Historical Note

Investors and wealth managers have debated extensively which is the superior form of investing: active or passive. Historically, passive investing, otherwise known as indexing, has been shown to outperform active investing over time. Nonetheless, investors still see the value in active investing and there are portfolio managers that have consistently generated returns above benchmark. The goal of the portfolio manager of an actively managed fund is to achieve returns that surpass the fund’s benchmark while taking a calculated amount of risk. It is now commonly agreed that there is a role for both active and passive in a portfolio and the choice should be based on a number of factors.

Key Differences

There are significant differences between the two types of investing that any retail or institutional investor must consider before selecting the correct type for them. These relate to how each fund is managed and the fees associated with both. Actively managed funds depend upon fund managers carrying out in-depth research to identify which companies ought to be included in the portfolio and to rebalance it periodically. Since the goal of active funds is to beat the index, they offer the potential to generate higher returns. Passive funds, on the other hand, seek to deliver a return similar to its benchmark by tracking a basket of securities that comprise that index. The recent trend concerning how investors select the fund they want to invest in is based on which fund has the lowest fees while outperforming its benchmark and competitors. This results in investors consistently leaning towards passive funds for their low costs and performance. That is not to say there is no value for active funds. Mike Haslam, Head of Funds Distribution at Barclays, said: “It’s important to look at funds in terms of ‘value for money’. This can be applied to investments: active funds cost more than passive funds, but some are worth paying for, and others are not.

Two other factors that must be considered are transparency and the goal of the fund. As mentioned before, an active fund manager’s goal is to outperform a specific benchmark, whereas a passive fund attempts to mirror the performance of its benchmark. The performance of the market is also a relevant factor that must be considered. The benefit of having an active manager is that when the market is particularly volatile or underperforming, the manager may be able to generate alpha, whereas the passive fund will perform consistently as the market does. Passive funds do, however, have an advantage over active funds with respect to transparency. This is simply due to the goal of a passive fund is to track an index, so investors are able to view with ease the specific holdings and sector allocation within the fund. Active funds are less transparent because portfolio managers tend to be more reluctant to disclose holdings and other information so that competitors cannot mimic their investments. In general, active funds typically reveal their top 10 holdings and weighting of the fund each month to inform investors of their decisions.

Both types of funds have their benefits and drawbacks and while one may be suited for most investors it is not a “one size fits all”. Active management does present itself with higher costs but can be offset with the potential for outperformance. Passive management does allow for diversification at lower costs, but with that comes performance constraints and additional market risk.

Performance Drivers and Historical Performance

To evaluate the performance of active funds against passive funds, there are few but extremely clear drivers. First, the net inflows received measure the popularity of the instruments. Second, the actual performance of the instruments with respect to the market (ie if the active funds manage to beat their respective index, tracked by the passive funds). Third, the fees paid by the clients, which in the end are one of the core issues, since passive funds are much cheaper than active ones.

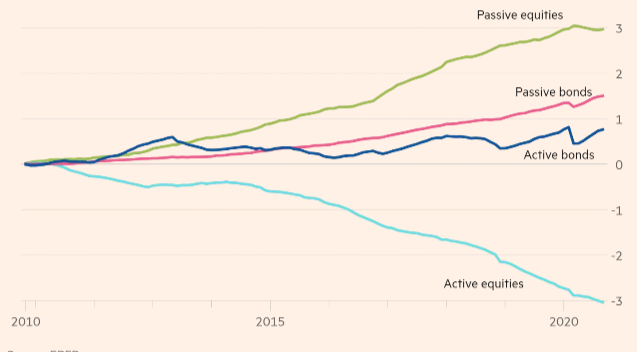

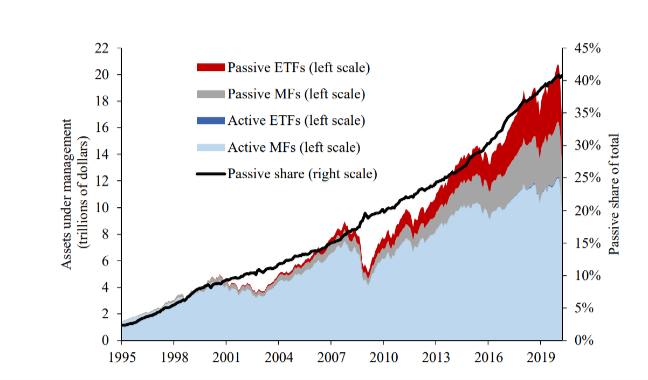

Looking at the net inflows received by active and passive funds, it is interesting to notice that the historical performance is not particularly in favour of active funds. Indeed, passive funds have attracted more and more inflows and clients, with passive equities being the largest winners and active equities the biggest losers. From EPFR data retrieved by the Financial Times, in the decade 2010-2020 passive equities gained $3tn while passive bonds gained almost $1.5tn, whereas active bonds managed to obtain less than $1tn and active equities lost $3 tn (Fig. 1). The Federal Reserve of Boston, using Morningstar data, highlights in one of its working papers how the passive share of total asset management has rapidly increased in the period 1995-2019 from less than 5% to almost 40% (Fig. 2). Therefore, historically speaking the clear winners have been passive funds, which have become more popular and widespread. Title Text. Clicca qui per modificare.

