Last year, Hong Kong skyrocketed to become the world’s ‘hottest’ IPO destination, hosting the initial offerings of 125 companies. However, there is the Dark side of the Moon.

On March 14th, a decade long story of alleged improper handlings of Hong Kong IPOs seemed to reach its conclusion. The Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) ruled that a group of banks were negligent in their duties as bookrunners and failed to conduct an adequate due diligence during the IPOs of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals. SFC, an authority responsible for the enforcement of securities market regulations in Hong Kong, imposed a fine totaling $100 million on UBS ($47.8 million), Morgan Stanley ($28.5 million), Merrill Lynch ($16.3 million), and Standard Chartered ($7.61 million). This article analyzes the cases of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals and attempts to draw similarities between them.

SFC is in a precarious position whereby it has to balance carefully between preserving Hong Kong’s attractiveness to Chinese companies and, at the same time, enforcing stricter accounting rules to combat the falsification and misreporting that have plagued a significant portion of the IPOs. Among them were the IPOs of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals. British Standard Chartered and Swiss UBS were mandated as joint bookrunners of China Forestry’s initial offering in 2009, which resulted in raising $216 million, whereas UBS, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch served as sponsors of Tianhe’s IPO that raised $654 million. However, both tickers were suspended within two years of respective IPOs after severe misreporting were uncovered. China Forestry was liquidated, whereas Tianhe’s shares are still suspended.

On the one hand, SFC, which is severely criticized as being too lenient towards accounting fraudulence, has taken steps to strengthen investor protection. Firstly, SFC has engineered legislation that allows the suspension of trading of shares of listed issuers whose accounting standards and published financial reports were deemed questionable. Secondly, in response to waves of bad floats, SFC ordered in 2013 that the investment banks acting as IPO sponsors would be held legally accountable for the information contained in the prospectuses. This decision, in fact, served as a foundation to the indictment of the aforementioned group of investment banks.

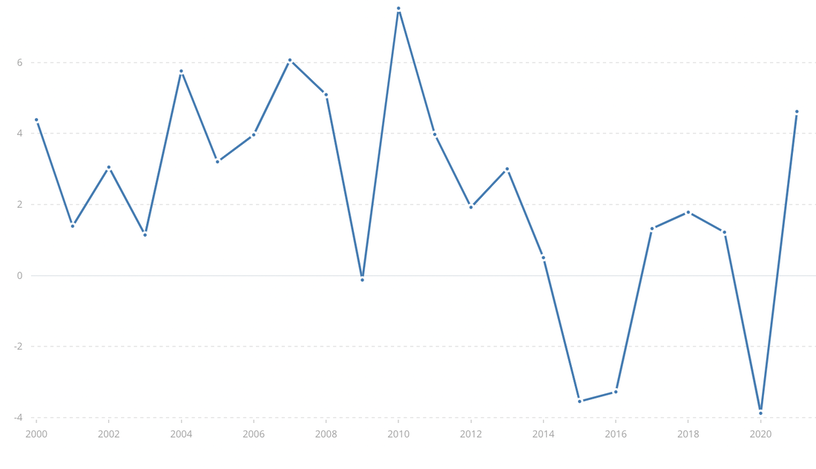

On the other hand, in an environment of stiff competition between stock exchanges, each additional regulation is tantamount to shooting oneself in the foot. In 2018, Hong Kong generated $36.3 billion in IPO proceeds, which was $7.4 billion more than New York. This 174% year-over-year increase in listings volume was primarily fueled by two ‘relaxations’ of the IPO regulations: approval of the listings by dual-class share structure issuers and by biotechnology companies that are yet to generate revenue. It is expected that Hong Kong will not be able to demonstrate the equivalent magnitude of initial offerings in 2019 due to the disappointing aftermarket performance and an overall decline of HKE in 2018.

On March 14th, a decade long story of alleged improper handlings of Hong Kong IPOs seemed to reach its conclusion. The Securities and Futures Commission (SFC) ruled that a group of banks were negligent in their duties as bookrunners and failed to conduct an adequate due diligence during the IPOs of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals. SFC, an authority responsible for the enforcement of securities market regulations in Hong Kong, imposed a fine totaling $100 million on UBS ($47.8 million), Morgan Stanley ($28.5 million), Merrill Lynch ($16.3 million), and Standard Chartered ($7.61 million). This article analyzes the cases of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals and attempts to draw similarities between them.

SFC is in a precarious position whereby it has to balance carefully between preserving Hong Kong’s attractiveness to Chinese companies and, at the same time, enforcing stricter accounting rules to combat the falsification and misreporting that have plagued a significant portion of the IPOs. Among them were the IPOs of China Forestry and Tianhe Chemicals. British Standard Chartered and Swiss UBS were mandated as joint bookrunners of China Forestry’s initial offering in 2009, which resulted in raising $216 million, whereas UBS, Morgan Stanley, and Merrill Lynch served as sponsors of Tianhe’s IPO that raised $654 million. However, both tickers were suspended within two years of respective IPOs after severe misreporting were uncovered. China Forestry was liquidated, whereas Tianhe’s shares are still suspended.

