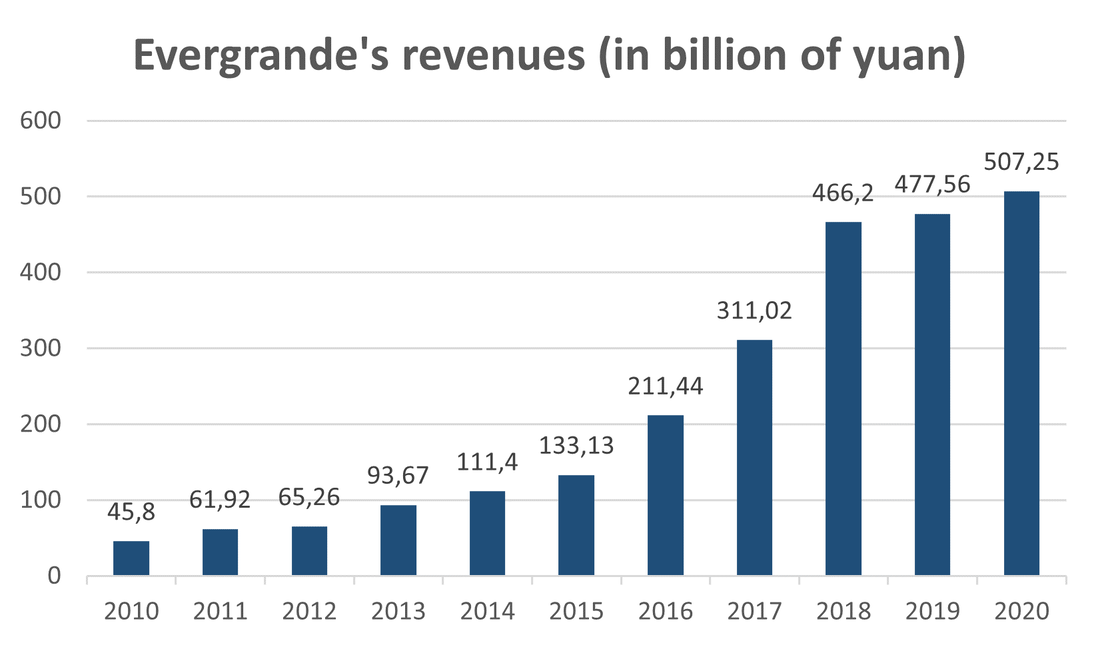

Evergrande Group is the second largest property developer in China by sales, founded in 1996 by Xu Jiayin. The company sells apartments to mostly upper and middle-income dwellers and in 2018 it became the most valuable real estate company in the world, with more than 400 billion Yuan ($62 billion) in revenues. Evergrande was listed on the Stock Exchange of Hong Kong in 2009. It currently owns more than 1300 projects in more than 280 cities across China.

Over the past 15 years the company has embarked on an impressive growth journey based on its “high debt, high leverage, high turnover and low cost” business model. This growth, however, has occurred amidst China’s broader organization and housing boom, which urbanized much of the country and caused nearly three quarters of household wealth to be tied up in housing. Thus, it came as no surprise that Evergrande was put at the centre of an economy that was dependent on its property market for economic growth.

Over the past 15 years the company has embarked on an impressive growth journey based on its “high debt, high leverage, high turnover and low cost” business model. This growth, however, has occurred amidst China’s broader organization and housing boom, which urbanized much of the country and caused nearly three quarters of household wealth to be tied up in housing. Thus, it came as no surprise that Evergrande was put at the centre of an economy that was dependent on its property market for economic growth.

At its peak, Evergrande Group’s business model was not just limited to real estate development in the mass market but incorporated a much wider array of businesses including selling bottled water, owning China’s best professional football team and even started producing electric cars.

