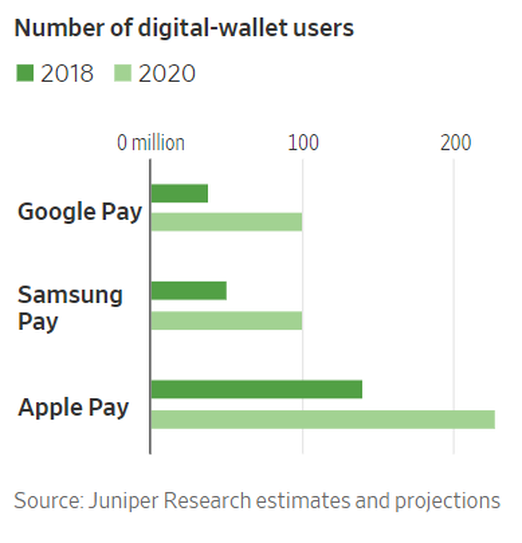

Google announced that it will offer personal checking accounts through its Google Pay app, starting from next year. The project, code-named Cache, will be launched in partnership with Citigroup and Stanford Federal Credit Union. Other banks could join up later, although the full plan is yet to be fully disclosed by the Mountain View-based company. The project does not represent Google’s first attempt to enter the personal finance industry, as its first payment-related product dates back to 2011, when it first unveiled Google Wallet as a way for users to send money to each other. However, Google's payment system did not perform as expected until the introduction of Google Pay, which has gained a constantly increasing market share globally - now counts more than 67m monthly users in India alone.

Google’s Cache project comes at a time when Alphabet, its parent company, is trying to step further into healthcare, with cloud computing and the planned acquisition of Fitbit. The partnership comes as giant tech rivals Facebook and Apple have already started to expand their presence in consumer finance trough Libra and Apple Pay, respectively. Also Jeff Bezos’ Amazon, before abandoning its effort due to concerns related to banking regulation, had entered into talks with banks (including JPMorgan) about offering checking accounts, according to a report from The Information. While mobile and online payments such as WeChat Pay and Alipay are already extremely popular in Asia, Silicon Valley companies have made far slower progress into the world of consumer finance, a broad area ranging from digital payment services to bank & brokerage accounts and loans.

Google’s Cache project comes at a time when Alphabet, its parent company, is trying to step further into healthcare, with cloud computing and the planned acquisition of Fitbit. The partnership comes as giant tech rivals Facebook and Apple have already started to expand their presence in consumer finance trough Libra and Apple Pay, respectively. Also Jeff Bezos’ Amazon, before abandoning its effort due to concerns related to banking regulation, had entered into talks with banks (including JPMorgan) about offering checking accounts, according to a report from The Information. While mobile and online payments such as WeChat Pay and Alipay are already extremely popular in Asia, Silicon Valley companies have made far slower progress into the world of consumer finance, a broad area ranging from digital payment services to bank & brokerage accounts and loans.

“We’re exploring how we can partner with banks and credit unions in the US to offer smart checking accounts through Google Pay, helping their customers benefit from useful insights and budgeting tools, while keeping their money in an FDIC or NCUA-insured account”, Google’s Craig Ewer said. Tech heavyweights see expansion into financial services as a way to diversify their source of revenues and strengthen relationships with their customers while also gaining valuable data. It is still unclear whether Google will charge fees for its checking accounts, and The Wall Street Journal told the company has yet to decide.

At the same time, tech companies are increasingly finding themselves under deep scrutiny from both lawmakers and regulators as they try to expand into new business models. Regulators and lawmakers' concerns are related especially to those companies’ poor track-record on data privacy and protection. Google said it has started talking with US regulators about compliance and regulatory issues related to the new project. In this respect, asked about Google’s project, US Senator Mark Warner told CNBC “There ought to be very strict scrutiny”. Confirming the US Investment Bank core role, Citi spokeswoman Liz Fogarty said: “Privacy and transparency are, and will continue to be, critical priorities”.

