INTRODUCTION

European banks play a key role in financial markets: they are an important channel through which the ECB aims to ease lending conditions in the real economy to ensure that households and enterprises have access to credit. This is demonstrated by the importance attributed by the ECB to PELTRO (Pandemic Emergency Longer Term Refinancing Operation) and the TLTRO (Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operation) schemes. The first part of the article will cover the main monetary policy decisions taken by the ECB in the last twelve months and explain the tangible effects on banks’ profitability triggered by the regime of low growth and low rates in the Eurozone. Following this, we will deepen the other main threats to the performance of the banking sector: NPLs, the risks arising from the digitalization of the industry, regulatory overload and shadow banking.

ECB’ S MONETARY POLICY

At the ECB’s annual forum on Central Banking (November 2020), held online for the first time in its history, Christine Lagarde, along with other top central bankers including Jerome Powell (Federal Reserve) and Andrew Bailey (Bank of England), reflected on the results achieved since the outbreak of the Pandemic and on the key challenges that are still ahead. Most importantly, the French policymaker firmly confirmed the ECB’s commitment to making full use of its available range of tools to control financing costs and sent the bloc’s Members a clear invitation to foster the adoption of both “ambitious and realistic” public policies to support economic activity until vaccination is at an advanced stage and can be rolled out on a large scale.

Six months have passed since Lagarde’s highly criticized remark that it was not the ECB’s role to “close spreads”- referring to the widening gap between Italian BTP and the German Bund, a key gauge of Italian sovereign debt risk. Apparently, these few words sufficed to trigger a sell-off in the European bond market and the biggest single-day jump in the yield on Italian 10-year bonds. Nevertheless, she quickly apologized for this unexpected communication and, after that highly discussed episode, deployed the ECB’s monetary policy toolkit to provide a robust response to the crisis. At the last policy meeting, held on December 10, the Governing Council recalibrated its monetary policy instruments with a view to counteract the economic fallout triggered by the resurgence of cases in the continent. Nevertheless, President Lagarde has made it clear that further cooperation between European policymakers, especially on the fiscal side, is pivotal to lead the EU out of economic distress.

The purpose of this article is to go back in time and provide a clear overview of the ECB’s intervention, starting from the few months that preceded the spread of the virus in the European continent up to the last projections released by Lagarde on December 10.

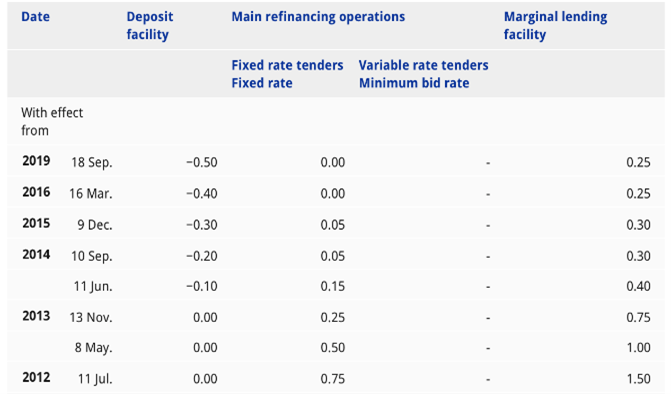

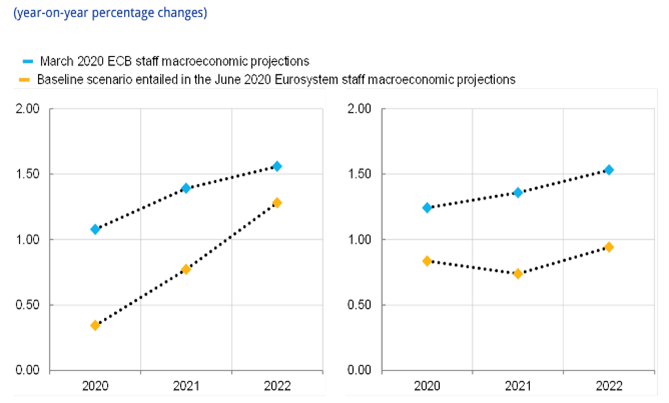

To this end, it is opportune to go through the monetary policy instruments available to the ECB, their intended results, scope of application and functioning. The ECB implements its monetary policy decisions through interest rate setting: the Governing Council sets the official interest rates for the main refinancing operations (MROs), the deposit facility and the marginal lending facility. Changes in the main policy rates (fig.1) have been key measures put forward by central banks to maintain price stability and steer the economy to the targeted level of inflation (e.i. the well-known “lower, but close to 2%” inflation rate for the medium term in the EU, fig.2). Nevertheless, the available space to renew such “conventional measures” of monetary policy for the ECB has been almost entirely used up during Draghi’s mandate. This constraint on the policy toolkit had been already widely recognized by the ECB’s Governing Council in Q419, a time at which the world “pandemic” was only in the mouth of science and history professors. Standard monetary policy measures further include MROs, one-week long liquidity-providing transactions directed to credit institutions, and Longer-Term Refinancing Operations, or LTRO, whose purpose is to inject in the Eurozone additional low-interest rate funding with a three-month maturity.

