Public Equity Markets Overview

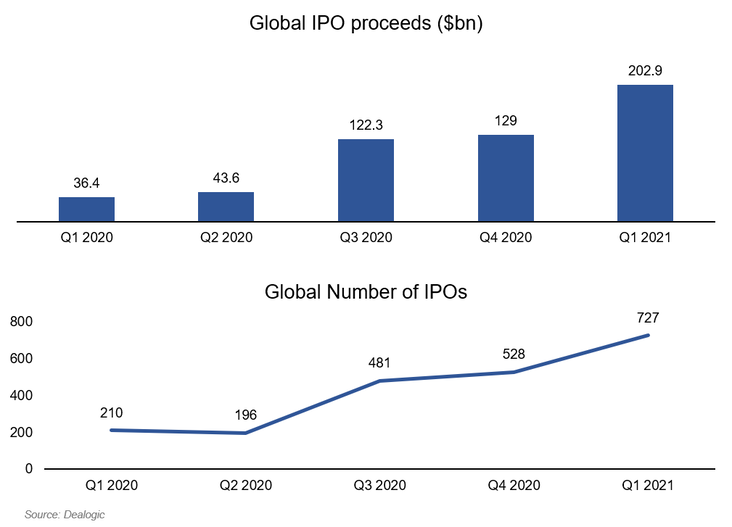

2021 is highlighted by the revival and boom of both IPO and SPAC IPOs, while volume in Direct Listing transactions is relatively low but also features some interesting transactions. In 2021 the market of IPOs is recovering after a year of difficulties. In particular, proceeds in the first quarter of 2021 are already more than 60% of the total proceeds of the whole 2020. The number of IPOs has also raised from 210 in 2020Q1 to 727 in 2021Q1. This appears in result of improvements in the economic cycle and vaccines diffusion. The United States account for 68% of the proceeds of 2021Q1, Mainland China 6% and Hong Kong 5%.

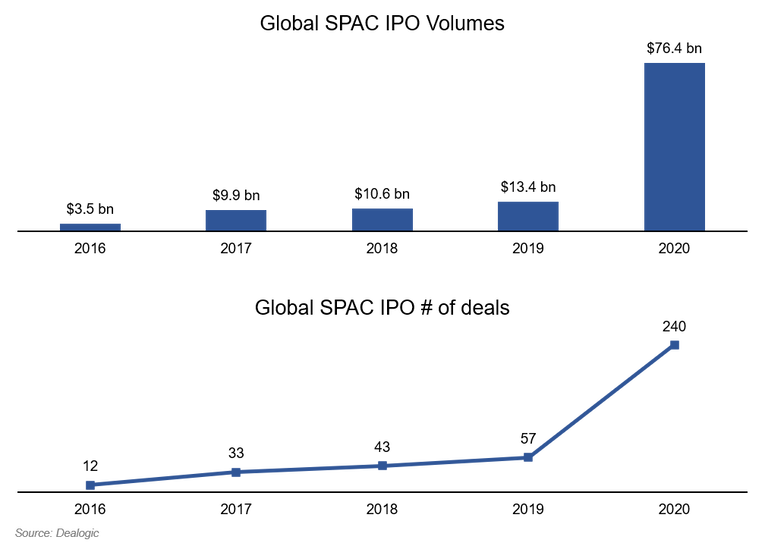

Concerning SPAC IPOs, volumes have been meaningfully increasing overtime going from $3.5bn in FY 2016 to $76.4bn in FY 2020 (as for the number of deals which went from 12 to 240). With regards to sector evolution, deals in 2016 were more general focused (50% of deals) while in 2020 they were more diversified among the different sectors (general, telecommunications, financial institutions, healthcare etc). From a size perspective, the average IPO size in 2016 was $291 million with 3 SPACS above $500m and the largest DeSPAC EV of $2.3bn. In 2020, the average IPO size was $318m with 28 SPACs above $500m and the largest DeSPAC EV of $16.1bn. We saw the emergence of repeat SPAC issuers and highly successful SPAC transactions.

2021 is highlighted by the revival and boom of both IPO and SPAC IPOs, while volume in Direct Listing transactions is relatively low but also features some interesting transactions. In 2021 the market of IPOs is recovering after a year of difficulties. In particular, proceeds in the first quarter of 2021 are already more than 60% of the total proceeds of the whole 2020. The number of IPOs has also raised from 210 in 2020Q1 to 727 in 2021Q1. This appears in result of improvements in the economic cycle and vaccines diffusion. The United States account for 68% of the proceeds of 2021Q1, Mainland China 6% and Hong Kong 5%.

Concerning SPAC IPOs, volumes have been meaningfully increasing overtime going from $3.5bn in FY 2016 to $76.4bn in FY 2020 (as for the number of deals which went from 12 to 240). With regards to sector evolution, deals in 2016 were more general focused (50% of deals) while in 2020 they were more diversified among the different sectors (general, telecommunications, financial institutions, healthcare etc). From a size perspective, the average IPO size in 2016 was $291 million with 3 SPACS above $500m and the largest DeSPAC EV of $2.3bn. In 2020, the average IPO size was $318m with 28 SPACs above $500m and the largest DeSPAC EV of $16.1bn. We saw the emergence of repeat SPAC issuers and highly successful SPAC transactions.

IPO

Overview

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is the oldest and most known process by which a private company sells its shares to the general public. Shares are usually sold to institutional investors, retail investors and hedge funds. IPOs are underwritten by investment banks, which are in charge of arranging the shares and the listing on stock exchanges. A firm may decide to go public to gain visibility in a foreign market, to raise capital for strategic growth or to provide an exit option to the existing shareholders.

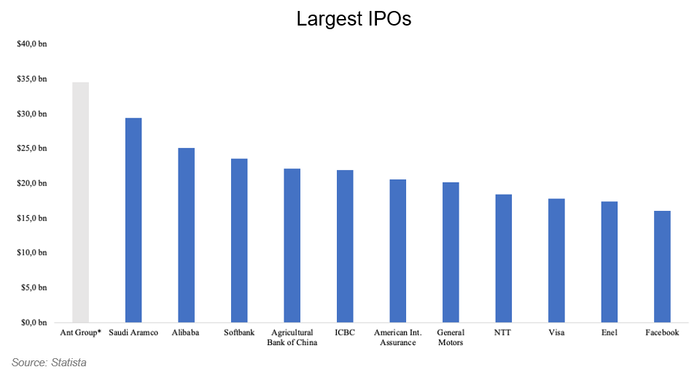

The first modern IPO was introduced in 1602 by the Dutch East India Company, that offered its shares to the public, becoming the first listed company on an official stock exchange. Since that time, IPOs have grown in value, reaching the record amount of $29.4bn in 2019 with the listing of Saudi Aramco. Ant Group in early 2021 would have become the first in the league, with expected $34.5bn raised, but the Chinese Government halted the process.

Overview

An Initial Public Offering (IPO) is the oldest and most known process by which a private company sells its shares to the general public. Shares are usually sold to institutional investors, retail investors and hedge funds. IPOs are underwritten by investment banks, which are in charge of arranging the shares and the listing on stock exchanges. A firm may decide to go public to gain visibility in a foreign market, to raise capital for strategic growth or to provide an exit option to the existing shareholders.

