In May 2022, Sri Lanka officially defaulted, missing an interest payment on its foreign debt for the first time in its history. The country has been hit by a severe economic crisis since 2019. Many experts considered China among the causes of the country’s debt distress due to its debt-trap diplomacy and predatory lending policies. Indeed, China has expanded its external lending to developing countries in the last few years, especially by investing in infrastructure projects. According to some policymakers, this is just a means for China to extend its influence over these countries. Using the example of the Sri Lankan debt crisis, we will assess to what extent this claim can be considered valid.

China’s Debt Trap: an Overview

The so-called ‘debt trap’ diplomacy is a specific type of lending policy when the lender provides credit to the borrower country, motivated primarily by political leverage rather than financial gains. China is being accused more and more often of applying this lending policy. However, Beijing denies these accusations and states that these rumors are only spread by Western policymakers.

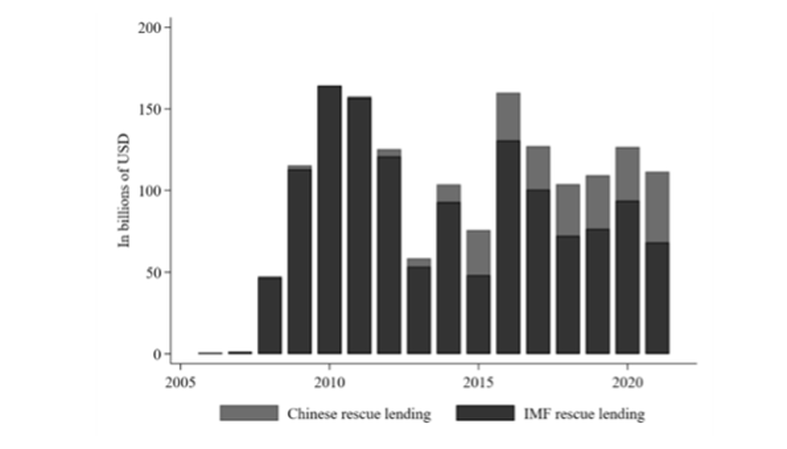

In any case, according to the World Bank, China has become the single largest lender entity in the last ten-to-fifteen years, overtaking institutions such as IMF or the World Bank in terms of aggregate external public debt. Most of this debt – almost half of it – is owed by low- and middle-income countries, with two-thirds located in Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. The amount of money lent to low- and middle-income countries by China approximately quadrupled in the last decade, from $40 bn in 2010 to roughly $170 bn in 2020. Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, and Zambia have debts owed to China that amount to more than 40% of their annual GDP, while more than 40 countries have at least 10%, which is certainly remarkable.

The so-called ‘debt trap’ diplomacy is a specific type of lending policy when the lender provides credit to the borrower country, motivated primarily by political leverage rather than financial gains. China is being accused more and more often of applying this lending policy. However, Beijing denies these accusations and states that these rumors are only spread by Western policymakers.

In any case, according to the World Bank, China has become the single largest lender entity in the last ten-to-fifteen years, overtaking institutions such as IMF or the World Bank in terms of aggregate external public debt. Most of this debt – almost half of it – is owed by low- and middle-income countries, with two-thirds located in Sub-Saharan Africa or South Asia. The amount of money lent to low- and middle-income countries by China approximately quadrupled in the last decade, from $40 bn in 2010 to roughly $170 bn in 2020. Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, and Zambia have debts owed to China that amount to more than 40% of their annual GDP, while more than 40 countries have at least 10%, which is certainly remarkable.

In 2013, The People's Republic of China launched the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a worldwide infrastructure growth plan. Through the construction of transportation infrastructure such as highways, railroads, ports, airports, energy pipes, and telecom networks, China is meant to promote globalization and foster trade. As suggested by the name, the BRI has two main categories for its infrastructure: the "Belt" and the "Road". The "Belt" represents all the land-based points, such as the Silk Road. Thus, through the land-based initiative, China aims to bring back and expand upon the historic trade routes that used to link China to Europe and Central Asia. And the "Road" represents the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road, which seeks to increase maritime trade between China, Southeast Asia, Africa, and Europe. Together, these two components make up the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese plan to build, and perhaps dominate a global trade network. This is a primary example of the growing influence of China on the economy of developing countries.

