While the majority of the continents of the world are still counting the victims of the pandemic and abruptly return to severe lockdowns that resemble the March’s situation, one big exception is experiencing months of normality: China. There, the nightmare of the illness seems behind at this point and the economy will avoid the sharp contraction that many countries of the world will face. One of the key factors that allowed this economic resilience has been the strength of its property market, but now, the government, is worried that all this cheap money will add debt to an already highly-leveraged industry, jeopardizing its financial stability.

Dynamic of urban growth in China

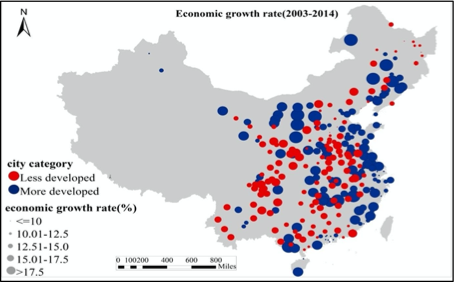

In the past decades, China has witnessed the biggest urban transformation in history: in 2018 eight Chinese cities were among the 50 largest metropolises of the world, and among the 561 agglomeration of more than 1 million people in the world, 114 were in China.

Between 1990 and 2014 China’s economy has grown on average 9.82 per cent per annum and much of this development has been due to the rapid growth of Chinese cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. This growth can be explained by some important elements: the location and accessibility of Chinese cities, which are usually close to the coast and have better transportation infrastructures; and the role of education and innovation, since Chinese cities attract university students and workers because they offer the best opportunities for personal progress and knowledge circulation; government efficiency and its fight against corruption at city levels.

Dynamic of urban growth in China

In the past decades, China has witnessed the biggest urban transformation in history: in 2018 eight Chinese cities were among the 50 largest metropolises of the world, and among the 561 agglomeration of more than 1 million people in the world, 114 were in China.

Between 1990 and 2014 China’s economy has grown on average 9.82 per cent per annum and much of this development has been due to the rapid growth of Chinese cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. This growth can be explained by some important elements: the location and accessibility of Chinese cities, which are usually close to the coast and have better transportation infrastructures; and the role of education and innovation, since Chinese cities attract university students and workers because they offer the best opportunities for personal progress and knowledge circulation; government efficiency and its fight against corruption at city levels.

Source: elaboration using China City Statistical Yearbook data.

Housing Market

A shrinkage in the number of Chinese people in working age starting from 2014 worried that the Chinese housing boom that dragged an impressive economic grew from 1990s could slow its trajectory. The fall of the country’s birth rate grows concerns about the long-term health of the property sector, which is estimated to comprise up to 25 per cent of China’s GDP. Then the pandemic hit, and the weak property construction data comes with no surprise as China has been in lockdown from January to April: in February housing sales fell almost 40 per cent and plunged in March too. Land space under construction between January and February rose by 2.9 per cent year on year, less than half the 6.8 per cent increase in the same period of 2019. Investments in the property market fell by 16.3 per cent between January and February. In the same period, China's property developers obtained 10.92 million m2 of new land leases, down 29.3 per cent from the year before. The overall valuation of these new leases amounted to Rmb44bn, down 36.2 per cent year over year. Investment in infrastructure construction declined by 30.3 per cent year over year in the first two months, compared with a 4.3 per cent rise in the same period last year.

Consumers were not able to leave their homes, and this meant that China’s property developers faced a tragic situation; over 100 builders went bust in the first two months of the year. Many of them, among which there is Evergrande, the Chinese biggest property developer, were forced to cut prices up to 25 percent in order to maintain cash flows.

