Before the pandemic: Decreasing returns in an ever more competitive industry

Even before the pandemic, throughout 2019 and in the first quarter of 2020, economies around the globe were slowing down.

A growing expectation of a global recession among private equity fund general partners (GPs) lead them to alter their investment strategies by accelerating exits and assessing recession-related risks with caution. Furthermore, overheated asset valuations (GPs No. 1 source of anxiety according to Preqin investor interviews) pushed by aggressive corporate buyers and a crowded marketplace cut investment opportunities.

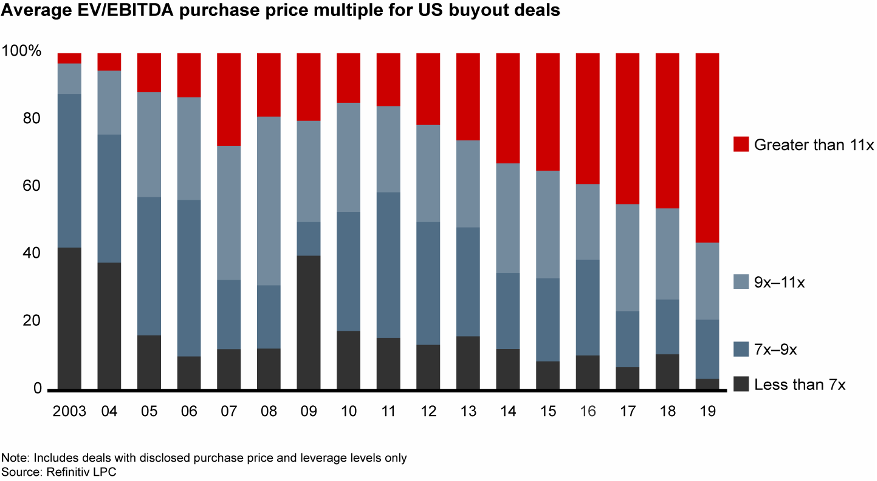

This can be seen in the average multiple of enterprise value (EV) to EBITDA for a leveraged buyout (LBO), which reached a record 11.5x in the US. Figure1 eloquently illustrates the inflation in valuations as a result of the increasing competitiveness in the market.

Even before the pandemic, throughout 2019 and in the first quarter of 2020, economies around the globe were slowing down.

A growing expectation of a global recession among private equity fund general partners (GPs) lead them to alter their investment strategies by accelerating exits and assessing recession-related risks with caution. Furthermore, overheated asset valuations (GPs No. 1 source of anxiety according to Preqin investor interviews) pushed by aggressive corporate buyers and a crowded marketplace cut investment opportunities.

This can be seen in the average multiple of enterprise value (EV) to EBITDA for a leveraged buyout (LBO), which reached a record 11.5x in the US. Figure1 eloquently illustrates the inflation in valuations as a result of the increasing competitiveness in the market.

Nonetheless, global PE activity did not slow much in 2019. Public-to-private (P2P) transactions boosted deal-making (eight of the year’s top ten buyouts involved public companies taken private) and the growing stake of deals co-sponsored by Limited Partners (LPs) allowed for a number of record mega-deals. This demonstrates how funds were (and still are) broadening their scope of investment in their almost desperate struggle to propel returns, which were, for the first time in decades, converging with those of public equity. In fact, buyout funds had a 10-year IRR of 15.3% against a return of 15.5% for the U.S. stock market.

