As the global economy progresses through the current COVID-19 crisis, we are constantly inundated by new information – and it can be easy to lose sight of the bigger picture. This article aims at providing a clear summary of the major happenings until now and help the reader understand where to look in order to monitor the recovery.

The article is structured in three complementary parts: Impact on the Real Economy, Central Banks and Governments’ reactions – and Key Indicators, where we present what, in our opinion, are the best indicators to be monitored in order to gauge the health of the economy.

The article is structured in three complementary parts: Impact on the Real Economy, Central Banks and Governments’ reactions – and Key Indicators, where we present what, in our opinion, are the best indicators to be monitored in order to gauge the health of the economy.

IMPACT ON THE REAL ECONOMY

|

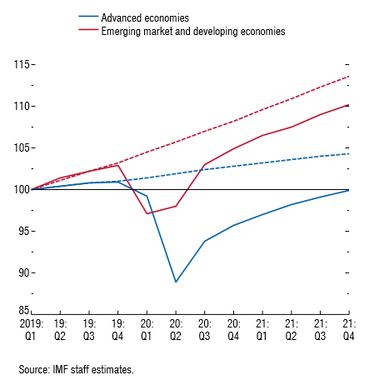

The world economy is expected to undergo a severe slump in the next months, caused by a forced halt of economic activity in numerous countries. Forecasts are nonetheless extremely uncertain – being based on assumptions that can change in a matter of days.

According to the World Economic Outlook report published by IMF in April 2020, projections on world GDP sign a -3%, which is a staggering figure compared to the relatively small -1.68% experienced during the 2009 financial crisis. Advanced economies will be the most affected, signing a -6.1%, while emerging economies will withstand better the shock, showing a -1%. If the health crisis fades in 2020, IMF expects world GDP to bounce 5.8% in 2021 thanks to the normalization of production and economic activity. Let’s take a detailed look at some of the main economies worldwide. |

CHINA

GDP Forecasts

Before the outbreak expanded, China’s prospects were in line with previous years’ growth. In January, analysts’ consensus, as reported by FactSet, was that the economy would have expanded 5.9%. However, the situation degenerated quickly, and, since then, it has been difficult to forecast even basic economic measures, such as GDP. China was the first country to impose a halt to its economic activity in order to curb the spread of the pandemic, leading some analysts to predict up to -16% output in the first quarter. According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, national GDP reached a loss of 6.8% year-over-year in the first three months of 2020. This result is extremely significant, given that the Chinese economy did not post a contraction in GDP since 1976, and 2020 could sign the end of almost half-century of growth.

Given the current situation of uncertainty, the government refrained even from setting its yearly economic growth targets, which are usually communicated in early March. Consensus over Chinese GDP growth is widely dispersed, but has stabilized towards lower and lower levels since the beginning of the outbreak. In March, the median value for Chinese growth, according to over 50 estimates by financial institutions, was +3.2%. In May, the median forecast for growth in 2020, as reported by FactSet, was halved, +1.6%. Also, the IMF foresees a similar number, +1.2%. Among the worst estimates there is the one provided by Banca d’Italia, the Italian central bank, according to which the country’s GDP will slump -4.8%.

Despite bleak prospects for the current year, the country is expected to be back on its growth path starting from 2021, where it is predicted to bounce back to a 6.5% growth.

Import-Export

The first quarter has been particularly tough for Chinese export-oriented firms. In January and February, exports dropped 15.9% year-over-year and exports towards the US slumped more than 25% in the first quarter. Imports, according to FactSet, went down just by 1.7%. Due to the enactment of phase one trade deal signed in January, imports towards the US declined just by 1.3%.

In March, however, the situation seemed to be improving, with exports down just by 3.5%. Also, the trade balance improved to an $18.5bn surplus, from the $7.1bn deficit in the previous two months. Yet, caution in reaching conclusions is needed since the US and Europe are still in lockdown. If in January and February the declined exports were due to difficulties on the supply side in China, in the following months we can witness a crisis on the demand side from the US and Europe themselves.

UNITED STATES

GDP Forecasts

The main value driver behind forecasts for the United States is the coronavirus pandemic. Expert consensus is that the reaction of the country to the outbreak was belated, which will weigh on the post-virus recovery, slowing it down significantly. On the other hand, the government is predicting a very rapid V-shaped upturn, which is also consistent with the president’s intentions to loosen restrictions very early into the virus. According to the outlook published by the Congressional Budget Office in January, the 2020 inflation-adjusted GDP was projected to grow by 2.2 percent, largely because of continued strength in consumer spending and a rebound in business fixed investment. This now seems unlikely given recent developments in the macro-environment.

The IMF projects a -5.9% reduction in GDP for 2020, which is then followed by a significant positive rebound of 4.7% the following year. This scenario seems to mirror the outlook communicated by the United States government, that the economy would undergo a quick recovery. The trends delineated by the IMF conform to the forecasts issued by the largest financial institutions. Namely, banks also support the claim that there would be a V-shaped recovery, based importantly on clear signs that economic activity in China is quickly returning to normal. There isn’t, however, consensus as to how deep of a recession would the US fall into this year. The most pessimistic view is presented by Goldman Sachs, which foresees that GDP is going to fall to 9% in the first quarter, followed by a stunning 34% plunge in the second quarter that would be by far the worst period in post-World War II history. On the other hand, Bank of America’s base case is a near 25% drop in second-quarter GDP, while JPMorgan Chase predicts a 14% decline.

We utilized FactSet to assess the views of other players as well. FactSet’s database includes GDP estimates issued by the major financial institutions for the year 2020. We present our results based on forecasts issued in April 2020 from 12 financial institutions: Evercore, Unicredit, Nomura, Jefferies, Banca D’Italia, ING Wholesale Banking, Bank of the West, Scotiabank, CIBC, TD Economics, Oddo BHF Corporates & Markets, NBG. The GDP forecasts range from -6.0% to -16.0%, with a median of -6.1% and a mean of -8.0%. Important to mention, that these estimates were revised down from the previous corresponding figures in all of the cases. However, if we extend the research to 63 data providers, we arrive at a median of -3.1%. The difference is very marked and shows that financial institutions gauge the gravity of the situation very differently.

One thing is sure: the pronounced discrepancies between the forecasts reflect the uncertainty that surrounds the US economy, which makes predictions subject to speculations.

Import-Export

There are several factors at play when it comes to exports and imports. First of all, the coronavirus has virtually hit the whole Planet, therefore growth will foreseeably slump everywhere. This results in reduced cross-border products and services flow and disrupted supply chains. Secondly, the US is escalating the trade war against China, its largest trade partner, which is likely to have unforeseen consequences on its economy.

Globally, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is predicting a severe decline in international trade this year, and the US is no exception. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in January 2020 both exports and imports saw a significant decline compared to December, with $0.9 billion and $4.2 billion less value flows respectively. The pandemic seems to exacerbate the disruptions caused by the trade war with China. Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) found that $3.3 billion in imports of critical health-care products still face 7.5% tariffs, while $1.1 billion of imports which could potentially treat COVID-19 remained subjected to 25% tariffs. Also, there is a significant dependence not only on medical equipment but also on medicaments. The White House trade adviser Peter Navarro stated that 97% of antibiotics sold in the United States were imported from China. Due to the gravity and the urgency of the situation the US is currently facing, several notable market players, like General Motors, have pushed for an easing in trade tensions. As a result, the United States Trade Representative has in recent weeks granted “Section 301” tariff exclusions for certain medical products from China, including medical masks, examination gloves, and antiseptic wipes. This comes as a surprise knowing the President’s hard stance on the trade relations with China and may have further repercussions in this year’s presidential race.

EUROZONE

GDP Forecasts

According to the forecasts published by the International Monetary Fund, Eurozone - considered as a whole - will see GDP declining by 7.5% in 2020, while a rebound of 4,7% has been estimated for the following year. Forecasts provided by FactSet are instead more optimistic: outlook for Eurozone real GDP is -5.2% in 2020 and, after a drop by 3.5% in the first quarter followed by dramatic fall by 10.0% in the second one, a rebound of Eurozone GDP is expected in the third quarter (+8.3%).

Before the global outbreak of the virus, growth in the euro area was projected to pick up from 1.2% in 2019 to 1.3% this year. However, the uncertainty related to these previsions is extremely high. Until now, there have been drastic measures taken to contain the virus and to enable healthcare systems to face it, such as quarantine and partial lockdowns. As a consequence, the impact on economic activity is severe and we are seeing its first results.

Italy is one of the countries which will suffer the most: IMF predicted a GDP contraction of 9.1%. Comparing this forecast with the other Eurozone states, it turns out that only Greece was estimated to be hit by a larger contraction (10%). In Italy all non-essential activities were halted on March 23rd. After that, the recovery has taken place very gradually: on May 4th macro-sectors of construction and manufacturing were restarted, while other non-essential activities reopened only on May 18th. Without considering indirect effects, the lockdown alone is estimated to cut 0.5% a week from annual GDP. In addition, indirect effects are several but the most worrisome is tourism (13.2% of Italy’s GDP), which is expected to be severely hit by travel restrictions during the summer period.