On the one hand, SFC, which is severely criticized as being too lenient towards accounting fraudulence, has taken steps to strengthen investor protection. Firstly, SFC has engineered legislation that allows the suspension of trading of shares of listed issuers whose accounting standards and published financial reports were deemed questionable. Secondly, in response to waves of bad floats, SFC ordered in 2013 that the investment banks acting as IPO sponsors would be held legally accountable for the information contained in the prospectuses. This decision, in fact, served as a foundation to the indictment of the aforementioned group of investment banks.

On the other hand, in an environment of stiff competition between stock exchanges, each additional regulation is tantamount to shooting oneself in the foot. In 2018, Hong Kong generated $36.3 billion in IPO proceeds, which was $7.4 billion more than New York. This 174% year-over-year increase in listings volume was primarily fueled by two ‘relaxations’ of the IPO regulations: approval of the listings by dual-class share structure issuers and by biotechnology companies that are yet to generate revenue. It is expected that Hong Kong will not be able to demonstrate the equivalent magnitude of initial offerings in 2019 due to the disappointing aftermarket performance and an overall decline of HKE in 2018.

An analysis of SFC’s investigation reports revealed that the quality of due diligence performed by UBS and Standard Chartered in the case of China Forestry could be described as ‘subpar’ at best, in fact, it was executed irresponsible. In particular, the joint sponsors committed egregious mistakes in examining the company’s assets, revenue streams, and customers.

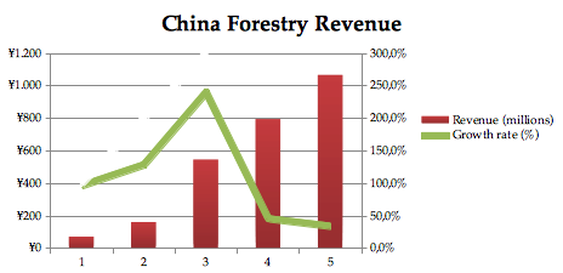

Although 70% of China Forestry’s revenue was obtained from a handful of customers domiciled in Yunnan, the same province where the company was located, the joint sponsors failed to arrange any face-to-face interviews, instead opting for only telephone surveys. Even more so, the banks did not administer any background checks of the purported customers or the people they had interviewed, neither had they obtained the telephone numbers themselves, but were given by China Forestry. This is considering the fact that the total revenue of China Forestry demonstrated an astonishing CAGR of 97.37% between 2006 and 2010, which was generated primarily by sales to the same small pool of consumers.

Secondly, UBS and Standard Chartered were similarly negligent in confirming the existence of the forestry assets and logging rights that China Forestry claimed to possess. The company declared in the prospectus that it owned forests of roughly 12,447 and 159,333 hectares in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, respectively, and certificates that allowed their logging. However, SFC established that the joint bookrunners did not visit the land and did not verify the presence of log production. Despite UBS and Standard Chartered claiming otherwise, they were not able to endorse their claims by any evidence or records of inspections. Instead, the banks either did not call any confirming inquiries into the documents presented by China Forestry, or delegated these tasks to third parties from Mainland China. Again, this is despite the CAGR of almost 20.38% in total sales volume of logs (m³), which one would assume to be suspicious.

Although 70% of China Forestry’s revenue was obtained from a handful of customers domiciled in Yunnan, the same province where the company was located, the joint sponsors failed to arrange any face-to-face interviews, instead opting for only telephone surveys. Even more so, the banks did not administer any background checks of the purported customers or the people they had interviewed, neither had they obtained the telephone numbers themselves, but were given by China Forestry. This is considering the fact that the total revenue of China Forestry demonstrated an astonishing CAGR of 97.37% between 2006 and 2010, which was generated primarily by sales to the same small pool of consumers.

Secondly, UBS and Standard Chartered were similarly negligent in confirming the existence of the forestry assets and logging rights that China Forestry claimed to possess. The company declared in the prospectus that it owned forests of roughly 12,447 and 159,333 hectares in Sichuan and Yunnan provinces, respectively, and certificates that allowed their logging. However, SFC established that the joint bookrunners did not visit the land and did not verify the presence of log production. Despite UBS and Standard Chartered claiming otherwise, they were not able to endorse their claims by any evidence or records of inspections. Instead, the banks either did not call any confirming inquiries into the documents presented by China Forestry, or delegated these tasks to third parties from Mainland China. Again, this is despite the CAGR of almost 20.38% in total sales volume of logs (m³), which one would assume to be suspicious.

One can observe an analogous failure to provide adequate due diligence and customer verification in the case of Tianhe Chemicals Group, when Morgan Stanley, Merrill Lynch, and UBS served as joint bookrunners. Even though ten customer interviews, both in person and by telephone, were arranged in total, the majority of them were never realized. The bookrunners were able to organize a meeting with Tianhe’s biggest customer at Tianhe’s headquarters. However, upon meeting with the representative of the alleged customer, he refused to identify himself, declined exchange business cards, and quickly retreated from the caucus.

Thus, it is surprising that the advising banks ignored the numerous red flags and ultimately decided to proceed with the IPOs. $100 million of fines paid by banks is only a minor part of the fallout of these catastrophic decisions. What the article has not discussed is the billions lost by investors deceived by fraud prospectuses. Can these investors really be consoled by SFC fining banks for their mishandlings after ten years? Not really.

Sultan Massalov

Sultan Massalov