Introduction

Companies are always exposed to risk due to volatility and other market moving events and they manage this risk through using various financial instruments, hedging and other methods. This can be related to increased competition and high reliance on capital markets for long term funding. To hedge this risk companies often use derivatives. Derivatives are one of the most fascinating and yet risky financial instruments in the market. This article will describe the role of derivatives in the financial markets throughout history and how regulatory institutions in the US and EU are preventing the possible systemic impact of these financial instruments. Furthermore, we will analyse the current use of derivatives and the function of the VIX index to measure the strength of short term price change of SPX.

Derivatives: (potentially) bizarre financial instruments

Derivatives have become increasingly important in finance: futures and options are actively traded on many exchanges throughout the world, and many different types of forward contracts, swaps, options have been introduced in the OTC (Over-the-Counter) market by financial institutions. There are many types of derivatives available on every asset class, and the 2020 global gross market value of OTC derivatives market is estimated at over $15.5 trillion (Bank for International Settlement, 2020).

In order to understand the main functions of the derivative market, it is crucial to define this financial instrument. A derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the performance of the underlying entity, the most common are stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates and market indexes. However, the peculiarity (and riskiness) of these instruments is that they can be designed in complex ways to contemplate the possibility for the parties engaged in the agreement to “take a position” on different types of possible underlying assets. A quick examination of the principal types of derivative instruments may be useful to frame the issue.

Two relevant classes of derivative instruments are future and forward contracts: they are an agreement between two parties for the purchase and delivery of an asset at a given date and at an established price. While the former is a highly standardized contract trading on a regulated Exchange, the latter is an OTC product allowing buyers and sellers to agree on customized terms and therefore bearing a high degree of counterparty risk for both.

In order to understand the main functions of the derivative market, it is crucial to define this financial instrument. A derivative is a financial instrument whose value is derived from the performance of the underlying entity, the most common are stocks, bonds, commodities, currencies, interest rates and market indexes. However, the peculiarity (and riskiness) of these instruments is that they can be designed in complex ways to contemplate the possibility for the parties engaged in the agreement to “take a position” on different types of possible underlying assets. A quick examination of the principal types of derivative instruments may be useful to frame the issue.

Two relevant classes of derivative instruments are future and forward contracts: they are an agreement between two parties for the purchase and delivery of an asset at a given date and at an established price. While the former is a highly standardized contract trading on a regulated Exchange, the latter is an OTC product allowing buyers and sellers to agree on customized terms and therefore bearing a high degree of counterparty risk for both.

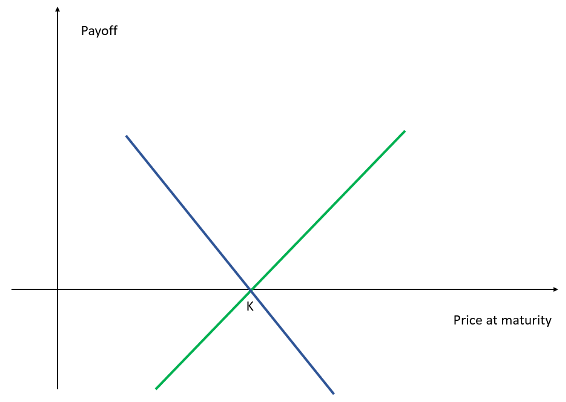

Payoff of Long Forward (positive slope) and Short Forward (negative slope)

According to the Bank for International Settlement, as of June 2019 60% of the global OTC derivatives market in terms of notional value was represented by Interest Rate Swaps, peculiar types of Swap contracts. The latter is an agreement between two counterparties (the so-called long leg and short leg) to exchange cash flows in the future (in the specific case of the IRS, these CFs are a function of two different interest rates).

An important part of the global derivatives market is made of Option contracts. An option is an agreement by two parties establishing the right – not the obligation – for the buyer to buy or sell the underlying asset at a predefined price (Strike price) at a pre-established expiration date. Option contracts may have different characteristics based on the underlying asset and in terms of settlement date. What makes them so fascinating is that their value depends on many risk factors (the price and volatility of the underlying asset, the time to maturity and eventually the interest rate) which influence options’ prices dynamically. When referring to option contracts, the most important distinction is the so-called “plain vanilla options” (European and American options) and “Exotic options”, where the construction of the derivative is complex and the payoff is often defined in creative ways.