Moreover, looking at the countries outside Europe, only three present slumps worse than the one predicted for Italy: Lebanon (-12%), Venezuela (-15%) and Macao (-29,6%).

Concerning other EU countries, German economy is projected to drop by 7,0%, similar to France, for which forecast is -7.2% of its annual GDP. Even Spain will see a fall and, according to IFM previsions, it will be about 8.0%.

Import-Export

Regarding import and export activities of the EU, the European Commission has issued its previsions. In particular, they said that Eurozone export of goods and services will decline by 9.2%, for an amount of €285bn, while imports of goods and services will decrease by 8.8%, or €240bn. This projection is based on the belief of the Commission that global trade will reduce by 9.7%. However, the World Trade Organization has estimated a drop of world trade between 13% and 32% during this year, as a consequence of Covid-19 outbreak worldwide.

GDP Forecasts

Before the outbreak expanded, China’s prospects were in line with previous years’ growth. In January, analysts’ consensus, as reported by FactSet, was that the economy would have expanded 5.9%. However, the situation degenerated quickly, and, since then, it has been difficult to forecast even basic economic measures, such as GDP. China was the first country to impose a halt to its economic activity in order to curb the spread of the pandemic, leading some analysts to predict up to -16% output in the first quarter. According to the Chinese National Bureau of Statistics, national GDP reached a loss of 6.8% year-over-year in the first three months of 2020. This result is extremely significant, given that the Chinese economy did not post a contraction in GDP since 1976, and 2020 could sign the end of almost half-century of growth.

Given the current situation of uncertainty, the government refrained even from setting its yearly economic growth targets, which are usually communicated in early March. Consensus over Chinese GDP growth is widely dispersed, but has stabilized towards lower and lower levels since the beginning of the outbreak. In March, the median value for Chinese growth, according to over 50 estimates by financial institutions, was +3.2%. In May, the median forecast for growth in 2020, as reported by FactSet, was halved, +1.6%. Also, the IMF foresees a similar number, +1.2%. Among the worst estimates there is the one provided by Banca d’Italia, the Italian central bank, according to which the country’s GDP will slump -4.8%.

Despite bleak prospects for the current year, the country is expected to be back on its growth path starting from 2021, where it is predicted to bounce back to a 6.5% growth.

Import-Export

The first quarter has been particularly tough for Chinese export-oriented firms. In January and February, exports dropped 15.9% year-over-year and exports towards the US slumped more than 25% in the first quarter. Imports, according to FactSet, went down just by 1.7%. Due to the enactment of phase one trade deal signed in January, imports towards the US declined just by 1.3%.

In March, however, the situation seemed to be improving, with exports down just by 3.5%. Also, the trade balance improved to an $18.5bn surplus, from the $7.1bn deficit in the previous two months. Yet, caution in reaching conclusions is needed since the US and Europe are still in lockdown. If in January and February the declined exports were due to difficulties on the supply side in China, in the following months we can witness a crisis on the demand side from the US and Europe themselves.

UNITED STATES

GDP Forecasts

The main value driver behind forecasts for the United States is the coronavirus pandemic. Expert consensus is that the reaction of the country to the outbreak was belated, which will weigh on the post-virus recovery, slowing it down significantly. On the other hand, the government is predicting a very rapid V-shaped upturn, which is also consistent with the president’s intentions to loosen restrictions very early into the virus. According to the outlook published by the Congressional Budget Office in January, the 2020 inflation-adjusted GDP was projected to grow by 2.2 percent, largely because of continued strength in consumer spending and a rebound in business fixed investment. This now seems unlikely given recent developments in the macro-environment.

The IMF projects a -5.9% reduction in GDP for 2020, which is then followed by a significant positive rebound of 4.7% the following year. This scenario seems to mirror the outlook communicated by the United States government, that the economy would undergo a quick recovery. The trends delineated by the IMF conform to the forecasts issued by the largest financial institutions. Namely, banks also support the claim that there would be a V-shaped recovery, based importantly on clear signs that economic activity in China is quickly returning to normal. There isn’t, however, consensus as to how deep of a recession would the US fall into this year. The most pessimistic view is presented by Goldman Sachs, which foresees that GDP is going to fall to 9% in the first quarter, followed by a stunning 34% plunge in the second quarter that would be by far the worst period in post-World War II history. On the other hand, Bank of America’s base case is a near 25% drop in second-quarter GDP, while JPMorgan Chase predicts a 14% decline.

We utilized FactSet to assess the views of other players as well. FactSet’s database includes GDP estimates issued by the major financial institutions for the year 2020. We present our results based on forecasts issued in April 2020 from 12 financial institutions: Evercore, Unicredit, Nomura, Jefferies, Banca D’Italia, ING Wholesale Banking, Bank of the West, Scotiabank, CIBC, TD Economics, Oddo BHF Corporates & Markets, NBG. The GDP forecasts range from -6.0% to -16.0%, with a median of -6.1% and a mean of -8.0%. Important to mention, that these estimates were revised down from the previous corresponding figures in all of the cases. However, if we extend the research to 63 data providers, we arrive at a median of -3.1%. The difference is very marked and shows that financial institutions gauge the gravity of the situation very differently.

One thing is sure: the pronounced discrepancies between the forecasts reflect the uncertainty that surrounds the US economy, which makes predictions subject to speculations.

Import-Export

There are several factors at play when it comes to exports and imports. First of all, the coronavirus has virtually hit the whole Planet, therefore growth will foreseeably slump everywhere. This results in reduced cross-border products and services flow and disrupted supply chains. Secondly, the US is escalating the trade war against China, its largest trade partner, which is likely to have unforeseen consequences on its economy.

Globally, the World Trade Organization (WTO) is predicting a severe decline in international trade this year, and the US is no exception. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, in January 2020 both exports and imports saw a significant decline compared to December, with $0.9 billion and $4.2 billion less value flows respectively. The pandemic seems to exacerbate the disruptions caused by the trade war with China. Peterson Institute for International Economics (PIIE) found that $3.3 billion in imports of critical health-care products still face 7.5% tariffs, while $1.1 billion of imports which could potentially treat COVID-19 remained subjected to 25% tariffs. Also, there is a significant dependence not only on medical equipment but also on medicaments. The White House trade adviser Peter Navarro stated that 97% of antibiotics sold in the United States were imported from China. Due to the gravity and the urgency of the situation the US is currently facing, several notable market players, like General Motors, have pushed for an easing in trade tensions. As a result, the United States Trade Representative has in recent weeks granted “Section 301” tariff exclusions for certain medical products from China, including medical masks, examination gloves, and antiseptic wipes. This comes as a surprise knowing the President’s hard stance on the trade relations with China and may have further repercussions in this year’s presidential race.

EUROZONE

GDP Forecasts

According to the forecasts published by the International Monetary Fund, Eurozone - considered as a whole - will see GDP declining by 7.5% in 2020, while a rebound of 4,7% has been estimated for the following year. Forecasts provided by FactSet are instead more optimistic: outlook for Eurozone real GDP is -5.2% in 2020 and, after a drop by 3.5% in the first quarter followed by dramatic fall by 10.0% in the second one, a rebound of Eurozone GDP is expected in the third quarter (+8.3%).

Before the global outbreak of the virus, growth in the euro area was projected to pick up from 1.2% in 2019 to 1.3% this year. However, the uncertainty related to these previsions is extremely high. Until now, there have been drastic measures taken to contain the virus and to enable healthcare systems to face it, such as quarantine and partial lockdowns. As a consequence, the impact on economic activity is severe and we are seeing its first results.

Italy is one of the countries which will suffer the most: IMF predicted a GDP contraction of 9.1%. Comparing this forecast with the other Eurozone states, it turns out that only Greece was estimated to be hit by a larger contraction (10%). In Italy all non-essential activities were halted on March 23rd. After that, the recovery has taken place very gradually: on May 4th macro-sectors of construction and manufacturing were restarted, while other non-essential activities reopened only on May 18th. Without considering indirect effects, the lockdown alone is estimated to cut 0.5% a week from annual GDP. In addition, indirect effects are several but the most worrisome is tourism (13.2% of Italy’s GDP), which is expected to be severely hit by travel restrictions during the summer period.

Moreover, looking at the countries outside Europe, only three present slumps worse than the one predicted for Italy: Lebanon (-12%), Venezuela (-15%) and Macao (-29,6%).

Concerning other EU countries, German economy is projected to drop by 7,0%, similar to France, for which forecast is -7.2% of its annual GDP. Even Spain will see a fall and, according to IFM previsions, it will be about 8.0%.

Import-Export

Regarding import and export activities of the EU, the European Commission has issued its previsions. In particular, they said that Eurozone export of goods and services will decline by 9.2%, for an amount of €285bn, while imports of goods and services will decrease by 8.8%, or €240bn. This projection is based on the belief of the Commission that global trade will reduce by 9.7%. However, the World Trade Organization has estimated a drop of world trade between 13% and 32% during this year, as a consequence of Covid-19 outbreak worldwide.