European banks play a key role in financial markets: they are an important channel through which the ECB aims to ease lending conditions in the real economy to ensure that households and enterprises have access to credit. This is demonstrated by the importance attributed by the ECB to PELTRO (Pandemic Emergency Longer Term Refinancing Operation) and the TLTRO (Targeted Longer Term Refinancing Operation) schemes. The first part of the article will cover the main monetary policy decisions taken by the ECB in the last twelve months and explain the tangible effects on banks’ profitability triggered by the regime of low growth and low rates in the Eurozone. Following this, we will deepen the other main threats to the performance of the banking sector: NPLs, the risks arising from the digitalization of the industry, regulatory overload and shadow banking.

ECB’ S MONETARY POLICY

At the ECB’s annual forum on Central Banking (November 2020), held online for the first time in its history, Christine Lagarde, along with other top central bankers including Jerome Powell (Federal Reserve) and Andrew Bailey (Bank of England), reflected on the results achieved since the outbreak of the Pandemic and on the key challenges that are still ahead. Most importantly, the French policymaker firmly confirmed the ECB’s commitment to making full use of its available range of tools to control financing costs and sent the bloc’s Members a clear invitation to foster the adoption of both “ambitious and realistic” public policies to support economic activity until vaccination is at an advanced stage and can be rolled out on a large scale.

Six months have passed since Lagarde’s highly criticized remark that it was not the ECB’s role to “close spreads”- referring to the widening gap between Italian BTP and the German Bund, a key gauge of Italian sovereign debt risk. Apparently, these few words sufficed to trigger a sell-off in the European bond market and the biggest single-day jump in the yield on Italian 10-year bonds. Nevertheless, she quickly apologized for this unexpected communication and, after that highly discussed episode, deployed the ECB’s monetary policy toolkit to provide a robust response to the crisis. At the last policy meeting, held on December 10, the Governing Council recalibrated its monetary policy instruments with a view to counteract the economic fallout triggered by the resurgence of cases in the continent. Nevertheless, President Lagarde has made it clear that further cooperation between European policymakers, especially on the fiscal side, is pivotal to lead the EU out of economic distress.

The purpose of this article is to go back in time and provide a clear overview of the ECB’s intervention, starting from the few months that preceded the spread of the virus in the European continent up to the last projections released by Lagarde on December 10.

To this end, it is opportune to go through the monetary policy instruments available to the ECB, their intended results, scope of application and functioning. The ECB implements its monetary policy decisions through interest rate setting: the Governing Council sets the official interest rates for the main refinancing operations (MROs), the deposit facility and the marginal lending facility. Changes in the main policy rates (fig.1) have been key measures put forward by central banks to maintain price stability and steer the economy to the targeted level of inflation (e.i. the well-known “lower, but close to 2%” inflation rate for the medium term in the EU, fig.2). Nevertheless, the available space to renew such “conventional measures” of monetary policy for the ECB has been almost entirely used up during Draghi’s mandate. This constraint on the policy toolkit had been already widely recognized by the ECB’s Governing Council in Q419, a time at which the world “pandemic” was only in the mouth of science and history professors. Standard monetary policy measures further include MROs, one-week long liquidity-providing transactions directed to credit institutions, and Longer-Term Refinancing Operations, or LTRO, whose purpose is to inject in the Eurozone additional low-interest rate funding with a three-month maturity.

Fig 1: Main policy rates since July 2012, source: www.ecb.europa.ue

Fig 2(left): Projected euro area headline inflation and headline inflation excluding food and energy, source: www.ecb.europa.u

Fig 2(left): Projected euro area headline inflation and headline inflation excluding food and energy, source: www.ecb.europa.u

In the pre-Covid-19 era, to foster favorable credit conditions for banks and support money market activity, the ECB introduced Targeted Longer-Term Financing Operations with maturities longer than one year. The first programme TLTRO I was launched in 2014 and was later followed by TLTRO II, announced in March 2016. Both programmes ended in 2017. In March 2019, the Governing Council announced the launch of a new series of quarterly targeted long term refinancing operations (TLTRO III). The actual operations started in September 2019, and have a maturity of two years. In TLTRO III, as with the previous one, the amount of financing banks receive depends on their lending patterns to non-financial corporations and households (lending performance). The more loans they make the more favorable the conditions under which they receive financing from the ECB will be. On this occasion, the actual amount that banks can borrow from the ECB, known as borrowing allowance, was raised to 50% of their stock of eligible loans made to firms and households.