Investors and wealth managers have debated extensively which is the superior form of investing: active or passive. Historically, passive investing, otherwise known as indexing, has been shown to outperform active investing over time. Nonetheless, investors still see the value in active investing and there are portfolio managers that have consistently generated returns above benchmark. The goal of the portfolio manager of an actively managed fund is to achieve returns that surpass the fund’s benchmark while taking a calculated amount of risk. It is now commonly agreed that there is a role for both active and passive in a portfolio and the choice should be based on a number of factors.

Key Differences

There are significant differences between the two types of investing that any retail or institutional investor must consider before selecting the correct type for them. These relate to how each fund is managed and the fees associated with both. Actively managed funds depend upon fund managers carrying out in-depth research to identify which companies ought to be included in the portfolio and to rebalance it periodically. Since the goal of active funds is to beat the index, they offer the potential to generate higher returns. Passive funds, on the other hand, seek to deliver a return similar to its benchmark by tracking a basket of securities that comprise that index. The recent trend concerning how investors select the fund they want to invest in is based on which fund has the lowest fees while outperforming its benchmark and competitors. This results in investors consistently leaning towards passive funds for their low costs and performance. That is not to say there is no value for active funds. Mike Haslam, Head of Funds Distribution at Barclays, said: “It’s important to look at funds in terms of ‘value for money’. This can be applied to investments: active funds cost more than passive funds, but some are worth paying for, and others are not.

Two other factors that must be considered are transparency and the goal of the fund. As mentioned before, an active fund manager’s goal is to outperform a specific benchmark, whereas a passive fund attempts to mirror the performance of its benchmark. The performance of the market is also a relevant factor that must be considered. The benefit of having an active manager is that when the market is particularly volatile or underperforming, the manager may be able to generate alpha, whereas the passive fund will perform consistently as the market does. Passive funds do, however, have an advantage over active funds with respect to transparency. This is simply due to the goal of a passive fund is to track an index, so investors are able to view with ease the specific holdings and sector allocation within the fund. Active funds are less transparent because portfolio managers tend to be more reluctant to disclose holdings and other information so that competitors cannot mimic their investments. In general, active funds typically reveal their top 10 holdings and weighting of the fund each month to inform investors of their decisions.

Both types of funds have their benefits and drawbacks and while one may be suited for most investors it is not a “one size fits all”. Active management does present itself with higher costs but can be offset with the potential for outperformance. Passive management does allow for diversification at lower costs, but with that comes performance constraints and additional market risk.

Performance Drivers and Historical Performance

To evaluate the performance of active funds against passive funds, there are few but extremely clear drivers. First, the net inflows received measure the popularity of the instruments. Second, the actual performance of the instruments with respect to the market (ie if the active funds manage to beat their respective index, tracked by the passive funds). Third, the fees paid by the clients, which in the end are one of the core issues, since passive funds are much cheaper than active ones.

Looking at the net inflows received by active and passive funds, it is interesting to notice that the historical performance is not particularly in favour of active funds. Indeed, passive funds have attracted more and more inflows and clients, with passive equities being the largest winners and active equities the biggest losers. From EPFR data retrieved by the Financial Times, in the decade 2010-2020 passive equities gained $3tn while passive bonds gained almost $1.5tn, whereas active bonds managed to obtain less than $1tn and active equities lost $3 tn (Fig. 1). The Federal Reserve of Boston, using Morningstar data, highlights in one of its working papers how the passive share of total asset management has rapidly increased in the period 1995-2019 from less than 5% to almost 40% (Fig. 2). Therefore, historically speaking the clear winners have been passive funds, which have become more popular and widespread. Title Text. Clicca qui per modificare.

Fig. 1 Cumulative net inflows over the past decade, bonds and equities ($tn)

Source: Financial Times

Fig. 2 Total assets in active and passive MFs and ETFs and passive share of total