CENTRAL BANKS AND GOVERNMENTS’ REACTION

GOVERNMENTS’ RESPONSE

Countries are responding aggressively to the current crisis with a range of measures to contain the spread of the virus through restrictions on movement to essential purposes only, a ban on public gatherings, closure of schools, universities and non-essential businesses with just few exceptions. Strict safety measures have been introduced for industrial companies still operating. Policymakers in the advanced economies have made good use of their policy space and institutions, putting in place large monetary and fiscal expansions to blunt the impact of the crisis. Fiscal rules and limits are rightly being suspended to enable large-scale emergency support. In this section, we’re going to consider Europe’s main governments’ intervention.

Germany

The federal government adopted a supplementary budget of €156 billion which includes spending on healthcare equipment, hospital capacity, R&D (vaccine). In addition, it expanded access to short-term work: the employment agency pays the short-time work allowance as a partial replacement for the lost wages due to a temporary loss of work. This relieves the employer of the costs of employing workers and hence avoids dismissals. Furthermore, the government expanded childcare benefits for low-income parents and easier access to basic income support for the self-employed and €50 billion in grants to small business owners and self-employed severely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in addition to interest-free tax deferrals until year-end.

At the same time, through the newly created economic stabilization fund (WSF) and the public development bank KFW, the government is expanding the volume and access to public loan guarantees for firms of different sizes and credit insurers, some eligible for up to 100 percent guarantees, increasing the total volume by at least €757 billion (23 percent of GDP).

Italy

On March 17, the government adopted a €25 billion (1.4% of GDP) Cura Italia emergency package whose four pillars are:

Spain

The Council of Ministers has approved a Royal Decree-Law with the greatest mobilization of economic resources in the democratic history of Spain to face the economic impact of the coronavirus. It has been decided to mobilize close to 20% of the GDP, with measures to protect and support families, workers, the self-employed and companies.

The first block of measures of the Royal Decree-Law is aimed at older people, dependents and vulnerable families. It allocates €600 million to finance basic benefits for the corresponding social services of the autonomous communities and local authorities, with special attention to home care for the elderly and dependents. Also, the government guaranteed the right to housing for those with serious economic difficulties.

The second block of measures reinforces employment protection to prevent a temporary crisis such as the current one from having a permanent negative impact on the labor market. For this, the government has agreed that salaried workers can adapt or reduce their working hours, even up to 100%, to meet the needs for conciliation and care derived from this crisis. Regarding this sector, the government has also introduced entitlements of unemployment benefits for workers temporarily laid off under the Temporary Employment Adjustment Schemes (ERTE), with no requirement for prior minimum contribution or reduction of accumulated entitlement.

The third block of measures ensured the liquidity of companies so that they can remain operational and ensure that a liquidity problem does not become a solvency problem. For this reason, the creation of a line of public guarantees has been approved for a value of up to €100 billion, besides tax payment deferrals for small-medium enterprises and self-employed for six months.

France

The authorities announced an increase in the fiscal envelope devoted to addressing the crisis to €110 billion from an initial €45 billion, including an amending budget law introduced in March. A new amending budget law was introduced on April 16th, which adds to an existing package of bank loan guarantees and credit reinsurance schemes of €315 billion. The government increased spending on health supplies and boosted health insurance for the sick or their caregivers.

As other European countries have done, to guarantee liquidity support, the country has postponed social security and tax payments for companies and accelerated refund of tax credits. It has also given direct financial support for affected microenterprises, liberal professions, and independent workers and has postponed rent and utility payments for affected microenterprises and SMEs. Furthermore, it has granted additional allocation for equity investments or nationalizations of companies in difficulty.

As for the labor market, it supported wages of workers under the reduced-hour scheme and extended the expiring unemployment benefits until the end of the lockdown and guaranteed the preservation of rights and benefits under the disability and active solidarity income schemes.

ECB’ REACTION

ECB's reaction to the outbreak of COVID-19 is mainly guided by three objectives, all of which are considered necessary for the achievement of its price stability mandate.

The need to address risks of adverse macro-financial feedback loops

Financial conditions of the Euro area have tightened remarkably after the global outbreak of COVID- 19. In a few days, the pandemic was able to invert the previous easing in financial conditions, whose aim was to bring inflation up in the medium-term. Since this threatened to cause a dangerous macro-financial feedback loop, the ECB decided to intervene in order to avoid that what had started as a health crisis would transform into a full-blown financial crisis, with destabilizing price spirals and fire sales.

At first, market participants remained disappointed by the choice of ECB not to cut the rates, as the Fed and Bank of England did. However, Christine Lagarde said that a further cut in the deposit facility rate would have been unlikely to support sentiment and market functioning at a time when the profitability of banks was already expected to come under additional pressure due to the crisis. Hence, the ECB intervened with three complementary components. First, the temporary pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP), with a volume of €750 billion of private and public securities throughout the year. Second, targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), as well as a comprehensive set of collateral easing measures to ensure that banks remain reliable and continue lending to the real economy. Third, ECB offers banks liquidity over longer horizons at the deposit facility rate – that is a negative rate – without any further condition.

The need to safeguard the monetary policy stance

In response to the Coronavirus outbreak, the GDP-weighted government bond yield curve dislocated significantly (around 70 basis points higher than before the pandemic, with even German Bund yields up to around 20 basis points over the same period), thus leading to a tightening of the monetary policy stance. The announcement of PEPP by the ECB broke this dynamic and partially inverted the steepening of the curve. Also, the Governing Council decided to make bonds issued by all euro area sovereigns, including those issued by the Hellenic Republic, eligible for purchases under the PEPP. This was a way to ensure that the shock caused by coronavirus would not deepen the heterogeneity among European countries, that had become increasingly visible in recent times.

The need to support firms and banks

From the very beginning of the crisis, ECB knew that abundant liquidity support was needed in segments of financial and capital markets directly exposed to the negative consequences of the pandemic. Therefore, ECB decided to redirect a considerable fraction of the additional €120 billion purchase envelope under the APP, as well as of the PEPP, for eligible private sector bonds. These private sector purchases, including commercial paper, directly contribute to credit easing for non- financial corporates. This represents the core of ECB response: preserving viable bank lending conditions and acting as a lender of last resort to solvent banks. Together with this action, ECB also provides a reliable backstop for firms and households during these challenging times. There are two other features of the ECB package that reinforce the bank lending channel: first, longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which provide extraordinary liquidity to banks at favorable rates; second, the acceptance of a much broader set of assets as collateral, including loans of small size to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or even self-employed workers. This increases the liquidity of the asset side of banks’ balance sheets, and thereby provides further incentives to extend credit to the real economy, even during the current challenging period.

FED’S REACTION

Over the last month, the Federal Reserve has put in place an extensive package of facilities to tackle the economic and financial consequences of the current pandemic.

The first array of measures was announced on March 15th and was aimed at enhancing the liquidity of banks and the financial system. This intervention was triggered by several worrisome signals in the debt markets in the previous weeks. Firstly, there was a spike in interest rates in the repo market – used by investors to cover short-term cash needs – hinting that banks were moving away from market making. In the same days, authorities were worried by an abnormal simultaneous decrease in both bond and stock prices. This behavior was alarming as, usually, during crisis, investors move away from stocks (causing prices to fall) and retreat to safer assets, such as Treasuries (whose prices increase). This relationship underpins most hedging strategies. A concurrent fall in prices of both assets startled authorities as it signaled that investors were moving towards cash. Finally, significant differences in prices of on-the-run Treasuries and off-the-run Treasuries (similar to on-the-run Treasuries, except for the fact that are issued at slightly different times) emerged and became more and more remarked. In normal times, investors trade them as exchangeable assets: however, as they started to worry about the liquidity of the market, on-the-run Treasuries began to trade at much more favorable conditions.

The Federal Reserve’s response to tackle those anomalies has been massive and complex.

Firstly, the Fed announced a 100 bp cut in the target policy range of the Federal Funds rate to 0 to 0.25% (on top of the 50-bp reduction they had agreed upon earlier in March). Reduction in interest rates are expected to stimulate investments and consumer spending. However, several investors and politician questioned the effectiveness of such monetary policy under current circumstances. In particular, the critiques argued that, due to the uncertainty about the length of the lockdown and the absolute size of its impact on economic activity, lower rates are unlikely to boost investments and spending. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester also noted that, once the reduction was carried out, the Federal Reserve would have been left without any rate-cut ammunition for the times when this interest rate policy could have been more effective in stimulating demand.

Secondly, the Fed committed to increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $500 billion and its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion, reinvesting all proceeds of principal repayments on existing holdings of agency securities. The Treasury market is arguably the world most liquid market and its correct functioning is paramount not only for monetary policy transmission but also because these securities are at the basis of the cash management of the majority of the corporations. Agency-guaranteed MBS market plays a similar role to the former. In previous weeks, the rush for cash among investors had determined disorders in both markets, creating liquidity issues.

