Introduction

How do you go from steadily climbing Bloomberg Billionaires Index to a humiliating bankruptcy? The fall of FTX, one of the world's largest cryptocurrency exchanges, has been in every newspaper since November 11th. But who is Sam Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old founder of FTX? And was it all only a "$8bn accident"?

The key players

After graduating in physics at MIT, Sam Bankman-Fried started working as a trader at Jane Street Capital, specializing in ETF arbitrage strategies. He immediately understood the immense opportunities offered by the cryptocurrency market: first, he focused on Bitcoin and then, in 2017, founded the quantitative trading firm Alameda Research, led by his young protégé Caroline Ellison. Since then, it was not long before SBF decided to set up FTX in 2019, while Alameda should just have incentivized the crypto exchange to perform at its best. Nevertheless, this relationship is among the most controversial issues of the whole scandal.

FTX, valued at $32bn, seemed to be the vanguard of a new crypto economy. SBF, with a private fortune of $24bn, has been compared to a modern J.P. Morgan for backing up the crypto industry after the Luna crash back in September. Although this is undoubtedly not the usual portrait of a company that is going to collapse, the downfall of FTX may not have been as sudden as it initially seemed. Former employees describe it as a “feudal” organization, where all the decision-making power was in the hands of SBF and a limited group of loyal friends in their 20s, living together in luxurious accommodations in the Bahamas. Moreover, the business was deeply understaffed: the same SBF proudly declared to have resisted many calls from venture capitalists asking him to increase the number of employees, which stood at about 300. Nonetheless, the leading causes of the bankruptcy are believed to be a lack of security measures and control, together with liquidity problems and managerial issues; all of which will be further discussed later in the article.

The collapse

FTX problems first appeared on November 2nd, when CoinDesk revealed the unusually close relationship between Alameda Research and the crypto exchange. The trading firm’s balance sheet was composed of illiquid assets and heavily depended on FTT, the token issued by its ‘sister company’ and usable in their ecosystem. Following the recent crypto market compression, the value of FTT declined, and Alameda was revealed to be insolvent. In response, Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao (CZ) revealed that the world’s most prominent digital currency exchange, which held $23m FTX tokens, would have liquidated any of them “due to recent revelations”. This news led to a massive $6bn withdrawal rush by FTX users in three days. After declaring on Twitter that “FTX is fine”, with posts later deleted, SBF finally contacted CZ asking for help. On November 7th, Binance agreed to rescue the crypto exchange with a non-binding letter of intent. However, after due diligence, CZ decided not to go further with the deal, citing that “the issues are beyond our control or ability to help”. Since then, cryptocurrency prices experienced a free fall, and on November 11th, FTX filed for bankruptcy protection in Delaware Federal Court, unable to meet $5bn in customers’ withdrawals. Currently, the crypto exchange is the target of investigations by the SEC and the Justice Department to determine possible violations of financial regulations. After his resignation, SBF was replaced by John Ray III, a restructuring expert who had already handled several bankruptcy cases, including Enron’s collapse in 2001.

How do you go from steadily climbing Bloomberg Billionaires Index to a humiliating bankruptcy? The fall of FTX, one of the world's largest cryptocurrency exchanges, has been in every newspaper since November 11th. But who is Sam Bankman-Fried, the 30-year-old founder of FTX? And was it all only a "$8bn accident"?

The key players

After graduating in physics at MIT, Sam Bankman-Fried started working as a trader at Jane Street Capital, specializing in ETF arbitrage strategies. He immediately understood the immense opportunities offered by the cryptocurrency market: first, he focused on Bitcoin and then, in 2017, founded the quantitative trading firm Alameda Research, led by his young protégé Caroline Ellison. Since then, it was not long before SBF decided to set up FTX in 2019, while Alameda should just have incentivized the crypto exchange to perform at its best. Nevertheless, this relationship is among the most controversial issues of the whole scandal.

