Since the beginning of Covid-19 crisis, the value of the U.S. dollar — widely considered a safe-haven in times of financial distress — has been increasing steadily, reaching its strongest point ever in March, when stock and bond markets suffered the most critical phase of the virus impact. A month later, despite the massive flood of new dollars, the currency remains strong,

nearly 10% higher against the Australian dollar and 25 % stronger against the Mexican peso than at the beginning of the year.

The dollar is more than merely the ‘chief reserve currency’: it is considered a safe-haven currency, the one companies turn to in moments of crisis, a role it has played during other major economic crises as well. However, while in good times it is convenient to have large parts of the world transactions denominated in dollars, in crisis periods this over-reliance can be an issue.

In particular, there are three major drawbacks. The first issue is related to U.S. exports, which inevitably become more expensive, making it harder for Americans to sell their products abroad. Local companies are more tempted to open factories and facilities in foreign countries, where operations and labor are cheaper, which inevitably leads to an increase in the domestic unemployment level.

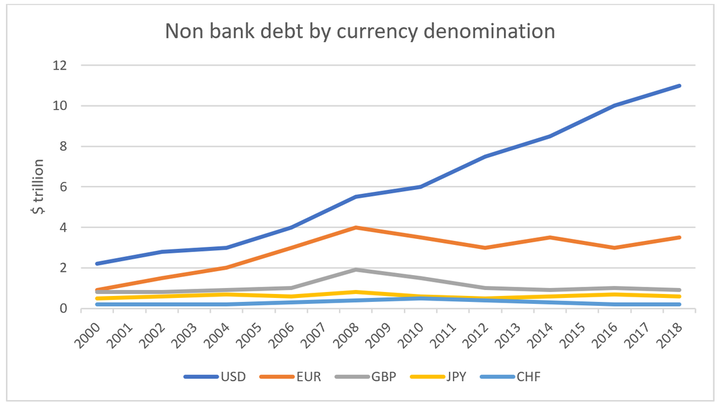

The second problem concerns the global demand for the dollar, not to mention US treasury bonds, which gives the United States real leverage. For any non-U.S. corporate with dollar-denominated debt to be swapped to local currencies, they now have to repay that much more in local currency equivalent, which is a significant addition to any dramatic drop in revenues as a result of the crisis. As a matter of fact, since the 2008 crisis, the dominance of the USD in international trade has increased dramatically, with its usage extending also to debt. This increase in dollar corporate debt is largely due to a heavier reliance on financial markets rather than banks: this market-based leverage is a consequence of Basel III rules, according to which banks needed to have stronger balance sheets to better handle shocks like the 2008 financial crisis, meaning the bank proportion of lending has declined.

nearly 10% higher against the Australian dollar and 25 % stronger against the Mexican peso than at the beginning of the year.

The dollar is more than merely the ‘chief reserve currency’: it is considered a safe-haven currency, the one companies turn to in moments of crisis, a role it has played during other major economic crises as well. However, while in good times it is convenient to have large parts of the world transactions denominated in dollars, in crisis periods this over-reliance can be an issue.

In particular, there are three major drawbacks. The first issue is related to U.S. exports, which inevitably become more expensive, making it harder for Americans to sell their products abroad. Local companies are more tempted to open factories and facilities in foreign countries, where operations and labor are cheaper, which inevitably leads to an increase in the domestic unemployment level.

The second problem concerns the global demand for the dollar, not to mention US treasury bonds, which gives the United States real leverage. For any non-U.S. corporate with dollar-denominated debt to be swapped to local currencies, they now have to repay that much more in local currency equivalent, which is a significant addition to any dramatic drop in revenues as a result of the crisis. As a matter of fact, since the 2008 crisis, the dominance of the USD in international trade has increased dramatically, with its usage extending also to debt. This increase in dollar corporate debt is largely due to a heavier reliance on financial markets rather than banks: this market-based leverage is a consequence of Basel III rules, according to which banks needed to have stronger balance sheets to better handle shocks like the 2008 financial crisis, meaning the bank proportion of lending has declined.

That poses a risk to governments and companies around the world that have borrowed in dollars and now face a tougher time repaying those debts. “There is so much dollar debt outside the US globally, that policymakers around the world want to make sure that the currency does not strengthen further,” said Eric Stein, portfolio manager at Eaton Vance.

A third issue is related to the adverse impact on emerging market economic activity. IMF Managing Director K. Georgieva said: “Investors have already removed $ 83 billion from emerging markets since the beginning of the crisis, the largest capital outflow ever recorded.” The surge to the U.S. dollar has indeed driven several emerging countries’ currencies to record lows against the greenback in the last weeks, like the South African rand, Mexican peso and Brazilian real.

It is forecasted that although the dollar can probably remain elevated for now, the Fed’s aggressive response to the crisis could lead to a weaker dollar by the end of the year. However, one of the key questions in the short term is whether it is possible to find an alternative to the dollar dominance in our current monetary system.

One is to increase usage of another currency, but two competing currencies also cause several issues, especially in a crisis period. On the other hand, the concept of a basket-based digital currency or “Synthetic Hegemonic Currency” (SHC) would be an effective solution. Not only would it reduce the political risks of depending on the U.S. dollar, as well as economic risks purely associated with America, but also it should be more stable than a single currency.

A possible scenario is that outside the U.S., central banks might emerge from the pandemic shock with a stronger desire for independence from American influence over the global monetary system. It is highly unlikely the global monetary system would see a negotiated accord along the lines of the Bretton Woods accord, which was joined by 44 countries, as the state of national cooperation is pretty low. In order to make a big change in the monetary system, many countries would have to agree simultaneously, and everyone seems to be fending for themselves: Deep interest rate cuts and money injections by central banks in huge quantities appear to have become the default solution whenever a market crisis hits the financial system.

In conclusion, as no country has shown to be truly willing to initiate and steer such a conference to a globally satisfactory outcome, the inertia of incumbency favors the US dollar dominance also for the foreseeable future. Last but not least, from a geopolitical and geoeconomic viewpoint, the Covid-19 crisis will have weakened and not strengthened China by the end of the year; hence, probabilities that China, as well as any other country, could present itself as an acceptable alternative global hegemon and see their own currency replace the U.S. dollar are extremely low.

Annamaria Palmieri

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.