Introduction

Tax systems, which are the combination of tax administration and tax policy, play a crucial role for fiscal policy and management of the public sector. Little tax revenue makes it difficult for governments to spend on public infrastructure, education and health services; on the other hand, high tax burdens also deter economic growth, as they discourage work effort and private investment.

In Asia, the practice of tax policy is peculiar when compared to other regions of the world. For instance, there is a difference in the composition of taxes; in fact, indirect taxes (value-added tax (VAT), sales tax, foreign trade, etc.) exceed direct taxes (corporate income tax, personal income tax, social security taxes, etc.) by 10%, whereas in the world average direct taxes exceed indirect taxes by 50%. Another difference is the role played by VAT. In terms of government revenues from indirect taxes, VAT amounts to a smaller share in Asia than in other parts of the world, since there generally are low VAT rates.

The tax systems of Asian countries such as China and South Korea, however, have undergone major changes in the last decades.

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949, reforms were introduced with the aim to modernise the country's governance system and administration capabilities.

China has sustained an average pre-pandemic growth rate of 10% annually for nearly two decades. The key ingredient fuelling this expansion is tax reduction, which has allowed a flow of funds into the private sector, causing the ratio of investment to consumption to steadily rise.

In the 1970s, the leader Deng Xiaoping began the Chinese Economic Reform. He established the first Special Economic Zones in the province of Shenzhen, allowing farmers to sell their crops at a free-market price and gradually crystallising “mini” market economies across China. Additionally, in 1978, he launched a reform package that significantly reduced the tax burden from 31% of the GDP to 10.7% at the end of 1995. Tax cuts and the shift towards a free market fuelled the privatisation of the economy, and thus economic growth. Slowly incorporating capitalist principles into its socialist philosophy, China moved from 2.9% yearly growth (1950-1973) to 9.5% between 1978 and 2013.

The largest tax reform was implemented in 1994, with the following key objectives: adopting the VAT as the core of the turnover tax system, reforming the enterprise income tax with the integration of pre-existing taxes into the enterprise income tax, and merging individual income taxes. The expansion of the VAT to the sale of goods, processing, and repair services reduced tax payments at the expenses of local governments, while directing more revenue to the central government.

The Business Tax to VAT Reform was implemented in 2016 and it covered all goods and services. The Value-added tax, thus, became China’s only indirect tax, replacing the Business Tax that previously applied to several industries. Thanks to this reform, service industries enjoy lower tax burdens, as they are only taxed on the value added at each transaction.

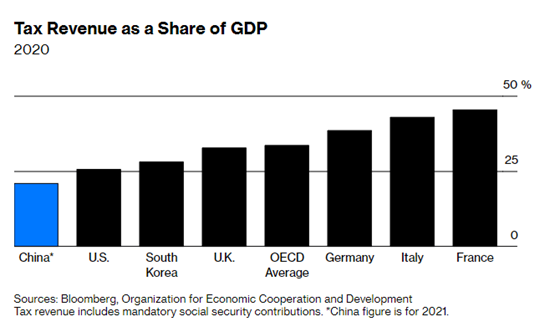

Shifting the focus to the Republic of South Korea, the reforms in its tax system have coincided with the capitalist development of the country. Over the past decades, as opposed to China, the tax revenue as a fraction of GDP has risen, but it is still low compared to the other countries in the OECD. The development of Korean tax policies has been highly growth-oriented, pursuing specific objectives, such as the promotion of savings, investments and R&D, as well as ensuring sufficient government revenues.

After the Japanese domination of the country in the 19th century, South Korea’s embryonic tax system was far from modern. In 1948, when the fort government of the country was formed, a proper tax system was introduced. During the 1960s, the objective of tax reforms was to make the tax system more supportive of economic development programs; thus, the government undertook them along with the Five-Year Economic Development Plans to promote rapid economic growth. In 1977, the VAT was introduced to replace eight of the eleven existing indirect taxes. In the 1980s, tax incentives were reduced and the focus shifted to the issue of the fair distribution of income and tax burden among different social groups.

Today’s Korean tax system is highly complex, with taxes being collected both at the local and national level. National taxes consist of three groups: internal taxes, three officially earmarked taxes, and customs duties. Personal and corporate income taxes and the VAT account for most of the national taxes. Property-related taxes account for more than half of local tax revenues.