However, according to AidData (an international development body at William & Mary University), estimating the impact of these kinds of measures correctly is problematic because a significant proportion of what China lends to developing countries is not reported by them. Indeed, most loans run through various financial institutions and entities and include a non-disclosure agreement; hence, it is complicated to guess the exact number.

Based on the prevailing allegations, the typical Chinese debt trap works as follows. China lends a massive amount of money to a developing country, usually for a vast infrastructure project by the borrower’s standards - for example, motorways, bridges, ports, or railways. In most cases, these Chinese loans are more expensive, with higher interest rates than the ones from other governments or the ones from the World Bank, for example. Being more costly and the typically shorter repayment period make it generally harder to meet the repayment conditions for these loans, and that is when the debt becomes a trap. In most of these cases, if the borrower defaults and fails to pay the loan, the creditor, China, is eligible to seize critical assets in the borrower’s country. These can even be strategically and politically vital assets. Beijing denies the existence and use of this concept and says it only fulfills a need for developing countries struggling to finance their infrastructure and development projects.

A country that was indeed affected greatly by the Chinese debt trap is Sri Lanka, which we will analyze more in detail in the following paragraphs.

However, according to AidData (an international development body at William & Mary University), estimating the impact of these kinds of measures correctly is problematic because a significant proportion of what China lends to developing countries is not reported by them. Indeed, most loans run through various financial institutions and entities and include a non-disclosure agreement; hence, it is complicated to guess the exact number.

Based on the prevailing allegations, the typical Chinese debt trap works as follows. China lends a massive amount of money to a developing country, usually for a vast infrastructure project by the borrower’s standards - for example, motorways, bridges, ports, or railways. In most cases, these Chinese loans are more expensive, with higher interest rates than the ones from other governments or the ones from the World Bank, for example. Being more costly and the typically shorter repayment period make it generally harder to meet the repayment conditions for these loans, and that is when the debt becomes a trap. In most of these cases, if the borrower defaults and fails to pay the loan, the creditor, China, is eligible to seize critical assets in the borrower’s country. These can even be strategically and politically vital assets. Beijing denies the existence and use of this concept and says it only fulfills a need for developing countries struggling to finance their infrastructure and development projects.

A country that was indeed affected greatly by the Chinese debt trap is Sri Lanka, which we will analyze more in detail in the following paragraphs.

The Causes of the Sri Lankan Debt Crisis

In April of last year, Sri Lanka’s debt default was announced. This triggered rolling blackouts, fuel queues, and street protests. The root causes of the country’s debt problem have been attributed to various factors, including corruption and nepotism, alleged predatory lending from China, and a structural balance of payments deficit. This imbalance has been fueled by improper use of public funds, and wasteful government spending, which has also contributed to the increase in borrowing to make up for the gap. However, it is clear that the immediate cause of Sri Lanka’s collapse is the structure of the country’s debt itself – specifically, its deep and growing exposure to international sovereign bonds (ISBs) issued at high-interest rates. In the immediate aftermath of Sri Lanka’s civil war in 2009, the country embarked on a mainly bilaterally financed infrastructure investment program. However, alongside these borrowings for investments in ports, energy, and transport, the Sri Lankan government also binged on international sovereign bonds, issuing $17 bn worth of ISBs from 2007 to 2019, in face value terms. Sri Lanka’s ISBs were issued at high coupon rates (often between 5-8%), with 36% of these ISBs being subject to classic collective action clauses. Typically, they are not linked to projects and therefore do not produce a corresponding asset or economic growth, nor is there much transparency on how the government budgets and spends funds accrued from these bonds. And the bondholders themselves comprise a diverse set of interests that are difficult to coordinate to negotiate a debt restructuring. As a result of this debt-fueled growth strategy (or lack thereof), the country’s ratio of public external debt stock to GDP grew from 29% in 2010 to 44% in 2021.

From a historical point of view, the outcome of the development strategy of Sri Lanka during the past eight decades has been labeled as a ‘twin deficit economy’, that is, an economy having both a current account deficit and a budget deficit. This means that the country experienced a persistent deficit in the current account of the balance of payment because domestic expenditure continuously exceeded domestic production together with a budget deficit.

