On April 4th Jack Lew, the American treasury secretary, announced a renewed clampdown on inversions, takeovers that allow American firms to shift their tax domicile to countries with lower corporate tax rates, leaving the American treasury with empty hands. Two days later, Pfizer, an American pharmaceutical company, suspended the negotiations concerning its announced acquisition of Allergan. The deal, deemed to become the third-largest takeover in history, allowed Pfizer to shift its tax domicile to Dublin. The crackdown took the market by surprise and the reaction was sharp: Pfizer valuation sunk by $13 billion in 48 hours.

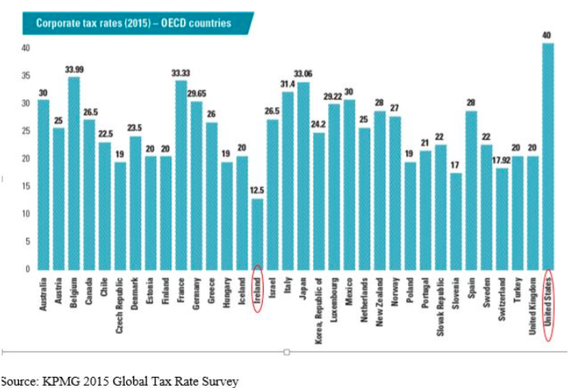

Pfizer reaction is the proof of the financial rather than strategic rationale behind the deal. What is the context of such a behaviour? Much of the American tax system dates back to the 80s, which makes it stand as severely outdated in a globalized world. First, American tax authority imposes taxes on global profits, unlike most European authorities, which aim to tax only the local profits of global firms. Second, America’s headline corporate-tax rate is 40% against an average of 25% of other rich countries.

Pfizer reaction is the proof of the financial rather than strategic rationale behind the deal. What is the context of such a behaviour? Much of the American tax system dates back to the 80s, which makes it stand as severely outdated in a globalized world. First, American tax authority imposes taxes on global profits, unlike most European authorities, which aim to tax only the local profits of global firms. Second, America’s headline corporate-tax rate is 40% against an average of 25% of other rich countries.

This disparity represents a treasure trove of arbitrage for American firms, which in fact pay far less than the official rate. In 2015, the 50 largest listed firms in America just paid taxes equivalent to the 24% of their pre-tax profits, far less than the 50 biggest European listed firms, which paid 35% of their global profits in tax. Apple paid 18% and Pfizer 27%.

How do they manage to do so? Firms allocate profits to countries with lower tax rates and allocate debt to their American subsidiaries, reducing their profits there and increasing them elsewhere, a technique named “earnings stripping”. These manoeuvres culminate in tax inversions: a firm buys a foreign firm and adopts its tax domicile. This is especially easy for firms based on intellectual property, which has no physical location, as pharma and tech firms are. The merged company, no longer American, can return the stored cash to shareholders paying it out as dividends or via buybacks without paying American taxes. Apple keeps $92 billion parked abroad. Pfizer $80 billion.

“After an inversion, many of these companies continue to take advantage of the benefits of being based in the United States--including our rule of law, skilled workforce, infrastructure, and research, and development capabilities--all while shifting a greater tax burden to other businesses and American families,” said Treasury Secretary Jack Lew.

As true as this may be, the Congress should adopt a wider and longer-term perspective on the issue, bringing the tax-rate closer to other advanced economies and charging American tax only on American profits. This would distend relationship with firms and stabilize the tax revenues as a percentage of GDP.

Chiara Cauli