Introduction

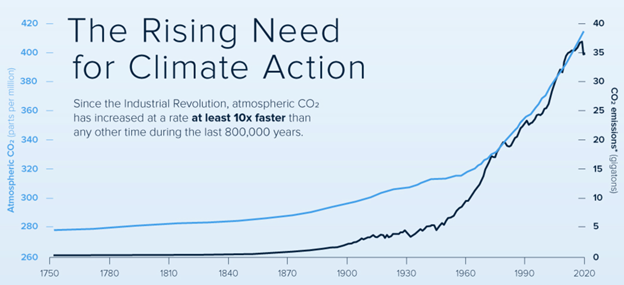

For two weeks earlier this month (October 31 - November 12), world leaders from nearly every country, negotiators, business leaders, and representatives of civil society groups gathered in Glasgow for the 26th annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). The importance of the COP conference can not be understated as atmospheric CO2 levels are increasing faster than at any other time in the last 800,000 years. In fact, many believe climate change issues are one of the most pressing issues of our time.

For two weeks earlier this month (October 31 - November 12), world leaders from nearly every country, negotiators, business leaders, and representatives of civil society groups gathered in Glasgow for the 26th annual United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26). The importance of the COP conference can not be understated as atmospheric CO2 levels are increasing faster than at any other time in the last 800,000 years. In fact, many believe climate change issues are one of the most pressing issues of our time.

Figure 1 - Increase in the level of atmospheric CO2 during the last years

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

Hoping to counter criticisms of earlier conferences concerning the efficacy and lack of serious dependence on scientific data, COP26 set lofty goals. Chiefly, it aimed to demonstrate a greater sense of urgency, legitimacy, and science-based approach to climate change. Thus, the conference is happy to report what it deems to be significant outcomes. Such outcomes include a collective decision to phase down unabated coal power, and more formal attention was given to topics such as emissions reductions, helping lower developed countries with these initiatives, and how to finance these commitments. However, the most significant outcome is the “Glasgow Climate Pact” – an agreement that extends an earlier pledge to limit global warming temperatures to 1.5°C per year. It should be noted that to achieve the 1.5°C per year benchmark, greenhouse gas emissions would need to be reduced by 50% from their current level by 2030. Thus, some question the conference’s seemingly optimistic conclusions and whether the global community will be able to follow-through.

Article 6 and the international carbon market

Nevertheless, quite possibly, the most interesting outcome of this year’s conference was “Article 6” – one of the most complex concepts of this year’s discussions. The article itself was actually introduced in 2015 on the last morning of the Paris negotiations, but it was left unresolved at the Katowice climate conference and placed on this year’s agenda. Prior to COP26, there was much speculation that framed Article 6 as a defining point for climate change talks; it would either assist the world avoid disastrous levels of global warming or enable some countries’ complacency in making meaningful emissions reductions. While perhaps slightly over exaggerated, it is fair to say that the Paris Agreement and the legitimacy of countries’ climate pledges were, to some degree, jeopardized.

Article 6 addresses the complexities of establishing an international carbon market.

The concept of an international carbon market emerged as an additional tool for helping countries in meeting their emissions reduction targets, which are described under their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The market is based on an emission trading scheme: countries can purchase emissions reductions from other countries that have reduced their emissions more than the target amount, for instance by switching to renewable energy. If the rules are properly structured, results can benefit every country involved.

Nevertheless, quite possibly, the most interesting outcome of this year’s conference was “Article 6” – one of the most complex concepts of this year’s discussions. The article itself was actually introduced in 2015 on the last morning of the Paris negotiations, but it was left unresolved at the Katowice climate conference and placed on this year’s agenda. Prior to COP26, there was much speculation that framed Article 6 as a defining point for climate change talks; it would either assist the world avoid disastrous levels of global warming or enable some countries’ complacency in making meaningful emissions reductions. While perhaps slightly over exaggerated, it is fair to say that the Paris Agreement and the legitimacy of countries’ climate pledges were, to some degree, jeopardized.

Article 6 addresses the complexities of establishing an international carbon market.

The concept of an international carbon market emerged as an additional tool for helping countries in meeting their emissions reduction targets, which are described under their nationally determined contributions (NDCs). The market is based on an emission trading scheme: countries can purchase emissions reductions from other countries that have reduced their emissions more than the target amount, for instance by switching to renewable energy. If the rules are properly structured, results can benefit every country involved.