Another fundamental component of the package of “non-standard policy measures” is the Asset Purchase Programme. The programme was initiated between 2014 and 2015 when the risk of prolonged inflation following the Sovereign Debt Crisis was threatening the Euro system and the interest rate on the deposit facility was already below the Zero Lower Bound, a sluggishness in the economy very similar to what we are facing today. The APP was subdivided into distinct operations according to the specific type of security purchased by the ECB (government debt, corporate debt, banks’ covered bonds or asset-backed securities). By expanding its balance sheet through the purchase of longer-term securities, this program allows the ECB to expand the supply of money, increase investment and push inflation without going through further rate cutting. The APP corresponds to a European version of quantitative easing, a large-scale purchase of assets implemented by several other central banks. This monetary policy tool was first adopted by the Bank of Japan in 2001 to fight the deflationary trap and rock-bottom economic growth affecting the country since the beginning of the 90s. However, the enormous support provided by the BOJ through ultra-loose monetary policy failed to spur productivity growth in the country and save it from stagnation. As a matter of fact, the world of low growth, ultra-loose monetary policy and deflation that persistently plague the Japanese economy led scholars to theorize the economics of “Japanification”. An expansion of this regime to other advanced economies such the U.S. and the EU is now one of the hottest topics in economic research and one of the most threatening scenarios for Western Governments and lending institutions.

The economic and financial distress triggered by the health emergency set a new and unprecedented challenge that warranted a vigorous policy response by the ECB. Indeed, ensuring a smooth transmission of monetary policy decisions is fundamental to reduce the impact of the (likely) structural changes that the European Economy is undergoing and ensure financial institutions are in the right conditions to provide support to businesses and households. Consequently, the ECB was forced to expand its existing policy toolkit to include new monetary policy instruments that were specifically designed and are constantly revisited to counteract the current crisis.

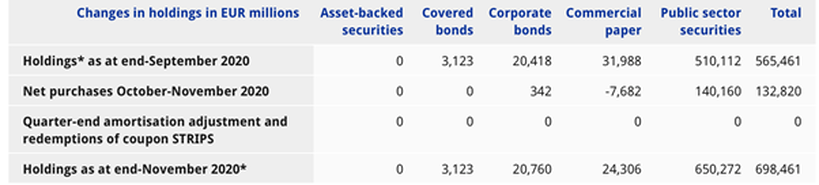

On March 18th, while European governments were shutting down the large majority of their economic activities, the ECB announced a new bond-buying programme, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). This temporary programme included the purchase of both public and private securities and was initially earmarked €750 billion. This amount was later increased by €600 bn to reach a total of €1,350 billion. The most up-to-date revision was announced on December 10 and consisted in a €500bn expansion of the programme’s budget and its extension to March 2022. The eligible securities for the PEPP include not only asset categories that fall under the APP but also securities issued by the Greek government and non-financial commercial papers (namely short-term promissory notes issued by non-financial firms). As regards the purchase of public sector securities, the criteria of allocation of the PEPP across different Member States depends on the percentage of capital held by each national central bank at the ECB (known as “capital key”).

As of 4 December 2020, the total holdings of the BCE amount to approximately €717,918 billion.

Another fundamental component of the package of “non-standard policy measures” is the Asset Purchase Programme. The programme was initiated between 2014 and 2015 when the risk of prolonged inflation following the Sovereign Debt Crisis was threatening the Euro system and the interest rate on the deposit facility was already below the Zero Lower Bound, a sluggishness in the economy very similar to what we are facing today. The APP was subdivided into distinct operations according to the specific type of security purchased by the ECB (government debt, corporate debt, banks’ covered bonds or asset-backed securities). By expanding its balance sheet through the purchase of longer-term securities, this program allows the ECB to expand the supply of money, increase investment and push inflation without going through further rate cutting. The APP corresponds to a European version of quantitative easing, a large-scale purchase of assets implemented by several other central banks. This monetary policy tool was first adopted by the Bank of Japan in 2001 to fight the deflationary trap and rock-bottom economic growth affecting the country since the beginning of the 90s. However, the enormous support provided by the BOJ through ultra-loose monetary policy failed to spur productivity growth in the country and save it from stagnation. As a matter of fact, the world of low growth, ultra-loose monetary policy and deflation that persistently plague the Japanese economy led scholars to theorize the economics of “Japanification”. An expansion of this regime to other advanced economies such the U.S. and the EU is now one of the hottest topics in economic research and one of the most threatening scenarios for Western Governments and lending institutions.