However, all of these positive developments came to a halt in recent years, when Evergrande’s extreme usage of leverage, that underpinned its incredible expansion, eventually caught up to it. deleveraging a top economic priority for both financial and non-financial companies. It cracked down on real estate financing via shadow banking channels such as trust loans and wealth management products, required banks to institute stronger oversight over real estate lending and compelled local governments to adopt more strict qualification criteria for developers to enter land auctions. The second reason for Evegrande’s debt problems is the fact that the Chinese property market has slowed down, resulting in less demand for new apartments. This is contributing to an overall slowdown of the Chinese economy which worsened Evergrande’s troubles.

At the time of the crackdown, Evergrande was the most leveraged real estate developer in China and the most exposed to shadow banking as a source of financing. In early 2017 Evergrande began making changes to its business model, focusing on improving cash flow and profitability rather than just scale. Amongst other strategies, Evergrande focused on a more asset light business model, offloaded a $8.9 billion of short-term debt, reduced its land acquisition cost, increased the share of real estate in smaller, less tightly regulated cities, and diversified into new business lines (including electric vehicles, tourism, and finance). Since then (March 2020), Evergrande has targeted to cut its debt by $23.3 billion annually for 3 years.

In August 2020 however, regulators met with 12 major property developers (including Evergrande) and introduced the “three red lines” scheme, which capped 3 different debt ratios of property developers.

Evergrande was above all three limits in September. In response, the developer unsuccessfully tried to sell some of its businesses and properties at discounted prices. However, as early as August 2020 Evergrande reportedly sent a letter to the provincial government of Guangdong warning officials that its payment due in January 2021 could cause a liquidity crisis and lead to systemic risk. Thus, by September 2021 Evergrande’s debt burden amounted to $305 billion, becoming the most indebted real estate company in the world. On Sept 14th, Evergrande officially told its investors it would not be able to fulfil all its debt obligations, as it struggled to generate demand for its contract sales, leading to low cash flows.

However, all of these positive developments came to a halt in recent years, when Evergrande’s extreme usage of leverage, that underpinned its incredible expansion, eventually caught up to it. deleveraging a top economic priority for both financial and non-financial companies. It cracked down on real estate financing via shadow banking channels such as trust loans and wealth management products, required banks to institute stronger oversight over real estate lending and compelled local governments to adopt more strict qualification criteria for developers to enter land auctions. The second reason for Evegrande’s debt problems is the fact that the Chinese property market has slowed down, resulting in less demand for new apartments. This is contributing to an overall slowdown of the Chinese economy which worsened Evergrande’s troubles.

At the time of the crackdown, Evergrande was the most leveraged real estate developer in China and the most exposed to shadow banking as a source of financing. In early 2017 Evergrande began making changes to its business model, focusing on improving cash flow and profitability rather than just scale. Amongst other strategies, Evergrande focused on a more asset light business model, offloaded a $8.9 billion of short-term debt, reduced its land acquisition cost, increased the share of real estate in smaller, less tightly regulated cities, and diversified into new business lines (including electric vehicles, tourism, and finance). Since then (March 2020), Evergrande has targeted to cut its debt by $23.3 billion annually for 3 years.

In August 2020 however, regulators met with 12 major property developers (including Evergrande) and introduced the “three red lines” scheme, which capped 3 different debt ratios of property developers.

- Liability-to-asset ratio (excl. advanced receipts) < 70%

- Net gearing ratio < 100%

- Cash-to-short-term debt ratio > 1x

Evergrande was above all three limits in September. In response, the developer unsuccessfully tried to sell some of its businesses and properties at discounted prices. However, as early as August 2020 Evergrande reportedly sent a letter to the provincial government of Guangdong warning officials that its payment due in January 2021 could cause a liquidity crisis and lead to systemic risk. Thus, by September 2021 Evergrande’s debt burden amounted to $305 billion, becoming the most indebted real estate company in the world. On Sept 14th, Evergrande officially told its investors it would not be able to fulfil all its debt obligations, as it struggled to generate demand for its contract sales, leading to low cash flows.