The points of contention surrounding Article 6

The two largest points of contention surrounding Article 6 include the concepts of “double counting” and the risk of “fake credits”

“Double counting” can be attributed to the nascent and largely unregulated concept of a carbon market. It refers to when a country’s purchase of a carbon credit would be counted towards that country’s climate initiatives and towards the country where the emissions reduction actually occurred.

On the other hand, “fake credits” concern themselves with the authenticity of the progress being made. A credit is considered “fake” if an emission reduction is purchased for something that would have already occurred regardless of the purchase/investment – essentially, no additional climate change progress is made with the purchase of the credit.

Following COP26, there is bad news with regards to the issue of “fake credits” Parties agreed to a “carry-over” policy from the Kyoto Protocol dating back to 2013, which means that climate progress made prior to 2013 and the purchase of credits for this progress can be carried-over/counted towards today’s goals. Many found this particular outcome disappointing as it, arguably, did legitimize the idea of a “fake credit” by giving credence to climate progress that’s already been made. Furthermore, an additional disappointment was that allocating funds from the profits made from the trading of carbon credits towards the “adaptation” initiative remains “highly encouraged” and essentially voluntary. Some claim the lack of accountability here to be counterproductive because the “adaptation” goal of the conference specifically addresses climate change initiative financing issues where less developed countries are concerned.

However, the good news is that COP26 instituted a larger crackdown concerning “double counting” issues, and the committee seemed to possess a high-degree of self-awareness. The existing framework’s imperfections were inadvertently acknowledged by the conference’s commitment to the creation of a supervisory body beginning in 2022, further technical evaluation, and a set review for 2028 to re-evaluate limits on carbon credits themselves – as there are additional concerns surrounding the efficacy of the credits themselves (i.e., whether the effect of a purchased credit is truly comparable to emissions reductions in the country itself).

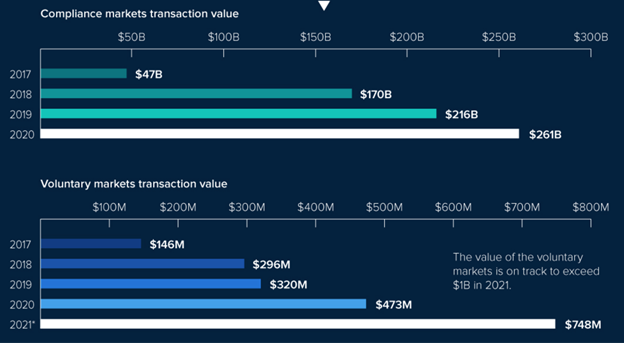

The popularity buzzing around international carbon markets has given way to more talks concerning similar markets for companies to partake in as well. While also relatively new, the compliance and voluntary based carbon markets for firms to engage in carbon credit offsetting in order to reach “net zero” goals are growing quickly and valued at $216 bn and $748 mn respectively. Thus, the U.S. industry implementation of carbon offsetting will also be discussed later in this article.

The two largest points of contention surrounding Article 6 include the concepts of “double counting” and the risk of “fake credits”

“Double counting” can be attributed to the nascent and largely unregulated concept of a carbon market. It refers to when a country’s purchase of a carbon credit would be counted towards that country’s climate initiatives and towards the country where the emissions reduction actually occurred.

On the other hand, “fake credits” concern themselves with the authenticity of the progress being made. A credit is considered “fake” if an emission reduction is purchased for something that would have already occurred regardless of the purchase/investment – essentially, no additional climate change progress is made with the purchase of the credit.

Following COP26, there is bad news with regards to the issue of “fake credits” Parties agreed to a “carry-over” policy from the Kyoto Protocol dating back to 2013, which means that climate progress made prior to 2013 and the purchase of credits for this progress can be carried-over/counted towards today’s goals. Many found this particular outcome disappointing as it, arguably, did legitimize the idea of a “fake credit” by giving credence to climate progress that’s already been made. Furthermore, an additional disappointment was that allocating funds from the profits made from the trading of carbon credits towards the “adaptation” initiative remains “highly encouraged” and essentially voluntary. Some claim the lack of accountability here to be counterproductive because the “adaptation” goal of the conference specifically addresses climate change initiative financing issues where less developed countries are concerned.

However, the good news is that COP26 instituted a larger crackdown concerning “double counting” issues, and the committee seemed to possess a high-degree of self-awareness. The existing framework’s imperfections were inadvertently acknowledged by the conference’s commitment to the creation of a supervisory body beginning in 2022, further technical evaluation, and a set review for 2028 to re-evaluate limits on carbon credits themselves – as there are additional concerns surrounding the efficacy of the credits themselves (i.e., whether the effect of a purchased credit is truly comparable to emissions reductions in the country itself).