Source: Federal Reserve of Boston

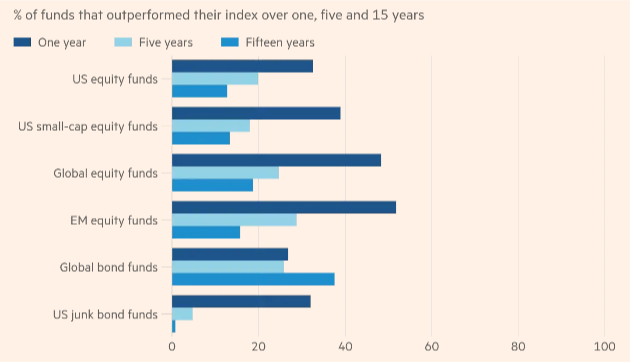

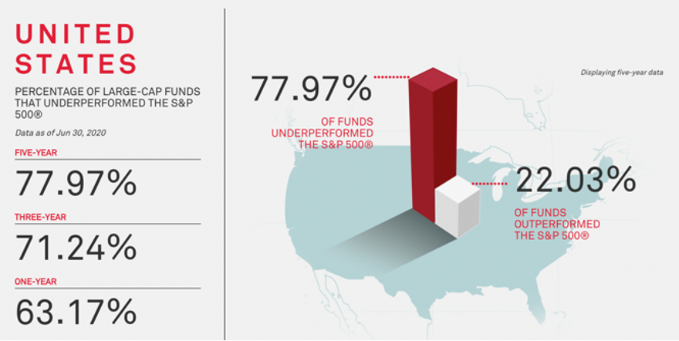

Passive funds track a specific index, from the S&P500 to small caps; therefore, they become the benchmark that active funds need to beat, and the performance of active funds against their respective indexes has been an indicator looked with anxiety by active asset managers. Based on data from the fund research firm Refinitiv Lipper and from the S&P500 Down Jones indices, active funds really have difficulties in beating their respective passive counterparts (Fig. 3. What it seems to lack in actives is consistency, with only few exceptions capable of showing overperformance over a longer period. According to SPIVA, over the past five years, 77.97% of large-cap funds in the United States underperformed the S&P 500 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3 Investment funds consistently struggle to beat their benchmarks

Source: Financial Times

Fig. 4 Percentage of large-cap funds that underperformed the S&P500

Source: SPIVA

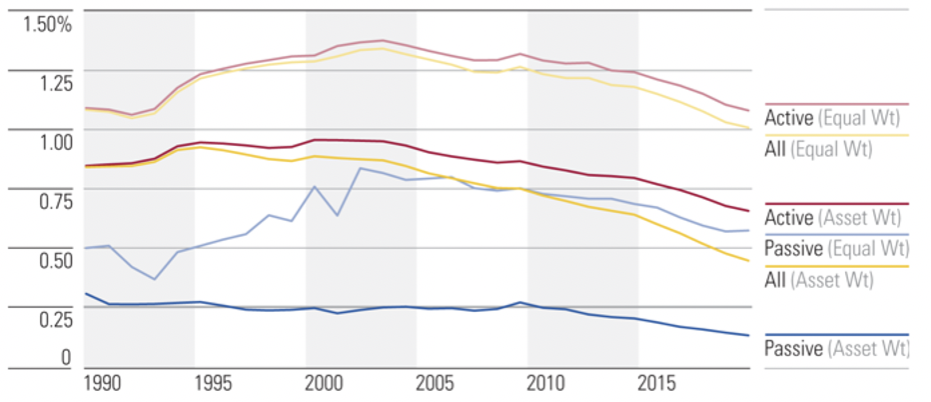

Finally, fees. As we can see from Morningstar data (Fig. 5), active management requires always higher fees compared to passive index tracking, and that is the real cost advantage of passives: by simply tracking a chosen index instead of stock picking, passives managed to lower fees and put cost pressure on actives. Investors typically will pay a higher cost basis for an actively managed fund, usually between 0.6% and 1.5%, for the expertise of the fund manager. Indeed, data show how the fees started to get lower even for actives, thus pushing active funds towards consolidation.

Fig. 5 Active management and Passive Management fees

Source: Morningstar

However, all of this is about historical performances, but how has the “war” between active and passive funds evolved during the COVID-19 crisis?