China’s tax reforms

In what would seem like a rather peculiar embrace of neoclassical economic theory to an inattentive observer, China has been adventuring into ambitious tax reforms for over 5 years.

Yet President Xi Jinping, at the helm since 2012, exhibits some similarities to Deng Xiaoping from an economic perspective. While he is increasing the state’s grip on the economy through his support of state owned enterprises, he has also been encouraging the private sector, has relaxed lending standards and has increased foreign investor access to state’s bond markets. In the second volume of his book “The Governance of China'', President Xi inserted an entire section on “supply-side reform” which, he insists, is not pure, neoliberal “supply-side economics”, but a socialist interpretation. Xi’s writings and speeches also illustrate a focus on high-end tech.

In February, Chinese Finance Minister Liu Kun announced the country’s current tax benefits will expand through 2022, with a clear focus on facilities for the high-end tech industry, but also small businesses and pension benefits. In an extraordinary demonstration of the administration’s focus on efficiency, Minister Liu also noted that a higher degree of responsibility for public spending will go toward local administration, rather than the central government- also a trademark of neoclassical economic thinking.

This March, the Xi administration announced the equivalent of approximately $393 billion in tax reductions, entering a fifth consecutive year of such cuts totalling over $1.5 trillion- more than US President Donald Trump intended during his presidency. While the pandemic may have accelerated the country’s plans, with cuts in the reserve ratio and lower taxes just ahead of the Lunar Year shopping season in 2021, the economic philosophy currently on parade at the State Taxation Administration of the PRC is not isolated. Rather, it reflects a kind of thinking that has been dominating the Xi administration, who seem to sometimes favour Friedman and Hayek over Mao and Marx, at least in economic matters.

The current tax reforms are geared toward the high earners, with a two-part rationale. Firstly, higher earners are expected to spend more and help the country recover from the pandemic. Secondly, as China is looking to help consolidate high-tech industries, its support measures apply not only to the companies themselves, but also to their highly talented workers, who – the government hopes- will be incentivised to continue working in the country with lower personal income taxes.

China has a progressive tax system, with eighteen different types of taxes grouped into 3 categories: Goods and services; Income; Property and behaviour (including LAT, RET, farm taxes, tobacco tax, etc.). It has tax rates between 3 and 45%. In 2018, the National People’s Congress approved a law project to overhaul the tax system, marking the seventh review since 1980.

The country’s decisions appear to be scientifically backed. In a paper published in the China Economic Review (Lin and Jia, 2019), it is shown that the country’s Laffer curve vertex corresponds to a rate of approximately 40%, and tax cuts are recommended, with a final direct tax rate of approximately 35%.

However, as Xi’s hand reaches deeper and deeper into the government’s pockets, concerns for debt sustainability are starting to arise. Taxes as a percentage of the GDP are decreasing rapidly. National expenditures on scientific development rose over 7% In 2021. The real estate sector, which has contributed significantly to local government revenue (20% on average and as high as 40% in some regions, in 2019), has seen a meltdown caused by the central administration’s actions against overly indebted developers.

Tax systems, which are the combination of tax administration and tax policy, play a crucial role for fiscal policy and management of the public sector. Little tax revenue makes it difficult for governments to spend on public infrastructure, education and health services; on the other hand, high tax burdens also deter economic growth, as they discourage work effort and private investment.

In Asia, the practice of tax policy is peculiar when compared to other regions of the world. For instance, there is a difference in the composition of taxes; in fact, indirect taxes (value-added tax (VAT), sales tax, foreign trade, etc.) exceed direct taxes (corporate income tax, personal income tax, social security taxes, etc.) by 10%, whereas in the world average direct taxes exceed indirect taxes by 50%. Another difference is the role played by VAT. In terms of government revenues from indirect taxes, VAT amounts to a smaller share in Asia than in other parts of the world, since there generally are low VAT rates.

The tax systems of Asian countries such as China and South Korea, however, have undergone major changes in the last decades.

After the establishment of the PRC in 1949, reforms were introduced with the aim to modernise the country's governance system and administration capabilities.

China has sustained an average pre-pandemic growth rate of 10% annually for nearly two decades. The key ingredient fuelling this expansion is tax reduction, which has allowed a flow of funds into the private sector, causing the ratio of investment to consumption to steadily rise.