Through the partnership, Google might leverage on the regulatory and financial know-how of banks, without having to deal much with bank regulators. In fact, if as it seems deposits will still be stored in accounts managed by already regulated banks and if the lender will not provide Google with customers’ key financial data, regulatory license requirement might not arise at all. In addition, while Google provides its main services for free in exchange for customers' data, the company says it will not do the same with Google Pay related data. Tech companies' ambition might challenge existing financial services firms, already struggling from low interest rate environment and increasing compliance and capital requirements. However, Google seems determined to make allies, rather than enemies. In fact, according to The Wall Street Journal, the banks’ logo and brand will be front-and-center of the accounts, unlike Apple’s approach that intentionally branded its product first and foremost as an Apple product rather than a banking product. “Our approach is going to be to partner deeply with banks and the financial system” Google executive Caesar Sengupta said in an interview. “It may be the slightly longer path, but it’s more sustainable.” At the same time, the partnership shows how commercial banks are more than willing to pair up with tech companies in order to avoid being left out of the relationship. According to the partnership agreement, commercial banks will handle the majority of compliance requirements, activities that Google alone could not do without a proper license.

Capco partner Bryce Van Diver, who advised banks and payment companies commented: “We’re going to see more of this, but it’s not the death of banking. Compliance is still being managed by Citi. If you look at banks’ core competencies, compliance being one of those, they’re really good at that” – he continued - “This is probably more about Google Pay and how they plan to position that going forward to access all financial products, not just credit cards”. On the other hand, Citi commented: “This agreement has the potential to expand the reach and breadth of our customer base while complementing our continued investments in digital”. Checking accounts can be considered as a commodity product, however, they contain insightful data such as personal income, bill payments and consumer habits. Hence, for Google, the amount of data associated with accounts and payment services would represent another step in its constant path to collect information on all aspects of consumers’ habits. Therefore, Google will have to convince customers on its capability to protect personal data and show how it can be trusted with people's personal finances. Google added that it aims at bringing value to consumers, banks and merchants, with services that can include loyalty programs, but without selling checking-account users’ financial data.

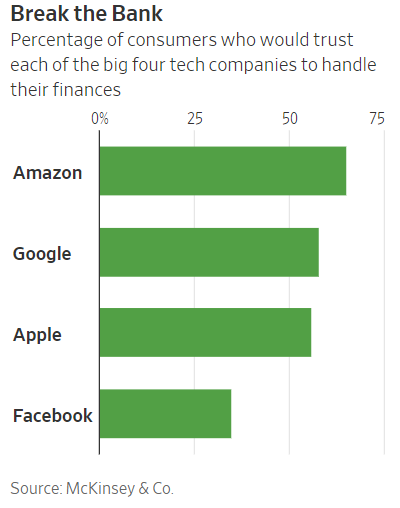

Looking at a recent survey conducted by McKinsey, about 58% of people declared they would trust financial products from Google. According to this survey, Google performed slightly better than Apple and significantly better than Facebook but worse than leading Amazon.

At the same time, tech companies are increasingly finding themselves under deep scrutiny from both lawmakers and regulators as they try to expand into new business models. Regulators and lawmakers' concerns are related especially to those companies’ poor track-record on data privacy and protection. Google said it has started talking with US regulators about compliance and regulatory issues related to the new project. In this respect, asked about Google’s project, US Senator Mark Warner told CNBC “There ought to be very strict scrutiny”. Confirming the US Investment Bank core role, Citi spokeswoman Liz Fogarty said: “Privacy and transparency are, and will continue to be, critical priorities”.

Through the partnership, Google might leverage on the regulatory and financial know-how of banks, without having to deal much with bank regulators. In fact, if as it seems deposits will still be stored in accounts managed by already regulated banks and if the lender will not provide Google with customers’ key financial data, regulatory license requirement might not arise at all. In addition, while Google provides its main services for free in exchange for customers' data, the company says it will not do the same with Google Pay related data. Tech companies' ambition might challenge existing financial services firms, already struggling from low interest rate environment and increasing compliance and capital requirements. However, Google seems determined to make allies, rather than enemies. In fact, according to The Wall Street Journal, the banks’ logo and brand will be front-and-center of the accounts, unlike Apple’s approach that intentionally branded its product first and foremost as an Apple product rather than a banking product. “Our approach is going to be to partner deeply with banks and the financial system” Google executive Caesar Sengupta said in an interview. “It may be the slightly longer path, but it’s more sustainable.” At the same time, the partnership shows how commercial banks are more than willing to pair up with tech companies in order to avoid being left out of the relationship. According to the partnership agreement, commercial banks will handle the majority of compliance requirements, activities that Google alone could not do without a proper license.

