Rodrigo Duterte, elected President of the Philippines on May 10th, had been able to secure the majority of MPs in the Congress and to establish a strong cult of his personality among all the people disappointed with institutions, which surprisingly represented 39% of the population. Posters and t-shirts representing an angry Duterte face can be found in houses all over the country, even in the most remote islands. The President signature policy is a bloody war on drugs, like the one he fought against petty crime when he was the Mayor of Davao, Philippines’ third-largest city. Through an informal network of killers and the quiet backing of the police, 7,000 people died in the second half of 2016, among which there were both drug dealers and occasional consumers too.

“If I make it to the presidential palace, I will do just what I did as mayor. You drug pushers, hold-up men and do-nothings, you better go out. Because I’d kill you. I’ll dump all of you into Manila Bay, and fatten all the fish there.”

Rodrigo Duterte, during the 2016 Electoral Campaign

After the 71-year-old President likened himself to Adolf Hitler, said he was willing to slaughter three million people, joked about not getting the chance to rape an Australian missionary gang-raped in Davao in 1989 and called former US President Barack Obama “son of a whore”, Amnesty International stated that the 7,000 killing might be considered as crimes against humanity. So far, the main foreign policy attainment of the new administration was the complete severing of diplomatic links with the US, at first offset by the reconciliation with China over the Spratly Islands territorial dispute. However, Duterte rapidly flip-flopped and changed his mind by emphasizing a new patriotic rhetoric against basically all the nearby countries, including China.

Despite a high domestic popularity, investors are worrying about the political and economic future of the nation. The public expects what could be ironically defined the dumbness of the commander in chief, to have an impact on the performance of the country. Nonetheless, GDP surged by 6.8% in 2016, making the Philippines among the world’s fastest growing countries, even topping China. Although it is still early to use the GDP, which is slower to adapt to political changes than other indicators, to track the new administration effect on the economy, data seem encouraging.

President Duterte vowed to open up the economy to new corporations to halt graft and protectionism, telling the country's oligarchs he owed them no favors. The populist leader said it was time to change regulations and liberalize sectors like energy, power and telecoms to make the country more competitive, and give Filipinos better services. However, there have been anti-business policies that generated clamor in the country. The new government stated it wanted to shut more than half of the country nickel mines, which makes the Philippines the world’s largest producer of nickel ore. The decision came after mine owners violated environmental and welfare laws, the government said. However, the move would breach contracts between private companies and the public administration and is causing widespread clamor in Manila’s business district.

Exports from the Philippines grew at the fastest rate in three years in January as shipments of electronics took off, jumping 22.5% year on year, coming in above a Bloomberg forecast of 10.5% growth. Consumer prices rose at the fastest rate since 2014, with CPI up 3.3% year-on-year in February. What seems good economic data are partially a consequence of the devaluation of the Philippines peso against the US Dollar, making export cheaper and imports more expensive. As already said, GDP is slow to adapt, but financial markets are not. There has been a consistent “Duterte effect” in the currency market, highlighted in the chart below.

Despite a high domestic popularity, investors are worrying about the political and economic future of the nation. The public expects what could be ironically defined the dumbness of the commander in chief, to have an impact on the performance of the country. Nonetheless, GDP surged by 6.8% in 2016, making the Philippines among the world’s fastest growing countries, even topping China. Although it is still early to use the GDP, which is slower to adapt to political changes than other indicators, to track the new administration effect on the economy, data seem encouraging.

President Duterte vowed to open up the economy to new corporations to halt graft and protectionism, telling the country's oligarchs he owed them no favors. The populist leader said it was time to change regulations and liberalize sectors like energy, power and telecoms to make the country more competitive, and give Filipinos better services. However, there have been anti-business policies that generated clamor in the country. The new government stated it wanted to shut more than half of the country nickel mines, which makes the Philippines the world’s largest producer of nickel ore. The decision came after mine owners violated environmental and welfare laws, the government said. However, the move would breach contracts between private companies and the public administration and is causing widespread clamor in Manila’s business district.

Exports from the Philippines grew at the fastest rate in three years in January as shipments of electronics took off, jumping 22.5% year on year, coming in above a Bloomberg forecast of 10.5% growth. Consumer prices rose at the fastest rate since 2014, with CPI up 3.3% year-on-year in February. What seems good economic data are partially a consequence of the devaluation of the Philippines peso against the US Dollar, making export cheaper and imports more expensive. As already said, GDP is slow to adapt, but financial markets are not. There has been a consistent “Duterte effect” in the currency market, highlighted in the chart below.