FTX, valued at $32bn, seemed to be the vanguard of a new crypto economy. SBF, with a private fortune of $24bn, has been compared to a modern J.P. Morgan for backing up the crypto industry after the Luna crash back in September. Although this is undoubtedly not the usual portrait of a company that is going to collapse, the downfall of FTX may not have been as sudden as it initially seemed. Former employees describe it as a “feudal” organization, where all the decision-making power was in the hands of SBF and a limited group of loyal friends in their 20s, living together in luxurious accommodations in the Bahamas. Moreover, the business was deeply understaffed: the same SBF proudly declared to have resisted many calls from venture capitalists asking him to increase the number of employees, which stood at about 300. Nonetheless, the leading causes of the bankruptcy are believed to be a lack of security measures and control, together with liquidity problems and managerial issues; all of which will be further discussed later in the article.

The collapse

FTX problems first appeared on November 2nd, when CoinDesk revealed the unusually close relationship between Alameda Research and the crypto exchange. The trading firm’s balance sheet was composed of illiquid assets and heavily depended on FTT, the token issued by its ‘sister company’ and usable in their ecosystem. Following the recent crypto market compression, the value of FTT declined, and Alameda was revealed to be insolvent. In response, Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao (CZ) revealed that the world’s most prominent digital currency exchange, which held $23m FTX tokens, would have liquidated any of them “due to recent revelations”. This news led to a massive $6bn withdrawal rush by FTX users in three days. After declaring on Twitter that “FTX is fine”, with posts later deleted, SBF finally contacted CZ asking for help. On November 7th, Binance agreed to rescue the crypto exchange with a non-binding letter of intent. However, after due diligence, CZ decided not to go further with the deal, citing that “the issues are beyond our control or ability to help”. Since then, cryptocurrency prices experienced a free fall, and on November 11th, FTX filed for bankruptcy protection in Delaware Federal Court, unable to meet $5bn in customers’ withdrawals. Currently, the crypto exchange is the target of investigations by the SEC and the Justice Department to determine possible violations of financial regulations. After his resignation, SBF was replaced by John Ray III, a restructuring expert who had already handled several bankruptcy cases, including Enron’s collapse in 2001.

Binance backs out of FTX acquisition - Source: Twitter

The failure of Corporate Governance (if there was any)

“Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here. From compromised systems integrity and faulty regulatory oversight abroad to the concentration of control in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals, this situation is unprecedented.”

The opening statement of the Chapter 11 declaration submitted by the new FTX CEO John Ray III, represents a perfect first picture to portray the dramatic, almost comic, situation he has discovered since his first day as chief executive officer. The thirty-page document highlights a disastrous condition that no one would have expected until a month ago. Extremely superficial and inaccurate bookkeeping, an inexistent board, the absence of any form of audit, and unexplained corporate funds expenditures are just a few of the many issues Ray discovered and reported in the bankruptcy filing. Glossing over the untrustworthiness of the financial statements, which will be discussed later in the article, reading through the declaration is crucial to better understand how the series of management failures led to the bankruptcy of FTX.

Let us start with the builder of the house of cards, Sam Bankman-Fried, and its inner circle of “inexperienced and unsophisticated” friends and colleagues. To mention a few names, Caroline Ellison, CEO of Alameda and romantically involved with SBF; Gary Wang, Alameda and FTX’s co-founder and SBF’s childhood friend; Nishad Singh, the CEO’s best friend in university; William MacAskill, professor at Oxford and SBF’s mentor. They were incapable of providing the CEO with reliable and worthy advice and always unconditionally supportive in all his risky, to say the least, choices. At the time he stepped down as CEO of FTX, the company’s board of directors was inexistent, as only constituted by SBF, and there is no record of any official top management meetings, underlying the inconsistency of the company’s corporate governance. The upper management structure gave him unlimited power in the decision-making process and the freedom to conduct several irregularities. By choosing not to undergo any external audit procedure, all those practices remained unobserved for months; it was just when Binance conducted due diligence in the first stages of acquiring FTX that it all came to the surface.

“Never in my career have I seen such a complete failure of corporate controls and such a complete absence of trustworthy financial information as occurred here. From compromised systems integrity and faulty regulatory oversight abroad to the concentration of control in the hands of a very small group of inexperienced, unsophisticated and potentially compromised individuals, this situation is unprecedented.”