The first modern IPO was introduced in 1602 by the Dutch East India Company, that offered its shares to the public, becoming the first listed company on an official stock exchange. Since that time, IPOs have grown in value, reaching the record amount of $29.4bn in 2019 with the listing of Saudi Aramco. Ant Group in early 2021 would have become the first in the league, with expected $34.5bn raised, but the Chinese Government halted the process.

Process

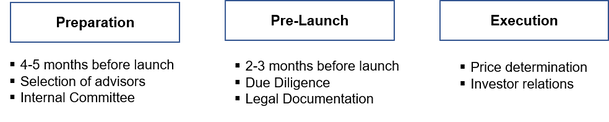

An IPO process may last several months, and it is led by the investment banks that are mandated as global coordinators. The preparation phase is usually started 4-5 months before the launch of the IPO: advisors are selected, an internal committee is created, and the strategic issues of the transaction are addressed. The due diligence is then performed in the pre-launch phase (3 months before the IPO), which starts with a kick-off meeting of all the parties involved. The legal documentation is hence prepared and a filing procedure with the appropriate regulator is started. The valuation of the company is an ongoing procedure that is constantly updated and revised taking into consideration the demand of investors. The third and last phase is the execution, in which the final price is determined through the book building process. The latter consists in capturing demand by collecting bids of investors. In an IPO process usually a mixture of both primary and secondary shares is offered. The former lead to an increase in the capital of the company while the second represent an exit option for current shareholders.

Stabilisation - Greenshoe Option

Underwriters have the right to sell more than the initially planned shares if the demand is higher than expected. Usually, 15% more shares are sold in the market, and within 30 days from the IPO, the underwriting bank may buyback those shares to stabilize the price and support demand. If instead the price of the stock increases, the greenshoe option is exercised and the shares are left in the market, providing extra profit.

Advantages

The first main advantage of an IPO is that it gives the company the possibility to reach a wide and diversified equity base: money is directly collected and can be used for growth or debt repayment. Early investors may also decide to monetize their exposure by selling their shares to the public, exercising an exit option. Shares can also be interpreted as a currency for future acquisitions, facilitating the process. Managers are usually paid with stock options, and this aligns their incentives to the shareholders’ objectives. The new public company gains prestige and exposure and achieves an objective valuation by investment banks. These act as underwriters in the process, bearing the risk that the shares may not be fully allocated. Underwriters may also stabilize the price through the greenshoe option. Usually, a syndicate of banks is created, in order to share the danger of an unsuccessful IPO. Moreover, the book building process is led by investment banks, which allocate together with the company the final shares. Time horizon and strategy of investors are considered, in order to guarantee a liquid secondary market and stability in the market. Indeed, a mixture of institutional investors, retail and hedge funds is involved.

Disadvantages

Primarily, running an IPO is expensive. Companies must bear significant legal, marketing and accounting costs. Investment banks usually receive fees in the range of 1.5% to 5%, depending on the size. In the US fees are higher than in Europe, and in Nordic regions they may even fall below 1%. In particular, Global Coordinators are in charge of overseeing the entire process, Bookrunners are responsible for the pricing, allocation and preparation of documents and Co-Lead Managers support coverage and marketing. Other advisors (legal, audit, specific experts) are required, raising the costs of the process. An IPO requires time and effort by the management of the company, and it may last more than a year from the first internal meetings to the final execution.

Case: Airbnb IPO

Airbnb is an online platform that connects property owners to travelers for lodging. It was founded in 2008 and it is based in San Francisco, California. On December 10, 2020 the company became public through an IPO, raising $3.5bn. Airbnb decided to go public to gain access to capital markets and fuel growth. The three co-founders were selling 1.9m secondary shares (total shares 51.9m) as an exit option. They will still maintain a 43% voting power after listing. Among the biggest shareholders of Airbnb there are Sequoia Capital and Peter Thiel’s Founder’s Fund. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Allen & Company, BofA Securities, Barclays Capital and Citigroup Global Markets were the main underwriters in the IPO. Total underwriting fees were $74mln (2% of proceeds). The company started trading on Nasdaq Stock Market with the ticker ABNB.

Timing

The travel industry was highly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, and Airbnb registered a loss of $4.5bn in 2020. However, it must be pointed out that the last measure was influenced by charges related to the IPO. Moreover, in May 2020, the company fired almost a quarter of its workforce and market valuation collapsed from $31bn in 2017 to $18bn in that month. The timing for public listing may then appear as wrongly assessed. Nevertheless, Airbnb was able to overcome the market gloom due to its strategic position and projections of future growth. The company exploits indeed a tech-based business model, avoiding costs associated with fixed assets: the risk of payment obligations is hence shifted to homeowners. Another advantage is given by its known brand and loyal customer base. The diffusion of vaccines and end of global lockdowns and restrictions have increased confidence in a prompt return of travels.

Pricing and Market Debut

Shares originally were announced at a price between $44 and $50, with a total implied valuation of $35bn. The range was then revised, due to increasing interest and demand, at $56-$60 per share ($42bn of company value). The final price set was even higher, at $68 per share, implying a valuation of $47bn. At opening, shares were trading at $146, with a 112% increase in a single day. The implied valuation ($86bn) more than doubled the set value. The market capitalization of Airbnb exceeded that of competitors Booking and Expedia. The first day of trading ranked the transaction as the 10th best IPO debut in 2020. Underwriters had the option to allocate 5mln additional shares for a period of 30 days. The greenshoe option ($340m in value) was indeed exercised.

Direct Listing

Overview

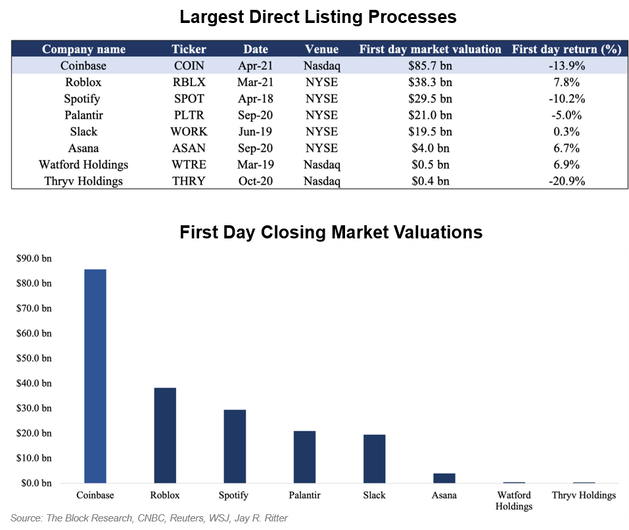

Companies may decide to go public through different methods. One of them, recently experienced by several firms, is the direct listing process (DLP) also known as direct placement or direct public offering (DPO). In such a procedure, companies list their outstanding shares (secondary) on a public exchange without the involvement of financial underwriters. Thus, no new shares (primary) are created, and no new capital is raised in the first place. To be specific, from recent time primary issuance is also allowed increasing the competition to classic IPO alternative. Firms that use DPOs usually look for general benefits of being a public company – such as increased liquidity for existing stockholders – not necessarily seeking capital. Direct listings are not brand-new processes in the financial landscape. However, they have attracted a lot of attention lately. To be precise, market participants started to closely monitor them after the DPOs of Spotify and Slack (respectively in April 2018 and June 2019) and the poor performances of high-profile unicorns’ IPOs such as Uber, Lyft, Peloton, SmileDirect etc. Below, you can find a table reporting the largest direct listings since Spotify, with indications of companies’ first day closing market valuations and first day returns. Furthermore, our last paragraph will be dedicated to the discussion of Coinbase’s direct listing, not only the most recent DPO but also the largest one.