The economic and financial distress triggered by the health emergency set a new and unprecedented challenge that warranted a vigorous policy response by the ECB. Indeed, ensuring a smooth transmission of monetary policy decisions is fundamental to reduce the impact of the (likely) structural changes that the European Economy is undergoing and ensure financial institutions are in the right conditions to provide support to businesses and households. Consequently, the ECB was forced to expand its existing policy toolkit to include new monetary policy instruments that were specifically designed and are constantly revisited to counteract the current crisis.

On March 18th, while European governments were shutting down the large majority of their economic activities, the ECB announced a new bond-buying programme, the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Programme (PEPP). This temporary programme included the purchase of both public and private securities and was initially earmarked €750 billion. This amount was later increased by €600 bn to reach a total of €1,350 billion. The most up-to-date revision was announced on December 10 and consisted in a €500bn expansion of the programme’s budget and its extension to March 2022. The eligible securities for the PEPP include not only asset categories that fall under the APP but also securities issued by the Greek government and non-financial commercial papers (namely short-term promissory notes issued by non-financial firms). As regards the purchase of public sector securities, the criteria of allocation of the PEPP across different Member States depends on the percentage of capital held by each national central bank at the ECB (known as “capital key”).

As of 4 December 2020, the total holdings of the BCE amount to approximately €717,918 billion.

Figure 3: Eurosystem holdings under the PEPP by asset category. Source: European Central Bank

As this article deals with the topic of bank profitability, we should dedicate greater attention to the ECB action to establish cheap credit lines with European banks and, in turn, make sure firms and households could have access to lending. In April 2020, the Governing Council approved a recalibration on the third series of Targeted Longer Term Financing Operations (TLTRO III) consisting of a cut of the interest rate on these operations by 25 bp to -0.5% for the period between 24 June 2020 and 23 June 2021 and a rise in the borrowing allowance to 50% of the bank’s stock of eligible loans. Further to this, the ECB relaxed the threshold of lending performance (see above TLTRO) over which banks are subjected to cheaper loans at -1% interest rate. On 30 April 2020, the ECB announced its intention to provide banks with new fresh lending through the Pandemic Emergency Longer Term Refinancing Operations. The new PELTROs are launched monthly and are supposed to last until next year to serve as an effective liquidity backstop in the Eurozone. The interest rate on these operations can be as low as -0.25%. On December 10, the Governing Council announced the decision to lengthen the period of extremely favorable lending conditions for banks by 12 months to June 2022. In fact, alongside the boost to its bond-buying programme, the ECB said it will offer three additional three-year targeted lending operations in June, September and December 2021. Importantly, the borrowing allowance was raised to 55% in order to bolster the incentive mechanism for lending institutions and facilitate the flow of financing to the real economy.

To sum up, it is clear that the ECB’s strategy has targeted three main objectives: market stabilization and smooth monetary policy transmission across the euro area, prevention of the emergence of liquidity shortages in the real economy and preservation of the accommodative (probably ultra-accommodative) stance of monetary policy.

During her last press-conference, Lagarde highlighted how inflation in the Eurozone is “disappointingly low” as it is projected to reach 1.1% by 2022 and remains immensely below the aforementioned target. Other concerns point to the lack of agreement and full cooperation between the Governing Council members forcing the President to reach compromise between multiple parties and preventing her from deploying the ECB toolkit at its fullest. This is why many have referred to the last monetary policy decision as a “holding operation” that simply expanded existing instruments but failed to address issues such as the rise of the Euro against the dollar. This confirms the point that the ECB is increasingly relying on stronger intervention by other European policymakers to come to the rescue of the economy.

During her last press-conference, Lagarde highlighted how inflation in the Eurozone is “disappointingly low” as it is projected to reach 1.1% by 2022 and remains immensely below the aforementioned target. Other concerns point to the lack of agreement and full cooperation between the Governing Council members forcing the President to reach compromise between multiple parties and preventing her from deploying the ECB toolkit at its fullest. This is why many have referred to the last monetary policy decision as a “holding operation” that simply expanded existing instruments but failed to address issues such as the rise of the Euro against the dollar. This confirms the point that the ECB is increasingly relying on stronger intervention by other European policymakers to come to the rescue of the economy.