The opening statement of the Chapter 11 declaration submitted by the new FTX CEO John Ray III, represents a perfect first picture to portray the dramatic, almost comic, situation he has discovered since his first day as chief executive officer. The thirty-page document highlights a disastrous condition that no one would have expected until a month ago. Extremely superficial and inaccurate bookkeeping, an inexistent board, the absence of any form of audit, and unexplained corporate funds expenditures are just a few of the many issues Ray discovered and reported in the bankruptcy filing. Glossing over the untrustworthiness of the financial statements, which will be discussed later in the article, reading through the declaration is crucial to better understand how the series of management failures led to the bankruptcy of FTX.

Let us start with the builder of the house of cards, Sam Bankman-Fried, and its inner circle of “inexperienced and unsophisticated” friends and colleagues. To mention a few names, Caroline Ellison, CEO of Alameda and romantically involved with SBF; Gary Wang, Alameda and FTX’s co-founder and SBF’s childhood friend; Nishad Singh, the CEO’s best friend in university; William MacAskill, professor at Oxford and SBF’s mentor. They were incapable of providing the CEO with reliable and worthy advice and always unconditionally supportive in all his risky, to say the least, choices. At the time he stepped down as CEO of FTX, the company’s board of directors was inexistent, as only constituted by SBF, and there is no record of any official top management meetings, underlying the inconsistency of the company’s corporate governance. The upper management structure gave him unlimited power in the decision-making process and the freedom to conduct several irregularities. By choosing not to undergo any external audit procedure, all those practices remained unobserved for months; it was just when Binance conducted due diligence in the first stages of acquiring FTX that it all came to the surface.

Sam Bankman-Fried and the FTX team on April 30th – Source: Twitter

The first concerns on Sam Bankman-Fried’s managerial skills were raised in 2018, when FTX did not exist, and he was leading Alameda. Tara Mac Auley, Alameda’s co-founder, quit the company, followed by a group of employees, “in part because of concerns over risk management and business ethics”, as she has recently tweeted. They condemned the absence of a rigorous risk management system, the CEO’s closure concerning advice from his colleagues, and how he treated the employees, creating a tense working environment.

The first defect in the company’s operations is the absence of centralized cash management, with no official and rigorous record of either bank accounts or account signatories, not to mention the lack of control over the reliability of banking partners. For instance, supervisors requested all the disbursements through an online chat and approved them with emojis. SBF spent more than $300m of corporate funds to purchase luxury real estate for himself and his team in the Bahamas. He again used the company’s funds to grant himself and other company members loans for more than $1bn. Several billions of dollars of extra-cryptocurrency investments are yet to be located due to a lack of booking and recording of the investment activities.

A layer of mystery also covers the company’s everyday activities and employees. All the internal communications happened through self-deleting apps promoted by SBF and soon used by all employees. At the same time, there is no official record of all the workers employed by the company, raising doubts about the hiring process and modalities.

A well-built trap for investors

One question at this point might arise: how is it possible that no one could seek any of these flaws in the past months, and FTX kept raising funds from investors worldwide? The credit goes to the ability of SBF to convince everyone, including regulators, of the trustworthiness of his business model and his team, combined with a well-built and costly public relations campaign, which included donations to nonprofits, political contributions, investments in consulting and media outlets.

The first defect in the company’s operations is the absence of centralized cash management, with no official and rigorous record of either bank accounts or account signatories, not to mention the lack of control over the reliability of banking partners. For instance, supervisors requested all the disbursements through an online chat and approved them with emojis. SBF spent more than $300m of corporate funds to purchase luxury real estate for himself and his team in the Bahamas. He again used the company’s funds to grant himself and other company members loans for more than $1bn. Several billions of dollars of extra-cryptocurrency investments are yet to be located due to a lack of booking and recording of the investment activities.

A layer of mystery also covers the company’s everyday activities and employees. All the internal communications happened through self-deleting apps promoted by SBF and soon used by all employees. At the same time, there is no official record of all the workers employed by the company, raising doubts about the hiring process and modalities.