Stabilisation - Greenshoe Option

Underwriters have the right to sell more than the initially planned shares if the demand is higher than expected. Usually, 15% more shares are sold in the market, and within 30 days from the IPO, the underwriting bank may buyback those shares to stabilize the price and support demand. If instead the price of the stock increases, the greenshoe option is exercised and the shares are left in the market, providing extra profit.

Advantages

The first main advantage of an IPO is that it gives the company the possibility to reach a wide and diversified equity base: money is directly collected and can be used for growth or debt repayment. Early investors may also decide to monetize their exposure by selling their shares to the public, exercising an exit option. Shares can also be interpreted as a currency for future acquisitions, facilitating the process. Managers are usually paid with stock options, and this aligns their incentives to the shareholders’ objectives. The new public company gains prestige and exposure and achieves an objective valuation by investment banks. These act as underwriters in the process, bearing the risk that the shares may not be fully allocated. Underwriters may also stabilize the price through the greenshoe option. Usually, a syndicate of banks is created, in order to share the danger of an unsuccessful IPO. Moreover, the book building process is led by investment banks, which allocate together with the company the final shares. Time horizon and strategy of investors are considered, in order to guarantee a liquid secondary market and stability in the market. Indeed, a mixture of institutional investors, retail and hedge funds is involved.

Disadvantages

Primarily, running an IPO is expensive. Companies must bear significant legal, marketing and accounting costs. Investment banks usually receive fees in the range of 1.5% to 5%, depending on the size. In the US fees are higher than in Europe, and in Nordic regions they may even fall below 1%. In particular, Global Coordinators are in charge of overseeing the entire process, Bookrunners are responsible for the pricing, allocation and preparation of documents and Co-Lead Managers support coverage and marketing. Other advisors (legal, audit, specific experts) are required, raising the costs of the process. An IPO requires time and effort by the management of the company, and it may last more than a year from the first internal meetings to the final execution.

Case: Airbnb IPO

Airbnb is an online platform that connects property owners to travelers for lodging. It was founded in 2008 and it is based in San Francisco, California. On December 10, 2020 the company became public through an IPO, raising $3.5bn. Airbnb decided to go public to gain access to capital markets and fuel growth. The three co-founders were selling 1.9m secondary shares (total shares 51.9m) as an exit option. They will still maintain a 43% voting power after listing. Among the biggest shareholders of Airbnb there are Sequoia Capital and Peter Thiel’s Founder’s Fund. Morgan Stanley, Goldman Sachs, Allen & Company, BofA Securities, Barclays Capital and Citigroup Global Markets were the main underwriters in the IPO. Total underwriting fees were $74mln (2% of proceeds). The company started trading on Nasdaq Stock Market with the ticker ABNB.

Timing

The travel industry was highly affected by the Covid-19 pandemic crisis, and Airbnb registered a loss of $4.5bn in 2020. However, it must be pointed out that the last measure was influenced by charges related to the IPO. Moreover, in May 2020, the company fired almost a quarter of its workforce and market valuation collapsed from $31bn in 2017 to $18bn in that month. The timing for public listing may then appear as wrongly assessed. Nevertheless, Airbnb was able to overcome the market gloom due to its strategic position and projections of future growth. The company exploits indeed a tech-based business model, avoiding costs associated with fixed assets: the risk of payment obligations is hence shifted to homeowners. Another advantage is given by its known brand and loyal customer base. The diffusion of vaccines and end of global lockdowns and restrictions have increased confidence in a prompt return of travels.

Pricing and Market Debut

Shares originally were announced at a price between $44 and $50, with a total implied valuation of $35bn. The range was then revised, due to increasing interest and demand, at $56-$60 per share ($42bn of company value). The final price set was even higher, at $68 per share, implying a valuation of $47bn. At opening, shares were trading at $146, with a 112% increase in a single day. The implied valuation ($86bn) more than doubled the set value. The market capitalization of Airbnb exceeded that of competitors Booking and Expedia. The first day of trading ranked the transaction as the 10th best IPO debut in 2020. Underwriters had the option to allocate 5mln additional shares for a period of 30 days. The greenshoe option ($340m in value) was indeed exercised.

Direct Listing

Overview

Companies may decide to go public through different methods. One of them, recently experienced by several firms, is the direct listing process (DLP) also known as direct placement or direct public offering (DPO). In such a procedure, companies list their outstanding shares (secondary) on a public exchange without the involvement of financial underwriters. Thus, no new shares (primary) are created, and no new capital is raised in the first place. To be specific, from recent time primary issuance is also allowed increasing the competition to classic IPO alternative. Firms that use DPOs usually look for general benefits of being a public company – such as increased liquidity for existing stockholders – not necessarily seeking capital. Direct listings are not brand-new processes in the financial landscape. However, they have attracted a lot of attention lately. To be precise, market participants started to closely monitor them after the DPOs of Spotify and Slack (respectively in April 2018 and June 2019) and the poor performances of high-profile unicorns’ IPOs such as Uber, Lyft, Peloton, SmileDirect etc. Below, you can find a table reporting the largest direct listings since Spotify, with indications of companies’ first day closing market valuations and first day returns. Furthermore, our last paragraph will be dedicated to the discussion of Coinbase’s direct listing, not only the most recent DPO but also the largest one.

Process

The direct listing process is quite straightforward. Existing investors, promoters and employees of the company that wants to list can directly sell their shares to the public. Nonetheless, the zero-to-low-cost advantage also comes with risks/uncertainty for the company, which also trickle down to investors (see below a comprehensive recap of the main advantages and disadvantages of the DLP). The firm elect to follow the DLP is required to file a registration statement on Form S-1 (or other applicable registration form) with the SEC (Security and Exchange Commission) at least 15 days in advance of the launch. Upon listing of the firm’s stock, it is subject to the reporting and governance requirements applicable to all publicly traded entities. In particular, it must prepare and issue two disclosure-related annual reports (one sent to the SEC and the other sent to its stockholders) referred to as 10-Ks.

Target Characteristics

Because of the nature and the aim of the direct listing process, there are specific features which make a company a good target for a DPO. To begin with, the firm on its own must be particularly attractive for the market: there are no underwriters assisting the firm and selling its shares. Moreover, the company should be consumer-facing with an effective brand identity, should have a simple and understandable business model and should not be in need of significant additional capital. Taking as two striking examples the direct listings of Spotify and Slack, it should be noted that both of them already had a strong reputation before going public. In addition, they were widely used by customers around the world, and had easy-to-understand monetization/ revenue-generating models. These mentioned characteristics generally increase the number of potential investors in the company as people tend to invest their money in firms that they have heard before, recognize and appreciate.

Advantages

Following our previous discussion, the main pros are to follow:

Disadvantages

Despite their manifold advantages, direct listing processes present some cons and risks to be taken into consideration. The most significant ones are:

Case: Coinbase DPO

Coinbase, the largest cryptocurrency exchange in the US, gone public on April 14, 2021. Following a direct listing process, its shares began to be traded under the ticker “COIN” on the Nasdaq stock exchange. After a briefly overview of Coinbase’s business, we give some specific details about its pricing and market debut.