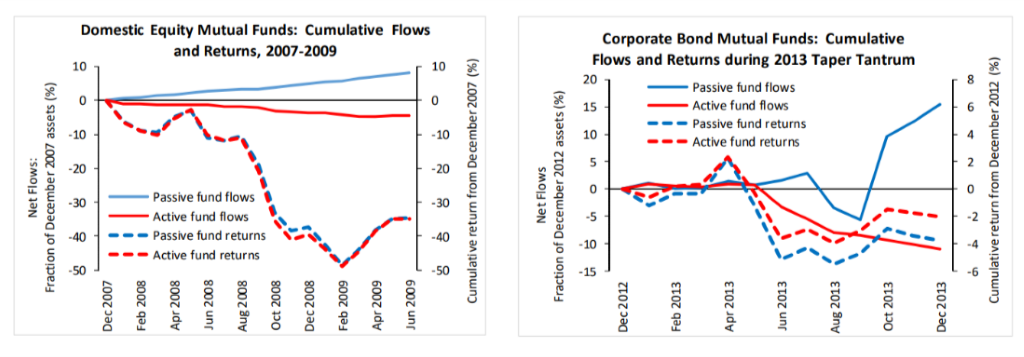

Active fund managers often argued that the real added value of active management is during downturns, where the stock picking becomes crucial to obtain outperformance and finally beat the market. According to the Federal Reserve of Boston’s working paper (Fig. 6), there is some truth to this. However, passive funds manage to suffer less from cash outflows in periods of downturn, while active funds get punished with outflows even if they manage to perform slightly better. This goes against the chant that overperformance will bring inflows but there could be a possible interpretation to this behaviour that seems unfair to active management. Passive funds’ clients might have more “trust” in the market and in index tracking, so even when the market becomes bearish, they remain committed to their passive management choice; on the other hand, active funds’ clients might be less committed to their fund choice, and when the tide turns, they decide either to change to another active fund, or to move to passives.

Active fund managers often argued that the real added value of active management is during downturns, where the stock picking becomes crucial to obtain outperformance and finally beat the market. According to the Federal Reserve of Boston’s working paper (Fig. 6), there is some truth to this. However, passive funds manage to suffer less from cash outflows in periods of downturn, while active funds get punished with outflows even if they manage to perform slightly better. This goes against the chant that overperformance will bring inflows but there could be a possible interpretation to this behaviour that seems unfair to active management. Passive funds’ clients might have more “trust” in the market and in index tracking, so even when the market becomes bearish, they remain committed to their passive management choice; on the other hand, active funds’ clients might be less committed to their fund choice, and when the tide turns, they decide either to change to another active fund, or to move to passives.

Fig. 6 Cumulative net flows and returns for active and passive MFs during periods of financial strain

Source: Federal Reserve of Boston

Did the same happened during this new crisis?

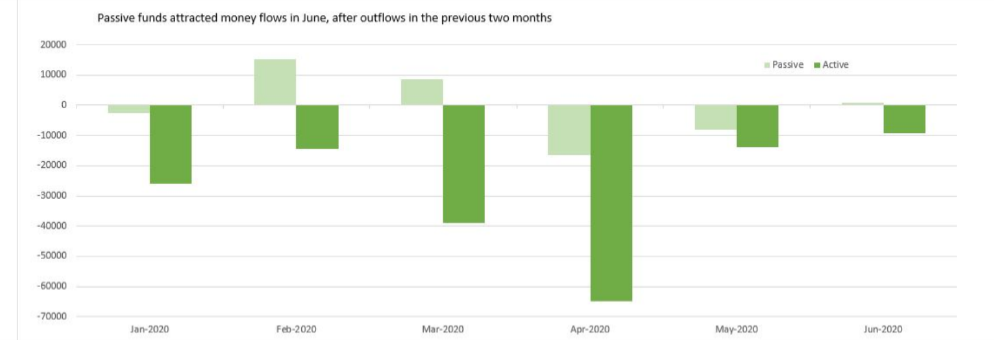

Surely, actives were again subject to a major round of outflows. According to Refinitiv Lipper (Fig. 7), both active funds and passive funds suffered outflows during the first quarter of 2020; however, while passive funds managed to invert the trend in June, with a small inflow of $860 mln, the drought has been persistent for active funds, with the lowest point reached in April, with almost $70 bln withdrawn from actives.

Surely, actives were again subject to a major round of outflows. According to Refinitiv Lipper (Fig. 7), both active funds and passive funds suffered outflows during the first quarter of 2020; however, while passive funds managed to invert the trend in June, with a small inflow of $860 mln, the drought has been persistent for active funds, with the lowest point reached in April, with almost $70 bln withdrawn from actives.

Fig. 7 Fund flows into US funds

Source: Refinitiv Lipper

Did the active funds manage to finally prove their worth and added value during this unprecedented crisis?

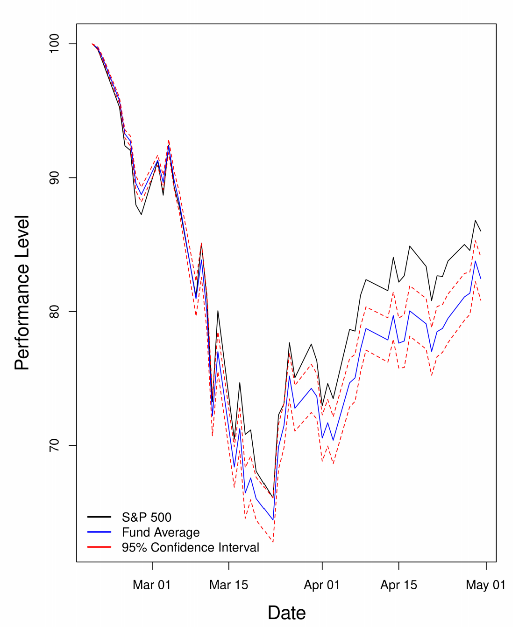

There is mixed evidence on this point. Booth School of Business’ professors Lubos Pastor and Blair Vorsatz have some interesting takes on this. According to their freshly published paper, active funds did not manage to beat the S&P500 (Fig. 8) or other benchmarks like the FTSE/Russell benchmark. This is no good news for actives, since this crisis could have been a great occasion to prove the common hypothesis that actively managed funds have a hedge in difficult times: indeed, COVID crisis has led to a sudden output contraction and to unexpected large price dislocation in the financial markets, with the indexes falling sharply. With many actives unable to prove their added value, the debate on active versus passive fund management seems again leaning on the passive side.