A well-built trap for investors

One question at this point might arise: how is it possible that no one could seek any of these flaws in the past months, and FTX kept raising funds from investors worldwide? The credit goes to the ability of SBF to convince everyone, including regulators, of the trustworthiness of his business model and his team, combined with a well-built and costly public relations campaign, which included donations to nonprofits, political contributions, investments in consulting and media outlets.

A digital tombstone of those who invested in FTX - Source: Financial Times

While it is understandable how SBF’s charisma and rhetoric induced many small investors to bet on FTX, fueled by celebrities’ endorsements, including Larry David, Tom Brady, and Stephen Curry, it is hard to conceive how some of the largest VCs firms in the industry invested large sums in one of the biggest collapses in recent history.

During three distinct fundraising rounds, FTX collected respectively $1bn, $420m, and $400m from well-known financial institutions, including Sequoia Capital, which committed almost $250m, Temasek, SoftBank, Thoma Bravo, BlackRock, and many others. As soon as the flaws of FTX came to the surface, one after the other, the VCs attempted to exit their investment, leading to the company’s collapse. Many funds have already given up, writing down to zero the value of their investment, while others are ready to take SBF to court with fraud allegations. At the same time, it is undoubtful that much of the blame for the losses lies with FTX management’s incapability to meet obligations and promises. Nevertheless, the evidence also highlights flaws in VCs’ due diligence that, at the very least, need careful examination.

The (un)real financial situation

Apart from FTX’s controversial corporate governance, two other major critical issues emerged from this series of events: the quality of FTX’s balance sheet and its relationship with Alameda Research, which was supposed to be an independent trading firm. In reality, the two firms had much closer relations than what was told to investors, creating vast conflicts of interest.

According to documents revealed by the Financial Times, FTX International held just $900m in easily sellable assets against $9bn of liabilities the day before it collapsed into bankruptcy. The most considerable portion of those liquid assets consisted in $470m of Robinhood shares owned by an SBF vehicle not listed in the bankruptcy filings, which included 134 corporate entities.

During three distinct fundraising rounds, FTX collected respectively $1bn, $420m, and $400m from well-known financial institutions, including Sequoia Capital, which committed almost $250m, Temasek, SoftBank, Thoma Bravo, BlackRock, and many others. As soon as the flaws of FTX came to the surface, one after the other, the VCs attempted to exit their investment, leading to the company’s collapse. Many funds have already given up, writing down to zero the value of their investment, while others are ready to take SBF to court with fraud allegations. At the same time, it is undoubtful that much of the blame for the losses lies with FTX management’s incapability to meet obligations and promises. Nevertheless, the evidence also highlights flaws in VCs’ due diligence that, at the very least, need careful examination.

The (un)real financial situation

Apart from FTX’s controversial corporate governance, two other major critical issues emerged from this series of events: the quality of FTX’s balance sheet and its relationship with Alameda Research, which was supposed to be an independent trading firm. In reality, the two firms had much closer relations than what was told to investors, creating vast conflicts of interest.

According to documents revealed by the Financial Times, FTX International held just $900m in easily sellable assets against $9bn of liabilities the day before it collapsed into bankruptcy. The most considerable portion of those liquid assets consisted in $470m of Robinhood shares owned by an SBF vehicle not listed in the bankruptcy filings, which included 134 corporate entities.