An important part of the global derivatives market is made of Option contracts. An option is an agreement by two parties establishing the right – not the obligation – for the buyer to buy or sell the underlying asset at a predefined price (Strike price) at a pre-established expiration date. Option contracts may have different characteristics based on the underlying asset and in terms of settlement date. What makes them so fascinating is that their value depends on many risk factors (the price and volatility of the underlying asset, the time to maturity and eventually the interest rate) which influence options’ prices dynamically. When referring to option contracts, the most important distinction is the so-called “plain vanilla options” (European and American options) and “Exotic options”, where the construction of the derivative is complex and the payoff is often defined in creative ways.

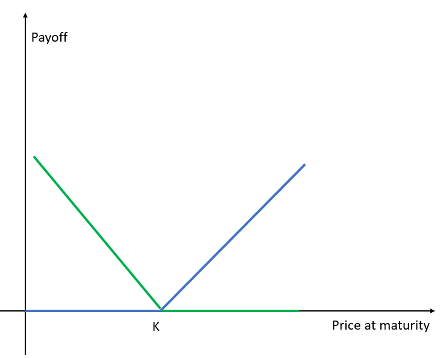

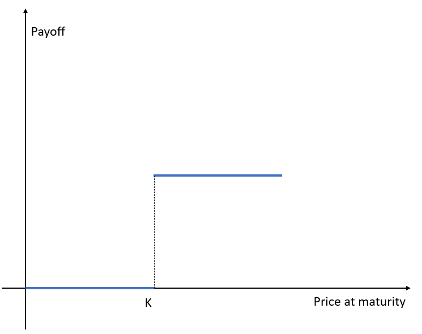

Payoff of a long put option and a long call option (“plain vanilla options”) as opposed to the P&L at maturity of one of the simples exotic options: the digital call

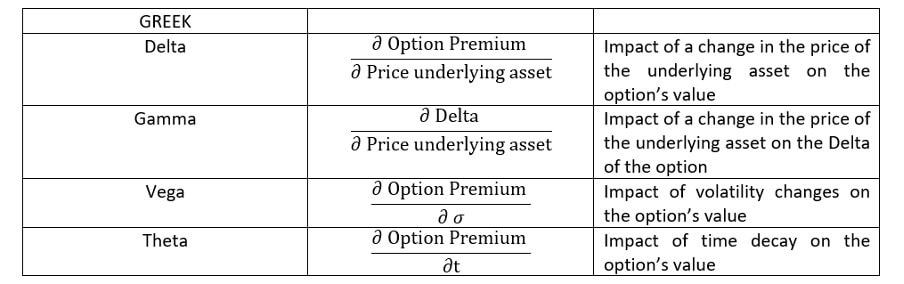

While plain vanilla and exotic options differ a lot in terms of options’ sensitivity to each of the risk factors mentioned above, this element is carefully monitored by traders and market makers to evaluate their positions. Options’ sensitivity to each risk factor can be measured through the so called Greeks, which are nothing else than partial derivatives of the option’s value respective to each risk factor: while Delta and Gamma measure the sensitivity of the option’s price to changes in the value of the underlying asset, Vega accounts for the effect of underlying asset’s volatility changes on the price of the option and Theta represents the effect of the reduction of the option’s value as time passes.

Greeks table (name, formula and definition)

The evolution of derivatives throughout history

Throughout human history we have seen the evolution of the derivatives market ranging from Thales of Miletus becoming the world’s first oil derivatives trader in ~600BC, to the current global derivatives market estimated to be valued at roughly $1 Quadrillion as of 2020. While these financial instruments allow investors to hedge and mitigate risk in certain market environments, they can also be misused and have tremendous economic consequences. Some of these derivatives such as credit default swaps, or total return swaps have caused unthinkable economic damage. Over the past few decades, there have been several monumental events that involved derivatives and shook the world. Ranging from the 1998 Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) collapse, the GFC in 2008, to Archegos in 2021, derivatives were a key reason for the occurrence of all these historical market events.

The collapse of LTCM in 1998 rippled through global markets and the stability of the financial system itself fell into question. Founded in 1994, LTCM was a hedge fund based in Greenwich Connecticut that employed absolute-return trading strategies combined with high financial leverage in derivative instruments. In the first three years, the firm saw huge success with over 40% annualized returns in both the second and third year. LTCM focused on convergence trades, which involved taking advantage of arbitrage opportunities between mispriced bond securities. They also dealt with interest rate swaps, involving the exchange of one series of future interest payments for another, based on a specified principal payment between two counterparties. Due to the small spreads on arbitrage opportunities, LTCM needed to use a significant amount of leverage and by 1998 the firm had amassed $5 billion in assets and controlled over $100 billion, and had positions whose total worth was over $1 trillion. However, the success of the firm had come to an end in 1998 when it lost $4.6 billion in just four months due to the leverage it was taking on its derivative positions. The combination of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the Russian financial crisis in 1998 were the root cause.