Comparison among Vietnam (VND), Thailand (THB) and Indonesia (IDR) currencies exchange rates to the US Dollar, with respect to the Philippines peso. Source: Bloomberg

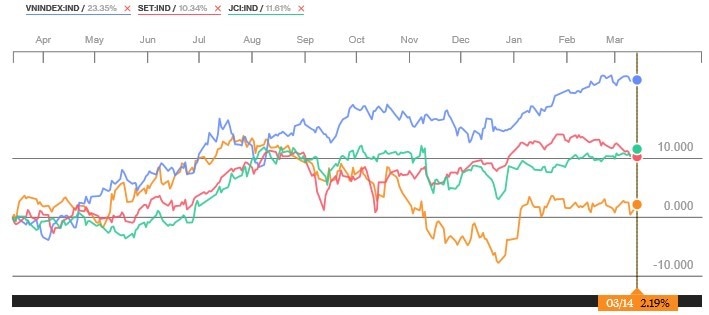

Among the major South-East Asia currencies, the Philippines peso is the only one that lost ground to the dollar in a very stable year, roughly 8%, hitting a 10-year low. Some articles wrongfully explained the fact with the uncertainty surrounding the FED decisions to hike the US interest rate, but this would have affected all the South-East Asian countries. The effect on financial markets becomes evident as we look at the Philippines stock exchange performance compared to peers in the same region of the world. Although Duterte’s archipelago recorded the highest GDP growth, PSEi, the main index in Manila, is basically at the same level as a year ago. In the meantime, Vietnam main index grew 23% and both Thailand and Indonesia gained a 10% increase.

Comparison among Vietnam (VNINDEX), Thailand (SET) and Indonesia (JCI) stock exchanges with respect to the PSEi, Philippines main index. Source: Bloomberg

IPO activity in the Philippines marked a downturn, too. At the end of June 2016, right after Duterte election, Cemex Philippines, the local division of Americas’ largest cement maker, raised US $465 million dollar in the country’s biggest initial public offering in more than two years. However, the price per share has been lowered to 10.75 pesos from a maximum of 17 pesos indicated in the February offering memorandum, meaning that the market changed, becoming more risk-averse due to the political uncertainty surrounding the new elected leader. The negative trend kept going in the following months, with the 2016 launching only 4 IPOs, less than half than a year before.

Mary Roxas-Divinagracia, managing partner at PwC Philippines, said in a report that 36 M&A deals worth US

$4.526 billion had been closed as of December 2016, considerably less than 2015’s 49 deals valued at US $14.98 billion. This year’s mergers and acquisitions activity was dampened by political uncertainties following the national election in May, she said. Although 2017 outlook is still promising, uncertainty increased greatly after last year’s Presidential Elections.

At this point, it is unfair to say that President Duterte extravagant decisions are going to slowdown Philippines economy, but the effect on the country’s financial markets cannot be denied. Signals of investors being afraid of the government moves are in the data, but the fear has not reached Main Street yet. Geopolitical tensions are rising all over the world and the South China Sea is one of the main stages for diplomatic relations, further fueling uncertainty. What the Philippines will face in 2017 and beyond depends largely in their leader, but it would be a bad mistake to exit such a promising emerging market story from the right track.

Corrado Valsecchi

Mary Roxas-Divinagracia, managing partner at PwC Philippines, said in a report that 36 M&A deals worth US

$4.526 billion had been closed as of December 2016, considerably less than 2015’s 49 deals valued at US $14.98 billion. This year’s mergers and acquisitions activity was dampened by political uncertainties following the national election in May, she said. Although 2017 outlook is still promising, uncertainty increased greatly after last year’s Presidential Elections.

At this point, it is unfair to say that President Duterte extravagant decisions are going to slowdown Philippines economy, but the effect on the country’s financial markets cannot be denied. Signals of investors being afraid of the government moves are in the data, but the fear has not reached Main Street yet. Geopolitical tensions are rising all over the world and the South China Sea is one of the main stages for diplomatic relations, further fueling uncertainty. What the Philippines will face in 2017 and beyond depends largely in their leader, but it would be a bad mistake to exit such a promising emerging market story from the right track.

Corrado Valsecchi