Coinbase operates as an online exchange, allowing retail buyers and sellers to “meet in the middle” and find a price. Among different digital goods, people can trade Bitcoin, Ripple, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, Ethereum Classic and Litecoin. The company offers to its more experienced users a robust trading platform (“Coinbase Pro”) with a full set of features and charts to help them better investigate the crypto market. Moreover, Coinbase proposes a free wallet service that allows users to safely store their cryptocurrencies. Since its foundation in June 2012 by Brian Armstrong and Fred Ehrsam, it has been succeeding thanks to its high efficiency and security standards (especially compared to similar crypto exchanges which systematically failed to secure their users’ accounts). As of July 2020, Coinbase had more than 35 million users, including both retail clients and institutional firms, up 16.7% from the precedent year. Coinbase does not charge its customers for the storage of cryptocurrencies in its popular wallet service. Instead, it makes money by fees and commissions charged when they actually buy and sell goods. These include a margin fee (spread) and a coinbase fee (in addition to the spread). Besides its exchange services, Coinbase has the following other lines of business: Coinbase Commerce, Coinbase Card, USD Coin (USDC, its own cryptocurrency built on the Ethereum platform and whose value is tied to the US dollar). In FY 2020, the company reported revenues for $1.3bn, more than twice as much as FY 2019.

Pricing and Market Debut

Nasdaq fixed Coinbase shares’ reference price at $250 for a total company valuation of $65 billion. This amount was significantly lower than the estimates related to the tech index trading on the gray market, but still considerably higher than the estimates of end FY 2020. Ultimately, Coinbase Global – the group controlling the exchange – opened at $381 (52.4% above the reference price) and then climbed over $400 throughout the day. At the end, however, the share price lost ground and closed at $328.2 (still higher than the reference price) implying a valuation on a fully diluted basis of $85.7 billion (-13.9% return with respect to the opening price).

SPAC

Overview

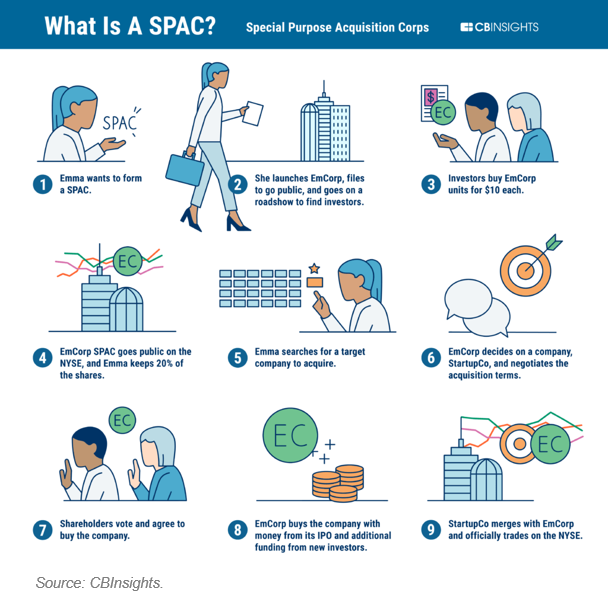

A Special-Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a shell corporation used as an alternative investment vehicle to access capital markets and exists purposefully to raise funds to acquire a target company through a reverse merger and thereby bring it public without the traditional IPO process. Once the SPAC raises the required funds through an IPO, the money is held in a trust until a predetermined period (18-24 months) elapses or the desired acquisition is made. Conversely, in the event that the planned acquisition is not made or legal formalities are still pending, the SPAC is required to return the funds to the investors.

Some other names with which these companies are appointed entail “blank-check” and “shell” companies: the former refers to the idea that investors putting money into these companies typically have no prior idea about what type of business they are investing in, while the latter to the fact that SPACs naturally have no commercial operations when launched.

The founders of a SPAC are its sponsors and they usually include highly-experienced former S&P 500 executives, fund managers or large private equity funds, but it would not be a surprise to see also individuals with no relevant background. For example, some professional athletes who have been involved in SPACs in some capacity include basketball hall of famer Shaquille O’Neal, Golden State Warriors players Steph Curry, tennis champion Serena Williams and former pro baseball player Alex Rodriguez.

Despite the fact that in the 1990s SPACs had a reputation for taking small, immature companies public for a large fee, leading to high levels of company failure and lackluster stock performance at the expense of investors, regulations enacted in the 2000s helped to bring SPACs back into the spotlight, but the financial maneuver lost traction following some high-profile failures in 2008. Following the astonishing growth witnesses in the last couple of years, they are now in fashion more than ever and have become the darling of Wall Street during the Covid-19 pandemic, with 248 companies gone public through mergers with SPACs in 2020, more than last-10-years’ combined. Nevertheless, after SEC warnings of a crackdown, issuance has experienced a remarkable setback in April, with just 10 deals announced this month so far, a 90% drop from March. The slowdown is part of a market response to a looming regulatory crackdown on the overheated SPAC space: during last week, the SEC issued accounting guidance that would classify SPAC warrants as liabilities instead of equity. While not affecting business operation, if it becomes law some SPACs will have to go back and restate their financial results to properly account for warrants, which could slow down their IPO process.

How is a SPAC Created?

The direct listing process is quite straightforward. Existing investors, promoters and employees of the company that wants to list can directly sell their shares to the public. Nonetheless, the zero-to-low-cost advantage also comes with risks/uncertainty for the company, which also trickle down to investors (see below a comprehensive recap of the main advantages and disadvantages of the DLP). The firm elect to follow the DLP is required to file a registration statement on Form S-1 (or other applicable registration form) with the SEC (Security and Exchange Commission) at least 15 days in advance of the launch. Upon listing of the firm’s stock, it is subject to the reporting and governance requirements applicable to all publicly traded entities. In particular, it must prepare and issue two disclosure-related annual reports (one sent to the SEC and the other sent to its stockholders) referred to as 10-Ks.

Target Characteristics

Because of the nature and the aim of the direct listing process, there are specific features which make a company a good target for a DPO. To begin with, the firm on its own must be particularly attractive for the market: there are no underwriters assisting the firm and selling its shares. Moreover, the company should be consumer-facing with an effective brand identity, should have a simple and understandable business model and should not be in need of significant additional capital. Taking as two striking examples the direct listings of Spotify and Slack, it should be noted that both of them already had a strong reputation before going public. In addition, they were widely used by customers around the world, and had easy-to-understand monetization/ revenue-generating models. These mentioned characteristics generally increase the number of potential investors in the company as people tend to invest their money in firms that they have heard before, recognize and appreciate.