In the 1990s, credit default swaps (CDS) were first used by banks as private transactions between banks to hedge risk by transferring the credit risk of a borrower and to free up regulatory capital. As time moved on, hedge funds, asset managers and other institutional investors recognized the potential of this financial instrument and quickly began trading them as well. The key reason for this was CDS transformed bond trading into a highly leveraged and high-velocity business that appeared to be low risk with the potential for consistent premiums. As a result, the CDS market exploded over the course of the decade, and by the end of 2007 the market value was close to $62 Trillion. The reason this quickly came to an end was because many of the CDS were sold to investors as insurance against collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), financial instruments that pay investors from a pool of revenue-generating sources, typically mortgages. The combination of little regulatory oversight of banks, the fact that the products they were selling were backed by credit rating agencies and a lack of effective oversight by government agencies responsible for protecting consumers. As a result, the housing market started to collapse, the value of the CDOs and mortgages became worthless and almost all the banks and hedge funds had to start paying out big money.

The 2008 financial crisis that devastated the world economy could have been anticipated if not prevented. The government's failure to properly regulate its own agencies and the private sector, combined with private sector’s greed for profit, set the stage for this catastrophic meltdown in the mortgage market. Governments need to wield their powers with a focus on promoting the best outcomes for their people and the stability of markets. When they fail to uphold these goals, the consequences can be calamitous.

More recently, Archegos Capital, a family investment vehicle owned by Bill Hwang, a former employee of Julian Robertson, triggered a process that ultimately cost several Investment Banks billions in losses during March. This forced liquidation caused a rapid unwinding of positions that were built through derivative exposure. Archegos is estimated to have been managing roughly $10 billion but he gained an additional exposure estimated to be $30 billion. Archegos took very large positions in companies and held some of these positions through total-return swaps, which are brokered by banks and allow the user to take on profits or losses of a company in exchange for a fee. The context for the collapse came from the combination of Chinese tech company share prices declining as well as ViacomCBS issuing more common stock. Archegos found itself at a large loss and began selling shares through block trades. Credit Suisse, Nomura, Morgan Stanley, and other investment banks took meaningful losses as a result of providing prime brokerage services to Archegos. In summary, a lack of transparency, poor risk management by banks, the use of very significant amounts of derivatives to gain exposure came together to forced selling and price declines that resulted in substantial losses that have yet to be fully understood by investment banks.

The collapse of LTCM in 1998 rippled through global markets and the stability of the financial system itself fell into question. Founded in 1994, LTCM was a hedge fund based in Greenwich Connecticut that employed absolute-return trading strategies combined with high financial leverage in derivative instruments. In the first three years, the firm saw huge success with over 40% annualized returns in both the second and third year. LTCM focused on convergence trades, which involved taking advantage of arbitrage opportunities between mispriced bond securities. They also dealt with interest rate swaps, involving the exchange of one series of future interest payments for another, based on a specified principal payment between two counterparties. Due to the small spreads on arbitrage opportunities, LTCM needed to use a significant amount of leverage and by 1998 the firm had amassed $5 billion in assets and controlled over $100 billion, and had positions whose total worth was over $1 trillion. However, the success of the firm had come to an end in 1998 when it lost $4.6 billion in just four months due to the leverage it was taking on its derivative positions. The combination of the Asian financial crisis in 1997 and the Russian financial crisis in 1998 were the root cause.

In the 1990s, credit default swaps (CDS) were first used by banks as private transactions between banks to hedge risk by transferring the credit risk of a borrower and to free up regulatory capital. As time moved on, hedge funds, asset managers and other institutional investors recognized the potential of this financial instrument and quickly began trading them as well. The key reason for this was CDS transformed bond trading into a highly leveraged and high-velocity business that appeared to be low risk with the potential for consistent premiums. As a result, the CDS market exploded over the course of the decade, and by the end of 2007 the market value was close to $62 Trillion. The reason this quickly came to an end was because many of the CDS were sold to investors as insurance against collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), financial instruments that pay investors from a pool of revenue-generating sources, typically mortgages. The combination of little regulatory oversight of banks, the fact that the products they were selling were backed by credit rating agencies and a lack of effective oversight by government agencies responsible for protecting consumers. As a result, the housing market started to collapse, the value of the CDOs and mortgages became worthless and almost all the banks and hedge funds had to start paying out big money.