Capco partner Bryce Van Diver, who advised banks and payment companies commented: “We’re going to see more of this, but it’s not the death of banking. Compliance is still being managed by Citi. If you look at banks’ core competencies, compliance being one of those, they’re really good at that” – he continued - “This is probably more about Google Pay and how they plan to position that going forward to access all financial products, not just credit cards”. On the other hand, Citi commented: “This agreement has the potential to expand the reach and breadth of our customer base while complementing our continued investments in digital”. Checking accounts can be considered as a commodity product, however, they contain insightful data such as personal income, bill payments and consumer habits. Hence, for Google, the amount of data associated with accounts and payment services would represent another step in its constant path to collect information on all aspects of consumers’ habits. Therefore, Google will have to convince customers on its capability to protect personal data and show how it can be trusted with people's personal finances. Google added that it aims at bringing value to consumers, banks and merchants, with services that can include loyalty programs, but without selling checking-account users’ financial data.

Looking at a recent survey conducted by McKinsey, about 58% of people declared they would trust financial products from Google. According to this survey, Google performed slightly better than Apple and significantly better than Facebook but worse than leading Amazon.

From Citi’s point of view, the partnership might carry two main sources of risk. The first one is represented by regulatory risk, as the legislative pressure is likely to be heavier on privacy matters. The US bank will have to hope that regulators rely on Google’s quote that all personal information will be treated confidentially. The second risk is the threat that some analysts call “Apple risk”, meaning the possibility that Google could capture the most of the value out of the joint venture, following the consolidated Cupertino-based company tradition.

However, Citi might be willing to bear this risk because, when compared to other US megabank peers, it has a lower market penetration footprint in the US. As an example, Bank of America can rely on fourth times Citi’s US $186bn of retail deposits and is even able to pay almost a half for its deposit funding. Within this frame, the partnership might represent the right choice for Citi to gather deposits at a decent risk-reward tradeoff. The US lender has already spent the last year improving its digital banking platform, managing to gather more than $4bn in new deposits so far.

The open question is whether big tech will represent more a competitive threat or an interesting potential partner for banks. After all, a commercial bank can be considered as a union of a balance sheet, an info-system and a sales force. Silicon Valley companies seem willing to leave the regulated part (i.e. balance sheet) to banks, while targeting the remaining two aspects. The fact that tech companies are more interested in flirting with established financial institutions rather than trying to disrupt the banking industry as a whole, raises a flag on how complex and unattractive this business appears. If we consider that Alphabet (Google’s parent company) closed the last quarter with more than $120bn in cash and marketable securities, we can say that Google would not need external deposits to fund its project.

Instead of becoming a bank, Google is willing to leverage the history, brand, infrastructure and reputation of one of the world’s largest financial institution. Google is intending to use banks in order to create an ecosystem that could link payments, banking, identity and commerce credentials. If successful, Google would create an ecosystem that no other player has been able to produce at scale. A double-edged opportunity for customers, as aggregation of services increases value but so do concerns over data privacy, security and transparency.

However, Citi might be willing to bear this risk because, when compared to other US megabank peers, it has a lower market penetration footprint in the US. As an example, Bank of America can rely on fourth times Citi’s US $186bn of retail deposits and is even able to pay almost a half for its deposit funding. Within this frame, the partnership might represent the right choice for Citi to gather deposits at a decent risk-reward tradeoff. The US lender has already spent the last year improving its digital banking platform, managing to gather more than $4bn in new deposits so far.

The open question is whether big tech will represent more a competitive threat or an interesting potential partner for banks. After all, a commercial bank can be considered as a union of a balance sheet, an info-system and a sales force. Silicon Valley companies seem willing to leave the regulated part (i.e. balance sheet) to banks, while targeting the remaining two aspects. The fact that tech companies are more interested in flirting with established financial institutions rather than trying to disrupt the banking industry as a whole, raises a flag on how complex and unattractive this business appears. If we consider that Alphabet (Google’s parent company) closed the last quarter with more than $120bn in cash and marketable securities, we can say that Google would not need external deposits to fund its project.

Instead of becoming a bank, Google is willing to leverage the history, brand, infrastructure and reputation of one of the world’s largest financial institution. Google is intending to use banks in order to create an ecosystem that could link payments, banking, identity and commerce credentials. If successful, Google would create an ecosystem that no other player has been able to produce at scale. A double-edged opportunity for customers, as aggregation of services increases value but so do concerns over data privacy, security and transparency.

Francesco Spagnolo – 04/12/2019