Advantages

Following our previous discussion, the main pros are to follow:

- Greater liquidity for existing stockholders and option/RSU holders

- Equal access for all buyers and sellers

- Greater transparency: ability to provide public-company style guidance

- No dilution to existing shareholders; no lock-up restrictions

- Reduced IPO-related documentation (such as the underwriting agreement), no Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA)’s review process

- “Well-trodden” path from an SEC and stock exchange perspective due to Spotify and Slack

Disadvantages

Despite their manifold advantages, direct listing processes present some cons and risks to be taken into consideration. The most significant ones are:

- Opening stock price is completely subject to market demand and potential market swings

- No ability of company and board to set price for shares (only to provide reference price)

- Less control over investors buying shares

- No additional capital raised by the company

- More comprehensive investor education needed (no traditional IPO roadshow to tell story to investors and no research analyst information sharing)

- Direct listing may end up paying more to financial advisors than would have in standard IPO underwriting fees

- Limited in size by the number of shares that company’s employees and existing investors choose to sell on the open market

- Potential to miss out on participation by long-term or large investors as would be typical in an IPO process

- Financial advisors do not plan and participate in investors meetings

- Logistical and communication hurdles in getting shares ready for trading upon listing

- Directors and officers (D&O) liability insurance more expensive

Case: Coinbase DPO

Coinbase, the largest cryptocurrency exchange in the US, gone public on April 14, 2021. Following a direct listing process, its shares began to be traded under the ticker “COIN” on the Nasdaq stock exchange. After a briefly overview of Coinbase’s business, we give some specific details about its pricing and market debut.

Coinbase operates as an online exchange, allowing retail buyers and sellers to “meet in the middle” and find a price. Among different digital goods, people can trade Bitcoin, Ripple, Ethereum, Bitcoin Cash, Ethereum Classic and Litecoin. The company offers to its more experienced users a robust trading platform (“Coinbase Pro”) with a full set of features and charts to help them better investigate the crypto market. Moreover, Coinbase proposes a free wallet service that allows users to safely store their cryptocurrencies. Since its foundation in June 2012 by Brian Armstrong and Fred Ehrsam, it has been succeeding thanks to its high efficiency and security standards (especially compared to similar crypto exchanges which systematically failed to secure their users’ accounts). As of July 2020, Coinbase had more than 35 million users, including both retail clients and institutional firms, up 16.7% from the precedent year. Coinbase does not charge its customers for the storage of cryptocurrencies in its popular wallet service. Instead, it makes money by fees and commissions charged when they actually buy and sell goods. These include a margin fee (spread) and a coinbase fee (in addition to the spread). Besides its exchange services, Coinbase has the following other lines of business: Coinbase Commerce, Coinbase Card, USD Coin (USDC, its own cryptocurrency built on the Ethereum platform and whose value is tied to the US dollar). In FY 2020, the company reported revenues for $1.3bn, more than twice as much as FY 2019.

Pricing and Market Debut

Nasdaq fixed Coinbase shares’ reference price at $250 for a total company valuation of $65 billion. This amount was significantly lower than the estimates related to the tech index trading on the gray market, but still considerably higher than the estimates of end FY 2020. Ultimately, Coinbase Global – the group controlling the exchange – opened at $381 (52.4% above the reference price) and then climbed over $400 throughout the day. At the end, however, the share price lost ground and closed at $328.2 (still higher than the reference price) implying a valuation on a fully diluted basis of $85.7 billion (-13.9% return with respect to the opening price).

SPAC

Overview

A Special-Purpose Acquisition Company (SPAC) is a shell corporation used as an alternative investment vehicle to access capital markets and exists purposefully to raise funds to acquire a target company through a reverse merger and thereby bring it public without the traditional IPO process. Once the SPAC raises the required funds through an IPO, the money is held in a trust until a predetermined period (18-24 months) elapses or the desired acquisition is made. Conversely, in the event that the planned acquisition is not made or legal formalities are still pending, the SPAC is required to return the funds to the investors.

Some other names with which these companies are appointed entail “blank-check” and “shell” companies: the former refers to the idea that investors putting money into these companies typically have no prior idea about what type of business they are investing in, while the latter to the fact that SPACs naturally have no commercial operations when launched.

The founders of a SPAC are its sponsors and they usually include highly-experienced former S&P 500 executives, fund managers or large private equity funds, but it would not be a surprise to see also individuals with no relevant background. For example, some professional athletes who have been involved in SPACs in some capacity include basketball hall of famer Shaquille O’Neal, Golden State Warriors players Steph Curry, tennis champion Serena Williams and former pro baseball player Alex Rodriguez.

Despite the fact that in the 1990s SPACs had a reputation for taking small, immature companies public for a large fee, leading to high levels of company failure and lackluster stock performance at the expense of investors, regulations enacted in the 2000s helped to bring SPACs back into the spotlight, but the financial maneuver lost traction following some high-profile failures in 2008. Following the astonishing growth witnesses in the last couple of years, they are now in fashion more than ever and have become the darling of Wall Street during the Covid-19 pandemic, with 248 companies gone public through mergers with SPACs in 2020, more than last-10-years’ combined. Nevertheless, after SEC warnings of a crackdown, issuance has experienced a remarkable setback in April, with just 10 deals announced this month so far, a 90% drop from March. The slowdown is part of a market response to a looming regulatory crackdown on the overheated SPAC space: during last week, the SEC issued accounting guidance that would classify SPAC warrants as liabilities instead of equity. While not affecting business operation, if it becomes law some SPACs will have to go back and restate their financial results to properly account for warrants, which could slow down their IPO process.

How is a SPAC Created?

The creation of a SPAC begins with a client, being the SPAC originator or initiator and typically the SPAC sponsor as well, who pays the first part of the setup costs and commits to the necessary sponsor capital, also known as skin-in-the-game, which usually account for 7-7.5% of projected IPO size. Setup cost are paid prior to the IPO usually range from 550,000$ to 900,000$, which are likely to be repaid to the SPAC originator afterwards.

If not done already, a SPAC management team needs to be set up, which typically comprises a CEO and a CFO as well as 3 independent directors. Often, SPACs opt for a Chairman as well. The composition of the SPAC board plays an extremely important role in regard of the attractiveness of a SPAC for potential institutional IPO investors.

The SPAC is registered as a company, typically in Delaware or, alternatively, in the BVI, Cayman Islands, depending on their own tax situation.

Auditors, legal counsel and the underwriter (i.e., investment bank, Citigroup, followed by Goldman Sachs, is currently the underwriter with the highest number of SPAC deals completed) are appointed, and the SPAC prospectus is drafted. The company applies to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US for the approval and publishing of the prospectus, referred to as S1: the S1 includes information about the SPAC’s shareholders, board members, size of IPO, cost structure and its acquisition strategy, as well as statutory information.

At this point, the SPAC sponsors provide their sponsor capital, paid on a temporary trust account, being ready for the day of IPO: the sponsor puts in minimal capital (e.g., 25k) and acquires a block of founder stocks, known as the sponsor’s promote, which realistically stand for 3-4% of IPO proceeds but will eventually account for 20% of post-IPO equity.

After the approval of the SPAC prospectus by SEC, the way is paved to approach the right prospective institutional IPO investors during a roadshow. The CEO and the Chairman (if any) of the SPAC and a high-rank member of the underwriting bank are meeting envisaged institutional IPO investors.

The SPAC will be listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ (or other stock exchanges; double listing is also possible) by the underwriting bank. It is now a publicly traded company. Since the company does not do anything (i.e., it has no operational business), the filing process associated with going public is fast and easy. Shares will trade publicly, although there will be little trade volume until first news of possible acquisition targets and respective negotiation is communicated publicly.

During the IPO, the capital is sourced from both retail and institutional investors and 100% of the capital is held in a trust account. In return for their money, investors receive units consisting of a share of common stock, a warrant to purchase stock at a later date and, in some cases, also a right to a fraction of share. The purchase price per unit of the securities is usually $10 and, once the IPO is completed, the units become separable into shares of common stock and warrants, which can be traded in the public market: the purpose of the warrant is to provide investors with additional compensation for investing in the SPAC.