Until the late 1970s, the government managed to keep deficits within a manageable range with grants and institutional borrowing. A substantial accumulation of external debt gained momentum after the liberalization reforms and from the emphasis on infrastructure investment following the end of the civil war.

In April of last year, Sri Lanka’s debt default was announced. This triggered rolling blackouts, fuel queues, and street protests. The root causes of the country’s debt problem have been attributed to various factors, including corruption and nepotism, alleged predatory lending from China, and a structural balance of payments deficit. This imbalance has been fueled by improper use of public funds, and wasteful government spending, which has also contributed to the increase in borrowing to make up for the gap. However, it is clear that the immediate cause of Sri Lanka’s collapse is the structure of the country’s debt itself – specifically, its deep and growing exposure to international sovereign bonds (ISBs) issued at high-interest rates. In the immediate aftermath of Sri Lanka’s civil war in 2009, the country embarked on a mainly bilaterally financed infrastructure investment program. However, alongside these borrowings for investments in ports, energy, and transport, the Sri Lankan government also binged on international sovereign bonds, issuing $17 bn worth of ISBs from 2007 to 2019, in face value terms. Sri Lanka’s ISBs were issued at high coupon rates (often between 5-8%), with 36% of these ISBs being subject to classic collective action clauses. Typically, they are not linked to projects and therefore do not produce a corresponding asset or economic growth, nor is there much transparency on how the government budgets and spends funds accrued from these bonds. And the bondholders themselves comprise a diverse set of interests that are difficult to coordinate to negotiate a debt restructuring. As a result of this debt-fueled growth strategy (or lack thereof), the country’s ratio of public external debt stock to GDP grew from 29% in 2010 to 44% in 2021.

From a historical point of view, the outcome of the development strategy of Sri Lanka during the past eight decades has been labeled as a ‘twin deficit economy’, that is, an economy having both a current account deficit and a budget deficit. This means that the country experienced a persistent deficit in the current account of the balance of payment because domestic expenditure continuously exceeded domestic production together with a budget deficit.

Until the late 1970s, the government managed to keep deficits within a manageable range with grants and institutional borrowing. A substantial accumulation of external debt gained momentum after the liberalization reforms and from the emphasis on infrastructure investment following the end of the civil war.

We can see that Sri Lanka entered the COVID-19 pandemic with a significant external debt overhang and the onset of the pandemic in March 2020 compounded the debt distress, with the biggest blow to the balance of payments being the collapse of tourism inflows. The government likely viewed the crisis as a temporary liquidity shock resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic while ignoring the systemic ‘solvency’ challenge.

The ISB Debt Trap

Looking at one of the most visible causes of the Sri Lanka debt crisis, we can analyze the dangerous mechanism of excessive international sovereign borrowing. In fact, for underdeveloped countries like Sri Lanka, borrowing from international capital markets is exceptionally risky.

In 2021, the ISB share of Sri Lanka’s external debt stock reached 36% and accounted for 70% of the government’s annual interest payments. Additionally, the bonds themselves are tradable and their prices are affected by the decisions of credit rating agencies. When credit rating agencies downgrade a country, the price of that country’s bonds decreases and its yield rises, making future borrowing more expensive. This can lead to a snowball effect in which a country takes on more debt at higher interest rates to pay back outstanding obligations (borrowed at lower rates). This means that the higher the share of ISBs in outstanding debt, the greater the annual interest paid.

The high level of ISB interest payments tends to exacerbate stresses from external and cyclical shocks, which underdeveloped countries are vulnerable to. We can see then how high-interest borrowing from international capital markets can eat into the foreign currency cash flows of a country, especially when it is wracked by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and conflict in Ukraine.

Looking at one of the most visible causes of the Sri Lanka debt crisis, we can analyze the dangerous mechanism of excessive international sovereign borrowing. In fact, for underdeveloped countries like Sri Lanka, borrowing from international capital markets is exceptionally risky.

In 2021, the ISB share of Sri Lanka’s external debt stock reached 36% and accounted for 70% of the government’s annual interest payments. Additionally, the bonds themselves are tradable and their prices are affected by the decisions of credit rating agencies. When credit rating agencies downgrade a country, the price of that country’s bonds decreases and its yield rises, making future borrowing more expensive. This can lead to a snowball effect in which a country takes on more debt at higher interest rates to pay back outstanding obligations (borrowed at lower rates). This means that the higher the share of ISBs in outstanding debt, the greater the annual interest paid.