FACTORS UNDERLYING THE UNDERPERFORMING OF THE BANKING SECTOR

LOW INTEREST RATES

The logic behind a loose monetary policy is that lowering interest rates raises banks’ returns from loans relative to other investments, as funding costs tend to fall faster than lending rates. As result, theory suggests that banks would respond to lower monetary policy rates by expanding lending to businesses and households. However, when rates are around the Zero Lower Bound, or even entry into negative territory, banks become reluctant to push rates on retail deposits below zero. Indeed, looking at some Euro area interest rates statistics as of January 2020, the composite cost-of-borrowing indicator for new loans for corporations showed no change at 1.55%, while the one for new loans to households for house purchase remained broadly unchanged at 1.44%. The euro area composite interest rate for new deposits with agreed maturity from households increased by 4 basis points to 0.32% in January 2020, and the interest rate for overnights deposits from households remained broadly unchanged at 0.02%.

The logic behind a loose monetary policy is that lowering interest rates raises banks’ returns from loans relative to other investments, as funding costs tend to fall faster than lending rates. As result, theory suggests that banks would respond to lower monetary policy rates by expanding lending to businesses and households. However, when rates are around the Zero Lower Bound, or even entry into negative territory, banks become reluctant to push rates on retail deposits below zero. Indeed, looking at some Euro area interest rates statistics as of January 2020, the composite cost-of-borrowing indicator for new loans for corporations showed no change at 1.55%, while the one for new loans to households for house purchase remained broadly unchanged at 1.44%. The euro area composite interest rate for new deposits with agreed maturity from households increased by 4 basis points to 0.32% in January 2020, and the interest rate for overnights deposits from households remained broadly unchanged at 0.02%.

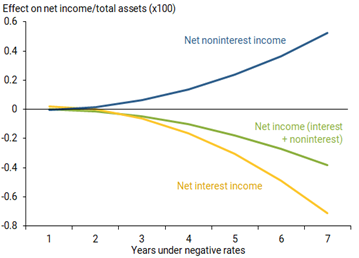

Source: Fed Economic research (28/09/2020

Banks can only mitigate losses on interest income by charging fees on deposits. They might be also able to enjoy some capital gains on some fixed income holdings if negative interest rates are short-lived. For instance, the chart shows the impact of negative interest rates on banks’ profitability as a function of time: losses on interest income accelerate over time and, eventually, begin to outweigh the gains from non-interest income. In conclusion, as years under negative rates increase, the gains from noninterest income become increasingly inadequate to offset losses on interest income: this happens because of banks’ limited abilities to pass along negative rates to depositors. The result is that, as negative rates persist, they drag on bank profitability even more.

INCREASE OF THE NPL IN THE BANKING INDUSTRY

NPL, which stands for Non-Performing Loan, is an impaired loan towards either corporate companies or individuals. After the 2008 financial crisis, NPL turnover increased for several years, largely due to the economic crunch that followed, but also due to illegal or inadequate credit supply activities, which resulted in sanctions and financial inquiries.

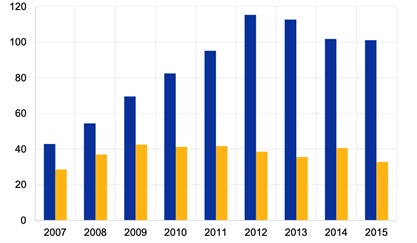

According to the annual reports of the ECB, the total value of the NPLs has decreased since its peak in 2012, following the economic rebound. However, due to the Covid-19 crisis, the trend seems to have inverted dramatically: last month, the ECB’s top bank supervisor Andrea Enria wrote that, in a “severe but plausible” scenario, non-performing loans at eurozone banks could reach €1.4tn, well above the levels of the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing EU sovereign debt crisis.

INCREASE OF THE NPL IN THE BANKING INDUSTRY

NPL, which stands for Non-Performing Loan, is an impaired loan towards either corporate companies or individuals. After the 2008 financial crisis, NPL turnover increased for several years, largely due to the economic crunch that followed, but also due to illegal or inadequate credit supply activities, which resulted in sanctions and financial inquiries.

