With the world economy slowing structurally, driven by the forces for “secular stagnation”, there is a constant debate about what policies to implement in order to tackle the lack of demand that is the very source of the problem. Monetary policies have been tried: negative interest rates have already moved from unthinkable to reality, along with QE programs all over the world. The next step is likely to include fiscal expansion, but the question is: will it be enough?

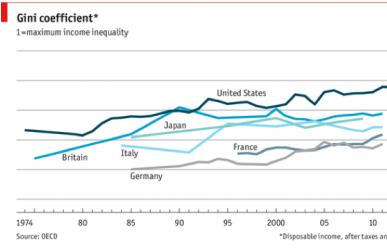

Rising inequality, as shown in the graph above, is one of the causes of the lack of demand we are facing.

Because richer people are more likely than poorer people to save money than to spend it, this phenomenon

dampens consumption and growth.

Because richer people are more likely than poorer people to save money than to spend it, this phenomenon

dampens consumption and growth.

“Conventional” monetary and fiscal policies have their pros and cons. Monetary policy is quick to implement, easy to coordinate and it is always backed by a broad consensus, but it does not impact spending directly and therefore its effects are hard to predict. Fiscal policy instead has the huge advantage of affecting spending directly, but there is no public opinion consensus about it, and furthermore it is not timely ( it does not affect the economy right away), difficult to implement and it is too much politicized. So, what if there would be a policy able to overcome the weaknesses of both approaches?

The answer that is coming up always more frequently in the financial world could seem revolutionary, but is in fact 47 years old: the so – called “helicopter drop”. The expression was coined in 1969 by Milton Friedman, to exemplify a basic principle: if a central bank wants to raise inflation and output in an economy that is running substantially below potential, one of the most effective tools would be simply to give everyone direct money transfers. While the very concept could seem unconceivable in a modern western type of economy, huge names are advocating for it, among others Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, and Ray Dalio, founder of the world’s largest hedge fund; so let’s try to give it a deeper look.

A literal helicopter drop would lead to riots, of course. But cash could be placed directly into bank accounts or the government could give investors a tax rebate, with the central bank creating the money to do so. Blyth and Lonergan (via Foreign Affairs) suggest that:

“The government could distribute cash equally to all households in terms of income, or even better, aim for the bottom 80 per cent of households in terms of income. Targeting those who earn the least would have two primary benefits. For one thing, lower-income households are more prone to consume, so they would provide a greater boost to spending. For another, the policy would offset rising income inequality.”

Furthermore, under existing monetary arrangements, it would also generate a permanent rise in the reserves of commercial banks at the central bank. The easy way to contain any long-term monetary effects would be to raise reserve requirements. These could then become a desirable feature of our unstable banking systems.

The question could be: would it be legal under the current EU legislation? According to Lonergan, it would be not only legal, but a legal obligation of the European Central Bank (ECB). The trick lies in the proper construction of helicopter drops. The euro-area version of it would be cash transfers from the ECB to households, which could take the form of perpetual zero coupon loans, intermediated by banks (TLTRO). This is not fiscal policy as defined by EU law. It involves the monetary base and would be implemented independently of national treasuries and budgetary policies, and would therefore count as monetary policy. This would protect the independence of the ECB and fall within the price stability mandate.

Obviously there are problems as well with this kind of policy, such as effects on bond prices with soaring inflation or the impact on exchange rates due to non simultaneous international implementation, but the main difficulties would probably be practical. Even resorting to old fashioned methods, such as using electoral registers, it would be almost impossible to distribute the money without excluding anyone (from immigrants to prisoners) and in an equal way, thus creating turmoil in the public opinion.

Maybe the “helicopter drop” will not be the answer to the challenge of current stagnation, but one thing is for sure: central bankers and politicians will have to be very creative in order to win this battle, because the monetary policy as we know it is certainly not working. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would put it, Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.

Mattia Borello

The answer that is coming up always more frequently in the financial world could seem revolutionary, but is in fact 47 years old: the so – called “helicopter drop”. The expression was coined in 1969 by Milton Friedman, to exemplify a basic principle: if a central bank wants to raise inflation and output in an economy that is running substantially below potential, one of the most effective tools would be simply to give everyone direct money transfers. While the very concept could seem unconceivable in a modern western type of economy, huge names are advocating for it, among others Ben Bernanke, former chairman of the Federal Reserve, and Ray Dalio, founder of the world’s largest hedge fund; so let’s try to give it a deeper look.

A literal helicopter drop would lead to riots, of course. But cash could be placed directly into bank accounts or the government could give investors a tax rebate, with the central bank creating the money to do so. Blyth and Lonergan (via Foreign Affairs) suggest that:

“The government could distribute cash equally to all households in terms of income, or even better, aim for the bottom 80 per cent of households in terms of income. Targeting those who earn the least would have two primary benefits. For one thing, lower-income households are more prone to consume, so they would provide a greater boost to spending. For another, the policy would offset rising income inequality.”

Furthermore, under existing monetary arrangements, it would also generate a permanent rise in the reserves of commercial banks at the central bank. The easy way to contain any long-term monetary effects would be to raise reserve requirements. These could then become a desirable feature of our unstable banking systems.

The question could be: would it be legal under the current EU legislation? According to Lonergan, it would be not only legal, but a legal obligation of the European Central Bank (ECB). The trick lies in the proper construction of helicopter drops. The euro-area version of it would be cash transfers from the ECB to households, which could take the form of perpetual zero coupon loans, intermediated by banks (TLTRO). This is not fiscal policy as defined by EU law. It involves the monetary base and would be implemented independently of national treasuries and budgetary policies, and would therefore count as monetary policy. This would protect the independence of the ECB and fall within the price stability mandate.

Obviously there are problems as well with this kind of policy, such as effects on bond prices with soaring inflation or the impact on exchange rates due to non simultaneous international implementation, but the main difficulties would probably be practical. Even resorting to old fashioned methods, such as using electoral registers, it would be almost impossible to distribute the money without excluding anyone (from immigrants to prisoners) and in an equal way, thus creating turmoil in the public opinion.

Maybe the “helicopter drop” will not be the answer to the challenge of current stagnation, but one thing is for sure: central bankers and politicians will have to be very creative in order to win this battle, because the monetary policy as we know it is certainly not working. As Sir Arthur Conan Doyle would put it, Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.

Mattia Borello