The high level of ISB interest payments tends to exacerbate stresses from external and cyclical shocks, which underdeveloped countries are vulnerable to. We can see then how high-interest borrowing from international capital markets can eat into the foreign currency cash flows of a country, especially when it is wracked by external shocks such as the COVID-19 pandemic and conflict in Ukraine.

A Specific Example: Hambantota’s Harbour

In 2007, in order to build a new deep-water port in Hambantota, in the southern region of the country, Sri Lanka obtained a $1 billion loan from China. This project can be considered part of the Belt and Road Initiative described at the beginning. The port was designed to act as a major hub for trade and shipping in the Indian Ocean, considering Sri Lanka’s strategic position for trade. Indeed, the country is situated at the intersection of several important Indian Ocean trade lanes Sri Lanka is nicely situated close to India's southernmost point, in the middle of the east-west maritime lane that links Asia's expanding markets with those in EMEA. However, the project was met with major obstacles right away. The port failed to draw the expected volume of trade, leaving Sri Lanka with a heavy debt load and a neglected infrastructure. As part of a 99-year debt-for-equity swap, the Sri Lankan government gave China Merchants Port Holdings, a state-owned Chinese corporation, significant control of the Hambantota port in 2017. Under the agreement, Sri Lanka kept a 30% stake in the port while China Merchants Port Holdings obtained the majority of 70%, thus getting direct opportunities to extend its sphere of influence into Africa.

Public opinions on the matter differ to a large degree. Those who oppose the strategy say that the Chinese lending practices were an intentional effort to seize strategic influence over a vital harbor in a geopolitically vulnerable area. The Hambantota port is a critical component of China's "string of pearls" plan, which aims to build a network of infrastructure across the Indian Ocean to promote commerce, increase China's geopolitical power in the area, and thus global influence. On the contrary, according to supporters of China's lending policies, the Hambantota port was merely an instance of a poorly planned enterprise that failed to draw the type of business it required to be fiscally viable, portraying China as an ‘ethical’ investor, simply looking to make long-term profits. They make the argument that Sri Lanka's debt issues are not exclusively a product of Chinese lending by pointing out how the country has borrowed money from some other foreign lenders in addition to China.

For instance, to fund its building projects, such as highways, ports, and power plants, the nation has drawn heavily from foreign creditors, including global institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and private creditors. The Sri Lankan rupee's decline against other major currencies, caused by the failure to raise significant profits from these initiatives, has made it increasingly difficult for the nation to meet its debt commitments. Poor fiscal management and administration problems have also worsened Sri Lanka's debt struggles. The nation's finances have been further strained by ineffective changes in revenue maximization strategies across major producers of the region and weak tax collection methods. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has also made the Sri Lankan financial problem more severe, as we mentioned in the previous paragraph.

In order to handle the Sri Lankan debt crisis, the government has taken some steps, including approaching foreign financial organizations like the IMF for help with debt restructuring. Unfortunately, the Sri Lankan people's living standards have been further affected by these measures' strict requirements, which include austerity measures, a cut in benefits coming from fiscal spending, and general systemic changes. And China remains a significant investor in Sri Lanka despite the disagreements regarding the Hambantota port project, thereby rendering investments in sectors like infrastructure, energy, and tourism. The government of Sri Lanka has made an effort to find a compromise between luring Chinese investment and steering away from the kinds of debt burdens that have been affecting other nations within the region or simply under the Chinese investment.

In 2007, in order to build a new deep-water port in Hambantota, in the southern region of the country, Sri Lanka obtained a $1 billion loan from China. This project can be considered part of the Belt and Road Initiative described at the beginning. The port was designed to act as a major hub for trade and shipping in the Indian Ocean, considering Sri Lanka’s strategic position for trade. Indeed, the country is situated at the intersection of several important Indian Ocean trade lanes Sri Lanka is nicely situated close to India's southernmost point, in the middle of the east-west maritime lane that links Asia's expanding markets with those in EMEA. However, the project was met with major obstacles right away. The port failed to draw the expected volume of trade, leaving Sri Lanka with a heavy debt load and a neglected infrastructure. As part of a 99-year debt-for-equity swap, the Sri Lankan government gave China Merchants Port Holdings, a state-owned Chinese corporation, significant control of the Hambantota port in 2017. Under the agreement, Sri Lanka kept a 30% stake in the port while China Merchants Port Holdings obtained the majority of 70%, thus getting direct opportunities to extend its sphere of influence into Africa.