In particular, depending on the bank issuing the IPO and the size of the SPAC, the number of shares that can be purchased with a warrant ranges from 1⁄4 share to one share, with an exercise price uniformly set at $11.50 per share.

Considering the 2019-2020 SPACs that were able to complete their merger, IPO proceeds usually ranged from tens to hundrends of millions of US dollars and, once the funds are collected, they are placed in trust (where there is already the sponsor money) and invested in Treasury notes. Cash in the trust accounts for different functions: acquire the target company, contribute to the capital of the company the SPAC merges with, distribute to shareholders in liquidation if the SPAC fails to complete the merge or redeem shareholders withdrawing their money.

Once the IPO is completed and the proceeds are transferred in the trust account, the SPAC management team screens the market for possible acquisition targets, pursuant to the SPAC’s acquisition strategy as defined in the SPAC prospectus. This step includes proper due diligence and audit of any serious acquisition target company as well as negotiations with the shareholder of the company focused on for acquisition. SPACs can only acquire privately held companies.

A SPAC is required to close the merge within three years of its initial IPO, but SPAC investors typically expect a deal to be closed within 18-24 months. When it is not possibile to close the deal within the established period, the investors get back their money and the special-purpose acquisition company dissolves. In the event of a liquidation, SPAC sponsors lose the money they had invested to found the blank check company.

During the negotiations with the selling shareholders, the SPAC management team has three options to pay for the shares to be acquired. Any combination of those three options is possible as well.

The ideal acquisition would be based on the first option above, because in that case, the IPO-proceeds on trust account could be provided to the company as operation capital, after conclusion of merger. This would also create the best upside momentum for the shareholders.

Once the SPAC management team and the shareholders of the acquisition target company have agreed on the conditions of the acquisition and the merger of the target company into the SPAC, the SPAC shareholders (IPO investors) need to approve the envisaged acquisition.

After the shareholders’ approval, the acquisition takes place and the acquired company will be merged into the SPAC, thus becoming a listed company.

This process is called “business combination”. It is also called “de-SPACing”, as the Special Purpose Acquisition Company is not a SPAC anymore. Typically, the ex SPAC takes the name of the acquired company.

Advantages

Private companies

(1) Share Price: In a typical IPO the company’s share price is uncertain and highly depends on investor appetite and market forces as much as by the company’s underlying business valuation. In addition, the price set by IPO underwriting bankers might not be perfect and the company risks to miss out the possibility of making more money. On the contrary, a SPAC transaction allows the company management team to negotiate an exact purchase price, giving employees and shareholders more certainty.

(2) Fast Process: While the traditional IPO can take years to complete, the SPAC merger process is much faster for the target company, taking as little as 3 to 4 months, which is attractive for companies looking to raise money and go public quickly.

Finally, strategic SPACs use sponsor experience and market knowledge as a selling point.

SPAC sponsors

(1) Huge profits: SPACs are extremely attractive opportunities for sponsors, who stand to make significant amounts of money in most cases. Their biggest challenge is to convince people and funds to invest in their projects: for this reason, most successful SPAC sponsors are likely to be well-known fund managers or highly-experienced executives.

(2) Very low risk: From where it stands now, the sponsors provide about $25,000 to receive 20% of the final company, assuming the deal is completed. Therefore, turning thousand of dollars into millions, their huge profit margin is not particularly impacted if the acquired target company underperforms.

Investors

(1) Institutional investors: For pensions, hedge funds, mutual funds, or investment advisors, SPACs represent a great opportunity mainly as a consequence of the limited risk they face when investing. Indeed, when investors put their money in before the IPO, they receive units containing both shares and warrants, allowing them to buy further shares after the target company is announced at a price slightly higher than the initial one. Moreover, once the acquisition is announced, they also have the right to redeem their shares (but not their warrants) if they are not happy with the target decision, and get their money back if a company is not purchased within 2 years.

(2) Retail investors: Individuals making investments through traditional or online brokerages, who are not allowed to invest in a traditional IPO and therefore have to buy on the open market on the day of trading, are instead invited to the SPACs’ party. Thanks to their structure, SPACs allow retail investors to invest in the time between the IPO and the merger, permitting them to enjoy the “pop” once the business to acquire is announced. Nevertheless, these investors base their choice according to the sponsor, not the private company, which adds risk. Finally, they also are not provided with the rights (enjoyed by institutional investors) that make this structure even more attractive.

Disadvantages

(1) Risk of inappropriate due diligence: sponsors pay very little for a 20% ownership of the SPAC shares, which can result in a huge stake (1-5%) in the acquired company after the merger. Since the sponsors make significant income if the merger is completed, regardless of its outcome, they have no particular incentive to carry out appropriate due diligence on the target company.

(2) Gain for sponsors, loss for target: the stake of the sponsor costs the target company a large portion of equity, which could result in a more expensive deal than a traditional IPO.

(3) Investors’ risk: while institutional investors are able to redeem their shares and get their investment back at the time of the merger announcement, retail investors bear all the risk and really have not much to do in case the sponsor did not do proper due diligence (or chose in bad faith), bringing about an underperforming public company.

(4) Time constraint: owing to the 24-months time constraint and the fact that sponsors lose their money in case of liquidation, if the deadline is approaching, the sponsors may rush to acquire any willing company, which could potentially bring investors to a net loss.

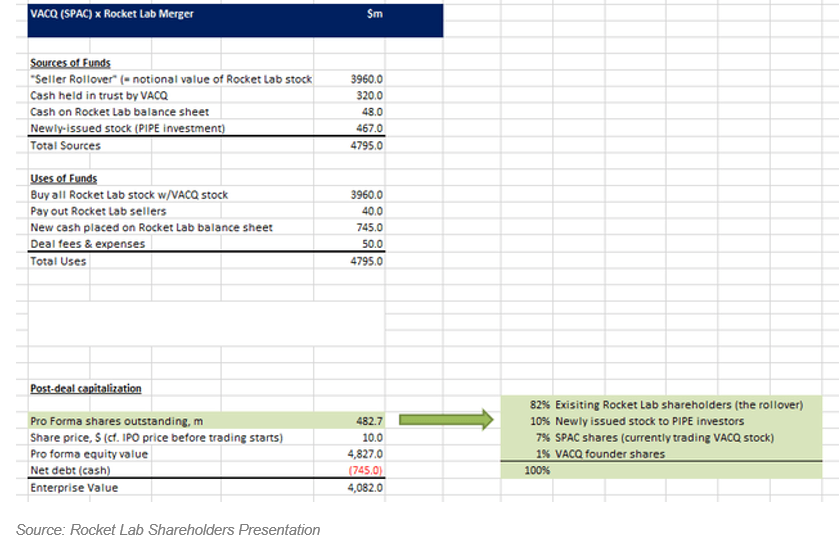

Case: Rocket Lab $4.1 Merger with Vector Capital’s SPAC

Long Beach (CA) headquartered, Rocket Lab USA Inc. is a space-transportation startup and is one of the biggest competitors for SpaceX and Virgin Orbit LLC in the Space systems & Applications space. Besides launching a total of 97 satellites for the government and for private companies for applications including research and communication, Rocket Lab has the second most frequently launched rocket in the US behind SpaceX: with 16 orbital launches since its founding, RockeLab’s flagship rocket Electron is a small rocket that launches satellites and is the only reusable one of its size, allowing saving in production and launch costs. What’s more, Rocket Lab presents a wide network of production and launch facilities across the US and New Zealand. Consequently, Rocket Lab’s products are 90% vertically integrated and are able to produce, reuse, and launch rockets into orbit with little external support.

