The unraveling of the 167 years old Swiss bank has been one of the most interesting events on the market in recent times. But what are the reasons that led to this collapse? With a history packed with scandals, and profitability declining over the past months, uncertainty about the solidity of the banking system has hit particularly hard the Swiss lender, whose rescue by the historic rival UBS has been unprecedented in its modalities, and raises numerous questions about what is the role of regulators today in the banking industry.

Overview

Credit Suisse's soon-to-be takeover by UBS is all over the major headlines, and any reader that has been following the news in the past months is not really surprised by the announcement.

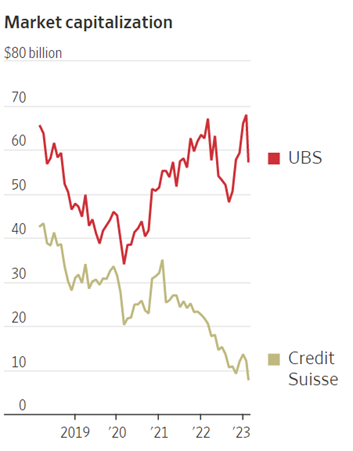

The situation Credit Suisse found itself in leading up to this was very dire. Due to an extreme loss in confidence in the bank’s ability to generate cash flows, its bond and stock prices fell dramatically, and consumer outflows peaked at $10 billion daily, as cited by the Wall Street Journal. As of Monday, March 22, when markets opened after the announcement of the deal, Credit Suisse equities were down by over 50% (reaching approximately the price UBS announced it would pay in its own stocks), while UBS experienced some growth after a previous drop of 14%. The deal was facilitated by the heavy intervention of the Swiss government, after an initial liquidity backstop offered by the Swiss National Bank, amounting to SFr50bn, or the equivalent of $54bn, was ineffective in restoring investor confidence.

But how did the Swiss bank get to this last resort? Crooks, money launderers and corrupt politicians being loyal clients of the bank, together with the many questionable financial practices that the institution has taken part in in the last decades, have led Credit Suisse to operate on very shaky ground that is now on the verge of collapse after the severe slump in its shares and bonds that took place on Wednesday, March 15th.

A long history of controversies

One of Credit Suisse’s first public scandals took place in 1986, when Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos were found to be clients of the bank. The Philippine dictator and his wife, indeed, had bank accounts under fake names where they stored part of the $5bn-$10bn they stole from the country during Ferdinand Marcos’ three terms of office. In 1995 a court ordered banks, including Credit Suisse, to return $500m of stolen funds to the Philippines, but the Swiss institution didn’t learn from its mistakes. As a matter of fact, during the 1990s, the bank accepted $214m worth of funds linked to corruption by Sani Abacha, Nigerian military dictator who stole millions of dollars from his own country and people. When charged by the Swiss Federal Bank, Credit Suisse stated that the political exposure of the client wasn’t known to the bankers who dealt with the operations. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, the promised improvement in the institution’s monitoring procedures hasn’t happened, with the Swiss bank being linked to the Japanese Yakuza and a Bulgarian drug ring that led it to face a criminal trial, the first one in history against a Swiss bank.

In addition to weak monitoring practices, the bank has been involved in many illegal financial conducts, among which we find tax evasions in numerous countries (Credit Suisse has been found guilty of this in Germany, the United States and Italy) and the Mozambique tuna bonds case, a loan bribery scandal that subsequently pushed the African country into a financial crisis in 2016. More in detail, between 2012 and 2016 the Swiss bank authorized $1.3bn worth of loans to the Republic of Mozambique, to be used to finance government-sponsored investment schemes including maritime security projects and a state tuna fishery in the capital. However, a part of the funds was unaccounted for, and one of Mozambique’s contractors was later found to have arranged $50m worth of kickbacks for bankers at Credit Suisse in order to secure more favorable deals on the loans. After this incident, the International Monetary Fund stopped its financial aid to Mozambique, action that led the country to enter a recession in the subsequent years. Global regulators fined the Swiss bank more than $400m in 2021.

In the same year, Credit Suisse recorded a $5.5bn loss due to risky exposure it had to the US hedge fund Archegos Capital, which collapsed in March. The bank had indeed more than $20bn of exposure to investments related to the fund, equivalent to half of the bank’s equity cushion against potential losses. Even though Credit Suisse sued Archegos for potential deceit, a lack of proper risk management culture seems unambiguous.