Furthermore, the Fed encouraged banks to use the discount window to meet credit demand by reducing the charge from 150 basis points to 25 basis points and increasing the term of discount window loans to 90 days. The flexibility of this facility was also enhanced as banks were allowed to prepay and renew this credit line on a daily basis. As a result, this facility became the cheapest source of funding for banks and even larger institutions, such as JPMorgan Chase, immediately borrowed from the discount window. The purpose of this maneuver was to provide banks with an alternative to selling assets in illiquid markets at fire sale prices.

Regulatory capital and liquidity buffers were also relaxed, and reserve requirements were eliminated. The Fed aimed at enhancing banks’ ability to support lending to households and businesses. While these initiatives would free up space in the banks’ balance sheet to increase lending, it seemed that banks were not willing to increase their credit risk exposure because of current business uncertainty and doubt about corporations’ creditworthiness.

One of the most remarkable decisions was to liberalize swap lines with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank by lowering the cost to the Overnight Index Swap Rate (OIS) plus 25 basis points and extending the maturity of swaps to 84 days in addition to the customary 1 week maturity. Swap lines allow central banks to access dollars in exchange for their local currency.

As the epidemic impacted the business activities of corporations worldwide, there was a surge in demand of USD, required – for example – to service debt payments. The rationale of this maneuvers was to ease pressure on dollar and enhance its liquidity globally, by allowing other central banks to intervene, in order to avoid that an excessive appreciation of the currency would negatively affect US exports.

In the following days, between March 17 and 18, the Fed expanded its previous intervention with a series of additional facilities:

The first facility was the so-called PMCCF (Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility). It is a special purpose vehicle designed to ensure large employer access to the credit needed to keep functioning and limit layoffs. The money lent by the Fed to the SPV will be used to make loans to investment grade corporations and buy corporate bonds to sustain their functioning through the crisis. The bridge financing will have a maturity up to four years and borrowers will be allowed to postpone the repayment of interest and principal for the first six months.

The second facility was strictly related to the PMCCF and was the SMCCF (Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility). This SPV will purchase U.S. investment grade corporate bonds with a maturity of five years or less and bond ETFs (whose discussed inclusion was determined by the products’ widespread use among fund managers) in the secondary market. Even though this facility will not directly provide corporations with new credit, it was supposed to reassure banks about the availability of a strong secondary market for corporate debt, thus enhancing their willingness to lend to businesses.

In the same occasion, the Fed also revitalized a facility dating back to the financing crisis of 2008, the TALF (Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility). This program was aimed at supporting consumer credit lending and, in practice, the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS) collateralized by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA).

On March 27, President Trump signed the CARES Act into law – a $2tn coronavirus economic stimulus bill. The act includes $454 billion for Treasury to provide support to Fed programs for businesses, states and municipalities. This commitment by the Treasury will be used as the first-loss buffer to provide up to more than $4tn of loans, loan guarantees, and other investments to provide assistance to companies and liquidity to the financial system. Indeed, Fed Chair Jerome Powell claimed that “Effectively one dollar of loss absorption of backstop from Treasury is enough to support $10 worth of loans”.

On March 31, the Fed took another initiative to meet the surge in global demand of dollars, setting up a temporary facility for foreign and international monetary authorities (FIMA). Central banks and international foreign authorities will be able to “exchange their US Treasury securities held with the Federal Reserve for US dollars”, as claimed in the Fed statement. The purpose of this additional facility was to prevent institutions from satisfying their need of dollars through sales of securities in open markets, while enhancing the functioning of the Treasury market.

On April 2, the Fed also announced a temporary revision to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio. Banks may now exclude their holdings of Treasuries and cash reserves from their calculation of the ratio. This will increase the regulatory ratio, creating room for further lending activity, and ensure that banks will be able to take the cash reserves pushed by the Fed in the financial system. On top of that, the maneuver is expected to enhance the liquidity of the Treasury market, eliminating previous constraints to banks.

On April 6, the Fed announced a new facility to help small businesses to obtain the funding needed to survive during the epidemic. The SBA program, which is the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) subsection of the CARES Act, will allow banks to sell loan through their PPP facility. The PPP is a $350bn fund aimed at helping small businesses and was announced as part of the $2tn fiscal stimulus package passed by Congress in March. Without the implementation of such program, banks would have been forced to hold the loans up to maturity and this would have remarkably constrained their lending capacity. This facility will free up space in banks’ balance sheets to boost their lending activity. Despite this, balance sheet constraint was not the only factor impeding banks to ramp-up the program quickly: the supply of liquidity is unlikely to be sufficient to satisfy the demand and operational constraints are slowing down the ability of banks to address the needs of all customers. Besides, the clear risk of this facility is that, if banks act as underwriters (and consequently have “no skin in the game”), it creates incentives to overlook the effective creditworthiness of borrowers. To limit moral hazard, banks will be subject to an ex-post examination by authorities.

On April 9, the Fed unveiled another action among its remedies to fight the epidemic by announcing loan facilities worth $2.3tn to deliver credit to small businesses and municipalities. In detail, the program will involve the purchase of short-term debt (up to two years) directly from U.S. states - counties with a population of at least 2m people and cities with at least 1m residents - up to $500 billion, to help them in meeting the increased demand of services. It also expanded measures introduced last month to back corporate debt markets. The Fed also said it would create a separate lending programme for “Main Street” — which was also authorized in the stimulus legislation — through which it will buy up to $600bn in loans with a backing of $75bn from the Treasury department. The program aims at giving relief to companies that are too large to qualify for the SBA program and not large enough to access corporate debt markets. The Fed announced significant measures also with regards to corporate debt markets. In particular, credit backstop will be provided to the so-call fallen-angels, i.e. companies whose ratings has been downgraded from investment grade to high yield after March 15, and purchases will be extended to non-investment grade ETFs. Finally, the previously announced TALF will accept also highest-rated tranches of existing commercial mortgage-backed securities and newly issued collateralized loan obligations.

The Federal Reserve’s intervention has been massive and aimed at providing businesses with the resources required to go through the epidemic, limiting layoffs as much as possible, and ensuring the smooth functioning of financial markets. In other words, the Fed resorted to drastic measures to prevent the economic crisis from turning into a financial one. To this end, it has definitively gone beyond traditional monetary policy and embraced a wide array of unconventional monetary policy tools.

Countries are responding aggressively to the current crisis with a range of measures to contain the spread of the virus through restrictions on movement to essential purposes only, a ban on public gatherings, closure of schools, universities and non-essential businesses with just few exceptions. Strict safety measures have been introduced for industrial companies still operating. Policymakers in the advanced economies have made good use of their policy space and institutions, putting in place large monetary and fiscal expansions to blunt the impact of the crisis. Fiscal rules and limits are rightly being suspended to enable large-scale emergency support. In this section, we’re going to consider Europe’s main governments’ intervention.

Germany

The federal government adopted a supplementary budget of €156 billion which includes spending on healthcare equipment, hospital capacity, R&D (vaccine). In addition, it expanded access to short-term work: the employment agency pays the short-time work allowance as a partial replacement for the lost wages due to a temporary loss of work. This relieves the employer of the costs of employing workers and hence avoids dismissals. Furthermore, the government expanded childcare benefits for low-income parents and easier access to basic income support for the self-employed and €50 billion in grants to small business owners and self-employed severely affected by the COVID-19 outbreak in addition to interest-free tax deferrals until year-end.

At the same time, through the newly created economic stabilization fund (WSF) and the public development bank KFW, the government is expanding the volume and access to public loan guarantees for firms of different sizes and credit insurers, some eligible for up to 100 percent guarantees, increasing the total volume by at least €757 billion (23 percent of GDP).

Italy

On March 17, the government adopted a €25 billion (1.4% of GDP) Cura Italia emergency package whose four pillars are:

- Funds to strengthen the Italian health care system and civil protection;

- Measures to preserve jobs and support income of laid-off workers and self-employed;

- Other measures to support businesses, including tax deferrals and postponement of utility bill payments in most affected municipalities;

- Pumping a huge amount of liquidity to help businesses and households and measures to support credit supply.

Spain

The Council of Ministers has approved a Royal Decree-Law with the greatest mobilization of economic resources in the democratic history of Spain to face the economic impact of the coronavirus. It has been decided to mobilize close to 20% of the GDP, with measures to protect and support families, workers, the self-employed and companies.

The first block of measures of the Royal Decree-Law is aimed at older people, dependents and vulnerable families. It allocates €600 million to finance basic benefits for the corresponding social services of the autonomous communities and local authorities, with special attention to home care for the elderly and dependents. Also, the government guaranteed the right to housing for those with serious economic difficulties.

The second block of measures reinforces employment protection to prevent a temporary crisis such as the current one from having a permanent negative impact on the labor market. For this, the government has agreed that salaried workers can adapt or reduce their working hours, even up to 100%, to meet the needs for conciliation and care derived from this crisis. Regarding this sector, the government has also introduced entitlements of unemployment benefits for workers temporarily laid off under the Temporary Employment Adjustment Schemes (ERTE), with no requirement for prior minimum contribution or reduction of accumulated entitlement.