According to the annual reports of the ECB, the total value of the NPLs has decreased since its peak in 2012, following the economic rebound. However, due to the Covid-19 crisis, the trend seems to have inverted dramatically: last month, the ECB’s top bank supervisor Andrea Enria wrote that, in a “severe but plausible” scenario, non-performing loans at eurozone banks could reach €1.4tn, well above the levels of the 2008 financial crisis and the ensuing EU sovereign debt crisis.

The ratio between the total amount of the NPL and the sum of Net capital and tangible assets of EU banking groups. The blue lines represent the countries most affected by the financial crisis and the yellow lines all other countries. Source: ECB NPL guidelines report

The main issues of NPLs that affects banking profitability are:

Therefore, the impact of NPLs on the banks’ Net Income is significant because it affects both Net Capital and the regulatory capital. These policies, considering also the current low interest rate environment, resulting in a banking sector full of liquidity that cannot be used.

DIGITALIZATION OF THE BANKING SECTOR

The digitization process of financial services was already disrupting the banking industry before Covid-19, forcing banks to close branches and dismiss personnel. Now, social distancing and lockdowns have caused a strong acceleration of this process, but what are the consequences?

Digitalization, especially for the large traditional banks, brings three fundamental challenges that the banking sector must face. First, social issues connected to staff reduction and transformation. Second, there is a problem connected to real estate: usually, banks used to carry out their activities in expensive buildings situated in city centers. With the Covid-19 outbreak some of these buildings became non-performing assets that cannot be liquidated in the short term. Finally, the cost structure of the banking sector is becoming more and more rigid with a significant increase in IT expenses (in Italy, the total amount of IT expenses this year has been 4.9 billion). This is happening because competitors, in a negative interest rate environment, are betting more and more on operating efficiency to boost profitability.

In particular, fintech has been gaining importance over the last decade. Indeed, innovative capacity and low costs (thanks to digital banking) of the firms operating in the sector can provide customers the same service (sometimes even improved with new functionalities) that traditional banks offer. Additionally, fintech players tend to have a lighter cost structure and they are subjected to a looser regulation. In this way, they are able to hamper traditional financial institutions and bring customers towards this innovative sector.

REGULATION

Over the last decades, the banking sector has been subject to stricter regulation. This was not a result of a detailed and planned blueprint, but, especially in the US, of a set of accumulated responses to a long series of financial crises and scandals.

The Basel Committee played a central role in establishing the framework for a uniform and international banking regulation. This international organization - initially named the Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practices - was established in 1974 by the central bank Governors of Ten Countries after a series of issues in international currency and banking markets.

Ensuring harmonization and reducing asymmetries in international banking, the Basel Committee was the result of the commitment of close international cooperation among banking supervisors. Since its foundation, the institution has published four sets of standards for the banking frameworks, starting from Basel I, which introduced the requirement to maintain a minimum of 8% of Capital to Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs) Ratio. Agreed in 2017 and due to implementation in 2023, Basel IV standards are the international authority’s latest measures, which are aimed once again at ensuring safeness in financial systems, at the expense however of banks’ profitability, which will need on average €120 billion in additional capital (to comply with the new regulation) and, according to a research conducted by McKinsey, will see sector ROE dropping by 0.6 percentage points. As for any regulatory measure, the establishment of Basel requirements has limited banks’ exercises and hampered financial institutions’ programming activities. Additionally, it has increased banks’ costs necessary to continuously comply with newer regulatory duties.

- Legal and Administrative costs associated with credit recovery and timing of recovery procedures, which is different in each country, but it can go from some weeks to several months (in Italy, the country in which timing of credit recovery is longer, it can take more than one year)

- Equity weighting: Basel agreement fixed a much higher weighting on regulatory capital for the NPLs that banks have to respect (150% on Tier 1-2-3 against a usual 100% weighting for corporate loans and 75% for retail loans) thus significantly limiting investing resources and opportunities that banks can exploit and develop.

- Provisions: for every NPL the bank must put aside a percentage of capital in order to cover the major risk associated with the impaired loan. Moreover, the new DOD (definition of default) guidelines of the ECB that will be introduced at the beginning of 2021 will force banks to cover 30% of their position for each NPL with a duration of less than 2 years and 100% of their position for each NPL with a duration of more than 3 years.

Therefore, the impact of NPLs on the banks’ Net Income is significant because it affects both Net Capital and the regulatory capital. These policies, considering also the current low interest rate environment, resulting in a banking sector full of liquidity that cannot be used.

DIGITALIZATION OF THE BANKING SECTOR

The digitization process of financial services was already disrupting the banking industry before Covid-19, forcing banks to close branches and dismiss personnel. Now, social distancing and lockdowns have caused a strong acceleration of this process, but what are the consequences?