In the 1970s, the leader Deng Xiaoping began the Chinese Economic Reform. He established the first Special Economic Zones in the province of Shenzhen, allowing farmers to sell their crops at a free-market price and gradually crystallising “mini” market economies across China. Additionally, in 1978, he launched a reform package that significantly reduced the tax burden from 31% of the GDP to 10.7% at the end of 1995. Tax cuts and the shift towards a free market fuelled the privatisation of the economy, and thus economic growth. Slowly incorporating capitalist principles into its socialist philosophy, China moved from 2.9% yearly growth (1950-1973) to 9.5% between 1978 and 2013.

The largest tax reform was implemented in 1994, with the following key objectives: adopting the VAT as the core of the turnover tax system, reforming the enterprise income tax with the integration of pre-existing taxes into the enterprise income tax, and merging individual income taxes. The expansion of the VAT to the sale of goods, processing, and repair services reduced tax payments at the expenses of local governments, while directing more revenue to the central government.

The Business Tax to VAT Reform was implemented in 2016 and it covered all goods and services. The Value-added tax, thus, became China’s only indirect tax, replacing the Business Tax that previously applied to several industries. Thanks to this reform, service industries enjoy lower tax burdens, as they are only taxed on the value added at each transaction.

Shifting the focus to the Republic of South Korea, the reforms in its tax system have coincided with the capitalist development of the country. Over the past decades, as opposed to China, the tax revenue as a fraction of GDP has risen, but it is still low compared to the other countries in the OECD. The development of Korean tax policies has been highly growth-oriented, pursuing specific objectives, such as the promotion of savings, investments and R&D, as well as ensuring sufficient government revenues.

After the Japanese domination of the country in the 19th century, South Korea’s embryonic tax system was far from modern. In 1948, when the fort government of the country was formed, a proper tax system was introduced. During the 1960s, the objective of tax reforms was to make the tax system more supportive of economic development programs; thus, the government undertook them along with the Five-Year Economic Development Plans to promote rapid economic growth. In 1977, the VAT was introduced to replace eight of the eleven existing indirect taxes. In the 1980s, tax incentives were reduced and the focus shifted to the issue of the fair distribution of income and tax burden among different social groups.

Today’s Korean tax system is highly complex, with taxes being collected both at the local and national level. National taxes consist of three groups: internal taxes, three officially earmarked taxes, and customs duties. Personal and corporate income taxes and the VAT account for most of the national taxes. Property-related taxes account for more than half of local tax revenues.

China’s tax reforms

In what would seem like a rather peculiar embrace of neoclassical economic theory to an inattentive observer, China has been adventuring into ambitious tax reforms for over 5 years.

Yet President Xi Jinping, at the helm since 2012, exhibits some similarities to Deng Xiaoping from an economic perspective. While he is increasing the state’s grip on the economy through his support of state owned enterprises, he has also been encouraging the private sector, has relaxed lending standards and has increased foreign investor access to state’s bond markets. In the second volume of his book “The Governance of China'', President Xi inserted an entire section on “supply-side reform” which, he insists, is not pure, neoliberal “supply-side economics”, but a socialist interpretation. Xi’s writings and speeches also illustrate a focus on high-end tech.

In February, Chinese Finance Minister Liu Kun announced the country’s current tax benefits will expand through 2022, with a clear focus on facilities for the high-end tech industry, but also small businesses and pension benefits. In an extraordinary demonstration of the administration’s focus on efficiency, Minister Liu also noted that a higher degree of responsibility for public spending will go toward local administration, rather than the central government- also a trademark of neoclassical economic thinking.

This March, the Xi administration announced the equivalent of approximately $393 billion in tax reductions, entering a fifth consecutive year of such cuts totalling over $1.5 trillion- more than US President Donald Trump intended during his presidency. While the pandemic may have accelerated the country’s plans, with cuts in the reserve ratio and lower taxes just ahead of the Lunar Year shopping season in 2021, the economic philosophy currently on parade at the State Taxation Administration of the PRC is not isolated. Rather, it reflects a kind of thinking that has been dominating the Xi administration, who seem to sometimes favour Friedman and Hayek over Mao and Marx, at least in economic matters.

The current tax reforms are geared toward the high earners, with a two-part rationale. Firstly, higher earners are expected to spend more and help the country recover from the pandemic. Secondly, as China is looking to help consolidate high-tech industries, its support measures apply not only to the companies themselves, but also to their highly talented workers, who – the government hopes- will be incentivised to continue working in the country with lower personal income taxes.