Public opinions on the matter differ to a large degree. Those who oppose the strategy say that the Chinese lending practices were an intentional effort to seize strategic influence over a vital harbor in a geopolitically vulnerable area. The Hambantota port is a critical component of China's "string of pearls" plan, which aims to build a network of infrastructure across the Indian Ocean to promote commerce, increase China's geopolitical power in the area, and thus global influence. On the contrary, according to supporters of China's lending policies, the Hambantota port was merely an instance of a poorly planned enterprise that failed to draw the type of business it required to be fiscally viable, portraying China as an ‘ethical’ investor, simply looking to make long-term profits. They make the argument that Sri Lanka's debt issues are not exclusively a product of Chinese lending by pointing out how the country has borrowed money from some other foreign lenders in addition to China.

For instance, to fund its building projects, such as highways, ports, and power plants, the nation has drawn heavily from foreign creditors, including global institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and private creditors. The Sri Lankan rupee's decline against other major currencies, caused by the failure to raise significant profits from these initiatives, has made it increasingly difficult for the nation to meet its debt commitments. Poor fiscal management and administration problems have also worsened Sri Lanka's debt struggles. The nation's finances have been further strained by ineffective changes in revenue maximization strategies across major producers of the region and weak tax collection methods. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has also made the Sri Lankan financial problem more severe, as we mentioned in the previous paragraph.

In order to handle the Sri Lankan debt crisis, the government has taken some steps, including approaching foreign financial organizations like the IMF for help with debt restructuring. Unfortunately, the Sri Lankan people's living standards have been further affected by these measures' strict requirements, which include austerity measures, a cut in benefits coming from fiscal spending, and general systemic changes. And China remains a significant investor in Sri Lanka despite the disagreements regarding the Hambantota port project, thereby rendering investments in sectors like infrastructure, energy, and tourism. The government of Sri Lanka has made an effort to find a compromise between luring Chinese investment and steering away from the kinds of debt burdens that have been affecting other nations within the region or simply under the Chinese investment.

Future Implications

Sri Lanka is currently facing its worst recession since 1948. This is compounded by a crisis of faith in the government, naturally the cause of popular uprisings. Sri Lanka, as it turns to the IMF, becomes the first APAC country to default on its international debt in 23 years. In response to the situation, the Chinese Foreign Ministry maintains its position that its investment in Sri Lanka came with no additional political conditions and that the investment plan was scientifically planned. It has announced the intention of the Chinese state to engage with global financial institutions to “help Sri Lanka overcome its current challenges by easing its debt burden and achieving sustainable growth.” Simultaneously, however, it has blocked Sri Lanka’s access to a $1.5 billion swap line as well as a planned $2.5 billion credit facility. Therefore, it is not yet possible to ascertain the position of the Chinese state as Sri Lanka is subjected to an ample restructuring project. This case study does, however, invite an analysis of how the practice of international borrowing and lending is evolving outside of the Paris Club members as the global economy, as economists at Harvard, the World Bank, and the Kiel Institute describe, is essentially entering a new status quo, with China at the forefront of the developing world.

What does this mean for Sri Lanka?