Digitalization, especially for the large traditional banks, brings three fundamental challenges that the banking sector must face. First, social issues connected to staff reduction and transformation. Second, there is a problem connected to real estate: usually, banks used to carry out their activities in expensive buildings situated in city centers. With the Covid-19 outbreak some of these buildings became non-performing assets that cannot be liquidated in the short term. Finally, the cost structure of the banking sector is becoming more and more rigid with a significant increase in IT expenses (in Italy, the total amount of IT expenses this year has been 4.9 billion). This is happening because competitors, in a negative interest rate environment, are betting more and more on operating efficiency to boost profitability.

In particular, fintech has been gaining importance over the last decade. Indeed, innovative capacity and low costs (thanks to digital banking) of the firms operating in the sector can provide customers the same service (sometimes even improved with new functionalities) that traditional banks offer. Additionally, fintech players tend to have a lighter cost structure and they are subjected to a looser regulation. In this way, they are able to hamper traditional financial institutions and bring customers towards this innovative sector.

REGULATION

Over the last decades, the banking sector has been subject to stricter regulation. This was not a result of a detailed and planned blueprint, but, especially in the US, of a set of accumulated responses to a long series of financial crises and scandals.

The Basel Committee played a central role in establishing the framework for a uniform and international banking regulation. This international organization - initially named the Committee on Banking Regulations and Supervisory Practices - was established in 1974 by the central bank Governors of Ten Countries after a series of issues in international currency and banking markets.

Ensuring harmonization and reducing asymmetries in international banking, the Basel Committee was the result of the commitment of close international cooperation among banking supervisors. Since its foundation, the institution has published four sets of standards for the banking frameworks, starting from Basel I, which introduced the requirement to maintain a minimum of 8% of Capital to Risk-Weighted Assets (RWAs) Ratio. Agreed in 2017 and due to implementation in 2023, Basel IV standards are the international authority’s latest measures, which are aimed once again at ensuring safeness in financial systems, at the expense however of banks’ profitability, which will need on average €120 billion in additional capital (to comply with the new regulation) and, according to a research conducted by McKinsey, will see sector ROE dropping by 0.6 percentage points. As for any regulatory measure, the establishment of Basel requirements has limited banks’ exercises and hampered financial institutions’ programming activities. Additionally, it has increased banks’ costs necessary to continuously comply with newer regulatory duties.

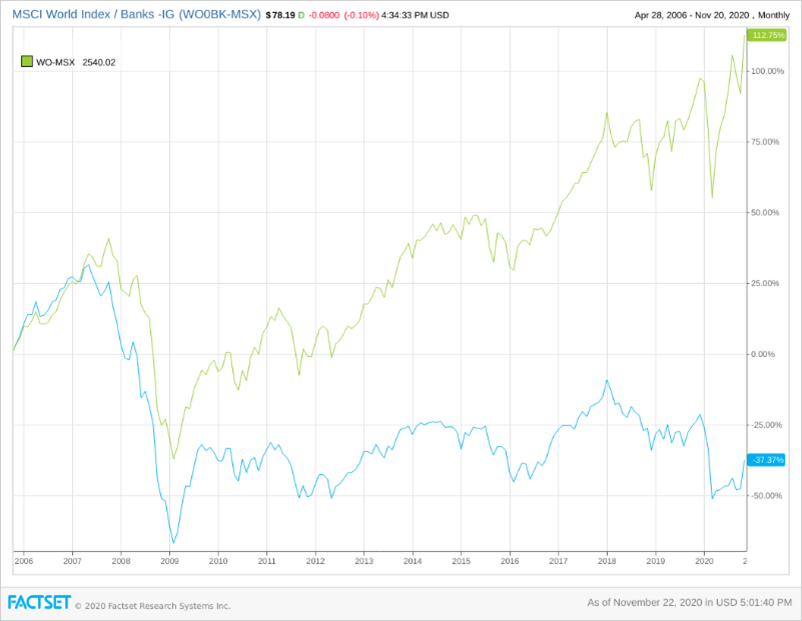

Comparison between the MSCI World Index and MSCI World Bank Index. Source: Factset

So, regulation has negatively impacted banks’ profitability. In fact, the banking industry has greatly underperformed the market in the past 15 years: while the MSCI World Index achieved a cumulative return of 112.75% (a CAGR of 5.16%), the MSCI World Bank Index had a -3.09% average annual return.

SHADOW BANKING

To make matters worse, constrained by the ever-changing regulation, banks face a significant threat to their business model: the existence of financial intermediaries that look and act as banks, except for the fact that they are not banks. They operate in the field that is generally called shadow banking.