The third block of measures ensured the liquidity of companies so that they can remain operational and ensure that a liquidity problem does not become a solvency problem. For this reason, the creation of a line of public guarantees has been approved for a value of up to €100 billion, besides tax payment deferrals for small-medium enterprises and self-employed for six months.

France

The authorities announced an increase in the fiscal envelope devoted to addressing the crisis to €110 billion from an initial €45 billion, including an amending budget law introduced in March. A new amending budget law was introduced on April 16th, which adds to an existing package of bank loan guarantees and credit reinsurance schemes of €315 billion. The government increased spending on health supplies and boosted health insurance for the sick or their caregivers.

As other European countries have done, to guarantee liquidity support, the country has postponed social security and tax payments for companies and accelerated refund of tax credits. It has also given direct financial support for affected microenterprises, liberal professions, and independent workers and has postponed rent and utility payments for affected microenterprises and SMEs. Furthermore, it has granted additional allocation for equity investments or nationalizations of companies in difficulty.

As for the labor market, it supported wages of workers under the reduced-hour scheme and extended the expiring unemployment benefits until the end of the lockdown and guaranteed the preservation of rights and benefits under the disability and active solidarity income schemes.

ECB’ REACTION

ECB's reaction to the outbreak of COVID-19 is mainly guided by three objectives, all of which are considered necessary for the achievement of its price stability mandate.

The need to address risks of adverse macro-financial feedback loops

Financial conditions of the Euro area have tightened remarkably after the global outbreak of COVID- 19. In a few days, the pandemic was able to invert the previous easing in financial conditions, whose aim was to bring inflation up in the medium-term. Since this threatened to cause a dangerous macro-financial feedback loop, the ECB decided to intervene in order to avoid that what had started as a health crisis would transform into a full-blown financial crisis, with destabilizing price spirals and fire sales.

At first, market participants remained disappointed by the choice of ECB not to cut the rates, as the Fed and Bank of England did. However, Christine Lagarde said that a further cut in the deposit facility rate would have been unlikely to support sentiment and market functioning at a time when the profitability of banks was already expected to come under additional pressure due to the crisis. Hence, the ECB intervened with three complementary components. First, the temporary pandemic emergency purchase program (PEPP), with a volume of €750 billion of private and public securities throughout the year. Second, targeted longer-term refinancing operations (TLTROs), as well as a comprehensive set of collateral easing measures to ensure that banks remain reliable and continue lending to the real economy. Third, ECB offers banks liquidity over longer horizons at the deposit facility rate – that is a negative rate – without any further condition.

The need to safeguard the monetary policy stance

In response to the Coronavirus outbreak, the GDP-weighted government bond yield curve dislocated significantly (around 70 basis points higher than before the pandemic, with even German Bund yields up to around 20 basis points over the same period), thus leading to a tightening of the monetary policy stance. The announcement of PEPP by the ECB broke this dynamic and partially inverted the steepening of the curve. Also, the Governing Council decided to make bonds issued by all euro area sovereigns, including those issued by the Hellenic Republic, eligible for purchases under the PEPP. This was a way to ensure that the shock caused by coronavirus would not deepen the heterogeneity among European countries, that had become increasingly visible in recent times.

The need to support firms and banks

From the very beginning of the crisis, ECB knew that abundant liquidity support was needed in segments of financial and capital markets directly exposed to the negative consequences of the pandemic. Therefore, ECB decided to redirect a considerable fraction of the additional €120 billion purchase envelope under the APP, as well as of the PEPP, for eligible private sector bonds. These private sector purchases, including commercial paper, directly contribute to credit easing for non- financial corporates. This represents the core of ECB response: preserving viable bank lending conditions and acting as a lender of last resort to solvent banks. Together with this action, ECB also provides a reliable backstop for firms and households during these challenging times. There are two other features of the ECB package that reinforce the bank lending channel: first, longer-term refinancing operations (LTROs), which provide extraordinary liquidity to banks at favorable rates; second, the acceptance of a much broader set of assets as collateral, including loans of small size to small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) or even self-employed workers. This increases the liquidity of the asset side of banks’ balance sheets, and thereby provides further incentives to extend credit to the real economy, even during the current challenging period.

FED’S REACTION

Over the last month, the Federal Reserve has put in place an extensive package of facilities to tackle the economic and financial consequences of the current pandemic.

The first array of measures was announced on March 15th and was aimed at enhancing the liquidity of banks and the financial system. This intervention was triggered by several worrisome signals in the debt markets in the previous weeks. Firstly, there was a spike in interest rates in the repo market – used by investors to cover short-term cash needs – hinting that banks were moving away from market making. In the same days, authorities were worried by an abnormal simultaneous decrease in both bond and stock prices. This behavior was alarming as, usually, during crisis, investors move away from stocks (causing prices to fall) and retreat to safer assets, such as Treasuries (whose prices increase). This relationship underpins most hedging strategies. A concurrent fall in prices of both assets startled authorities as it signaled that investors were moving towards cash. Finally, significant differences in prices of on-the-run Treasuries and off-the-run Treasuries (similar to on-the-run Treasuries, except for the fact that are issued at slightly different times) emerged and became more and more remarked. In normal times, investors trade them as exchangeable assets: however, as they started to worry about the liquidity of the market, on-the-run Treasuries began to trade at much more favorable conditions.

The Federal Reserve’s response to tackle those anomalies has been massive and complex.

Firstly, the Fed announced a 100 bp cut in the target policy range of the Federal Funds rate to 0 to 0.25% (on top of the 50-bp reduction they had agreed upon earlier in March). Reduction in interest rates are expected to stimulate investments and consumer spending. However, several investors and politician questioned the effectiveness of such monetary policy under current circumstances. In particular, the critiques argued that, due to the uncertainty about the length of the lockdown and the absolute size of its impact on economic activity, lower rates are unlikely to boost investments and spending. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester also noted that, once the reduction was carried out, the Federal Reserve would have been left without any rate-cut ammunition for the times when this interest rate policy could have been more effective in stimulating demand.

Secondly, the Fed committed to increase its holdings of Treasury securities by at least $500 billion and its holdings of agency mortgage-backed securities by at least $200 billion, reinvesting all proceeds of principal repayments on existing holdings of agency securities. The Treasury market is arguably the world most liquid market and its correct functioning is paramount not only for monetary policy transmission but also because these securities are at the basis of the cash management of the majority of the corporations. Agency-guaranteed MBS market plays a similar role to the former. In previous weeks, the rush for cash among investors had determined disorders in both markets, creating liquidity issues.

Furthermore, the Fed encouraged banks to use the discount window to meet credit demand by reducing the charge from 150 basis points to 25 basis points and increasing the term of discount window loans to 90 days. The flexibility of this facility was also enhanced as banks were allowed to prepay and renew this credit line on a daily basis. As a result, this facility became the cheapest source of funding for banks and even larger institutions, such as JPMorgan Chase, immediately borrowed from the discount window. The purpose of this maneuver was to provide banks with an alternative to selling assets in illiquid markets at fire sale prices.

Regulatory capital and liquidity buffers were also relaxed, and reserve requirements were eliminated. The Fed aimed at enhancing banks’ ability to support lending to households and businesses. While these initiatives would free up space in the banks’ balance sheet to increase lending, it seemed that banks were not willing to increase their credit risk exposure because of current business uncertainty and doubt about corporations’ creditworthiness.

One of the most remarkable decisions was to liberalize swap lines with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the Bank of Japan and the European Central Bank and the Swiss National Bank by lowering the cost to the Overnight Index Swap Rate (OIS) plus 25 basis points and extending the maturity of swaps to 84 days in addition to the customary 1 week maturity. Swap lines allow central banks to access dollars in exchange for their local currency.

As the epidemic impacted the business activities of corporations worldwide, there was a surge in demand of USD, required – for example – to service debt payments. The rationale of this maneuvers was to ease pressure on dollar and enhance its liquidity globally, by allowing other central banks to intervene, in order to avoid that an excessive appreciation of the currency would negatively affect US exports.

In the following days, between March 17 and 18, the Fed expanded its previous intervention with a series of additional facilities:

- Establishment of a Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF) by standing ready to purchase unsecured and asset-backed commercial paper rate A1/P1 (i.e. highly rated) directly from eligible companies. The Treasury will provide $10bn of credit protection to the Federal Reserve from the Exchange Stabilization Fund to guarantee the credit risk in this facility. The commercial paper market represents a paramount source of funding for large corporations to cover short-term needs. In the previous weeks, the market seems to freeze because of the joint effect of a rush to cash and a pull back by money market funds (one of the biggest players in this market) that led to a spike in borrowing costs. The purpose of the Fed’s initiative was to encourage investors to come back to the market and ensure that businesses had the financing required to weather through troubled times.

- Establishment of a Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) that will allow primary dealers to support the smooth functioning of markets. The PDCF offer overnight and term funding up to 90 days at the discount rate of 25 basis points. Credit to primary dealers may be collateralized by a broad range of investment grade debt securities including commercial paper and municipal bonds and a broad range of equity securities.