House prices

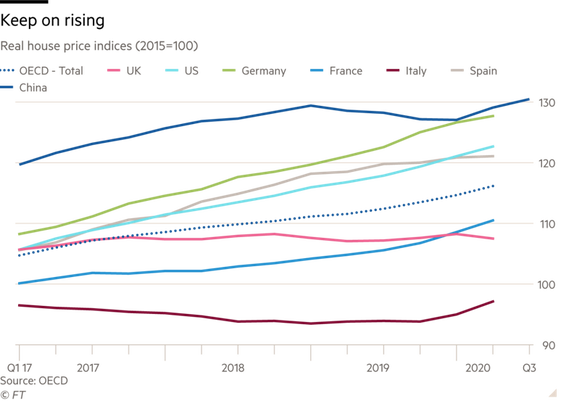

The pandemic has not just caused extraordinary changes in our social and working environments, but also the normal economic indicators seems no more reliable. Not only the stock market appears to many untied to the real economy, but the prices of the houses too are marking unexpected trajectories. Usually the housing market tends to fall as an economic downturn approaches and declining prices anticipate a recession, but this year, although the global recession, the property prices rose in many countries. In the world, it is clear that the economic downturn is still hitting, general wealth is down and rent prices are slowing, so the alternative to buying a house is getting more attractive: all things that wouldn’t explain rising house prices.

In China the situation is not different: house sales fell by almost 40 per cent in February, while average house prices in 70 Chinese cities rose by 5.8 per cent, compared with a 6.3 per cent increase in January.

The expansion and accumulation of wealth in the middle class and the urbanization politics promoted by the government lead to a boom of the market and the house prices in the 70 biggest Chinese cities rose in July 4.8 per cent year over year. But there is a city which is posting even more impressive numbers; as the leading technological city of China, Shenzen, has benefited from the shortage of lands and valuations of second-hand residential buildings have risen 78 per cent since the beginning of 2015, while the prices on new home are up 56 per cent; in July house prices added a 5.9 per cent year over year in Shenzen.

A shrinkage in the number of Chinese people in working age starting from 2014 worried that the Chinese housing boom that dragged an impressive economic grew from 1990s could slow its trajectory. The fall of the country’s birth rate grows concerns about the long-term health of the property sector, which is estimated to comprise up to 25 per cent of China’s GDP. Then the pandemic hit, and the weak property construction data comes with no surprise as China has been in lockdown from January to April: in February housing sales fell almost 40 per cent and plunged in March too. Land space under construction between January and February rose by 2.9 per cent year on year, less than half the 6.8 per cent increase in the same period of 2019. Investments in the property market fell by 16.3 per cent between January and February. In the same period, China's property developers obtained 10.92 million m2 of new land leases, down 29.3 per cent from the year before. The overall valuation of these new leases amounted to Rmb44bn, down 36.2 per cent year over year. Investment in infrastructure construction declined by 30.3 per cent year over year in the first two months, compared with a 4.3 per cent rise in the same period last year.

Consumers were not able to leave their homes, and this meant that China’s property developers faced a tragic situation; over 100 builders went bust in the first two months of the year. Many of them, among which there is Evergrande, the Chinese biggest property developer, were forced to cut prices up to 25 percent in order to maintain cash flows.

House prices

The pandemic has not just caused extraordinary changes in our social and working environments, but also the normal economic indicators seems no more reliable. Not only the stock market appears to many untied to the real economy, but the prices of the houses too are marking unexpected trajectories. Usually the housing market tends to fall as an economic downturn approaches and declining prices anticipate a recession, but this year, although the global recession, the property prices rose in many countries. In the world, it is clear that the economic downturn is still hitting, general wealth is down and rent prices are slowing, so the alternative to buying a house is getting more attractive: all things that wouldn’t explain rising house prices.

In China the situation is not different: house sales fell by almost 40 per cent in February, while average house prices in 70 Chinese cities rose by 5.8 per cent, compared with a 6.3 per cent increase in January.

The expansion and accumulation of wealth in the middle class and the urbanization politics promoted by the government lead to a boom of the market and the house prices in the 70 biggest Chinese cities rose in July 4.8 per cent year over year. But there is a city which is posting even more impressive numbers; as the leading technological city of China, Shenzen, has benefited from the shortage of lands and valuations of second-hand residential buildings have risen 78 per cent since the beginning of 2015, while the prices on new home are up 56 per cent; in July house prices added a 5.9 per cent year over year in Shenzen.