Vector Acquisition, backed by technology-focused private-equity firm Vector Capital, raised $300m in a September initial public offering by issuing 30 millions units at $10. Each unit consisted of one share of common stock and one-third of a warrant, exercisable at $11.50. The SPAC went public to leverage the management team’s expertise in tech to target technology and tech-services sectors.

Rationale

Through merging with Vector, Rocket Lab expects to use proceeds from the deal to fund development of a medium-lift Neutron launch vehicle tailored for both humans missions and observational satellite launching. In going public, the company can gain more traction compared to competitor SpaceX and continue its innovation by funding the Neutron launch, thus presenting a low-cost alternative to larger vehicles that none of its competitors have crafted. Developing such a vehicle requires significant amounts of capital and merging with a SPAC would be a faster and smoother way to accelerate the process.

In addition, the proceeds can also help enhance organic and inorganic growth, with the former being through simply larger sales and consumer interest from the launch of Neutron and the latter through the managerial assistance the company can get from Vector Corp.

Finally, Rocket Lab will also benefit from its going public to help support acquisition of smaller companies. They had previously acquired Sinclair Interplanetary, a manufacturer of smaller space components, but found the acquisition process challenging due to their status as a private company.

Deal Details

On July 30, 2020, the Sponsor paid $25,000 to cover certain offering costs of the Company in consideration for 8,625,000 Class B ordinary shares (the “Founder Shares”). The Founder Shares include an aggregate of up to 1,125,000 shares that are subject to forfeiture depending on the extent to which the underwriters’ over-allotment option is exercised (i.e., option to issue additional shares), so that the number of Founder Shares will equal, on an as-converted basis, approximately 20% of the Company’s issued and outstanding ordinary shares after the Proposed Public Offering.

Business combination values Rocket Lab at an implied pro forma enterprise value of $4.1bn, representing 5.4x 2025 projected revenue of approximately $750 million

The transaction is expected to result in pro forma cash on the balance sheet of approximately $750m through the contribution of existing cash estimated to be on Rocket Lab’s balance sheet prior to close, up to $320m of cash held in Vector Acquisition Corporation’s trust account (assuming no redemptions by Vector’s public shareholders), and a concurrent approximately $470m PIPE of common stock, priced at $10.00 per share and led by a group of top-tier institutional investors, including Vector Capital, BlackRock and Neuberger Berman, among other 39 investors.

The transaction, which has been unanimously approved by the Boards of Directors of Rocket Lab and Vector, is subject to approval by Vector’s shareholders and other customary closing conditions. Following the closing of the transaction, which is expected be in Q2 2021, upon which Rocket Lab will be publicly listed on the Nasdaq under the ticker RKLB, the Company will continue to be led by Founder and CEO Peter Beck and current Rocket Lab shareholders will own 82% of the pro forma equity of combined company.

If not done already, a SPAC management team needs to be set up, which typically comprises a CEO and a CFO as well as 3 independent directors. Often, SPACs opt for a Chairman as well. The composition of the SPAC board plays an extremely important role in regard of the attractiveness of a SPAC for potential institutional IPO investors.

The SPAC is registered as a company, typically in Delaware or, alternatively, in the BVI, Cayman Islands, depending on their own tax situation.

Auditors, legal counsel and the underwriter (i.e., investment bank, Citigroup, followed by Goldman Sachs, is currently the underwriter with the highest number of SPAC deals completed) are appointed, and the SPAC prospectus is drafted. The company applies to the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in the US for the approval and publishing of the prospectus, referred to as S1: the S1 includes information about the SPAC’s shareholders, board members, size of IPO, cost structure and its acquisition strategy, as well as statutory information.

At this point, the SPAC sponsors provide their sponsor capital, paid on a temporary trust account, being ready for the day of IPO: the sponsor puts in minimal capital (e.g., 25k) and acquires a block of founder stocks, known as the sponsor’s promote, which realistically stand for 3-4% of IPO proceeds but will eventually account for 20% of post-IPO equity.

After the approval of the SPAC prospectus by SEC, the way is paved to approach the right prospective institutional IPO investors during a roadshow. The CEO and the Chairman (if any) of the SPAC and a high-rank member of the underwriting bank are meeting envisaged institutional IPO investors.

The SPAC will be listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ (or other stock exchanges; double listing is also possible) by the underwriting bank. It is now a publicly traded company. Since the company does not do anything (i.e., it has no operational business), the filing process associated with going public is fast and easy. Shares will trade publicly, although there will be little trade volume until first news of possible acquisition targets and respective negotiation is communicated publicly.

During the IPO, the capital is sourced from both retail and institutional investors and 100% of the capital is held in a trust account. In return for their money, investors receive units consisting of a share of common stock, a warrant to purchase stock at a later date and, in some cases, also a right to a fraction of share. The purchase price per unit of the securities is usually $10 and, once the IPO is completed, the units become separable into shares of common stock and warrants, which can be traded in the public market: the purpose of the warrant is to provide investors with additional compensation for investing in the SPAC.

In particular, depending on the bank issuing the IPO and the size of the SPAC, the number of shares that can be purchased with a warrant ranges from 1⁄4 share to one share, with an exercise price uniformly set at $11.50 per share.

Considering the 2019-2020 SPACs that were able to complete their merger, IPO proceeds usually ranged from tens to hundrends of millions of US dollars and, once the funds are collected, they are placed in trust (where there is already the sponsor money) and invested in Treasury notes. Cash in the trust accounts for different functions: acquire the target company, contribute to the capital of the company the SPAC merges with, distribute to shareholders in liquidation if the SPAC fails to complete the merge or redeem shareholders withdrawing their money.

Once the IPO is completed and the proceeds are transferred in the trust account, the SPAC management team screens the market for possible acquisition targets, pursuant to the SPAC’s acquisition strategy as defined in the SPAC prospectus. This step includes proper due diligence and audit of any serious acquisition target company as well as negotiations with the shareholder of the company focused on for acquisition. SPACs can only acquire privately held companies.

A SPAC is required to close the merge within three years of its initial IPO, but SPAC investors typically expect a deal to be closed within 18-24 months. When it is not possibile to close the deal within the established period, the investors get back their money and the special-purpose acquisition company dissolves. In the event of a liquidation, SPAC sponsors lose the money they had invested to found the blank check company.

During the negotiations with the selling shareholders, the SPAC management team has three options to pay for the shares to be acquired. Any combination of those three options is possible as well.

- A share swap where freshly issued SPAC shares are exchanged against the shares of the company to be acquired;

- Cash payment to the shareholders of the private company, to be paid from the IPO proceeds on trust account;

- Asset-backed financing (debt financing where banks lend funds based on the collateral offered by the target company).

The ideal acquisition would be based on the first option above, because in that case, the IPO-proceeds on trust account could be provided to the company as operation capital, after conclusion of merger. This would also create the best upside momentum for the shareholders.