- Establishment of a Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (MMLF) designed to "support the flow of credit to households and businesses [...] enhance the liquidity and functioning of the financial markets and to support the economy.". The Boston Fed will lend to eligible money market mutual funds (MMMFs) secured by high-quality assets including high-quality state and municipal bonds to assist them in meeting demands for redemptions. The Treasury will provide $10 billion in credit protection for this facility from the Exchange Stabilization Fund.

The first facility was the so-called PMCCF (Primary Market Corporate Credit Facility). It is a special purpose vehicle designed to ensure large employer access to the credit needed to keep functioning and limit layoffs. The money lent by the Fed to the SPV will be used to make loans to investment grade corporations and buy corporate bonds to sustain their functioning through the crisis. The bridge financing will have a maturity up to four years and borrowers will be allowed to postpone the repayment of interest and principal for the first six months.

The second facility was strictly related to the PMCCF and was the SMCCF (Secondary Market Corporate Credit Facility). This SPV will purchase U.S. investment grade corporate bonds with a maturity of five years or less and bond ETFs (whose discussed inclusion was determined by the products’ widespread use among fund managers) in the secondary market. Even though this facility will not directly provide corporations with new credit, it was supposed to reassure banks about the availability of a strong secondary market for corporate debt, thus enhancing their willingness to lend to businesses.

In the same occasion, the Fed also revitalized a facility dating back to the financing crisis of 2008, the TALF (Term Asset-Backed Securities Loan Facility). This program was aimed at supporting consumer credit lending and, in practice, the issuance of asset-backed securities (ABS) collateralized by student loans, auto loans, credit card loans, and loans guaranteed by the Small Business Administration (SBA).

On March 27, President Trump signed the CARES Act into law – a $2tn coronavirus economic stimulus bill. The act includes $454 billion for Treasury to provide support to Fed programs for businesses, states and municipalities. This commitment by the Treasury will be used as the first-loss buffer to provide up to more than $4tn of loans, loan guarantees, and other investments to provide assistance to companies and liquidity to the financial system. Indeed, Fed Chair Jerome Powell claimed that “Effectively one dollar of loss absorption of backstop from Treasury is enough to support $10 worth of loans”.

On March 31, the Fed took another initiative to meet the surge in global demand of dollars, setting up a temporary facility for foreign and international monetary authorities (FIMA). Central banks and international foreign authorities will be able to “exchange their US Treasury securities held with the Federal Reserve for US dollars”, as claimed in the Fed statement. The purpose of this additional facility was to prevent institutions from satisfying their need of dollars through sales of securities in open markets, while enhancing the functioning of the Treasury market.

On April 2, the Fed also announced a temporary revision to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio. Banks may now exclude their holdings of Treasuries and cash reserves from their calculation of the ratio. This will increase the regulatory ratio, creating room for further lending activity, and ensure that banks will be able to take the cash reserves pushed by the Fed in the financial system. On top of that, the maneuver is expected to enhance the liquidity of the Treasury market, eliminating previous constraints to banks.

On April 6, the Fed announced a new facility to help small businesses to obtain the funding needed to survive during the epidemic. The SBA program, which is the Payroll Protection Program (PPP) subsection of the CARES Act, will allow banks to sell loan through their PPP facility. The PPP is a $350bn fund aimed at helping small businesses and was announced as part of the $2tn fiscal stimulus package passed by Congress in March. Without the implementation of such program, banks would have been forced to hold the loans up to maturity and this would have remarkably constrained their lending capacity. This facility will free up space in banks’ balance sheets to boost their lending activity. Despite this, balance sheet constraint was not the only factor impeding banks to ramp-up the program quickly: the supply of liquidity is unlikely to be sufficient to satisfy the demand and operational constraints are slowing down the ability of banks to address the needs of all customers. Besides, the clear risk of this facility is that, if banks act as underwriters (and consequently have “no skin in the game”), it creates incentives to overlook the effective creditworthiness of borrowers. To limit moral hazard, banks will be subject to an ex-post examination by authorities.

On April 9, the Fed unveiled another action among its remedies to fight the epidemic by announcing loan facilities worth $2.3tn to deliver credit to small businesses and municipalities. In detail, the program will involve the purchase of short-term debt (up to two years) directly from U.S. states - counties with a population of at least 2m people and cities with at least 1m residents - up to $500 billion, to help them in meeting the increased demand of services. It also expanded measures introduced last month to back corporate debt markets. The Fed also said it would create a separate lending programme for “Main Street” — which was also authorized in the stimulus legislation — through which it will buy up to $600bn in loans with a backing of $75bn from the Treasury department. The program aims at giving relief to companies that are too large to qualify for the SBA program and not large enough to access corporate debt markets. The Fed announced significant measures also with regards to corporate debt markets. In particular, credit backstop will be provided to the so-call fallen-angels, i.e. companies whose ratings has been downgraded from investment grade to high yield after March 15, and purchases will be extended to non-investment grade ETFs. Finally, the previously announced TALF will accept also highest-rated tranches of existing commercial mortgage-backed securities and newly issued collateralized loan obligations.

The Federal Reserve’s intervention has been massive and aimed at providing businesses with the resources required to go through the epidemic, limiting layoffs as much as possible, and ensuring the smooth functioning of financial markets. In other words, the Fed resorted to drastic measures to prevent the economic crisis from turning into a financial one. To this end, it has definitively gone beyond traditional monetary policy and embraced a wide array of unconventional monetary policy tools.

KEY INDICATORS

As we progress through this crisis, it is crucial to understand which indicators we should turn to in order to monitor the state of the recovery. In this section, we take into consideration what we believe to be the best proxies for the strength of the global economy.

Unemployment rate and jobless claims

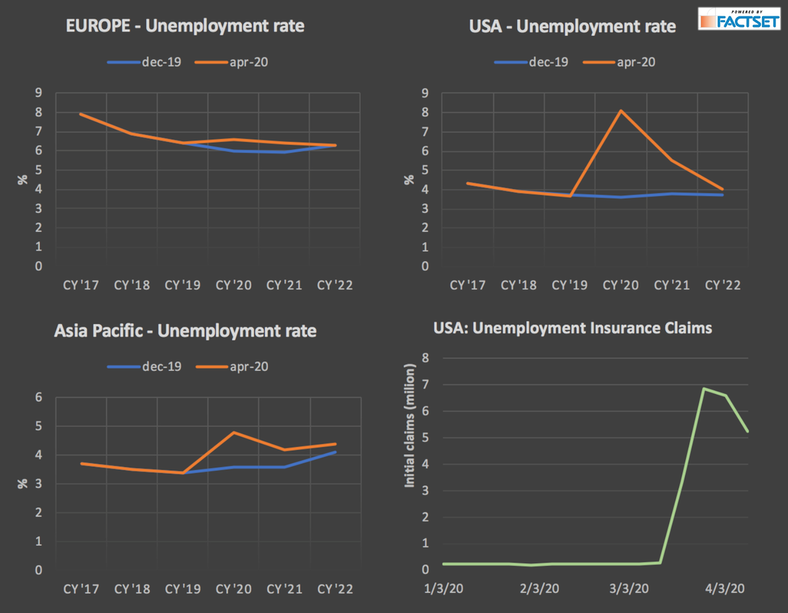

Confronting predictions on the rate of unemployment recorded at the end of 2019 with the ones of April 2020, the gap is evident.

In December, both Europe and the US were predicting a reduction in their unemployment rate, while the indicator was going to rise by 0.2% in Asia Pacific. However, the situation has drastically changed nowadays. Among the three areas, Europe is going to suffer the least, with a light spread of 0.6% among the two forecasts. The US stand as the most afflicted country, as analysts are convinced that the rate will go up to 8% this year. Compared to the 3.6% predicted three months ago, this is a very negative sign for the American labor market. Another sign of this suffering is the tremendous rise in jobless claims recorded few weeks ago: the total amount of initial claims reached a peak of 7 million, compared to an average of 250,000 in January and February 2020.

Unemployment rate and jobless claims

Confronting predictions on the rate of unemployment recorded at the end of 2019 with the ones of April 2020, the gap is evident.

In December, both Europe and the US were predicting a reduction in their unemployment rate, while the indicator was going to rise by 0.2% in Asia Pacific. However, the situation has drastically changed nowadays. Among the three areas, Europe is going to suffer the least, with a light spread of 0.6% among the two forecasts. The US stand as the most afflicted country, as analysts are convinced that the rate will go up to 8% this year. Compared to the 3.6% predicted three months ago, this is a very negative sign for the American labor market. Another sign of this suffering is the tremendous rise in jobless claims recorded few weeks ago: the total amount of initial claims reached a peak of 7 million, compared to an average of 250,000 in January and February 2020.