The popularity buzzing around international carbon markets has given way to more talks concerning similar markets for companies to partake in as well. While also relatively new, the compliance and voluntary based carbon markets for firms to engage in carbon credit offsetting in order to reach “net zero” goals are growing quickly and valued at $216 bn and $748 mn respectively. Thus, the U.S. industry implementation of carbon offsetting will also be discussed later in this article.

Figure 2 - Compliance and voluntary markets transaction

Source: Visual Capitalist

Source: Visual Capitalist

USA in COP26

The United States of America, represented by their climate envoy John F. Kerry, showed their participation during the COP26 U.N. climate summit conference. They formally withdrew from the Climate Agreement a year ago since the former U.S. President Donald Trump argued that the agreement would benefit Paris rather than Pittsburgh. On the other hand, current president Bident from his first day of administration, decided to sign an executive order to rejoin. The participation of this country is crucial due to its political and financial power, as well as its responsibility for being the second contributing country after China to global greenhouse gas emissions, with 13% of total annual emissions.

During the meeting, the United States and European Union convinced more than 100 countries to support the deep cuts in emissions of methane, the potent greenhouse gas. Furthermore, the US agreed to join a coalition to fight deforestation, which is destroying the world’s carbon sinks. A big debate concerned the request from other countries for unequivocal commitment to end all fossil fuel subsidies by the American government that finally accepted to cut assistance to “unabated” coal and “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

The most difficult issue for the United States, as the richest country in the world, involves money payment. Twelve years ago, at a United Nations climate conference in Copenhagen, rich nations promised to channel US$100 bn a year to less wealthy nations by 2020, in order to help them adjust to climate change and diminish further rises in temperature. In 2020 The United States failed to send its part of the $100 billion payment wealthy countries had promised to deliver. Instead, in 2023, the wealthy countries will reach the $100 billion mark and it is expected they will make up for their initial loss by 2025.

Kerry and the top EU climate official, Frans Timmermans, collaborated with each other as they held one meeting after another to try to win an agreement, splitting up countries to leverage their influence. While the Americans had Brazil and Saudi Arabia, EU worked harder on African countries. According to one European negotiator, the return of the U.S in the coalition is fundamental since this nation has sway in parts of the world that Europe does not have. For instance, China, whose chief climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua has decided to explore an agreement with Kerry, is one of those places. No relationship is more essential than that between the United States and China, but it has been strained by disagreements over trade, as well as Beijing's treatment of Uyghur Muslims, which the Biden administration has labeled "genocide". Kerry and Xie had mainly virtual communication before the conference, however in Glasgow, Xie walked into a media briefing room before Kerry's speech. The two countries formed a joint working team, vowing "increasing climate action" to remain within the Paris Agreement's temperature constraints. Xie and Kerry further discussed during the penultimate day of the summit to work out an agreement.

The United States of America, represented by their climate envoy John F. Kerry, showed their participation during the COP26 U.N. climate summit conference. They formally withdrew from the Climate Agreement a year ago since the former U.S. President Donald Trump argued that the agreement would benefit Paris rather than Pittsburgh. On the other hand, current president Bident from his first day of administration, decided to sign an executive order to rejoin. The participation of this country is crucial due to its political and financial power, as well as its responsibility for being the second contributing country after China to global greenhouse gas emissions, with 13% of total annual emissions.

During the meeting, the United States and European Union convinced more than 100 countries to support the deep cuts in emissions of methane, the potent greenhouse gas. Furthermore, the US agreed to join a coalition to fight deforestation, which is destroying the world’s carbon sinks. A big debate concerned the request from other countries for unequivocal commitment to end all fossil fuel subsidies by the American government that finally accepted to cut assistance to “unabated” coal and “inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”.

The most difficult issue for the United States, as the richest country in the world, involves money payment. Twelve years ago, at a United Nations climate conference in Copenhagen, rich nations promised to channel US$100 bn a year to less wealthy nations by 2020, in order to help them adjust to climate change and diminish further rises in temperature. In 2020 The United States failed to send its part of the $100 billion payment wealthy countries had promised to deliver. Instead, in 2023, the wealthy countries will reach the $100 billion mark and it is expected they will make up for their initial loss by 2025.