What could happen now

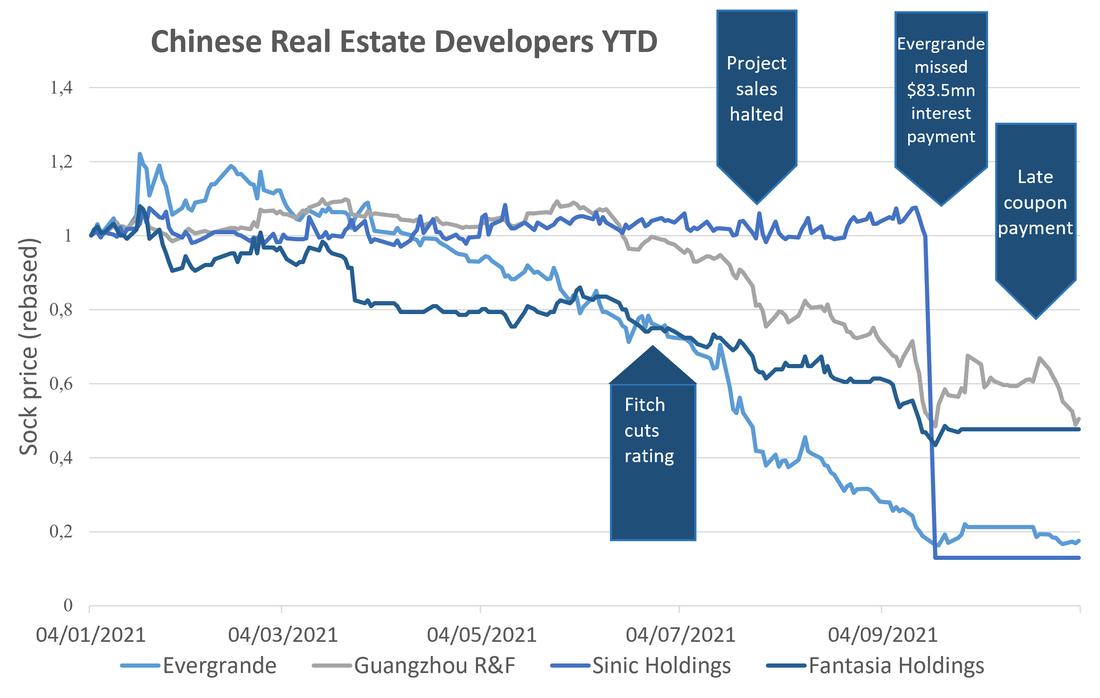

The fact that Evergrande missed interest payments has not formally triggered default on September 23. Although an eventual default was already very likely at the time, given the low chances of a sudden turnaround of the company’s fortunes and a number of other interest payments due over the following weeks, it could only be formally declared after a 30-day grace period. This bleak outlook was promptly reflected in the trading levels of Evergrande’s and comparable companies’ prices, as shown by the graph below. Some of Evergrande’s peers, such as Sinic and Fantasia, later also failed to meet their interest payment obligations. Although the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, characterized the risk of a contagion of the financial system from these actual and potential defaults as controllable, the news also affected economic growth outlooks and sovereign CDS spreads. On October 21, Evergrande avoided imminent default by making the coupon payment it had missed almost a month earlier. While the news was well received by stock and bond markets, the late payment arguably only delays rather than eliminates the need for Evergrande to engage with its creditors.

The fact that Evergrande missed interest payments has not formally triggered default on September 23. Although an eventual default was already very likely at the time, given the low chances of a sudden turnaround of the company’s fortunes and a number of other interest payments due over the following weeks, it could only be formally declared after a 30-day grace period. This bleak outlook was promptly reflected in the trading levels of Evergrande’s and comparable companies’ prices, as shown by the graph below. Some of Evergrande’s peers, such as Sinic and Fantasia, later also failed to meet their interest payment obligations. Although the People’s Bank of China, the country’s central bank, characterized the risk of a contagion of the financial system from these actual and potential defaults as controllable, the news also affected economic growth outlooks and sovereign CDS spreads. On October 21, Evergrande avoided imminent default by making the coupon payment it had missed almost a month earlier. While the news was well received by stock and bond markets, the late payment arguably only delays rather than eliminates the need for Evergrande to engage with its creditors.