Another collapse that negatively affected the bank’s performance due its poor risk management is the one of Greensill Capital, supply-chain lender whose loans were packaged and sold to Credit Suisse clients. The bank didn’t run a proper clients’ screening on the beneficiary of these loans, many of which ended up being very risky and defaulted in March 2021 after a scandal that involved the former UK Prime Minister David Cameron.

One of Credit Suisse’s first public scandals took place in 1986, when Ferdinand and Imelda Marcos were found to be clients of the bank. The Philippine dictator and his wife, indeed, had bank accounts under fake names where they stored part of the $5bn-$10bn they stole from the country during Ferdinand Marcos’ three terms of office. In 1995 a court ordered banks, including Credit Suisse, to return $500m of stolen funds to the Philippines, but the Swiss institution didn’t learn from its mistakes. As a matter of fact, during the 1990s, the bank accepted $214m worth of funds linked to corruption by Sani Abacha, Nigerian military dictator who stole millions of dollars from his own country and people. When charged by the Swiss Federal Bank, Credit Suisse stated that the political exposure of the client wasn’t known to the bankers who dealt with the operations. However, since the beginning of the 21st century, the promised improvement in the institution’s monitoring procedures hasn’t happened, with the Swiss bank being linked to the Japanese Yakuza and a Bulgarian drug ring that led it to face a criminal trial, the first one in history against a Swiss bank.

In addition to weak monitoring practices, the bank has been involved in many illegal financial conducts, among which we find tax evasions in numerous countries (Credit Suisse has been found guilty of this in Germany, the United States and Italy) and the Mozambique tuna bonds case, a loan bribery scandal that subsequently pushed the African country into a financial crisis in 2016. More in detail, between 2012 and 2016 the Swiss bank authorized $1.3bn worth of loans to the Republic of Mozambique, to be used to finance government-sponsored investment schemes including maritime security projects and a state tuna fishery in the capital. However, a part of the funds was unaccounted for, and one of Mozambique’s contractors was later found to have arranged $50m worth of kickbacks for bankers at Credit Suisse in order to secure more favorable deals on the loans. After this incident, the International Monetary Fund stopped its financial aid to Mozambique, action that led the country to enter a recession in the subsequent years. Global regulators fined the Swiss bank more than $400m in 2021.

In the same year, Credit Suisse recorded a $5.5bn loss due to risky exposure it had to the US hedge fund Archegos Capital, which collapsed in March. The bank had indeed more than $20bn of exposure to investments related to the fund, equivalent to half of the bank’s equity cushion against potential losses. Even though Credit Suisse sued Archegos for potential deceit, a lack of proper risk management culture seems unambiguous.

Another collapse that negatively affected the bank’s performance due its poor risk management is the one of Greensill Capital, supply-chain lender whose loans were packaged and sold to Credit Suisse clients. The bank didn’t run a proper clients’ screening on the beneficiary of these loans, many of which ended up being very risky and defaulted in March 2021 after a scandal that involved the former UK Prime Minister David Cameron.

Financial performance and stock developments

Credit Suisse capped a tumultuous year of managerial upheaval, investor outflows and a series of profit warnings with a 7.9bn $ annual loss compared to a 1.9bn $ loss in the previous year. 1.5bn $ alone resulted from the last three months, which were impacted by customer withdrawals, that amounted to over 100bn $ or 8% of total assets. Overall assets dropped 30% to 571bn $, and deposits fell 40% to 251bn $. The bank reported a 33% fall in revenues, mainly attributable to a 74% decline in investment banking fees, but wealth management revenues were also 17% down, and asset management income dropped by 28%. The annual loss was furthermore impacted by a write-down of deferred tax assets of almost 4.0bn $ in the third quarter. The write-down resulted from bleak future profit forecasts since deferred tax assets are only valuable for companies which generate profits.

In the last weeks and months, there have been some significant fluctuations in the bank's stock price development. The most severe decrease of roughly 23%, representing the most extensive one-day loss in the history of the stock, happened after a public announcement of the biggest shareholder of the bank, Saudi National Bank (SNB), which owns 9.9%. Saudi National Bank publicly stated on Wednesday, March 15th, that they would not provide additional capital to Credit Suisse if there were a call for additional equity. The chair of the SNB, Ammar Alkhudairy, justified the statement with the unwanted regulatory requirements in the case of owning more than 10% of Credit Suisse. The news amplified investors' concerns about the bank's ability to generate cash flows. There was a fear that shareholders needed to step in again for funding. Credit Default Swaps surged after the public statement and followed stock price decreases since many investors wanted to protect themselves against a possible default of the bank. The cost of insuring against a five-year senior debt of Credit Suisse in the amount of 10,000$ using a credit default swap costs around 1,000$ at the moment compared to 400$ at the beginning of 2023. Furthermore, prices of bonds from Credit Suisse fell to distressed levels and put-options on the stock outnumbered call-options.