Coined for the first time by the economist Paul McCulley in 2007, this term refers to all those credit-creation (more specifically, maturity transformation) activities carried out by unregulated intermediaries that can engage in the process of buying assets with long maturities by raising capital through short-term funds in the money markets.

This process is frequently carried out by institutions like hedge funds, that can escape the burden of regulation by the fact that they do not raise funds from the general public (as opposed to banks, which greatly use customers’ deposits to finance their operations) and hence they are allowed to be exposed to more risk, a crucial element in shadow banking. There is a growing concern around shadow banking, also because it is considered one of the causes of the 2008 financial meltdown.

Shadow banks’ profit-generating activity consists, among other things, of acting as intermediaries between large borrowers and large lenders, earning their revenue from interest rates spreads and the fees they charge for their services. They often use of derivatives such as ABS, REPOs, CDS and other structured securities to extract value from the transaction.

Moreover, regulators are particularly concerned by shadow banks’ growing role in turning home mortgages into securities and their increasing presence in peer-to-peer lending. These activities are both hurting traditional financial intermediaries’ profitability and creating the prerequisites for the possible next financial time bomb.

Overall, shadow banking is a strongly growing sector, with a 2012-17 average annual growth rate of 8.5%, as tracked by the Financial Stability Board. This growth can be interpreted as a consequence of stricter regulation for traditional banks, which are not able to keep up with unregulated competitors. However, shadow banking has the potential to undermine traditional banking and the weakened influence that central banks have on monetary systems.

CONCLUSION

The European banking industry has been underperforming the broader stock market over the last decade. There are several reasons behind this crisis: a monetary policy oriented towards low-interest rates, the advent of digitalization in the sector (which is an advantage for innovative and disruptive start-ups rather than for traditional behemoths), and stricter regulation.

In particular, the last element is the most controversial, given that, although the Basel Committee aimed at ensuring stability in financial markets, regulation ended up hampering bank’s operations and gave fuel to shadow banking, boosting non-bank financing and building up the foundations (who knows) for the next financial crisis.

Article by Andrea Longoni, Francesco Catanzariti, and Matteo Girello.

SHADOW BANKING

To make matters worse, constrained by the ever-changing regulation, banks face a significant threat to their business model: the existence of financial intermediaries that look and act as banks, except for the fact that they are not banks. They operate in the field that is generally called shadow banking.

Coined for the first time by the economist Paul McCulley in 2007, this term refers to all those credit-creation (more specifically, maturity transformation) activities carried out by unregulated intermediaries that can engage in the process of buying assets with long maturities by raising capital through short-term funds in the money markets.

This process is frequently carried out by institutions like hedge funds, that can escape the burden of regulation by the fact that they do not raise funds from the general public (as opposed to banks, which greatly use customers’ deposits to finance their operations) and hence they are allowed to be exposed to more risk, a crucial element in shadow banking. There is a growing concern around shadow banking, also because it is considered one of the causes of the 2008 financial meltdown.

Shadow banks’ profit-generating activity consists, among other things, of acting as intermediaries between large borrowers and large lenders, earning their revenue from interest rates spreads and the fees they charge for their services. They often use of derivatives such as ABS, REPOs, CDS and other structured securities to extract value from the transaction.

Moreover, regulators are particularly concerned by shadow banks’ growing role in turning home mortgages into securities and their increasing presence in peer-to-peer lending. These activities are both hurting traditional financial intermediaries’ profitability and creating the prerequisites for the possible next financial time bomb.

Overall, shadow banking is a strongly growing sector, with a 2012-17 average annual growth rate of 8.5%, as tracked by the Financial Stability Board. This growth can be interpreted as a consequence of stricter regulation for traditional banks, which are not able to keep up with unregulated competitors. However, shadow banking has the potential to undermine traditional banking and the weakened influence that central banks have on monetary systems.

CONCLUSION

The European banking industry has been underperforming the broader stock market over the last decade. There are several reasons behind this crisis: a monetary policy oriented towards low-interest rates, the advent of digitalization in the sector (which is an advantage for innovative and disruptive start-ups rather than for traditional behemoths), and stricter regulation.

In particular, the last element is the most controversial, given that, although the Basel Committee aimed at ensuring stability in financial markets, regulation ended up hampering bank’s operations and gave fuel to shadow banking, boosting non-bank financing and building up the foundations (who knows) for the next financial crisis.

Article by Andrea Longoni, Francesco Catanzariti, and Matteo Girello.