There is mixed evidence on this point. Booth School of Business’ professors Lubos Pastor and Blair Vorsatz have some interesting takes on this. According to their freshly published paper, active funds did not manage to beat the S&P500 (Fig. 8) or other benchmarks like the FTSE/Russell benchmark. This is no good news for actives, since this crisis could have been a great occasion to prove the common hypothesis that actively managed funds have a hedge in difficult times: indeed, COVID crisis has led to a sudden output contraction and to unexpected large price dislocation in the financial markets, with the indexes falling sharply. With many actives unable to prove their added value, the debate on active versus passive fund management seems again leaning on the passive side.

Fig. 8 Performance of funds against the S&P500 during the first semester of 2020

Source: Pastor, Vorsatz, Mutual Fund Performance and Flows during the COVID-19 Crisis

However, not all is lost for actives. Indeed, the performances are extremely heterogeneous, and the authors of the paper found that, even though overall active funds have underperformed, two specific kind of funds succeeded in obtaining overperformance.

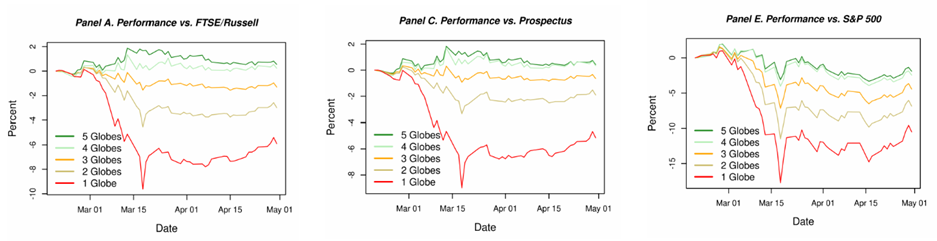

The first group is composed of ESG-based or sustainable funds. Looking at the ratings given by Morningstar (with “1 globe” being the least sustainable and “5 globes” the most sustainable), data show how the most sustainable funds achieved overperformance against their benchmark (“prospectus”) and against the FTSE/Russell index (Fig. 9).

The first group is composed of ESG-based or sustainable funds. Looking at the ratings given by Morningstar (with “1 globe” being the least sustainable and “5 globes” the most sustainable), data show how the most sustainable funds achieved overperformance against their benchmark (“prospectus”) and against the FTSE/Russell index (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9 Performance of 1-5 globe funds against FTSE/Russell, their benchmark, and the S&P500

Source: Pastor, Vorsatz, Mutual Fund Performance and Flows during the COVID-19 Crisis

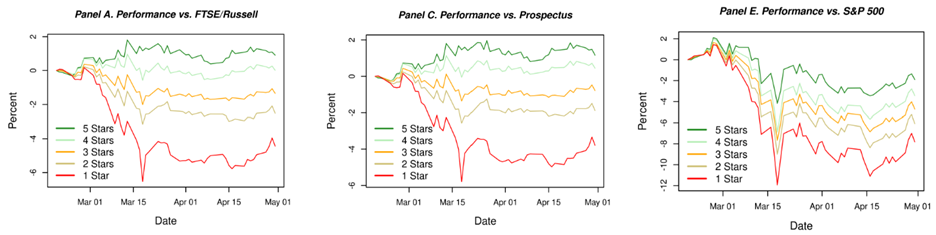

The second group consists in the funds that received a positive rating or an indication of their quality, such as the one used by Morningstar (with “1 star” being indicator of low quality and “5 stars” being indicator of high quality in terms of risk-adjusted returns). As for the previous group, these funds managed to beat their benchmark and the FTSE/Russell index (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10 Performance of 1-5 star funds against FTSE/Russell, their benchmark, and the S&P500

Source: Pastor, Vorsatz, Mutual Fund Performance and Flows during the COVID-19 Crisis

Therefore, while the overall result seems to be negative for actively managed funds, the paper sheds some light on very specific kind of funds, thus giving some hope to stock pickers.

Hedge Funds facing difficulties to deliver satisfactory returns for their investors

As noted, before, even within active funds there exist a high variability in the extent to which the manager is allowed to deviate from the benchmark portfolios by using its own discretion in making investment decisions. Among these, Hedge funds are those that grant the highest freedom to their professionals who may decide to enter short positions or even assume binary exposures to almost-defaulted companies. While this has created opportunities for extraordinary returns in the past, there is evidence that the industry may be losing its charm.