Kerry and the top EU climate official, Frans Timmermans, collaborated with each other as they held one meeting after another to try to win an agreement, splitting up countries to leverage their influence. While the Americans had Brazil and Saudi Arabia, EU worked harder on African countries. According to one European negotiator, the return of the U.S in the coalition is fundamental since this nation has sway in parts of the world that Europe does not have. For instance, China, whose chief climate negotiator Xie Zhenhua has decided to explore an agreement with Kerry, is one of those places. No relationship is more essential than that between the United States and China, but it has been strained by disagreements over trade, as well as Beijing's treatment of Uyghur Muslims, which the Biden administration has labeled "genocide". Kerry and Xie had mainly virtual communication before the conference, however in Glasgow, Xie walked into a media briefing room before Kerry's speech. The two countries formed a joint working team, vowing "increasing climate action" to remain within the Paris Agreement's temperature constraints. Xie and Kerry further discussed during the penultimate day of the summit to work out an agreement.

Looking Ahead: Industry Implementations

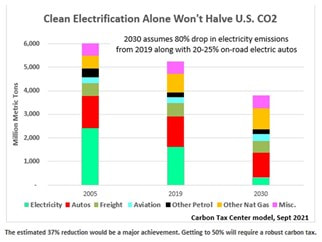

A significant industry discussed in the COP26 conference talks was the automotive industry and its transition towards decarbonization. Cars and trucks emit around one fifth of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, yet the United States was among some of the largest automotive markets absent from the pledges of transitioning to 100% zero-emission car and van sales by 2040 globally and by 2035 in leading markets. In addition, while Ford and General Motors signed on to the agreement at the conference, the top two automakers Toyota and Volkswagen refused to sign. However, it has become clear that without a robust carbon price in place, achieving Biden’s 50% by 2030 reduction in emissions goal appears unrealistic. The challenges faced by regulators, businesses and environmentalists in agreeing on a common time frame, pricing, measurement and transparency lie ahead.

A significant industry discussed in the COP26 conference talks was the automotive industry and its transition towards decarbonization. Cars and trucks emit around one fifth of U.S. greenhouse gas emissions, yet the United States was among some of the largest automotive markets absent from the pledges of transitioning to 100% zero-emission car and van sales by 2040 globally and by 2035 in leading markets. In addition, while Ford and General Motors signed on to the agreement at the conference, the top two automakers Toyota and Volkswagen refused to sign. However, it has become clear that without a robust carbon price in place, achieving Biden’s 50% by 2030 reduction in emissions goal appears unrealistic. The challenges faced by regulators, businesses and environmentalists in agreeing on a common time frame, pricing, measurement and transparency lie ahead.

Figure 3

Source: Utility Dive

Source: Utility Dive

The vision of a greener transport sector and increased electrification has been communicated by the Biden administration, with Biden announcing that half of new cars sold in the U.S. are to be battery-powered by 2030, in addition to a larger tax credit for electric vehicles. As momentum towards production of electric vehicles (EVs) picks up, global production is estimated to reach 23.6 mn units by 2030, 22.1% of the total light vehicle market. Similar to the EU, the U.S. has implemented fines for vehicle companies missing targets of weighted CO2 averages, incentivizing automotive companies to progress developments and sales of EVs and Hybridge. While China has seen faster advancements than other nations, with the share of EVs on the road has seen a drastic increase in 2020 to 48%, a greater proportion of the combined U.S. and Europe statistic.

While short-term federal carbon pricing remains unlikely, the state of California has proven that policies targeting appliances, building, transportation and fuel efficiency are contributing to reduced emissions. Currently, California is the only American state with a cap-and-trade market for carbon in place, which recently saw prices rise to a record high in the latest quarterly auction. The state’s aim of lowering emissions to 40% below 1990 levels involves around 450 entities targeting an overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 15%. Allowances to emit one metric ton of carbon dioxide this year sold for $28.26 in the auction, a hefty premium over the $17.71 offering price, as stated by California Air Resources Board. This reflects the increased demand from companies, striving to achieve net-zero programs, with the market expected to see further growth in the future. Carbon credits in the state are predicted to rise by 66% to $41by 2030 (International Emissions Trading Association).

Similarly, the agricultural sector is under pressure to act in decreasing carbon emissions in the near future. Whilst the U.S. Department of Agriculture has not put in place its own standards for carbon credits, carbon capturing projects and other initiatives have been developed thus far. Global cropland has the potential to eliminate up to 570 million metric tons of carbon per year. However, farm-based offsets are currently unregulated, thus enhanced rigorous standards must be implemented for carbon credits to display the desired effect.