Taking the hit: revised strategies during Covid-19

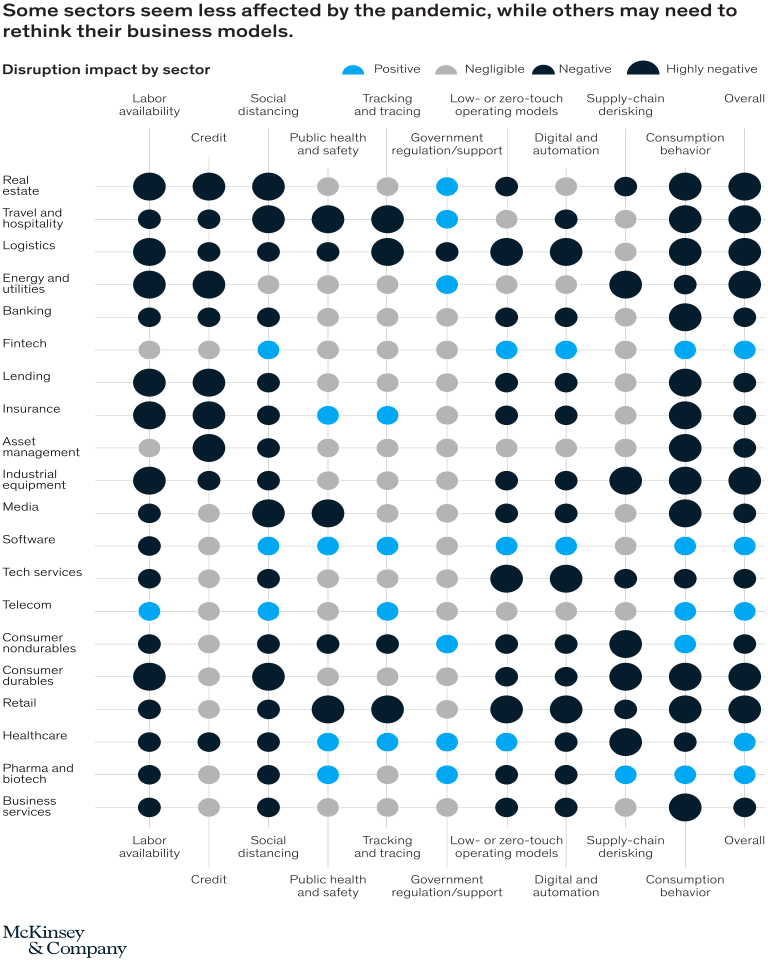

The slowdown caused by the adverse effect of the pandemic on PE activity became evident in the second quarter of 2020, with buyouts and fundraising in significant decline. Both the value and number of buyout-backed deals were nearly half of those seen in Q2 2019. However, the disruption has substantial cross-sector differences as is exhibited in Figure 2, which shows the sign and size of the impact caused by various disruption factors in 20 sectors.

Taking the hit: revised strategies during Covid-19

The slowdown caused by the adverse effect of the pandemic on PE activity became evident in the second quarter of 2020, with buyouts and fundraising in significant decline. Both the value and number of buyout-backed deals were nearly half of those seen in Q2 2019. However, the disruption has substantial cross-sector differences as is exhibited in Figure 2, which shows the sign and size of the impact caused by various disruption factors in 20 sectors.

Furthermore, investors' appetite has decreased: the proportion of investors looking to commit more than $300mln in the next 12 months has gone from 22% in Q2 2019 to 11% in Q2 2020. Nevertheless, the proportion of those looking to commit less than $50mln has remained stable, suggesting compression at the top end rather than a general fall in investor enthusiasm.

On a more sanguine note, an S&P survey suggests that partners across the globe (80%) are confident that they have enough liquidity to support their portfolio companies in the coming months. However, to achieve sustainability in such an uncertain transition phase, firms have already started adapting to the new reality and pivoting their strategies toward both portfolio stabilization and to exploit potentially successful post-pandemic opportunities.

As central banks worldwide have taken drastic measures and injected as much as $9 trillion into financial assets, as opposed to the $2 trillion used during the global financial crisis of 2008–09, markets have recovered and now fall slightly short of their Q1 levels. Unfortunately, the additional liquidity hides the true value of underlying assets. Thus, the most pressing challenge for managers in Private Equity funds is to discern companies with a healthy balance sheet and medium-to-long-term prospects of growth from the growing pile of zombie companies living off record cash-injections.

What’s next? The role of PE’s excess cash and long-term investment strategy in the recovery

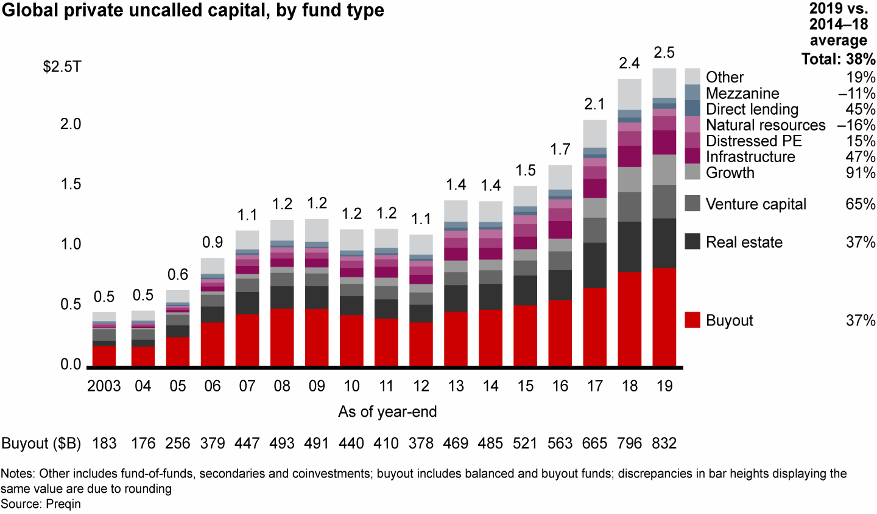

PE dry powder, or uncalled capital, has been rising since 2012, notwithstanding the industry’s steady pace of investments, hitting a record high of $2.5 trillion in December 2019 (Figure3). More than half of it sits in the United States. However, PE firms are accumulating mostly “young” capital, raised by funds with recent vintages: only 20% of all dry powder is pre-2015. This figure is crucial to understand the unique opportunity that the industry might enjoy during this global health crisis: the recent deal cycle is clearing out the older capital and replacing it with new, making the mountains of excess cash available for investment even years from today.

On a more sanguine note, an S&P survey suggests that partners across the globe (80%) are confident that they have enough liquidity to support their portfolio companies in the coming months. However, to achieve sustainability in such an uncertain transition phase, firms have already started adapting to the new reality and pivoting their strategies toward both portfolio stabilization and to exploit potentially successful post-pandemic opportunities.