China has a progressive tax system, with eighteen different types of taxes grouped into 3 categories: Goods and services; Income; Property and behaviour (including LAT, RET, farm taxes, tobacco tax, etc.). It has tax rates between 3 and 45%. In 2018, the National People’s Congress approved a law project to overhaul the tax system, marking the seventh review since 1980.

The country’s decisions appear to be scientifically backed. In a paper published in the China Economic Review (Lin and Jia, 2019), it is shown that the country’s Laffer curve vertex corresponds to a rate of approximately 40%, and tax cuts are recommended, with a final direct tax rate of approximately 35%.

However, as Xi’s hand reaches deeper and deeper into the government’s pockets, concerns for debt sustainability are starting to arise. Taxes as a percentage of the GDP are decreasing rapidly. National expenditures on scientific development rose over 7% In 2021. The real estate sector, which has contributed significantly to local government revenue (20% on average and as high as 40% in some regions, in 2019), has seen a meltdown caused by the central administration’s actions against overly indebted developers.

There is a considerable body of research indicating that the structure and financing of tax cuts is essential for their efficiency. For example, a paper of the Brookings Institution (Gale and Samwick 2014) showed that tax cuts are more likely to hurt economic development if accompanied by deficits, and they are more likely to lead to higher growth if well-targeted, i.e. reallocating resources toward their highest-value economic use. The latter seems to be the argument behind the country’s strategy, as illustrated by the key sectors they target the cuts at.

In the context of slowing growth, economists are divided as to who should be the primary beneficiary of fiscal facilities: businesses or households. China’s current focus is on businesses, as the activity of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises accounts for 60% of the GDP and they have been especially affected by the pandemic. In major EU economies, the share of tax revenue as a percentage of GDP is much higher, as illustrated in the figure below.

As Premier Li, China’s foremost supply-side promoter, is stepping down this year, there is some uncertainty as to whether the excitement for tax breaks will continue.

In the context of slowing growth, economists are divided as to who should be the primary beneficiary of fiscal facilities: businesses or households. China’s current focus is on businesses, as the activity of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises accounts for 60% of the GDP and they have been especially affected by the pandemic. In major EU economies, the share of tax revenue as a percentage of GDP is much higher, as illustrated in the figure below.

As Premier Li, China’s foremost supply-side promoter, is stepping down this year, there is some uncertainty as to whether the excitement for tax breaks will continue.

Korea’s tax reforms

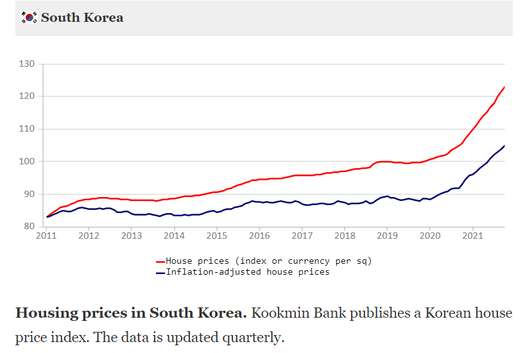

While China has used tax cuts to fuel economic growth, Korea has implemented them for something quite different. If there’s been one asset class that has highlighted South Korea’s asset pricing in the last decade, it would without a doubt be real estate. It is also the highlight of the recent election in Korea, where the conservative candidate Yoon Seok Youl beat out the incumbent party and candidate Lee Jae Myung by a thin 0.8% margin. South Korea’s real estate prices have seen double-digit growth throughout the pandemic, pricing many future homebuyers out of the market. According to Korea Times, the official house prices increased by 19.5% in 2021 and 5.98% in 2020, with expected double digits growth continuing into 2022: Koommin Bank estimated that house prices increased by 18.75% year on year. Housing prices are as much a financial topic as they are a political one, and were one of the main driving factors as to why Yoon Seok Youl was able to snag the victory. With apartment prices increasing by 50% under Moon Jae In’s term, South Korea has been struggling to keep prices under control, even with the implementation of policies like agency fee caps. Similar to what we’ve seen in other asian countries, Yoon’s administration promises to change the direction of real estate by introducing a reduction in taxes, particularly in property taxes.