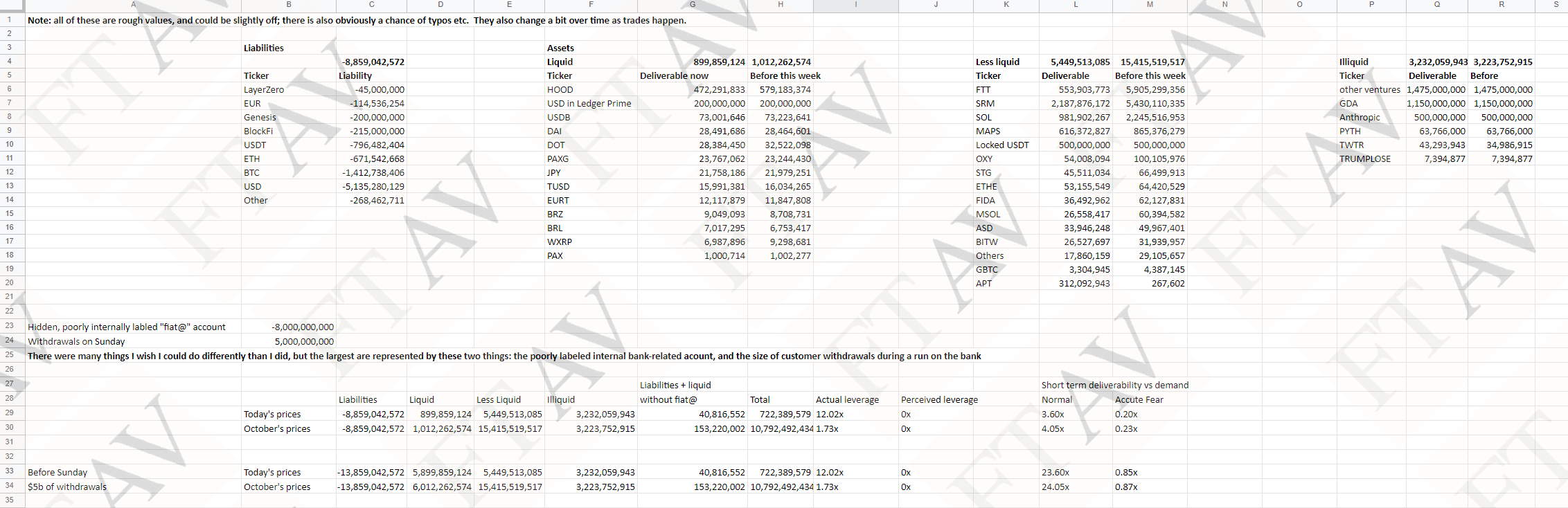

FTX’s balance sheet as of November 10th - Source: Financial Times

A spreadsheet listing FTX International’s assets and liabilities reported by the Financial Times (as represented above) showed that many investors would have been unable to liquidate their positions since liabilities were not covered by sufficient assets. It references $5bn of withdrawals on the Sunday before its draft, and a negative $8bn entry described as “hidden, poorly internally labeled ‘fiat@’ account”. Bankman-Fried told the Financial Times the $8bn related to funds “accidentally” extended to his trading firm, Alameda.

In the material for prospective investors, FTX Trading Ltd, the company behind the leading international exchange, is recorded as having liabilities of $8.9bn, the most significant portion of which is $5.1bn of US dollar balances. Usually, healthy companies have assets that cover all their liabilities. The spreadsheet says FTX Trading had a total of $9.6bn of assets, but it is unclear how much of that value could be realized. The vast majority of these assets were either illiquid investments, for example, in venture capitals, or crypto tokens that are not widely traded. For instance, the most considerable asset on the balance sheet was $2.2bn worth of a cryptocurrency called Serum. Serum’s total market value was just $88m after the bankruptcy filing, according to data providers that consider the coin’s liquidity. This evidence suggests that the real value of the assets would be far less if sold into the market.

Bankman-Fried was trying to sell the $472m of Robinhood shares, the largest liquid asset listed for FTX Trading, in privately negotiated deals. According to US securities filings, these shares were held in an Antigua and Barbuda entity called Emergent Fidelity, which SBF personally controls. Emergent Fidelity is not among the entities listed in the bankruptcy filing for FTX Trading. SBF was trying to sell the stocks at about a 20% discount to the market price, but he was unsuccessful since possible investors perceived high legal risks.

The second most liquid asset was $200m of cash held with Ledger Prime, a crypto investment firm owned by Alameda. No documents show other US dollar balances held by FTX Trading.

Ultimately, the spreadsheet says FTX Trading’s assets were $900m of “liquid” assets, $5.5bn of “less liquid” assets consisting of crypto tokens, and $3.2bn of illiquid private equity investments. There is also a voice for $7m in “TRUMPLOSE”, a token redeemable for $1 or $0 in case Trump loses or wins the 2024 Presidential election. There are no Bitcoins listed as assets, notwithstanding Bitcoin liabilities of $1.4bn.