The 2008 financial crisis that devastated the world economy could have been anticipated if not prevented. The government's failure to properly regulate its own agencies and the private sector, combined with private sector’s greed for profit, set the stage for this catastrophic meltdown in the mortgage market. Governments need to wield their powers with a focus on promoting the best outcomes for their people and the stability of markets. When they fail to uphold these goals, the consequences can be calamitous.

More recently, Archegos Capital, a family investment vehicle owned by Bill Hwang, a former employee of Julian Robertson, triggered a process that ultimately cost several Investment Banks billions in losses during March. This forced liquidation caused a rapid unwinding of positions that were built through derivative exposure. Archegos is estimated to have been managing roughly $10 billion but he gained an additional exposure estimated to be $30 billion. Archegos took very large positions in companies and held some of these positions through total-return swaps, which are brokered by banks and allow the user to take on profits or losses of a company in exchange for a fee. The context for the collapse came from the combination of Chinese tech company share prices declining as well as ViacomCBS issuing more common stock. Archegos found itself at a large loss and began selling shares through block trades. Credit Suisse, Nomura, Morgan Stanley, and other investment banks took meaningful losses as a result of providing prime brokerage services to Archegos. In summary, a lack of transparency, poor risk management by banks, the use of very significant amounts of derivatives to gain exposure came together to forced selling and price declines that resulted in substantial losses that have yet to be fully understood by investment banks.

Regulation on derivatives

In the EU, Central Clearing Counterparties (CCP) are the intermediary between counterparties of a derivative contract. By doing so, CCPs represent the core pillar of derivative transactions to incentivise market transparency and reduce the default risk implicit in derivatives markets.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, derivatives traded outside regulated markets were usually not analysed through CCPs. But after an increasing necessity to provide more transparency to the investors, nowadays CCPs analyse thousands of financial transactions in a range of financial instruments. The central data centre which collects the records of derivative transactions is called Trade repositories and plays a crucial role in enhancing the clarity of derivative markets and reducing risks. The acknowledgment of the risks associated with derivatives was first highlighted during the 2008 financial crisis, when significant weaknesses in the OTC markets became very evident. Therefore EU countries funded a regulatory institution in 2012 called European market infrastructure regulation (EMIR).

The roles of EMIR are:

Enhancing transparency

Mitigating credit risk

Reducing operational risk

On the other hand, US regulation is structured through a different model: option contracts traded over stock are controlled by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) while options contracts over forex and futures are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). In 2000, the SEC was unable to force companies to abide by reporting or disclosure requirements in order to prevent fraud. As a result, the SEC's ability to deter fraud in the swaps markets was limited. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act covered this gap in the american financial regulation of OTC swaps by providing a comprehensive framework for the regulation of the OTC swaps markets. The Dodd-Frank Act separate regulatory power over swap contracts agreements between the CFTC and SEC. The SEC has control over “security-based swaps”, defined as single security swaps or a narrow-based group or index of securities. Security-based swaps are within the definition of “security” written in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The CFTC has primary regulatory authority over all other swaps, such as energy and agricultural swaps whereas the control over the so called “mixed swaps” ,which are security-based swaps that also have a commodity component, is shared between the two authorities.

Since the 2008 financial crisis, derivatives traded outside regulated markets were usually not analysed through CCPs. But after an increasing necessity to provide more transparency to the investors, nowadays CCPs analyse thousands of financial transactions in a range of financial instruments. The central data centre which collects the records of derivative transactions is called Trade repositories and plays a crucial role in enhancing the clarity of derivative markets and reducing risks. The acknowledgment of the risks associated with derivatives was first highlighted during the 2008 financial crisis, when significant weaknesses in the OTC markets became very evident. Therefore EU countries funded a regulatory institution in 2012 called European market infrastructure regulation (EMIR).

The roles of EMIR are:

Enhancing transparency

- Accurate information on derivative contracts has to be registered in trade repositories data and be visible to supervisory authorities.

- Trade repositories have to disclose aggregate positions in terms of derivative classes both for OTC and listed derivatives.

Mitigating credit risk

- Every OTC derivatives contract have to be analysed through CCPs.

- CCPs must adhere with strict conduct requirements of business.

Reducing operational risk

- Market participants have to monitor and mitigate the operational risks such as fraud and human error.