There are extraordinary examples of how in the past HFs have overperformed any other asset class. John Paulson’s bet against mortgages in 2007 is a representative example of this as the fund took home c. 15 billion on a single deal. This, together with other extraordinary stories of success, justify the industry’s growth over the past 30 years. Total assets under management (AUM) increased from 39 billion USD in mid ‘90s up to more than 3 trillion as of today and the number of funds skyrocketed from 2001 to 2007 up to eight thousand units. This growth of the industry comes with high attrition rates. Given the high-risk investments targeted by HFs, different researchers find a mortality rate of around 8%, indicating that on average 8 out of 100 HFs make such wrong investment decisions to incur in losses they are unable to sustain.

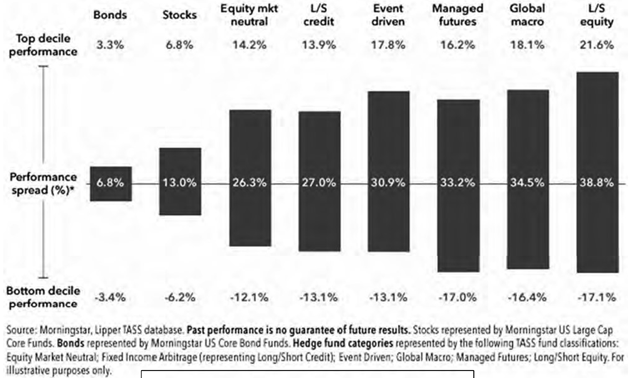

Despite most investors have been drawn to HFs by the record of attractive returns, there are parties who have voiced concerns about the effective ability of HFs to generate positive excess returns in the long-term and investing in other asset classes may be a better option. This is particularly true if we mitigate stories of success with failures over time and if we account for the 20% performance fee on capital appreciation and 2% management fee that HFs on average charge to their participants. The critique that Hedge Funds are becoming increasingly unable to deliver a satisfactory risk-adjusted performance holds true for all the different typologies of HFs’ strategies reported in the figure below (Fig.11).

Hedge Funds facing difficulties to deliver satisfactory returns for their investors

As noted, before, even within active funds there exist a high variability in the extent to which the manager is allowed to deviate from the benchmark portfolios by using its own discretion in making investment decisions. Among these, Hedge funds are those that grant the highest freedom to their professionals who may decide to enter short positions or even assume binary exposures to almost-defaulted companies. While this has created opportunities for extraordinary returns in the past, there is evidence that the industry may be losing its charm.

There are extraordinary examples of how in the past HFs have overperformed any other asset class. John Paulson’s bet against mortgages in 2007 is a representative example of this as the fund took home c. 15 billion on a single deal. This, together with other extraordinary stories of success, justify the industry’s growth over the past 30 years. Total assets under management (AUM) increased from 39 billion USD in mid ‘90s up to more than 3 trillion as of today and the number of funds skyrocketed from 2001 to 2007 up to eight thousand units. This growth of the industry comes with high attrition rates. Given the high-risk investments targeted by HFs, different researchers find a mortality rate of around 8%, indicating that on average 8 out of 100 HFs make such wrong investment decisions to incur in losses they are unable to sustain.

Despite most investors have been drawn to HFs by the record of attractive returns, there are parties who have voiced concerns about the effective ability of HFs to generate positive excess returns in the long-term and investing in other asset classes may be a better option. This is particularly true if we mitigate stories of success with failures over time and if we account for the 20% performance fee on capital appreciation and 2% management fee that HFs on average charge to their participants. The critique that Hedge Funds are becoming increasingly unable to deliver a satisfactory risk-adjusted performance holds true for all the different typologies of HFs’ strategies reported in the figure below (Fig.11).

Fig. 11 Risk-adjusted performance for different hedge funds

Source: Morningstar, Lipper TASS database

As shown in the chart, hedge funds with most aggressive strategies tend to display higher variance of returns with respect to HFs with a lower-risk investment profile. To mention an example, Global macro which trades currencies, futures and commodities in an attempt to take advantage of macroeconomic trends displays a higher risk than equity market neutral, which more simply enters long and short positions on over and undervalued equities in order to achieve neutral exposure to market risk.

Why are Hedge Funds going through hard times?

Since mid 90s’ HFs’ average returns have been declining steadily and the average monthly alpha of the industry (i.e., the additional return that is achieved by the funds after accounting for all risk factors and their corresponding exposures) has entered the negative region at -0.07%. This implies that the active contribution of fund managers has destroyed value with respect to the results achievable without active management.