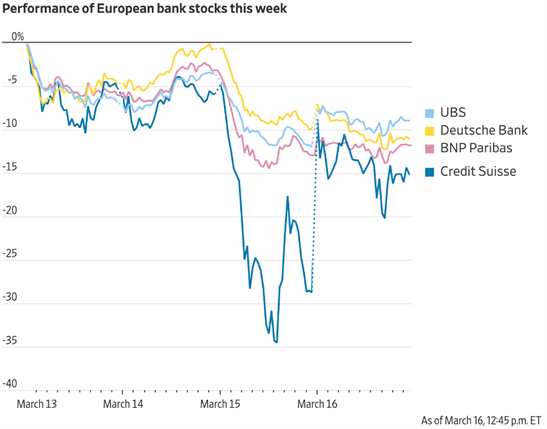

One day later, on Thursday, March 16th, the Swiss National Bank announced they would lend Credit Suisse more than 50bn $, which resulted in an increase in stock prices. According to Credit Suisse, the liquidity injection is aimed at sending positive feedback to clients and will be used to improve the liquidity coverage ratio of the bank to build up a cash buffer in case of future liquidity needs. Over a ten-year time horizon, the shares of Credit Suisse lost over 90% of their value and 26% in the week from March 13th to 17th. The slide of Credit Suisse shares reignited a broader sell-off in bank stocks in Europe and the US, which were reeling from the failure of Silicon Valley Bank. BNP Paribas, Deutsche Bank and UBS lost between 9% and 14%. In the US, JPMorgan and Citigroup declined 4.7% and 5.4%, respectively.

Additionally, the confidence of the bank's customers decreased tragically over the last months. It started in October 2022 with social media rumors about the bank's financial health, which resulted in material asset outflows, as mentioned earlier. The withdrawals of clients slowed down but continued in the following months until Credit Suisse needed to reach out to over 10,000 clients to reassure them of the bank's financial health. Further confidence was lost on Tuesday, 14th of March, as the auditor of Credit Suisse, PriceWaterhouseCoopers, revealed that they had identified "material weaknesses" in the financial reporting controls of the bank, which resulted in the delay of the publication of the annual report.

Capital ratios represent one of the most looked-after statistics for banks, especially for loss-making banks like Credit Suisse. Essential for the confidence of equity and debt investors is the Core Equity Tier 1 (CET1) capital ratio. For a large global bank like Credit Suisse, receiving a debt rating from one of the credit agencies above junk status is crucial, which the bank managed to do by just one notch. At the end of the financial year 2022, the bank had a CET1 ratio of 14.1%, representing a slight decrease of 0.3% compared to 2021. Forecasted ratios for 2023, 2024 and 2025 were 12.6%, 13.1% and 13.6%, respectively. Furthermore, the liquidity coverage ratio was around 144% at the end of the financial year 2022.

Is this a new 2008?

When evaluating the situation as a whole, it is important to acknowledge several consequential factors. For instance, the mechanisms under which the takeover occurred are also highly controversial: the Swiss state essentially canceled shareholders’ rights on both sides of the transaction and informed the management of Credit Suisse that a merger with UBS would be the only option. The initial offer for the transaction was around $1bn, or SFr0.25 per share - about 7 times less than the market share price. This was ultimately increased to $3.25bn, which still only represents about 7% of Credit Suisse’s book value, as a result of extended negotiations, which also guaranteed UBS access to sustained Swiss National Bank support under a loss guarantee of SFr9bn, in addition to a SFr100bn liquidity line. All in all, the opacity of the deal continues to be a great source of discontent among domestic and international investors alike.