On the other hand, US regulation is structured through a different model: option contracts traded over stock are controlled by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) while options contracts over forex and futures are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). In 2000, the SEC was unable to force companies to abide by reporting or disclosure requirements in order to prevent fraud. As a result, the SEC's ability to deter fraud in the swaps markets was limited. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act covered this gap in the american financial regulation of OTC swaps by providing a comprehensive framework for the regulation of the OTC swaps markets. The Dodd-Frank Act separate regulatory power over swap contracts agreements between the CFTC and SEC. The SEC has control over “security-based swaps”, defined as single security swaps or a narrow-based group or index of securities. Security-based swaps are within the definition of “security” written in the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The CFTC has primary regulatory authority over all other swaps, such as energy and agricultural swaps whereas the control over the so called “mixed swaps” ,which are security-based swaps that also have a commodity component, is shared between the two authorities.

Current market conditions

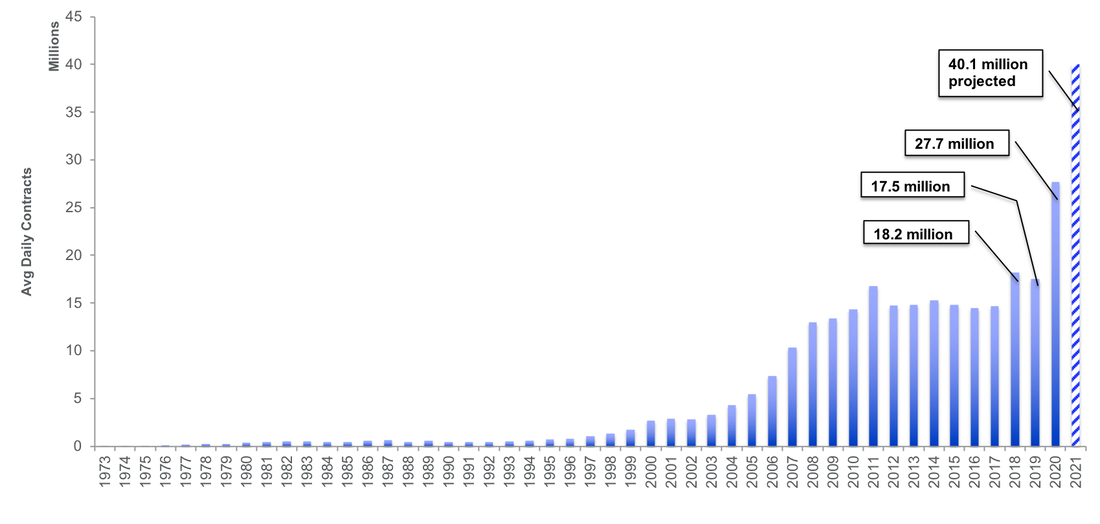

Over the past several months markets have been very volatile and there appears to be many reasons as to why there continues to be such market froth. One of these factors that explain that recent turbulence, is the continued increase in equity option trading volumes. The average daily volume (ADV) of trading in option contracts has dramatically increased in recent years, and is projected to reach an 40 million in 2021, which is more than double the contracts traded in 2019.

The VIX, otherwise known as the “fear gauge” measures the implied volatility in S&P 500 options, and is used as price protection against sharp market declines. Following the pandemic market crash in 2020, the VIX remained at historically elevated levels for almost one year and only recently returned to closing under the psychological 20 level. Over the past six to eight weeks, the markets have calmed due to positive vaccination results, strong recovery in employment and earnings driven by fiscal and monetary support. While the results are promising, it is likely the VIX returns to more elevated levels as investors realise the true long term consequences of the pandemic.

The VIX, otherwise known as the “fear gauge” measures the implied volatility in S&P 500 options, and is used as price protection against sharp market declines. Following the pandemic market crash in 2020, the VIX remained at historically elevated levels for almost one year and only recently returned to closing under the psychological 20 level. Over the past six to eight weeks, the markets have calmed due to positive vaccination results, strong recovery in employment and earnings driven by fiscal and monetary support. While the results are promising, it is likely the VIX returns to more elevated levels as investors realise the true long term consequences of the pandemic.

Equity and ETF Options Average Daily Volume. Source: Traders Magazine

Conclusions

Derivatives can be effective financial instruments when used for hedging, improving the efficiency of financial markets and helping access to unavailable markets or assets. Nevertheless, if they are misused or overused, the resulting consequences can be calamitous. If history reveals anything, it is that the derivatives market should receive more regulatory oversight in order to avoid the potential catastrophic impact on financial markets and to preserve the soundness of the financial realm as a whole but of course should still be allowed some freedom to provide investors with alternative investment strategies.

Chiara Pampillonia

Guglielmo Palmieri

Nicolas Lockhart

Guglielmo Palmieri

Nicolas Lockhart

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.