While China has used tax cuts to fuel economic growth, Korea has implemented them for something quite different. If there’s been one asset class that has highlighted South Korea’s asset pricing in the last decade, it would without a doubt be real estate. It is also the highlight of the recent election in Korea, where the conservative candidate Yoon Seok Youl beat out the incumbent party and candidate Lee Jae Myung by a thin 0.8% margin. South Korea’s real estate prices have seen double-digit growth throughout the pandemic, pricing many future homebuyers out of the market. According to Korea Times, the official house prices increased by 19.5% in 2021 and 5.98% in 2020, with expected double digits growth continuing into 2022: Koommin Bank estimated that house prices increased by 18.75% year on year. Housing prices are as much a financial topic as they are a political one, and were one of the main driving factors as to why Yoon Seok Youl was able to snag the victory. With apartment prices increasing by 50% under Moon Jae In’s term, South Korea has been struggling to keep prices under control, even with the implementation of policies like agency fee caps. Similar to what we’ve seen in other asian countries, Yoon’s administration promises to change the direction of real estate by introducing a reduction in taxes, particularly in property taxes.

South Korea has had long standing issues with the property market. And with all time low interest rates and a nascent stock market, most of the speculative dry power in Korea is focused primarily on the housing market. This, coupled with the youth unemployment rate at 10% and a pandemic that decimated the disposable income, has left Korea in a perilous situation. The idea behind the new policy is to lower the burden that homeowners pass onto tenants, which could further exacerbate the pricing of homes in a positive feedback loop. Initially, there will be a property tax freeze on homes appraised over $905,000, followed by a new reduction to taxes for homeowners. Specifically, the administration is targeting new home buyers, where owners of multiple houses will receive tax relief if they sell their homes to first time buyers, redistributing home ownership. In addition, rising interest rates and an increase in promised housing supply has cooled down the real estate market temporarily, but uncertainty around eased rules on reconstruction and redevelopment has left the prices lingering.

Furthermore, Yoon’s administration has pledged to build an additional 2.5 million homes during his term, with 1.2 million additional units in Seoul, following up on the previous administration’s pledge of an additional 830,000 housing units nationwide and 325,000 specific additional units in Seoul. New single home buyers can buy the properties at below the market rate, and resell back to the government after 5 years, with up to a 70% return on investment margin. Yoon’s promises of lowering tax rates and increasing additional supplies aim to reduce speculative pricing on real estate assets, yet the government has said last year it plans to raise state evaluated prices for land and housing by up to 90% within the next 10-15 years, a stark contrast to what his government aimed to curb. In conclusion, current issues of real estate bubbles can be observed not just in South Korea but also across the globe, and whether Yoon’s promised tax cuts will have a sufficient impact, is something ultimately only time can tell.

Sources:

Asian Development Bank

Bank for International Settlements (BIS Papers)

BBVA Research

Bloomberg

Brookings Institution

Center for Strategic and International Studies

China Briefing

China Economic Review

China Macro Economy

CNBC

Council on Foreign Relations

Fitch Ratings

Global Property Guide

Harvard Library

National Bureau of Economic Research

OECD

PwC China

Reuters

State Taxation Administration of the People’s Republic of China

The Korea Times

The Tax Foundation

The World Bank

Yonhap News Agency

By Margherita Magenta, Teodor Matei and Tom Nguyen

Furthermore, Yoon’s administration has pledged to build an additional 2.5 million homes during his term, with 1.2 million additional units in Seoul, following up on the previous administration’s pledge of an additional 830,000 housing units nationwide and 325,000 specific additional units in Seoul. New single home buyers can buy the properties at below the market rate, and resell back to the government after 5 years, with up to a 70% return on investment margin. Yoon’s promises of lowering tax rates and increasing additional supplies aim to reduce speculative pricing on real estate assets, yet the government has said last year it plans to raise state evaluated prices for land and housing by up to 90% within the next 10-15 years, a stark contrast to what his government aimed to curb. In conclusion, current issues of real estate bubbles can be observed not just in South Korea but also across the globe, and whether Yoon’s promised tax cuts will have a sufficient impact, is something ultimately only time can tell.

Sources:

Asian Development Bank

Bank for International Settlements (BIS Papers)

BBVA Research

Bloomberg

Brookings Institution

Center for Strategic and International Studies

China Briefing

China Economic Review

China Macro Economy

CNBC

Council on Foreign Relations

Fitch Ratings

Global Property Guide

Harvard Library

National Bureau of Economic Research

OECD

PwC China

Reuters

State Taxation Administration of the People’s Republic of China

The Korea Times

The Tax Foundation

The World Bank

Yonhap News Agency

By Margherita Magenta, Teodor Matei and Tom Nguyen