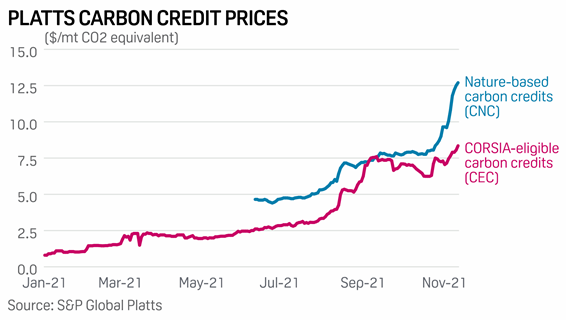

Furthermore, the airline industry accounted for an estimated 2.4 % of total carbon dioxide in 2018. Despite facing a drastic decline in demand as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry is predicted to resume strong growth, with passenger revenue experiencing 4.4% annual growth over the coming two decades. The civilian aviation sector was excluded from the Paris Climate Accord , yet since then there have been developments in carbon emissions reductions, through the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s introduction of the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) in 2016. Along with other carbon markets, CORSIA carbon credits saw record prices in the past month, in the run up to the COP-26 conference.

While short-term federal carbon pricing remains unlikely, the state of California has proven that policies targeting appliances, building, transportation and fuel efficiency are contributing to reduced emissions. Currently, California is the only American state with a cap-and-trade market for carbon in place, which recently saw prices rise to a record high in the latest quarterly auction. The state’s aim of lowering emissions to 40% below 1990 levels involves around 450 entities targeting an overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions of 15%. Allowances to emit one metric ton of carbon dioxide this year sold for $28.26 in the auction, a hefty premium over the $17.71 offering price, as stated by California Air Resources Board. This reflects the increased demand from companies, striving to achieve net-zero programs, with the market expected to see further growth in the future. Carbon credits in the state are predicted to rise by 66% to $41by 2030 (International Emissions Trading Association).

Similarly, the agricultural sector is under pressure to act in decreasing carbon emissions in the near future. Whilst the U.S. Department of Agriculture has not put in place its own standards for carbon credits, carbon capturing projects and other initiatives have been developed thus far. Global cropland has the potential to eliminate up to 570 million metric tons of carbon per year. However, farm-based offsets are currently unregulated, thus enhanced rigorous standards must be implemented for carbon credits to display the desired effect.

Furthermore, the airline industry accounted for an estimated 2.4 % of total carbon dioxide in 2018. Despite facing a drastic decline in demand as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, the industry is predicted to resume strong growth, with passenger revenue experiencing 4.4% annual growth over the coming two decades. The civilian aviation sector was excluded from the Paris Climate Accord , yet since then there have been developments in carbon emissions reductions, through the International Civil Aviation Organisation’s introduction of the Carbon Offsetting and Reduction Scheme for International Aviation (CORSIA) in 2016. Along with other carbon markets, CORSIA carbon credits saw record prices in the past month, in the run up to the COP-26 conference.

Figure 4 - Platts Carbon Credit Prices

Source: S&P Global Patts

Source: S&P Global Patts

Airlines are seeking to reduce their greenhouse gases footprint through developing sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) from grain, oilseed crops or agricultural waste, in order to minimize the use of petroleum fuels. For example, since 2016 United Airlines began to use jet fuel comprising 30% of biofuels for its flights from Los Angeles to San Francisco, along with Jet Blue for flights departing from New York City, initially consisting of 20% of renewables. Last month, United Airlines launched a test flight running on 100% SAF, and the airline is set to become the first commercial airline operating a 100% drop-in SAF flight. Similarly, before the COP-26 conference, multiple airlines announced their commitments to achieve 10% SAF use by 2030.

Conclusion

To summarize, Biden’s decision to rejoin the alliance has been a significant event and will contribute to making significant changes and contribution to climate change mitigation and fossil fuel reduction policies. However, according to some analysts, the newly established carbon market mechanism under the Paris Agreement might take up to three years to take shape.

To summarize, Biden’s decision to rejoin the alliance has been a significant event and will contribute to making significant changes and contribution to climate change mitigation and fossil fuel reduction policies. However, according to some analysts, the newly established carbon market mechanism under the Paris Agreement might take up to three years to take shape.

Sources

Guglielmo Lucio Palmieri, Ava Mei Trahan, Jasmin Esermann

- S&P Global Patts

- BBC News

- BNN Bloomberg

- Carbon Plus

- NPR

- Utility Dive

- NBC News

- AG Web

Guglielmo Lucio Palmieri, Ava Mei Trahan, Jasmin Esermann