Once the SPAC management team and the shareholders of the acquisition target company have agreed on the conditions of the acquisition and the merger of the target company into the SPAC, the SPAC shareholders (IPO investors) need to approve the envisaged acquisition.

After the shareholders’ approval, the acquisition takes place and the acquired company will be merged into the SPAC, thus becoming a listed company.

This process is called “business combination”. It is also called “de-SPACing”, as the Special Purpose Acquisition Company is not a SPAC anymore. Typically, the ex SPAC takes the name of the acquired company.

Advantages

Private companies

(1) Share Price: In a typical IPO the company’s share price is uncertain and highly depends on investor appetite and market forces as much as by the company’s underlying business valuation. In addition, the price set by IPO underwriting bankers might not be perfect and the company risks to miss out the possibility of making more money. On the contrary, a SPAC transaction allows the company management team to negotiate an exact purchase price, giving employees and shareholders more certainty.

(2) Fast Process: While the traditional IPO can take years to complete, the SPAC merger process is much faster for the target company, taking as little as 3 to 4 months, which is attractive for companies looking to raise money and go public quickly.

Finally, strategic SPACs use sponsor experience and market knowledge as a selling point.

SPAC sponsors

(1) Huge profits: SPACs are extremely attractive opportunities for sponsors, who stand to make significant amounts of money in most cases. Their biggest challenge is to convince people and funds to invest in their projects: for this reason, most successful SPAC sponsors are likely to be well-known fund managers or highly-experienced executives.

(2) Very low risk: From where it stands now, the sponsors provide about $25,000 to receive 20% of the final company, assuming the deal is completed. Therefore, turning thousand of dollars into millions, their huge profit margin is not particularly impacted if the acquired target company underperforms.

Investors

(1) Institutional investors: For pensions, hedge funds, mutual funds, or investment advisors, SPACs represent a great opportunity mainly as a consequence of the limited risk they face when investing. Indeed, when investors put their money in before the IPO, they receive units containing both shares and warrants, allowing them to buy further shares after the target company is announced at a price slightly higher than the initial one. Moreover, once the acquisition is announced, they also have the right to redeem their shares (but not their warrants) if they are not happy with the target decision, and get their money back if a company is not purchased within 2 years.

(2) Retail investors: Individuals making investments through traditional or online brokerages, who are not allowed to invest in a traditional IPO and therefore have to buy on the open market on the day of trading, are instead invited to the SPACs’ party. Thanks to their structure, SPACs allow retail investors to invest in the time between the IPO and the merger, permitting them to enjoy the “pop” once the business to acquire is announced. Nevertheless, these investors base their choice according to the sponsor, not the private company, which adds risk. Finally, they also are not provided with the rights (enjoyed by institutional investors) that make this structure even more attractive.

Disadvantages

(1) Risk of inappropriate due diligence: sponsors pay very little for a 20% ownership of the SPAC shares, which can result in a huge stake (1-5%) in the acquired company after the merger. Since the sponsors make significant income if the merger is completed, regardless of its outcome, they have no particular incentive to carry out appropriate due diligence on the target company.

(2) Gain for sponsors, loss for target: the stake of the sponsor costs the target company a large portion of equity, which could result in a more expensive deal than a traditional IPO.

(3) Investors’ risk: while institutional investors are able to redeem their shares and get their investment back at the time of the merger announcement, retail investors bear all the risk and really have not much to do in case the sponsor did not do proper due diligence (or chose in bad faith), bringing about an underperforming public company.

(4) Time constraint: owing to the 24-months time constraint and the fact that sponsors lose their money in case of liquidation, if the deadline is approaching, the sponsors may rush to acquire any willing company, which could potentially bring investors to a net loss.

Case: Rocket Lab $4.1 Merger with Vector Capital’s SPAC

Long Beach (CA) headquartered, Rocket Lab USA Inc. is a space-transportation startup and is one of the biggest competitors for SpaceX and Virgin Orbit LLC in the Space systems & Applications space. Besides launching a total of 97 satellites for the government and for private companies for applications including research and communication, Rocket Lab has the second most frequently launched rocket in the US behind SpaceX: with 16 orbital launches since its founding, RockeLab’s flagship rocket Electron is a small rocket that launches satellites and is the only reusable one of its size, allowing saving in production and launch costs. What’s more, Rocket Lab presents a wide network of production and launch facilities across the US and New Zealand. Consequently, Rocket Lab’s products are 90% vertically integrated and are able to produce, reuse, and launch rockets into orbit with little external support.

Vector Acquisition, backed by technology-focused private-equity firm Vector Capital, raised $300m in a September initial public offering by issuing 30 millions units at $10. Each unit consisted of one share of common stock and one-third of a warrant, exercisable at $11.50. The SPAC went public to leverage the management team’s expertise in tech to target technology and tech-services sectors.

Rationale

Through merging with Vector, Rocket Lab expects to use proceeds from the deal to fund development of a medium-lift Neutron launch vehicle tailored for both humans missions and observational satellite launching. In going public, the company can gain more traction compared to competitor SpaceX and continue its innovation by funding the Neutron launch, thus presenting a low-cost alternative to larger vehicles that none of its competitors have crafted. Developing such a vehicle requires significant amounts of capital and merging with a SPAC would be a faster and smoother way to accelerate the process.

In addition, the proceeds can also help enhance organic and inorganic growth, with the former being through simply larger sales and consumer interest from the launch of Neutron and the latter through the managerial assistance the company can get from Vector Corp.

Finally, Rocket Lab will also benefit from its going public to help support acquisition of smaller companies. They had previously acquired Sinclair Interplanetary, a manufacturer of smaller space components, but found the acquisition process challenging due to their status as a private company.

Deal Details

On July 30, 2020, the Sponsor paid $25,000 to cover certain offering costs of the Company in consideration for 8,625,000 Class B ordinary shares (the “Founder Shares”). The Founder Shares include an aggregate of up to 1,125,000 shares that are subject to forfeiture depending on the extent to which the underwriters’ over-allotment option is exercised (i.e., option to issue additional shares), so that the number of Founder Shares will equal, on an as-converted basis, approximately 20% of the Company’s issued and outstanding ordinary shares after the Proposed Public Offering.

Business combination values Rocket Lab at an implied pro forma enterprise value of $4.1bn, representing 5.4x 2025 projected revenue of approximately $750 million

The transaction is expected to result in pro forma cash on the balance sheet of approximately $750m through the contribution of existing cash estimated to be on Rocket Lab’s balance sheet prior to close, up to $320m of cash held in Vector Acquisition Corporation’s trust account (assuming no redemptions by Vector’s public shareholders), and a concurrent approximately $470m PIPE of common stock, priced at $10.00 per share and led by a group of top-tier institutional investors, including Vector Capital, BlackRock and Neuberger Berman, among other 39 investors.

The transaction, which has been unanimously approved by the Boards of Directors of Rocket Lab and Vector, is subject to approval by Vector’s shareholders and other customary closing conditions. Following the closing of the transaction, which is expected be in Q2 2021, upon which Rocket Lab will be publicly listed on the Nasdaq under the ticker RKLB, the Company will continue to be led by Founder and CEO Peter Beck and current Rocket Lab shareholders will own 82% of the pro forma equity of combined company.

Alessandro Maraldi

Mattia Baroni

Riccardo Locatelli

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.