficial to Beijing than to the borrowing countries.

A phenomenon that we are seeing in the last few years is that the swap line provided by China has become progressively important for overseas crisis management. Although they were put in place in 2008, they went basically unused for more than a decade. These swap lines have the adverse effect of making China’s operations even more opaque. The reason for that is that, technically, they are short-term repayment agreements with maturities of 3-12 months. This characteristic makes them fall outside most international debt disclosure requirements. However, borrowers are allowed to roll them over, effectively repaying them only after 3 and a half years.

The use of these swap lines (denominated in renminbi of course) is important not only for China or the borrowing countries, but for the whole world too. Their use further increases the adoptance of renminbi in trade, which is a phenomenon we are seeing in other aspects of the economy.

The trap

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) employs a strategy of 'debt-trap diplomacy.' This approach allegedly involves enticing poor, developing nations to accept unsustainable loans in order to pursue infrastructure projects, with the aim of seizing assets and extending military or strategic reach in the event of financial difficulties. Chinese loans, whether they are concessional or commercial, are usually provided by Chinese banks, and only involve China and the borrowing country. In fact, in more than one hundred debt financing contracts signed by China with foreign governments, the agreements often include clauses that restrict restructuring with the “Paris Club." Additionally, China often retains the right to demand repayment at any time, which gives Beijing the ability to use

funding as a tool to enforce Chinese interests, such as those related to Taiwan or the treatment of Uyghurs.

Conclusions

Amidst the current environment of economic uncertainty with rising interest rates and tensions between China and the US, the situation surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become problematic. Economic difficulties have made it challenging for developing countries to repay their debts, while China has been reducing loans to low-income countries and dealing with non-performing loans. According to economists Sebastian Horn, Carmen Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, 60% of China's overseas loans are now held by financially distressed countries, compared to just 5% in 2010. Presently, China is collaborating with other creditors to

tackle debt issues, including coordinating with the Group of 20 for debt relief and extensions in some countries. It is important to note that the BRI is a long-term initiative and, as we mentioned before, China sees it as a crucial part of its foreign policy and global strategy.

Therefore, it is unlikely that China will completely retreat from the initiative. Moving forward, it will be important to monitor how China manages the debt issues and works with other countries to promote the BRI. Additionally, the global economic environment, including rising interest rates, will also have an impact on the success of the initiative.

The topic is still young and new studies need to be made to assess the effectiveness of China’s

global interventions.

By Elena Di Ceglie, Yuxi Cheng, Enrico Dametto, Vittoria Palmieri and Matei Sandru

SOURCES:

• The Economist

• Financial Times

• IMF

• Reuters

• CNBC

• OECD

• WorldBank

• WSJ

productive capacity.

China's leaders are determined to restructure the economy and avoid the middle-income trap, which has affected around 90% of middle-income countries since 1960, where wages and quality of life improve as low-skilled manufacturing rises, but countries struggle to shift to producing higher-value goods and services.

However, the BRI has faced challenges in the past three years, with more than $78 billions of borrowing turning sour and leading to renegotiations or write-offs of loans from Chinese institutions between 2020 and the end of March this year.

China has provided an unprecedented amount of "rescue loans" to prevent sovereign defaults by large borrowers among the 150 countries that have joined the BRI. These sovereign bailouts amounted to $104 billion between 2019 and the end of 2021. Nonetheless, many BRI borrowing countries are on the verge of insolvency due to a slowdown in global growth, increasing interest

rates, and record-high debt levels in the developing world. Western creditors of these countries have accused China of obstructing debt restructuring negotiations. Despite these challenges, the BRI continues to be a vital part of China's geopolitical and economic strategy.

Focus on interest rates: Alternatives for developing countries and conflicts with IMF

