Government Pension Fund of Norway, the largest pension fund in Europe, has been urged by an internal committee to shift 10 percent of its investments from bonds to stock.

The fund, commonly known as “The Oil Fund”, was established in 1990 after a decision by the Parliament of Norway, with the purpose of supporting the government’s long-term management of petroleum revenue, and designed to be invested on the market in a way that enabled the government to tap into when necessary.

The fund, commonly known as “The Oil Fund”, was established in 1990 after a decision by the Parliament of Norway, with the purpose of supporting the government’s long-term management of petroleum revenue, and designed to be invested on the market in a way that enabled the government to tap into when necessary.

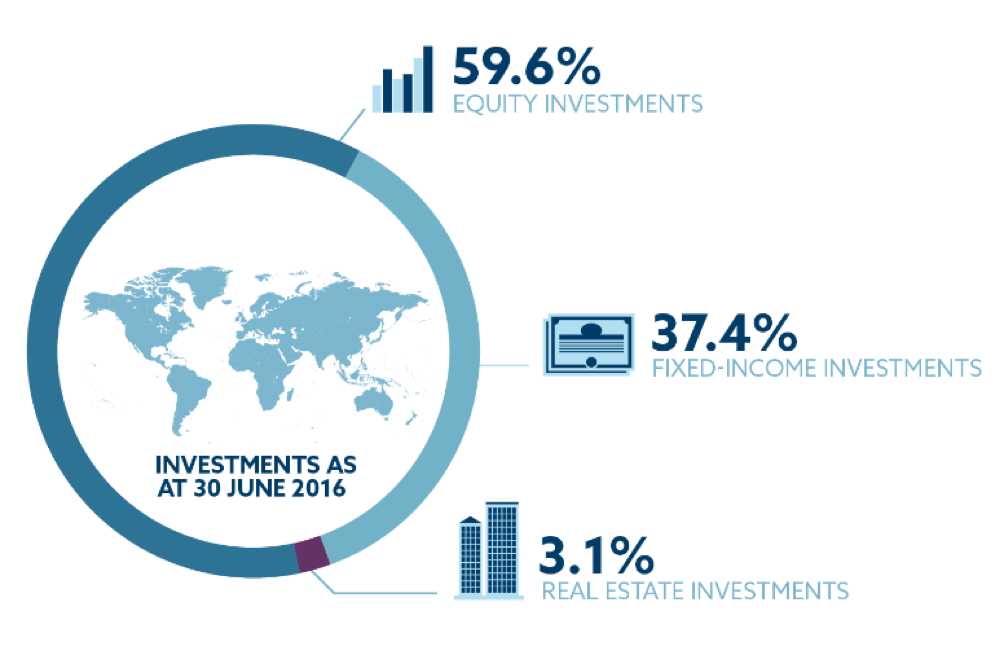

After getting its first capital infusion, the fund has constantly increased its risk profile, widening into stocks in 1998, emerging markets in 2000 and real estate in 2011.

Currently, the Oil Fund owns $875 billion of assets under management, 5 percent of which are invested in real estate, 35 percent in bonds and 60 percent in stocks.

Norway’s government has its real return goal set to 4 percent per year, but this target is getting more and more difficult to hit, given the low return rates of bonds. Indeed, the current assets allocation has returned 3.43 percent over the past 10 years and esteems expect the current return to drop to only 2.3 percent over the next 30 years.

As a consequence of the gap between expected and real earnings, in January an internal committee has been nominated to propose a sustainable suggestion to counter the effects of the decrease in bonds’ return rates.

The outcome, however, was not unanimous. On the 14th of October, eight out of nine members of the commission agreed on recommending an increase in stocks investments from 60 to 70 percent, at the expense of bond holdings, which provide a lower rate return.

This proposal was challenged by the chairman of the commission, Knut Anton Mork, former chief economist at Svenska Handelsbanken in Oslo, who advocated a cut to 50 percent in investments on equities, in order to transfer the difference on bonds.

His argument is that, although the scarcity in the oil and gas remaining in the ground over the last decade is an argument that supports a higher equity share, an increase in equity allocation would favour volatility, making contributions from the Oil Fund to the national treasury unpredictable.

The majority of the commission recognized the risk but regarded it as acceptable “provided that there is political will and ability to adapt economic policy to the accompanying increase in risk, in both the short and long run.” (Bloomberg, October 18th 2016 )

Essentially, the commission is concerned that more volatility may cause returns on the fund to suffer fluctuations and, therefore, to not always meet the budgetary needs of Norway.

The Norwegian government is allowed to withdraw up to 4 percent of the fund’s value each year to use in the budget, although presently, given the low returns, it is only using about 3 percent. The commission suggested “one potential margin of safety” would be to reduce the possibility of the government to access revenues from the fund to the level of the predicted rate return.

The final report has been submitted to Norway’s Ministry of Finance, Siv Jensen, who is in charge for presenting to the Norwegian Parliament the centre-right government’s position in spring 2017. If the final decision were to go through the allocation change, as senior insiders seem to predict, international economy would experience major consequences, as the fund would come to own 0.9 percent of the world’s equity, a sharp increase from the current 0.8 percent.

Carlo Urbano