Some argue that, given the increasingly dominant position of HFs and the consequential increasing risk that they may destabilize financial markets, it is reasonable to expect tighter regulation for the industry. Indeed, the holdings of HFs in publicly traded stocks have skyrocketed in the last 10 years. This poses a risk for the stability of financial markets as it is not infrequent to have HFs go from a long to a short position on all their stake unexpectedly. According to this line of thought, Hedge Funds’ overperformance in the past was solely justified by a more favourable regulatory environment which is now fading away due to the increasing risk that the industry poses on the stability of financial markets. For example, the frequent statutory prohibition of traditional mutual funds to short securities may have limited the set of investment opportunities that can be accessed by this investment vehicles, hence reducing the opportunities to achieve returns as high as those of speculative hedge funds. This interpretation is supported by a convergency of the Sharpe ratios of the two investment vehicles- Hedge Funds and Mutual Funds- in recent years.

In an attempt to compensate for the low interest rates environment, institutional investors have commenced to be interested in the products offered by Hedge Funds as their traditional investments where not yielding sufficient returns anymore. This shift in HF’s clientele may be detrimental of the HF’s risk-adjusted performance as the risk-taking preferences of the vehicle will inevitably adapt to its new clientele. Insurance companies, pension funds and other institutional investors have long term liabilities with low or absent risk and attempt to adapt their assets to the risk and maturity profile of their obligations. Hence, it is reasonable to expect they will put increasing pressures on HFs’ managers to make the strategies more compliant with their own needs.

Another driver of HF underperformance must be identified in the increasing size of most individual HFs combined with a higher number of funds pursuing similar strategies. As more money is chasing investment opportunities with similar risk profiles, these become more expensive and consequently less attractive. Indeed, most practitioners argue that the actual popularity of the industry is simply the result of the record results produced when the industry was nascent. The sector is now mature and true outperformers are harder to find.

Lastly, there are professionals blaming unexpected monetary policy interventions as a reason for their underperformance. Recent macroeconomic trends would have therefore worked against fund managers not achieving satisfactory alphas. Indeed, managers entering a position based on a certain macroeconomics’ expectation, may reveal totally wrong when the unexpected monetary policy takes place.

How Covid-19 and Brexit will impact UK-based HF managers?

When it comes to geographically locate the most attractive Hedge Funds, the US has certainly a leading position and the UK is often referred to as the “slightly little brother to the US”, as mentioned by David Harding, founder of the Winton Group. However, among European players, UK-based Hedge Funds are those with the highest AUM and the best practitioners and there is reason to believe that this is about to change following Brexit and the effects of Covid-19.

Legal experts suggest that the incoming deadline of the EU-UK talks for post Brexit agreements is likely to further damage the industry. What has happened until now is that most funds were located in continental Europe while being managed by UK-based investment managers. These arrangements were favourable for managers as they allowed to benefit of the more advantageous legislation and corporate laws that other EU countries such as Luxemburg and Ireland offered. However, the EU competition and market authority has issued recommendations to limit this best practice as discussion over the UK-EU trade agreements proceed. Therefore, UK funds are about to be further damaged with respect to their US competitors as they lose this source of competitive advantage. This is also likely to imply a move of investment professionals from the UK to other EU countries where funds are legally located. An example of this is the London- Based H2O Asset Manager which opened an office in Paris and is considering relocating investment professionals there.

Moreover, as most EU regulations to protect retail investors limits the possibility to market a fund located outside the European union directly to final customers, Brexit is likely to materialize in increasing difficulties to raise additional funds in Europe for a London-Based firm. This should further accentuate the incentive to relocate.

Finally, Covid-19 has further increased the performance gap between the UK and the US since its impact has been disproportionate on the London sector. Travel restrictions are also damaging UK managers. Indeed, an increasing number of investors is becoming more reluctant to delegate the management of its capital without first meeting in person with those in charge of running the fund. These attempts to perform more detailed in-site due diligence, together with a better performance of US funds, make it more likely for large US institutional investors to be less tempted to place their capitals in Europe.

Conclusion

This article has introduced the differences between active funds and passive funds, and the historical debate that surrounds the choice between these two radically different ways of investing, and the pros and cons for each. Next, by looking at some key drivers like net inflows, performance, and fees, the article has provided an analysis of the historical performances of actives and passive.

Then, the article has focused on two different aspects. On one hand, the general performance of actives during the COVID crisis. The article explains how empirical evidence suggests that, while actives suffered during the first half of the year with respect to their benchmarks, some specific funds managed to outperform. On the other hand, the performance of hedge funds. The article describes the difficulties of hedge funds to achieve superior returns despite the high risks taken, and it mentions the tough times that UK-based hedge funds might face due to both COVID and Brexit.

Lilit Sarucanian

Nicola Bulgarelli

Nicolas Lockhart

Why are Hedge Funds going through hard times?

Since mid 90s’ HFs’ average returns have been declining steadily and the average monthly alpha of the industry (i.e., the additional return that is achieved by the funds after accounting for all risk factors and their corresponding exposures) has entered the negative region at -0.07%. This implies that the active contribution of fund managers has destroyed value with respect to the results achievable without active management.