As previously discussed, the current macroeconomic environment with the Ukrainian War and a strong dollar have significantly impacted the ability of the borrowing countries to repay their debts. Consequently, China has reduced its issuance of loans in the last couple of years. China’s net transfers to developing countries has turned negative in 2019, effectively transforming China into a world debt collector. Since then, China has been actively rescuing distressed debtor countries with bailouts. These rescue loans amount to more than 100 billion dollars in just the last 4 years and they represent a substantial change for China from their previous role as an infrastructure lender. China’s approach to bailout lending is different to other countries. Typically, a distressed country would rely on the Paris Club, an informal group of creditor countries that finds solutions to payment problems by debtor nations. This whole process is mediated by the IMF and usually involves some form of debt relief. China is not part of the Paris Club and demands the payments to be paid in full. As a consequence, this creates friction because the countries that belong to the Paris Club are less willing to offer debt relief if they know that this “discount” is going straight to China’s pockets. This lack of coordination among creditors is considered one of the causes of prolonged crises in Countries such as Sri Lanka and Zambia. On top of this coordination problem caused by China’s aversion to grant write-offs, there are other major differences between China’s bailouts and the IMF program. The main one to consider is that China’s loans are not cheap. A typical rescue loan from the IMF carries a 2% interest, while China’s one is around 5%. What is also clear is that China mainly offers these bailouts to countries to which it is more exposed. According to Carmen Reinhart, the author of a study on these loans, “Beijing is ultimately trying to rescue its own banks”. Lending money to debt distressed countries is not a bad idea per se. However, an important premise is that the infrastructures financed with these loans grant higher benefits than their costs. With China’s money this was not always the case. In fact, the Belt and Road initiative had some great projects, but also some terrible ones. The list of the latter includes a 1-billion-dollar bridge in Montenegro, which makes it one of the most expensive projects of this kind in the world, with doubtful benefits for the overall country. Other disastrous projects include unused stadiums, airports and ports in Asia, a 1150-feet tall Lotus tower in Sri Lanka and many more. These are the kind of failures that, tied with a lot of money lost due to corruption, made it impossible for some countries to repay their loans. This is where China’s bailouts come in hand, but their help is more beneficial to Beijing than to the borrowing countries.

A phenomenon that we are seeing in the last few years is that the swap line provided by China has become progressively important for overseas crisis management. Although they were put in place in 2008, they went basically unused for more than a decade. These swap lines have the adverse effect of making China’s operations even more opaque. The reason for that is that, technically, they are short-term repayment agreements with maturities of 3-12 months. This characteristic makes them fall outside most international debt disclosure requirements. However, borrowers are allowed to roll them over, effectively repaying them only after 3 and a half years.

The use of these swap lines (denominated in renminbi of course) is important not only for China or the borrowing countries, but for the whole world too. Their use further increases the adoptance of renminbi in trade, which is a phenomenon we are seeing in other aspects of the economy.

The trap

China's Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) employs a strategy of 'debt-trap diplomacy.' This approach allegedly involves enticing poor, developing nations to accept unsustainable loans in order to pursue infrastructure projects, with the aim of seizing assets and extending military or strategic reach in the event of financial difficulties. Chinese loans, whether they are concessional or commercial, are usually provided by Chinese banks, and only involve China and the borrowing country. In fact, in more than one hundred debt financing contracts signed by China with foreign governments, the agreements often include clauses that restrict restructuring with the “Paris Club." Additionally, China often retains the right to demand repayment at any time, which gives Beijing the ability to use

funding as a tool to enforce Chinese interests, such as those related to Taiwan or the treatment of Uyghurs.

Conclusions

Amidst the current environment of economic uncertainty with rising interest rates and tensions between China and the US, the situation surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) has become problematic. Economic difficulties have made it challenging for developing countries to repay their debts, while China has been reducing loans to low-income countries and dealing with non-performing loans. According to economists Sebastian Horn, Carmen Reinhart, and Christoph Trebesch, 60% of China's overseas loans are now held by financially distressed countries, compared to just 5% in 2010. Presently, China is collaborating with other creditors to

tackle debt issues, including coordinating with the Group of 20 for debt relief and extensions in some countries. It is important to note that the BRI is a long-term initiative and, as we mentioned before, China sees it as a crucial part of its foreign policy and global strategy.

Therefore, it is unlikely that China will completely retreat from the initiative. Moving forward, it will be important to monitor how China manages the debt issues and works with other countries to promote the BRI. Additionally, the global economic environment, including rising interest rates, will also have an impact on the success of the initiative.

The topic is still young and new studies need to be made to assess the effectiveness of China’s

global interventions.

By Elena Di Ceglie, Yuxi Cheng, Enrico Dametto, Vittoria Palmieri and Matei Sandru

SOURCES:

• The Economist

• Financial Times

• IMF

• Reuters

• CNBC

• OECD

• WorldBank

• WSJ