A brief historical analysis of the IMF’s interventions reveals that they are seldom fruitful and sustainable. Sri Lanka stands to receive a $2.9bn IMF bailout, currently pending until after China and India agree to lower Sri Lanka’s debt. Even so, this bailout would barely be enough to cover the country’s annual fuel costs, while debt servicing would normally require $4-5bn. What may be consequential, however, is the IMF’s ability to restore confidence in Sri Lanka as a debtor. Furthermore, there are several parts of the economic plan it has outlined that address some of the things that have been the most problematic within Sri Lanka’s economic structure, including consistently high exchange rates and large proportions of nationalized enterprises. Apart from this, and independently from IMF presence, Sri Lanka needs to access bridge financing (enter very short-term debt agreements) specifically to consolidate its foreign reserves and secure access to staples (fuel and fertilizer). This would enable it to carry out normal economic activity once again and would have a stabilizing socio-political effect as well. Other considerations include deleveraging from international sovereign bond issuances and being more careful about the debt agreements the country enters in the future. Another cause for alarm, which arguably lies at the core of the current crisis, is the disproportionate reliance of the Sri Lankan economy on remittances. Supply-side policies which concern the development of internal industry and encouragement of competition could therefore be very consequential in allowing for greater structural sustainability within the economy in the long run, and a falling need to rely so heavily on debt. The development and execution of an industrial development plan would allow it to, in time, manage its “massive and protracted” trade deficit. Sri Lanka remains an important example of China’s multifaceted lending practices, and invites a deeper inquiry into the economic and political evolution of the APAC region, as China shows no signs of slowing down.

China and the World’s New Economic Order

The essence is in recognizing the fact that China’s lending and restructuring practices are diametrically opposite to those of Western countries; it generally does not waive debts, instead choosing to lengthen the loan term while leaving the principal amount unaffected. In Sri Lanka, China proposed new loans to pay off the old ones, a practice also called a rollover. This has been seen in many of the low-income countries that China almost exclusively lends to, such as Zambia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos, and Cambodia.

Sri Lanka is currently facing its worst recession since 1948. This is compounded by a crisis of faith in the government, naturally the cause of popular uprisings. Sri Lanka, as it turns to the IMF, becomes the first APAC country to default on its international debt in 23 years. In response to the situation, the Chinese Foreign Ministry maintains its position that its investment in Sri Lanka came with no additional political conditions and that the investment plan was scientifically planned. It has announced the intention of the Chinese state to engage with global financial institutions to “help Sri Lanka overcome its current challenges by easing its debt burden and achieving sustainable growth.” Simultaneously, however, it has blocked Sri Lanka’s access to a $1.5 billion swap line as well as a planned $2.5 billion credit facility. Therefore, it is not yet possible to ascertain the position of the Chinese state as Sri Lanka is subjected to an ample restructuring project. This case study does, however, invite an analysis of how the practice of international borrowing and lending is evolving outside of the Paris Club members as the global economy, as economists at Harvard, the World Bank, and the Kiel Institute describe, is essentially entering a new status quo, with China at the forefront of the developing world.

What does this mean for Sri Lanka?

A brief historical analysis of the IMF’s interventions reveals that they are seldom fruitful and sustainable. Sri Lanka stands to receive a $2.9bn IMF bailout, currently pending until after China and India agree to lower Sri Lanka’s debt. Even so, this bailout would barely be enough to cover the country’s annual fuel costs, while debt servicing would normally require $4-5bn. What may be consequential, however, is the IMF’s ability to restore confidence in Sri Lanka as a debtor. Furthermore, there are several parts of the economic plan it has outlined that address some of the things that have been the most problematic within Sri Lanka’s economic structure, including consistently high exchange rates and large proportions of nationalized enterprises. Apart from this, and independently from IMF presence, Sri Lanka needs to access bridge financing (enter very short-term debt agreements) specifically to consolidate its foreign reserves and secure access to staples (fuel and fertilizer). This would enable it to carry out normal economic activity once again and would have a stabilizing socio-political effect as well. Other considerations include deleveraging from international sovereign bond issuances and being more careful about the debt agreements the country enters in the future. Another cause for alarm, which arguably lies at the core of the current crisis, is the disproportionate reliance of the Sri Lankan economy on remittances. Supply-side policies which concern the development of internal industry and encouragement of competition could therefore be very consequential in allowing for greater structural sustainability within the economy in the long run, and a falling need to rely so heavily on debt. The development and execution of an industrial development plan would allow it to, in time, manage its “massive and protracted” trade deficit. Sri Lanka remains an important example of China’s multifaceted lending practices, and invites a deeper inquiry into the economic and political evolution of the APAC region, as China shows no signs of slowing down.