Some argue that, given the increasingly dominant position of HFs and the consequential increasing risk that they may destabilize financial markets, it is reasonable to expect tighter regulation for the industry. Indeed, the holdings of HFs in publicly traded stocks have skyrocketed in the last 10 years. This poses a risk for the stability of financial markets as it is not infrequent to have HFs go from a long to a short position on all their stake unexpectedly. According to this line of thought, Hedge Funds’ overperformance in the past was solely justified by a more favourable regulatory environment which is now fading away due to the increasing risk that the industry poses on the stability of financial markets. For example, the frequent statutory prohibition of traditional mutual funds to short securities may have limited the set of investment opportunities that can be accessed by this investment vehicles, hence reducing the opportunities to achieve returns as high as those of speculative hedge funds. This interpretation is supported by a convergency of the Sharpe ratios of the two investment vehicles- Hedge Funds and Mutual Funds- in recent years.

In an attempt to compensate for the low interest rates environment, institutional investors have commenced to be interested in the products offered by Hedge Funds as their traditional investments where not yielding sufficient returns anymore. This shift in HF’s clientele may be detrimental of the HF’s risk-adjusted performance as the risk-taking preferences of the vehicle will inevitably adapt to its new clientele. Insurance companies, pension funds and other institutional investors have long term liabilities with low or absent risk and attempt to adapt their assets to the risk and maturity profile of their obligations. Hence, it is reasonable to expect they will put increasing pressures on HFs’ managers to make the strategies more compliant with their own needs.

Another driver of HF underperformance must be identified in the increasing size of most individual HFs combined with a higher number of funds pursuing similar strategies. As more money is chasing investment opportunities with similar risk profiles, these become more expensive and consequently less attractive. Indeed, most practitioners argue that the actual popularity of the industry is simply the result of the record results produced when the industry was nascent. The sector is now mature and true outperformers are harder to find.

Lastly, there are professionals blaming unexpected monetary policy interventions as a reason for their underperformance. Recent macroeconomic trends would have therefore worked against fund managers not achieving satisfactory alphas. Indeed, managers entering a position based on a certain macroeconomics’ expectation, may reveal totally wrong when the unexpected monetary policy takes place.

How Covid-19 and Brexit will impact UK-based HF managers?

When it comes to geographically locate the most attractive Hedge Funds, the US has certainly a leading position and the UK is often referred to as the “slightly little brother to the US”, as mentioned by David Harding, founder of the Winton Group. However, among European players, UK-based Hedge Funds are those with the highest AUM and the best practitioners and there is reason to believe that this is about to change following Brexit and the effects of Covid-19.

Legal experts suggest that the incoming deadline of the EU-UK talks for post Brexit agreements is likely to further damage the industry. What has happened until now is that most funds were located in continental Europe while being managed by UK-based investment managers. These arrangements were favourable for managers as they allowed to benefit of the more advantageous legislation and corporate laws that other EU countries such as Luxemburg and Ireland offered. However, the EU competition and market authority has issued recommendations to limit this best practice as discussion over the UK-EU trade agreements proceed. Therefore, UK funds are about to be further damaged with respect to their US competitors as they lose this source of competitive advantage. This is also likely to imply a move of investment professionals from the UK to other EU countries where funds are legally located. An example of this is the London- Based H2O Asset Manager which opened an office in Paris and is considering relocating investment professionals there.

Moreover, as most EU regulations to protect retail investors limits the possibility to market a fund located outside the European union directly to final customers, Brexit is likely to materialize in increasing difficulties to raise additional funds in Europe for a London-Based firm. This should further accentuate the incentive to relocate.

Finally, Covid-19 has further increased the performance gap between the UK and the US since its impact has been disproportionate on the London sector. Travel restrictions are also damaging UK managers. Indeed, an increasing number of investors is becoming more reluctant to delegate the management of its capital without first meeting in person with those in charge of running the fund. These attempts to perform more detailed in-site due diligence, together with a better performance of US funds, make it more likely for large US institutional investors to be less tempted to place their capitals in Europe.

Conclusion

This article has introduced the differences between active funds and passive funds, and the historical debate that surrounds the choice between these two radically different ways of investing, and the pros and cons for each. Next, by looking at some key drivers like net inflows, performance, and fees, the article has provided an analysis of the historical performances of actives and passive.

Then, the article has focused on two different aspects. On one hand, the general performance of actives during the COVID crisis. The article explains how empirical evidence suggests that, while actives suffered during the first half of the year with respect to their benchmarks, some specific funds managed to outperform. On the other hand, the performance of hedge funds. The article describes the difficulties of hedge funds to achieve superior returns despite the high risks taken, and it mentions the tough times that UK-based hedge funds might face due to both COVID and Brexit.

Lilit Sarucanian

Nicola Bulgarelli

Nicolas Lockhart