As central banks worldwide have taken drastic measures and injected as much as $9 trillion into financial assets, as opposed to the $2 trillion used during the global financial crisis of 2008–09, markets have recovered and now fall slightly short of their Q1 levels. Unfortunately, the additional liquidity hides the true value of underlying assets. Thus, the most pressing challenge for managers in Private Equity funds is to discern companies with a healthy balance sheet and medium-to-long-term prospects of growth from the growing pile of zombie companies living off record cash-injections.

What’s next? The role of PE’s excess cash and long-term investment strategy in the recovery

PE dry powder, or uncalled capital, has been rising since 2012, notwithstanding the industry’s steady pace of investments, hitting a record high of $2.5 trillion in December 2019 (Figure3). More than half of it sits in the United States. However, PE firms are accumulating mostly “young” capital, raised by funds with recent vintages: only 20% of all dry powder is pre-2015. This figure is crucial to understand the unique opportunity that the industry might enjoy during this global health crisis: the recent deal cycle is clearing out the older capital and replacing it with new, making the mountains of excess cash available for investment even years from today.

Thus, private equity capital may have the dual advantage of helping businesses weather the storm while, in turn, providing funds with good deals at favorable valuations to put their vast stores of uncalled capital to work.

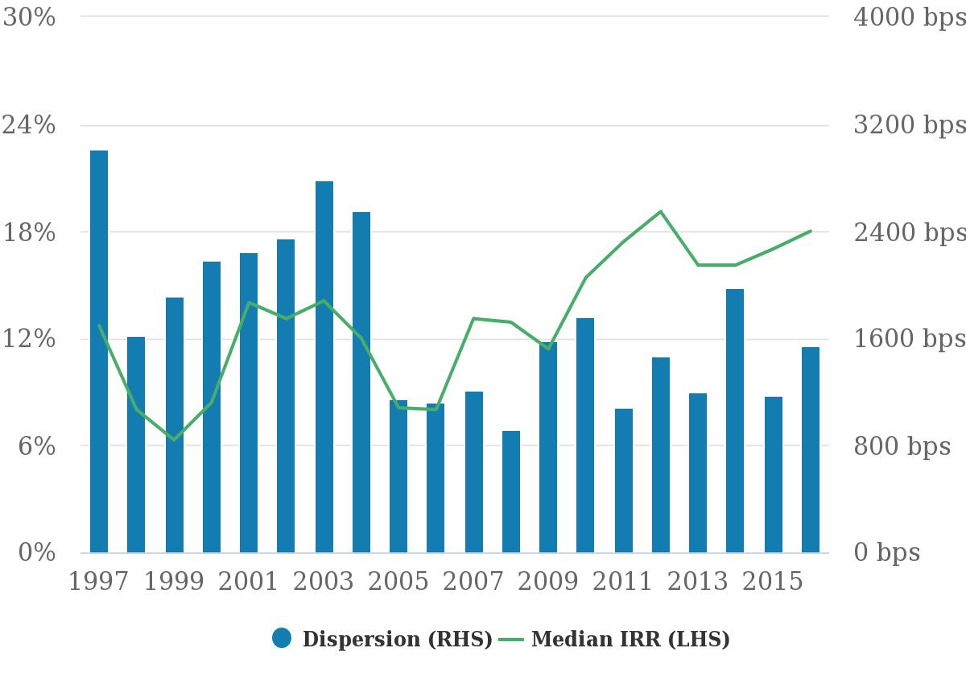

Furthermore, data referring to prior cycles show returns for private equity positions made following recessions outperforming those of other periods. In Figure 4, the aforementioned returns are measured based on the vintage year, which is the year a fund begins investing in companies to build its portfolio.

In the past two decades, funds that started deploying cash following a crisis (such as 2001 to 2004, after the dot-com bubble burst, or 2009 to 2012, after the global financial crisis) performed 68% higher than funds whose vintage years fell during late-cycle peak economic growth (such as 1998 to 2000 or 2005 to 2007).

Is this a good moment to invest in PE funds? Will funds be able to grasp these opportunities while avoiding losing too much on their current businesses?

Private Equity Returns by Vintage Years

Furthermore, data referring to prior cycles show returns for private equity positions made following recessions outperforming those of other periods. In Figure 4, the aforementioned returns are measured based on the vintage year, which is the year a fund begins investing in companies to build its portfolio.

In the past two decades, funds that started deploying cash following a crisis (such as 2001 to 2004, after the dot-com bubble burst, or 2009 to 2012, after the global financial crisis) performed 68% higher than funds whose vintage years fell during late-cycle peak economic growth (such as 1998 to 2000 or 2005 to 2007).

Is this a good moment to invest in PE funds? Will funds be able to grasp these opportunities while avoiding losing too much on their current businesses?

Private Equity Returns by Vintage Years

Preqin data as of May 2020 for December 31, 2019 values.

Article by Tommaso Scarlatti

Article by Tommaso Scarlatti