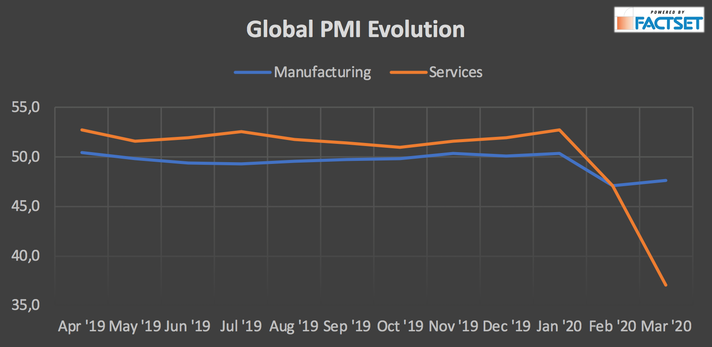

Manufacturing and Services activity

Activity in the manufacturing and services sectors is a good proxy for the health of an economy. When these sectors experience an expansion, it is because of a greater demand for products and services – which in turn influences positively GDP, and moreover favors employment levels.

The health of these sectors was analyzed using the Purchasing Managers' Index (PMI). This is an indicator derived from surveying companies about their view on future market conditions. When the index experiences values below 50, it signals a deterioration in future expected conditions.

As it can be observed from the aggregated data, while both sectors are expecting a contraction, this is going to hit services in a much harder way: the value of the index for services in the month of April was 37, the lowest value on record. The situation appears to be even worse when analyzing the data for the European Union, where the average services PMI has a value of 26,4 – dipping to 17,4 for the country expecting the largest decline (Italy).

Another proxy to monitor the evolution of activity in the manufacturing sector is the total industrial production. Beware, however, that this indicator is published with a lag and has to be therefore analyzed together with other measures such as PMI so as to get a more complete picture of the situation.

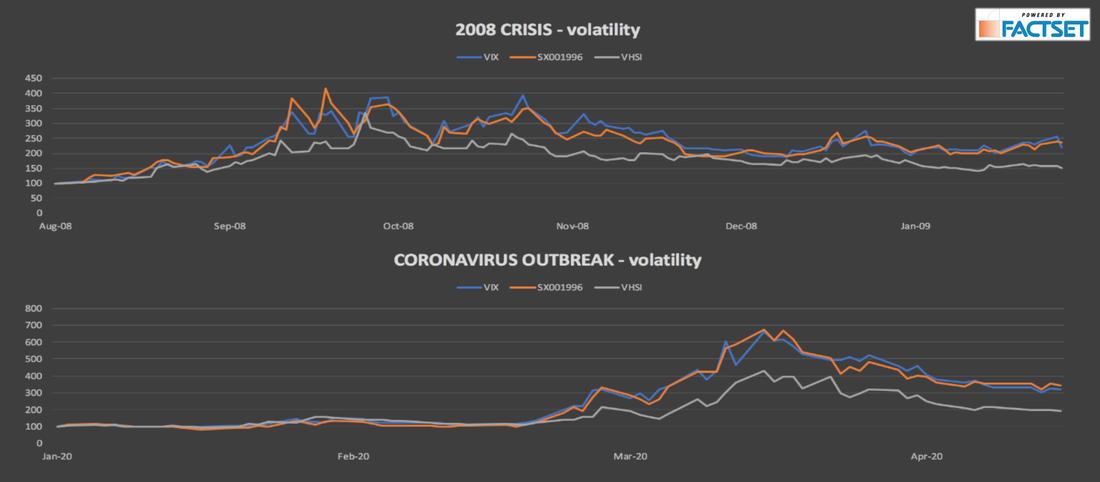

Market Volatility

As the novel Coronavirus spread outside of China and it became increasingly apparent that the crisis it would bring was going to be more serious than previously anticipated, the market became increasingly volatile.

The week of February 24th, for instance, the Dow Jones experienced its largest one-day drop since the 2008 financial crisis – only to record its largest one-day gain since 2009 the following week.

The fear, combined with the stimuli provided by central banks worldwide, contributed to unprecedented levels of volatility, and we were able to see the VIX, VSTOXX and the HIS volatility indices surpass the peaks they had reached during the crisis of 2008.

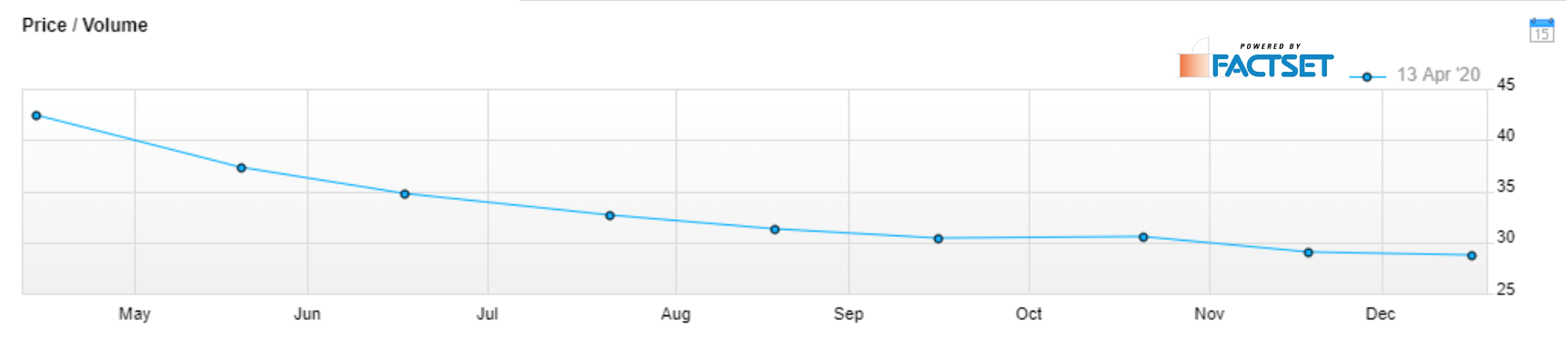

However, it would appear that markets expect volatility to decrease gradually, as the graph for VIX futures displays a downward trend. It has to be considered, however, that for more distant maturities the volume of futures is not as high and thus the price might not be very reliable.

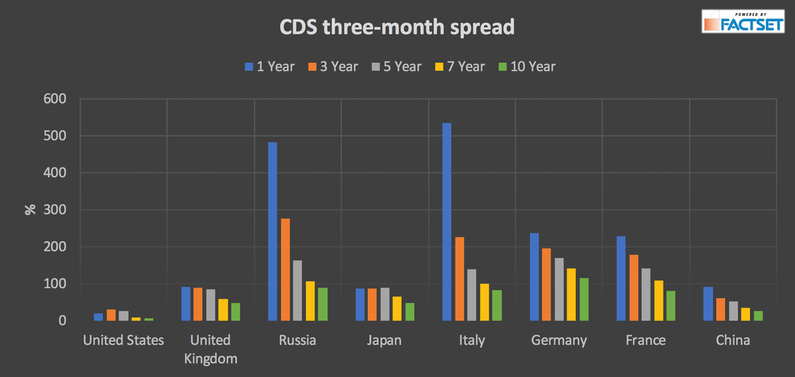

CDS Spread Changes

Reflecting the cost to insure against the default of an entity, we can use the spreads on Credit Default Swaps to measure the effect this crisis is having on the creditworthiness of several countries.

Comparing the CDS premiums prevailing in the market 3 months ago to the ones we can observe today, we find increases across the board (even if the variability of this change is considerable). The most notable wideners are Italy, Russia, Germany and France – which recorded an average increase in CDS spreads of 370% for the one-year maturity. On the other end of the spectrum, the US and Canada – with a markedly lower increase of only 20 percentage points.

As one might expect, premia for longer maturities did not increase quite as much, as average the credit risk of the countries in the unpredictable near future with their credit risk in more standard conditions.

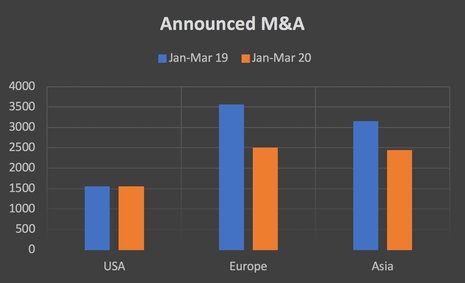

M&A

Predictably, M&A activity has experienced a significant decline. As companies continue to shift their focus away from external growth and towards weathering the current storm, we can expect the number of announced deals to remain fairly low.

So far, the market has recorded a sharp year-on-year drop in deals announced in the first quarter of 2020 compared with the previous year. The more drastic figures come from Europe (down almost 30%), closely followed by Asia (down about 23%). The American market seems to be the healthiest to date – recoding a neutral trend (+0.06%).

|

However, it has to be considered that USA was one of the latest countries to be afflicted by the novel coronavirus, and it could be just a matter of time before the above-mentioned trend appears there as well. Indeed, the US has been recording the worst performance since the beginning of April, while Far East and central Asia seem to be starting their recover from the bad performances of the previous months.