Partners in crime - The links between Alameda and FTX

The trading arm of Sam Bankman-Fried’s cryptocurrency empire is Alameda Research. Even though Alameda and FTX should be two separate businesses, the division breaks down in a critical place: on Alameda’s balance sheet.

Alameda’s balance sheet is full of FTT, the token issued by FTX which grants holders a discount on trading fees on its marketplace. Alameda, therefore, relies on a foundation primarily made up of a coin that a sister company invented, not an independent asset like a fiat currency or another crypto. Alameda is also huge. As of June 30th, the company’s assets amounted to $14.6bn. Its single largest asset consists of $3.66bn of “unlocked FTT”, while the third-largest is a $2.16bn pile of “FTT collateral”. There is also $134m of cash and equivalents and a $2bn “investment in equity securities.”

Alameda Research has been allowed to exceed borrowing limits on FTX since its origins, which shows how close the two entities were. In 2019, when FTX was founded, Alameda accounted for 45% of the volume of transactions on the platform. In a Reuters report, SBF secretly transferred $10bn of customer funds from FTX to Alameda Research to prop up its liquidity. This transaction was done through a backdoor that did not trigger any red flags in the company’s systems. Of the $10bn transferred, a sum between $1bn and $2bn has reportedly disappeared.

What to expect next?

After the crash of FTX, Binance’s market power has broadened, further lowering competition in the crypto industry. Someone has argued about a possible intentional role played by CZ in the FTX collapse. However, he has publicly denied any deliberate involvement and any genuine personal interest in FTX bankruptcy, affirming that starting from now, regulators will focus their attention on big exchanges even more, making licenses harder to get.

CZ has addressed one of the main concerns of today’s investors: what’s next? How will the cryptocurrency market react to FTX’s decline? The first factors to consider are decreasing enthusiasm for crypto and, consequently, further fall in prices, as well as rising centralization of the crypto environment, resulting from the difficulties many players have faced during the last months and will increasingly face after FTX collapse. Along with these factors, the current debate on the future development of cryptocurrencies mainly focuses on the regulatory aspect. Investors’ and regulators’ pressure on crypto entities to disclose more information is likely to boost to safeguard clients, limit asset concentration and induce more conscious risk management. Lacking underlying rules of procedure and clear directives, these regulations may be from the traditional financial system to the cryptocurrency world, potentially generating convergence between the two. Finally, institutional investors might decide to change the way they interact with exchanges, given the extraordinary number of losses they suffered this November.

Indeed, as the Financial Times reports, investors are currently under scrutiny to “have invested their own and other people’s money in collapsed crypto exchange FTX”, ironically comparing the long list of well-known powerful institutions to a digital tombstone. Some of them refused to make any statement on the matter, and others, such as Sequoia Capital, declared to be shocked and denied any lack of proper due diligence at the time the investment was made. According to the experts, however, this case represents one of the most dramatic recent examples of what happens when a person who looks like a genius is given an excessively high amount of money without conducting any previous careful control.

Written by Chiara Evangelisti, Edoardo Miccio, and Federico Longhi

In the material for prospective investors, FTX Trading Ltd, the company behind the leading international exchange, is recorded as having liabilities of $8.9bn, the most significant portion of which is $5.1bn of US dollar balances. Usually, healthy companies have assets that cover all their liabilities. The spreadsheet says FTX Trading had a total of $9.6bn of assets, but it is unclear how much of that value could be realized. The vast majority of these assets were either illiquid investments, for example, in venture capitals, or crypto tokens that are not widely traded. For instance, the most considerable asset on the balance sheet was $2.2bn worth of a cryptocurrency called Serum. Serum’s total market value was just $88m after the bankruptcy filing, according to data providers that consider the coin’s liquidity. This evidence suggests that the real value of the assets would be far less if sold into the market.

Bankman-Fried was trying to sell the $472m of Robinhood shares, the largest liquid asset listed for FTX Trading, in privately negotiated deals. According to US securities filings, these shares were held in an Antigua and Barbuda entity called Emergent Fidelity, which SBF personally controls. Emergent Fidelity is not among the entities listed in the bankruptcy filing for FTX Trading. SBF was trying to sell the stocks at about a 20% discount to the market price, but he was unsuccessful since possible investors perceived high legal risks.