In the meantime, it remained unclear how Chinese authorities would respond if the default would actually materialize. While Evergrande, and more broadly the Chinese real estate development sector, might be considered as too big to fail, PBoC officials took a tough stance, blaming the company’s failure on poor management and incautious growth policies while emphasizing the strength of the broader market. In this way they signalled that official support for the firm was not to be expected. The move has been widely interpreted as an attempt to maintain market discipline. However, given retail customers were an important source of liquidity for the company through wealth-management products and pre-sales of unfinished apartments into which many of those customers invested their life savings, ceasing the development of these projects might have a devastating effect on them and cause social unrest. Therefore, in the short term, Beijing prioritizes block sales of such projects to be completed by other developers to maintain social stability.

Beyond this immediate response, a default of Evergrande is likely to lead to a complicated and lengthy restructuring process, one of the largest in Chinese history. Valuable lessons about this scenario can be drawn from similar cases from the past. For example, in 2018, the default of Chinese conglomerate HNA could not be prevented despite large-scale asset sales. What followed was a years-long and still unfinished restructuring process of the firm, which operated in a number of sectors from airlines to financial services, including further asset sales. Earlier this year, state bankruptcy regulators took over the process and split the company into four entities to be wound down separately. Overall, proceedings are often not as straightforward as in developed markets since China lacks efficient mechanisms like the United States’ Chapter 11. The restructuring plan for HNA put forward by the regulator has prompted strong dissatisfaction among smaller creditors, alleging that it neglects their interests in an effort to close this embarrassing chapter in the story of a conglomerate with extremely deep connections in the highest spheres of Chinese politics. The case has come under broader scrutiny by investors regarding it as a precedent of what is to come for Evergrande.

Beyond this immediate response, a default of Evergrande is likely to lead to a complicated and lengthy restructuring process, one of the largest in Chinese history. Valuable lessons about this scenario can be drawn from similar cases from the past. For example, in 2018, the default of Chinese conglomerate HNA could not be prevented despite large-scale asset sales. What followed was a years-long and still unfinished restructuring process of the firm, which operated in a number of sectors from airlines to financial services, including further asset sales. Earlier this year, state bankruptcy regulators took over the process and split the company into four entities to be wound down separately. Overall, proceedings are often not as straightforward as in developed markets since China lacks efficient mechanisms like the United States’ Chapter 11. The restructuring plan for HNA put forward by the regulator has prompted strong dissatisfaction among smaller creditors, alleging that it neglects their interests in an effort to close this embarrassing chapter in the story of a conglomerate with extremely deep connections in the highest spheres of Chinese politics. The case has come under broader scrutiny by investors regarding it as a precedent of what is to come for Evergrande.

What effects could this crisis have on the global economy?

To date, the group has lost approximately over 80% on the Hong Kong stock exchange during 2021 and at the same time main Chinese RE competitors have suffered. The Hang Seng Property index, which includes many companies in the housing industry, has dropped to an historical minimum, and the value of the Yuan has been affected as well. The main market indexes in the West, instead, have been largely remained unaffected by the events in the Chinese real estate market.

Aside from investors, home buyers and suppliers, the credit market has been heavily struck, in particular the banking and insurance sector: if housing prices fall, banks have less assets as a guarantee of their loans and will have to raise provisions. A document released by the Chinese government shows that Evergrande’s liabilities are linked to 128 banks and 121 non-bank-institutions, to whom the PBoC has required to revise their exposure to loans and to asses financial risk on a monthly basis.

Chinese GDP growth during the third semester of 2021 has registered an increase of 4,9%, which confirms a slowdown (projections estimated 5,2% growth rate) caused by the crisis. This comes as no surplice, since the real-estate industry represents about 25% of the Chinese economy.