As the crisis progresses, we can expect to observe a wave of M&A deals concerning distressed companies and driven by the need of consolidation. When the majority of deals will instead involve healthy companies looking for avenues for growth, we will know that the market is recovering. |

|

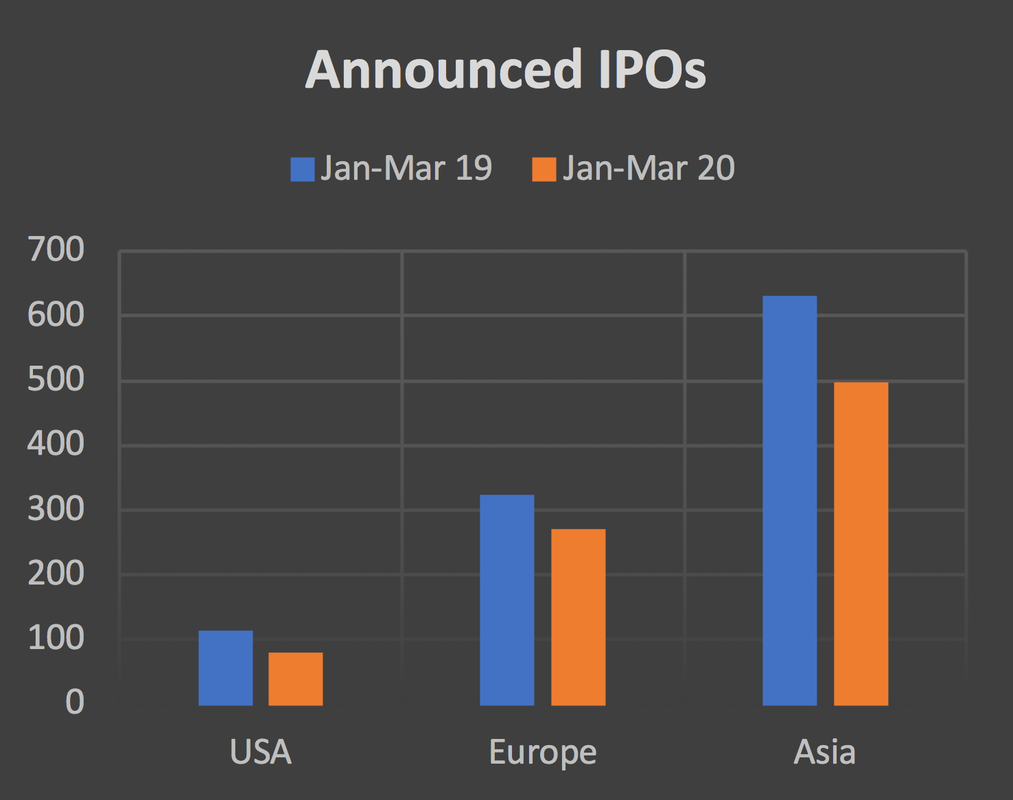

IPOs As the level of uncertainty in the market has increased dramatically in the last few months, also the number of announced IPOs has decreased. Until conditions stabilize, in fact, institutional investors can be expected to limit their exposures to companies they have an especially good knowledge of and show less appetite for newly listed firms (consequently making it harder for the latter to raise funds on favourable terms). The year-on-year change for the number of offerings announced in the period between January and March records a staggering 30% decline for the United States and a drop of roughly 16% and 21% respectively for Europe and Asia. |

EPS and Sales Outlook

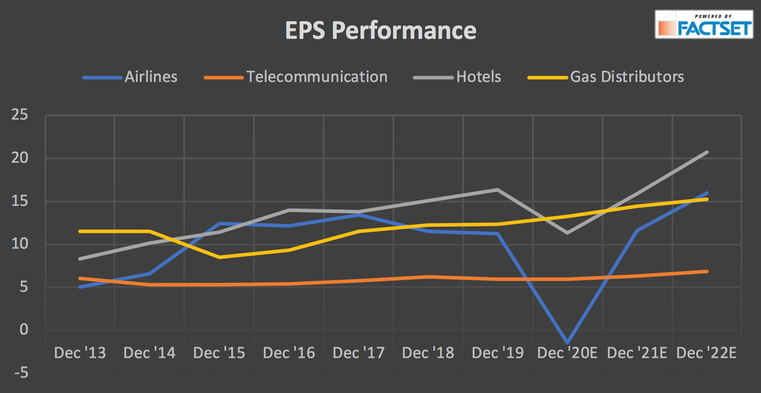

Needless to say, some industries are in a much better position than others to face the COVID crisis. In particular, Telecommunication and Gas Distribution are set to be some of the least affected – on the other hand we have the Airline and Hotel industries.

This is reflected in their EPS forecasts: while the crisis is not expected to make a dent in the EPS of the former two industries, hotels are likely to experience a 30% drop in EPS and airlines are expected in aggregate to post losses in 2020. As the crisis progresses, it will be crucial to pay attention to the “air passenger demand” in order to assess the state of both airlines and hotels (this, in fact, is an indicator which roughly proxies for the level of tourism and business travel – which have a direct impact on the profitability of hotels as well).

A similar trend can be seen looking at the sales per share performance. More specifically, sales of airlines and hotels are expected to decrease by 19% and 12% respectively, while the least affected industries are predicted not to experience any positive or negative change.

Novel Coronavirus Cases

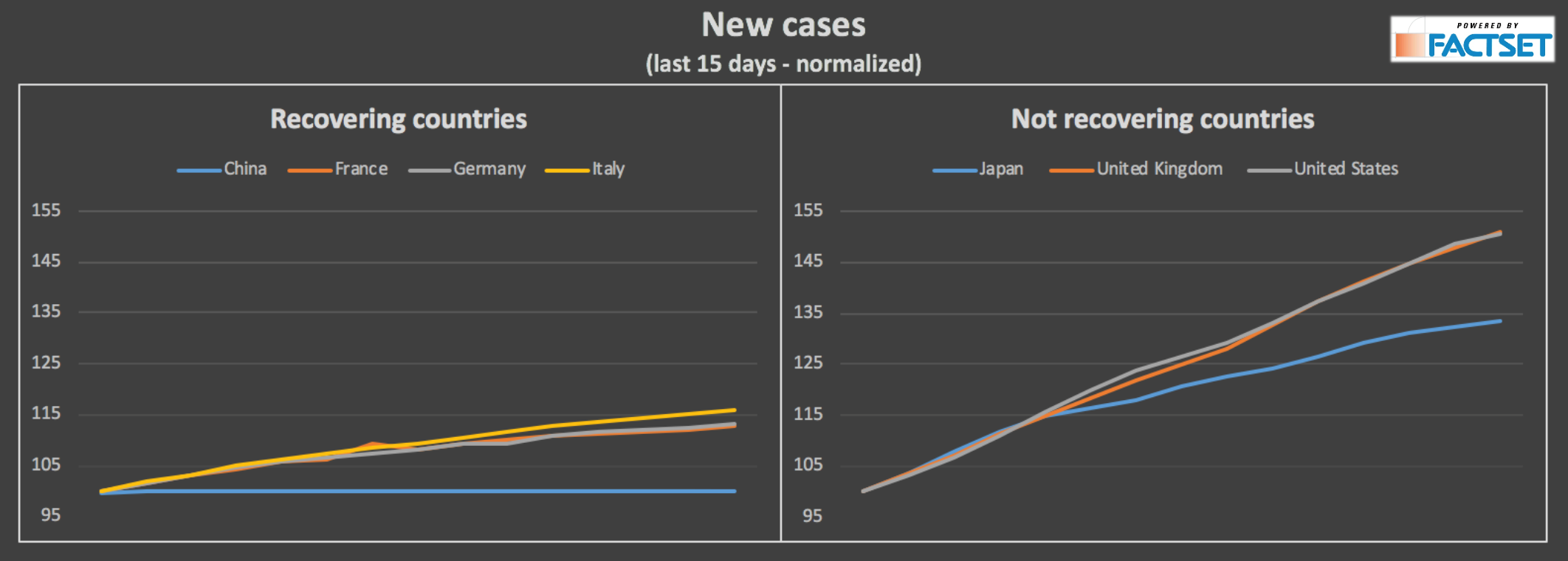

Lastly, the indicator that will more than any other shine a light on where we find ourselves in this crisis is of course the number of new cases of COVID-19 registered around the globe. As we know, the disease originated in China in January and hit Europe at the end of February and the US few weeks later. As we can observe in the two charts, those countries who decided to postpone the lockdown to save their economy, for instance the US and the UK, have not entered “phase 2” yet, as the trend over the last 15 days doesn’t seem to flatten. The similar situation recorded in Japan is instead due to the error of putting an end to the lockdown too early. We will understand within a few weeks whether the announcement of the start of phase 2 by those nations who seem to be recovering (left chart) will have been the best choice to relaunch the economy or a terrible mistake we are going to pay for in the future.

While forecasting what’s to come may seem like a hopeless task at the moment, we hope this article was able to help guide your future decisions by providing a clear understanding of what has happened in the global economy up to now, what are the most up to date estimates and which indicators are to be observed closely in order to monitor the state of the recovery.

Beatrice Bianchi, Edoardo D’Aprile, Gloria Urbini Capanni, Lorenzo Masserini, Luigi Marchese, Alessandro Marengo, Pietro Maraldi, Tamás Lakos

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.