It can reasonably be argued that Credit Suisse AT1 bondholders are bearing the brunt of the loss. The Swiss finance ministry, in an effort to appease international equity investors, outraged after the suspension of their voting rights, moved to impose losses amounting to SFr16bn on AT1 capital bonds. There is some speculation among financial analysts that this could greatly damage the reputation bonds carry as a low-risk financial asset, and push investors away from bonds, especially AT1 bonds, in the future. There are also several legal challenges that are gaining popularity among AT1 bond holders and, potentially, UBS shareholders outraged at not having a say in such a consequential transaction. It is also anticipated that tens of thousands of job losses will soon follow and both Moody and S&P now predict a “negative” outlook for UBS. Up to a third of jobs could be cut as UBS and Credit Suisse work to integrate overlapping departments. Heightened risk aversion may also mean that UBS will lose customers and have its reputation “polluted” by its association with CS.

The terrain for Credit Suisse’s “downfall” was primed by the recent turbulence of financial markets following the collapse of the Silicon Valley Bank. Although there is a natural tendency to compare the two, their internal structures were markedly different. SVB failed because its main customers were start-ups and venture capitalists, with deposits by far above the threshold insured by the FDIC, and was highly exposed to interest rate risk, despite no appropriate measures to contain and reduce said risk were adopted. Indeed, as of the end of 2022, SVB had not placed any interest-rate hedges on its bond portfolio, despite the sustained rise in US interest rates.

In contrast, Credit Suisse has had a long tradition of catering to billionaire investors and sovereign wealth funds. In terms of assets held, it was the second-largest Swiss bank and was widely considered very important to the European (and global) banking system. SVB’s paper losses totalled around $15bn, while the figure for CS was just around $50mn, a “virtual invisibility”, states the Wall Street Journal. In further comparison to the 2008 financial crisis, the problem with CS was not the lack of value of its held assets, but rather the liquidity crisis created as a result of plunging customer confidence, which has actually been compounding over time as Credit Suisse has consistently been losing money. It has been especially prone to “accidents” and failed to implement administrative changes. This is why the cost of “bailing” SVB and, in general, US banks has been much greater than anything we can expect to see in the case of Credit Suisse.

While this could lead to a broader crisis of confidence in the European banking system, analysts at the Financial Times argue that there is “less fundamental reason to distrust the viability of European banks more broadly”. Credit Suisse has long been problematic. This crisis rather highlights the resilience of other major European banks, with low credit losses, strong capital levels, and longevity in the face of stress tests. However, in the case (with slim chances) of another full financial meltdown, what is concerning is the fact that states no longer have the same resources as they did 15 years ago. High levels of inflation are keeping interest rates up and balance sheets are significantly more stretched after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Regulations: what lies ahead?

While the shotgun merger of UBS and Credit Suisse may have prevented the risk of contagion and a more regional systemic crisis, it has once again (GFC 2008) highlighted the question of moral hazard. When institutions become too large to fail, and recognize they have a tacit government back-stop, this can lead to excessive risk taking. The net result of the Credit Suisse failure in Europe is a further concentration of assets and risk in a few very large institutions. This may also over time further limit competition as the largest banks will have the advantage of scale that they can use to blunt their competitors actions. Ultimately time will tell whether this banking crisis has been averted or whether the pressures that have mounted in the system from rising interest rates will lead to a domino effect.

On Monday, March 20th, following the emergency rescue merger of UBS and Credit Suisse attention focused on AT1 Bonds, also known as CoCo Bonds or contingent convertibles, which traded down, some as much as 10bps, early in the European session. Investors were very surprised and worried that the Swiss decision to liquidate those holders might be mirrored in other markets. However, the European Banking Authority and ECB came out on Monday and clarified that shareholders should be the first to absorb losses with AT1 bonds required to be written off after all common equity Tier 1 (CET 1) capital has been exhausted. Importantly, stock markets later responded positively to the news of the UBS acquisition and the Stoxx Europe 600 Banks index closed 0.9% up for the day. In the US, the S&P 500 index closed the day with a 34 point gain as investors globally breathed a sigh of relief and as they evaluated the efforts to contain additional contagion and turmoil in the banking sector.

Conclusion

The solidity of the banking system is always threatened in times of crises. Credit Suisse is the perfect example of a weakened institution that, yet fragile, is extremely exposed to market events and raised concerns. While a banking crisis seems not to be on the horizon, this story raises lots of questions, yet to be answered, about what address regulators will take in the next year, and how they will design responses to face an always more and more concentrated banking sector.

By Georgia Mirica, Sara D’Apice, Lukas Brendel, Alexander Lockhart

SOURCES:

- Wall Street Journal

- Financial Times

- The Guardian