China and the World’s New Economic Order

The essence is in recognizing the fact that China’s lending and restructuring practices are diametrically opposite to those of Western countries; it generally does not waive debts, instead choosing to lengthen the loan term while leaving the principal amount unaffected. In Sri Lanka, China proposed new loans to pay off the old ones, a practice also called a rollover. This has been seen in many of the low-income countries that China almost exclusively lends to, such as Zambia, Ethiopia, Kenya, Laos, and Cambodia.

Whether this constitutes a debt trap is debatable - and a politically-charged issue. China’s Belt and Road Initiative is often harshly criticized by Western political institutions and denounced as being inherently predatory. The truth is, China remains one of the few financing options for many developing countries. Sri Lanka went to the USA and India for funding before it ever got involved with China, and was promptly turned away. As China seeks to further refine its position and affirm itself internationally, a game that it has not been playing for as long as it may seem, it is “developing [its investment] strategies, getting better at discerning business opportunities and withdrawing where [it] knows [it] can’t win”, as argued by a piece published in the Atlantic. There is also the role played by the interest rate hikes pursued by the US federal bank, which the Chinese government credits for aggravating the debt situations of developing countries. A broader look at China’s investment history in Sri Lanka reveals that BRI has enabled Sri Lanka to bridge its infrastructure gap in certain sectors (transport, coal, water, etc.), while there have also been some projects that were not economically viable. Perhaps the situation is more aptly characterized as an “asymmetric and imbalanced” relationship, rather than an overt trap.

Following a larger trend of multiple defaults on debt to China, China has expanded its emergency rescue lending, so much so that it now accounts for 60% of its overseas lending portfolio. This includes the global swap line network overseen by PBOC, which in 2022 provided $170bn in relief. These rescue loans are becoming more and more popular in general, and they come with a much higher interest rate - 5%, than the 2% rescue loan rate established by the IMF, as they are apparently easier to access.

Following a larger trend of multiple defaults on debt to China, China has expanded its emergency rescue lending, so much so that it now accounts for 60% of its overseas lending portfolio. This includes the global swap line network overseen by PBOC, which in 2022 provided $170bn in relief. These rescue loans are becoming more and more popular in general, and they come with a much higher interest rate - 5%, than the 2% rescue loan rate established by the IMF, as they are apparently easier to access.

In addition to this, their nature makes it so that there is a discrepancy between maturities de jure and de facto, which means that governments can opt not to recognize swap line borrowings from China as elements of public debt because international regulation states that only public debts with maturities exceeding one year need to be disclosed as public debts. According to the author of a study on this phenomenon, the growing prominence of China as an actor in this stage is consequential for the global financial and monetary system, which is becoming “multipolar, less institutionalized, and less transparent”. Simultaneously, China is developing its own system of global crisis management, and there is great overlap with the position that the US assumed following World War II, as it provided rescue funds to countries that were greatly indebted to US entities, which allowed it to place itself at the center of the global economy. As for the response from other economic powers, the debate has remained largely formal and political, with condemnations from actors such as the US and symmetrical reactions from China.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as China becomes increasingly more involved in the economies of low and middle-income countries, Sri Lanka’s case gains more ample relevance. Studying the factors that have led to the current situation reveals that the issue is a complex one: on one hand, these countries need sources of financing for their growth, while, on the other, they often encounter issues in foreign debt repayment. Considering all the nuances of the issue, it becomes apparent that we cannot definitively affirm that there is such thing as a debt trap, but, moving forward, countries should be highly cautious regarding the debt agreements they enter with China, and realistic about their ability to fulfill them.

In conclusion, as China becomes increasingly more involved in the economies of low and middle-income countries, Sri Lanka’s case gains more ample relevance. Studying the factors that have led to the current situation reveals that the issue is a complex one: on one hand, these countries need sources of financing for their growth, while, on the other, they often encounter issues in foreign debt repayment. Considering all the nuances of the issue, it becomes apparent that we cannot definitively affirm that there is such thing as a debt trap, but, moving forward, countries should be highly cautious regarding the debt agreements they enter with China, and realistic about their ability to fulfill them.

Written by Anastasia Larionova, Georgia-Alesia Mirica, Matilde Oliana, Mihaly Schieszler

Sources

- AID Data

- The Atlantic

- BBC

- The Diplomat

- ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute

- KDI School of Public Policy & Management

- Reuters

- UNDP Regional Bureau for APAC