In late September, the fear of Evergrande’s collapse shocked all stock exchanges, and global finance in general, which has always invested and believed in Chinese bonds, especially in the West where hedge funds and common funds are exposed to the Chinese RE sector and to the eastern bond market in general. The risk of a world domino effect caused by Evergrande’s crash is alarming since China alone represents around 18% of global GDP and a more serious crisis would lead to a slowdown in other countries too.

After the measure of three red lines, the Government has not directly acted to save Evergrande from the default to admonish moral hazards of RE speculator developers, however it has directly contributed to make the bankruptcy of the Group, which is considered ‘too big to fail’, softer through a negotiated restructuring of debt (a so called “tidy default”): for example, it has asked the Guangdong district to help Evergrande in the assets’ sale and in negotiations with creditors, and it encouraged private and state-owned companies to buy some of the Group’s assets, bringing under control the default risk of contagion all over China and World.

Moreover, the PBoC has intervened many times, by inputting liquidity on markets for hundreds of billions of Yuan, in order to relieve investors’ anxieties and avoid the disastrous consequences on the Dragon’s economy that Evergrande’s crash would create.

To date, the group has lost approximately over 80% on the Hong Kong stock exchange during 2021 and at the same time main Chinese RE competitors have suffered. The Hang Seng Property index, which includes many companies in the housing industry, has dropped to an historical minimum, and the value of the Yuan has been affected as well. The main market indexes in the West, instead, have been largely remained unaffected by the events in the Chinese real estate market.

Aside from investors, home buyers and suppliers, the credit market has been heavily struck, in particular the banking and insurance sector: if housing prices fall, banks have less assets as a guarantee of their loans and will have to raise provisions. A document released by the Chinese government shows that Evergrande’s liabilities are linked to 128 banks and 121 non-bank-institutions, to whom the PBoC has required to revise their exposure to loans and to asses financial risk on a monthly basis.

Chinese GDP growth during the third semester of 2021 has registered an increase of 4,9%, which confirms a slowdown (projections estimated 5,2% growth rate) caused by the crisis. This comes as no surplice, since the real-estate industry represents about 25% of the Chinese economy.

In late September, the fear of Evergrande’s collapse shocked all stock exchanges, and global finance in general, which has always invested and believed in Chinese bonds, especially in the West where hedge funds and common funds are exposed to the Chinese RE sector and to the eastern bond market in general. The risk of a world domino effect caused by Evergrande’s crash is alarming since China alone represents around 18% of global GDP and a more serious crisis would lead to a slowdown in other countries too.

After the measure of three red lines, the Government has not directly acted to save Evergrande from the default to admonish moral hazards of RE speculator developers, however it has directly contributed to make the bankruptcy of the Group, which is considered ‘too big to fail’, softer through a negotiated restructuring of debt (a so called “tidy default”): for example, it has asked the Guangdong district to help Evergrande in the assets’ sale and in negotiations with creditors, and it encouraged private and state-owned companies to buy some of the Group’s assets, bringing under control the default risk of contagion all over China and World.

Moreover, the PBoC has intervened many times, by inputting liquidity on markets for hundreds of billions of Yuan, in order to relieve investors’ anxieties and avoid the disastrous consequences on the Dragon’s economy that Evergrande’s crash would create.