House prices in China, after a slowdown during all 2019, posted a major uptick from the beginning of 2020, and so did many of the major economies of the world.

The rise in the house prices can be explained looking at the huge stimulus that government and central banks have put in place, allowing workers to maintain their salary and keeping the cost of money very low.

Threat of China developers’ default

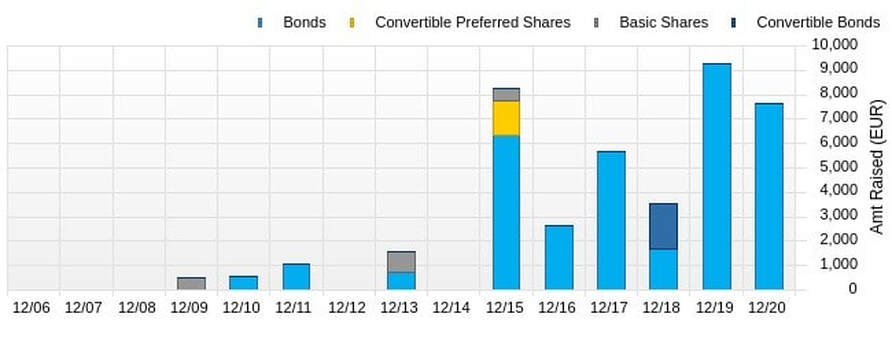

In the urbanization process that took place in China in those decades, property developers covered a fundamental role. But it is known that construction is an extremely capital-intensive industry, where borrowing is a key factor to access the credit to buy lands and stat constructing. Evergrande, which has enough land to house the entire Portugal’s population, has accumulated during the years more debt than New Zealand and now, with its $120bn of debt, has become the world’s most indebted property developer. China’s government is putting pressure on these highly-leveraged real estate companies to reduce their borrowing, anxious about the risks on their financial health and the possible consequences on the Chinese’s economic recovery.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the property developers have accumulated such a huge amount of debt through the China’s state-owned banks that funded a non-stop rush to buy and develop land, and through an increasingly important offshore bond market: today the majority of the Asia high-yield bonds are issued by Chinese developers. Evergrande is subject to risks that are similar to those faced by large banks: that its access to financing will end, leaving it with illiquid assets and causing a default that could transmit through the financial system. If we then add the fact that unlikely house prices will grow at this pace, even the collateral to their borrowing could lose value. A deleveraging mechanism has already taken place in China and government will keep a very close look to dangerous companies.

Threat of China developers’ default

In the urbanization process that took place in China in those decades, property developers covered a fundamental role. But it is known that construction is an extremely capital-intensive industry, where borrowing is a key factor to access the credit to buy lands and stat constructing. Evergrande, which has enough land to house the entire Portugal’s population, has accumulated during the years more debt than New Zealand and now, with its $120bn of debt, has become the world’s most indebted property developer. China’s government is putting pressure on these highly-leveraged real estate companies to reduce their borrowing, anxious about the risks on their financial health and the possible consequences on the Chinese’s economic recovery.

After the 2008 financial crisis, the property developers have accumulated such a huge amount of debt through the China’s state-owned banks that funded a non-stop rush to buy and develop land, and through an increasingly important offshore bond market: today the majority of the Asia high-yield bonds are issued by Chinese developers. Evergrande is subject to risks that are similar to those faced by large banks: that its access to financing will end, leaving it with illiquid assets and causing a default that could transmit through the financial system. If we then add the fact that unlikely house prices will grow at this pace, even the collateral to their borrowing could lose value. A deleveraging mechanism has already taken place in China and government will keep a very close look to dangerous companies.

Source of Capital of China Evergrande Group from 2006 to 2020

Source: Factset

Source: Factset

Many still think that a company like Evergrande is too big to fall: the urbanization rate in China will continue and support the sector, but it is reasonable to think that sooner or later will slow down and assume a normal shape. Moreover, an easing monetary policy should be a temporary measure, and when central banks’ support will finish, borrowing costs will return to normal values and piles of debt could start gaining weight on the Chinese developers’ balances.

Edoardo Zanetta

Edoardo Zanetta