The second most liquid asset was $200m of cash held with Ledger Prime, a crypto investment firm owned by Alameda. No documents show other US dollar balances held by FTX Trading.

Ultimately, the spreadsheet says FTX Trading’s assets were $900m of “liquid” assets, $5.5bn of “less liquid” assets consisting of crypto tokens, and $3.2bn of illiquid private equity investments. There is also a voice for $7m in “TRUMPLOSE”, a token redeemable for $1 or $0 in case Trump loses or wins the 2024 Presidential election. There are no Bitcoins listed as assets, notwithstanding Bitcoin liabilities of $1.4bn.

Partners in crime - The links between Alameda and FTX

The trading arm of Sam Bankman-Fried’s cryptocurrency empire is Alameda Research. Even though Alameda and FTX should be two separate businesses, the division breaks down in a critical place: on Alameda’s balance sheet.

Alameda’s balance sheet is full of FTT, the token issued by FTX which grants holders a discount on trading fees on its marketplace. Alameda, therefore, relies on a foundation primarily made up of a coin that a sister company invented, not an independent asset like a fiat currency or another crypto. Alameda is also huge. As of June 30th, the company’s assets amounted to $14.6bn. Its single largest asset consists of $3.66bn of “unlocked FTT”, while the third-largest is a $2.16bn pile of “FTT collateral”. There is also $134m of cash and equivalents and a $2bn “investment in equity securities.”

Alameda Research has been allowed to exceed borrowing limits on FTX since its origins, which shows how close the two entities were. In 2019, when FTX was founded, Alameda accounted for 45% of the volume of transactions on the platform. In a Reuters report, SBF secretly transferred $10bn of customer funds from FTX to Alameda Research to prop up its liquidity. This transaction was done through a backdoor that did not trigger any red flags in the company’s systems. Of the $10bn transferred, a sum between $1bn and $2bn has reportedly disappeared.

What to expect next?

After the crash of FTX, Binance’s market power has broadened, further lowering competition in the crypto industry. Someone has argued about a possible intentional role played by CZ in the FTX collapse. However, he has publicly denied any deliberate involvement and any genuine personal interest in FTX bankruptcy, affirming that starting from now, regulators will focus their attention on big exchanges even more, making licenses harder to get.

CZ has addressed one of the main concerns of today’s investors: what’s next? How will the cryptocurrency market react to FTX’s decline? The first factors to consider are decreasing enthusiasm for crypto and, consequently, further fall in prices, as well as rising centralization of the crypto environment, resulting from the difficulties many players have faced during the last months and will increasingly face after FTX collapse. Along with these factors, the current debate on the future development of cryptocurrencies mainly focuses on the regulatory aspect. Investors’ and regulators’ pressure on crypto entities to disclose more information is likely to boost to safeguard clients, limit asset concentration and induce more conscious risk management. Lacking underlying rules of procedure and clear directives, these regulations may be from the traditional financial system to the cryptocurrency world, potentially generating convergence between the two. Finally, institutional investors might decide to change the way they interact with exchanges, given the extraordinary number of losses they suffered this November.

Indeed, as the Financial Times reports, investors are currently under scrutiny to “have invested their own and other people’s money in collapsed crypto exchange FTX”, ironically comparing the long list of well-known powerful institutions to a digital tombstone. Some of them refused to make any statement on the matter, and others, such as Sequoia Capital, declared to be shocked and denied any lack of proper due diligence at the time the investment was made. According to the experts, however, this case represents one of the most dramatic recent examples of what happens when a person who looks like a genius is given an excessively high amount of money without conducting any previous careful control.

Written by Chiara Evangelisti, Edoardo Miccio, and Federico Longhi

Sources:

- Dealroom

- CNBC

- Coindesk

- Cryptonews

- Cryptonomist

- Financial Times

- Forbes

- Reuters

- The Guardian

- The New York Times

- The Wall Street Journal

- Visual Capitalist

- Wired