This time is different

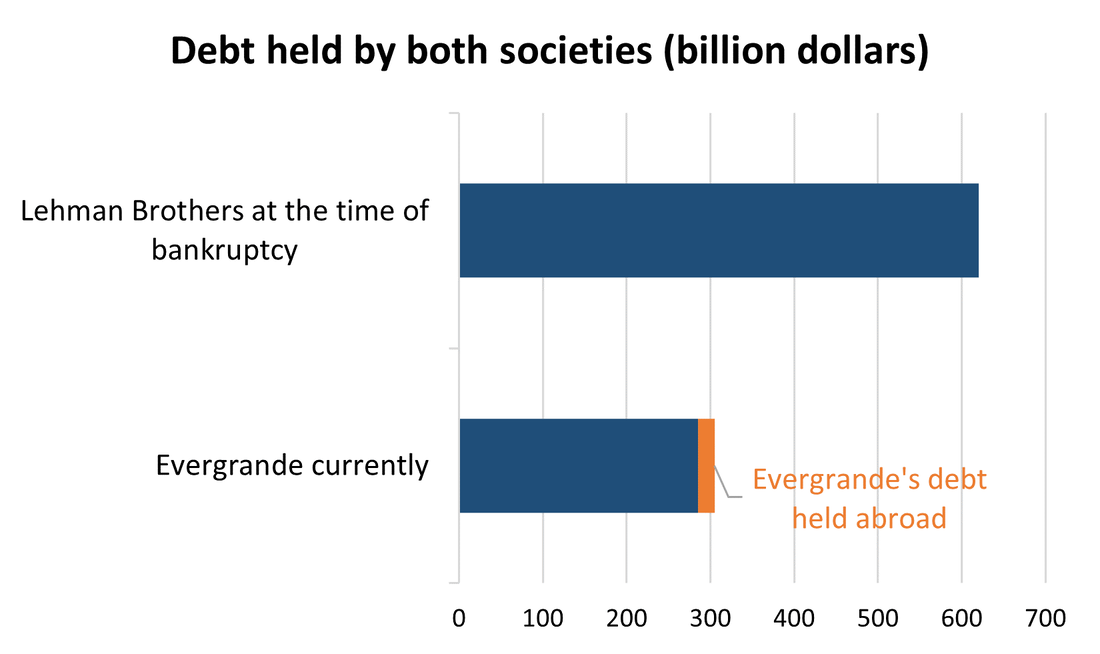

“The Chinese Lehman Brothers”: in this way has the Evergrande’s downturn been defined by some journalists and financial analysts due to its analogies with the events of the Great Financial Crisis and for the great fear and uncertainty which seems to have brought investors back in those bleak days of 2008; however, although the comparison is suggestive, in the last weeks this narrative has lost support. First, Evergrande is not so interconnected with the rest of the financial system as Lehman Brothers was. The latter owned several assets related to low-quality loans (so called sub-prime), and when the real estate bubble burst it found itself with billions evaporating from its balance sheet, causing a contagion effect to other banks and financial institutions. Evergrande, instead, is a group which operates in different sectors apart from real estate (it owns a football team and it is now present in the car industry, for example) and is faulty of adopting a business model too heavily reliant on leverage, which is still lower than the total exposure Lehman had in 2008. Moreover, the contagion effect could be avoided in the case of Evergrande thanks to the role of the Chinese government and the nature of Evergrande’s debts. The Chinese government is in fact expected to use its wide control over the country’s financial system to get banks and private investors to act when and as needed in order to soften Evergrande’s default.

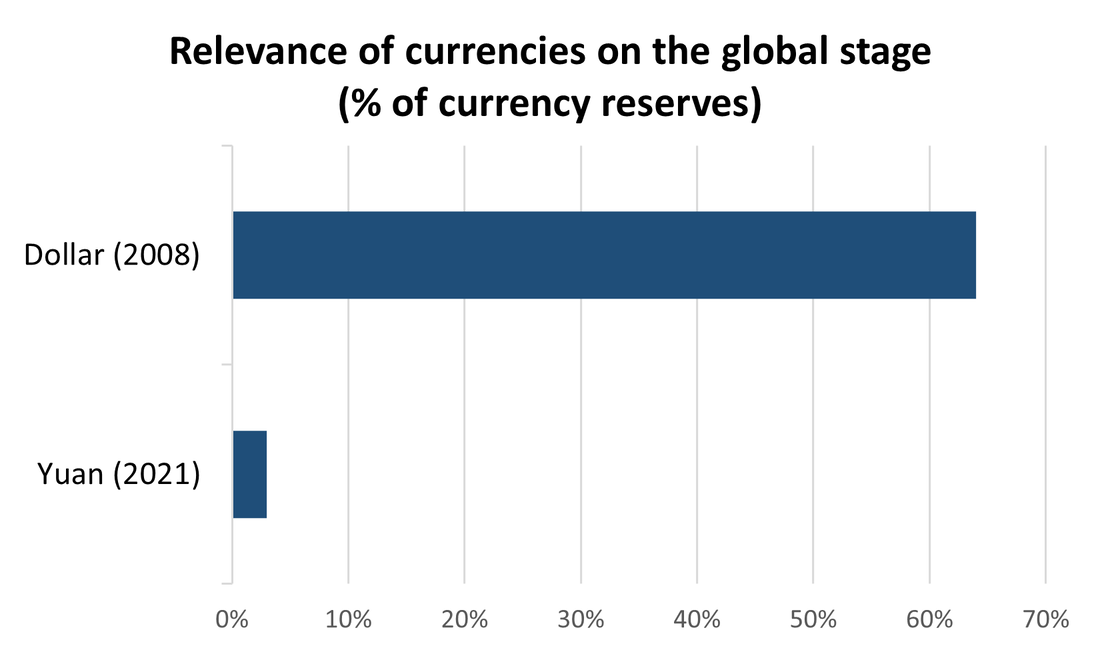

According to a JP Morgan’s analysis, the quantity of loans by the banking sector to Evergrande represent 0,2% of the total Chinese loans’ stock. Therefore, always in the American bank analysts’ opinion, repercussions of the eventual collapse would be severe but confined in the Chinese property market. Moreover, to bolster this thesis only 20 out of the 305 billion dollars of debt are owned abroad by investors and companies. At the same time, the two crises can hardly be compared as the relative importance of US economy and its currency in 2008 in far bigger than China’s and Yuan’s current one. To conclude, while the American government let Lehman Brothers fail without intervening, in China the government will not allow an uncontrolled housing crisis to cause millions of unemployed, impoverishing families which nowadays can glimpse the hope of an increase in income and quality of life.

“The Chinese Lehman Brothers”: in this way has the Evergrande’s downturn been defined by some journalists and financial analysts due to its analogies with the events of the Great Financial Crisis and for the great fear and uncertainty which seems to have brought investors back in those bleak days of 2008; however, although the comparison is suggestive, in the last weeks this narrative has lost support. First, Evergrande is not so interconnected with the rest of the financial system as Lehman Brothers was. The latter owned several assets related to low-quality loans (so called sub-prime), and when the real estate bubble burst it found itself with billions evaporating from its balance sheet, causing a contagion effect to other banks and financial institutions. Evergrande, instead, is a group which operates in different sectors apart from real estate (it owns a football team and it is now present in the car industry, for example) and is faulty of adopting a business model too heavily reliant on leverage, which is still lower than the total exposure Lehman had in 2008. Moreover, the contagion effect could be avoided in the case of Evergrande thanks to the role of the Chinese government and the nature of Evergrande’s debts. The Chinese government is in fact expected to use its wide control over the country’s financial system to get banks and private investors to act when and as needed in order to soften Evergrande’s default.

According to a JP Morgan’s analysis, the quantity of loans by the banking sector to Evergrande represent 0,2% of the total Chinese loans’ stock. Therefore, always in the American bank analysts’ opinion, repercussions of the eventual collapse would be severe but confined in the Chinese property market. Moreover, to bolster this thesis only 20 out of the 305 billion dollars of debt are owned abroad by investors and companies. At the same time, the two crises can hardly be compared as the relative importance of US economy and its currency in 2008 in far bigger than China’s and Yuan’s current one. To conclude, while the American government let Lehman Brothers fail without intervening, in China the government will not allow an uncontrolled housing crisis to cause millions of unemployed, impoverishing families which nowadays can glimpse the hope of an increase in income and quality of life.