The accelerating trend of globalization has transformed the Asian continent over the last decades from a largely underdeveloped region marked by the scars of colonial histories to a flourishing landscape with a number of thriving economies at the heart of global supply chains. Many Asian countries, most notably in East Asia, have moved from being pure commodity exporters or sources of cheap labor for Western companies, to being on the cutting edge of sophisticated technologies. While the trajectories were not synchronous, with Japan and Taiwan developing their semiconductors and computing expertise some time before China started supplying the world with virtually any industrial and consumer good you can think of, they have one factor in common: their economic development was primarily driven by cross-border trade rather than domestic demand. Since Asia’s economic progress is based so much on a global liberalized trading and supply chain system, it has incentivized governments to seek economic integration with their neighbors, their suppliers and export markets. Free-trade agreements (FTAs) and economic partnerships have evolved to facilitate Asia’s economic growth model. However, over recent years, several headwinds from the global rise of economic protectionism to geopolitical tensions have threatened to slow or even reverse this development. Therefore, in the following we will provide an overview of the current state of both bilateral and multilateral trade agreements in Asia and their further prospects.

Bilateral agreements enable destination countries establish a labor flow that fits the demands of employers and industrial sectors, while also improving management and increasing cultural linkages and interactions. These agreements provide countries of origin with continuous access to international labor markets as well as chances to improve workers' safety and welfare. Some examples of countries maintaining extensive bilateral trade agreements are:

1. The Republic of Korea - has memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with Myanmar, Timor-Leste, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand China, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, and Sri Lanka.

2. Malaysia — MOUs with Bangladesh, Viet Nam, China, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Pakistan and Indonesia to regulate recruitment processes and procedures.

3. Thailand — There are MOUs with Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Cambodia.

The Asia-Pacific region significantly contributes the most to the global network of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). There are 184 trade agreements in force, 19 that have been signed but are awaiting ratification, and 95 that are still being negotiated with at least one partner from the Asia-Pacific region (as of December 2020). The bulk of PTAs go well beyond goods liberalization, with 54 percent of all regionally implemented PTAs embracing both products and services.

1. The Republic of Korea - has memorandums of understanding (MOUs) with Myanmar, Timor-Leste, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Mongolia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand China, Indonesia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Viet Nam, and Sri Lanka.

2. Malaysia — MOUs with Bangladesh, Viet Nam, China, Sri Lanka, Thailand, Pakistan and Indonesia to regulate recruitment processes and procedures.

3. Thailand — There are MOUs with Lao People’s Democratic Republic, Myanmar and Cambodia.

The Asia-Pacific region significantly contributes the most to the global network of preferential trade agreements (PTAs). There are 184 trade agreements in force, 19 that have been signed but are awaiting ratification, and 95 that are still being negotiated with at least one partner from the Asia-Pacific region (as of December 2020). The bulk of PTAs go well beyond goods liberalization, with 54 percent of all regionally implemented PTAs embracing both products and services.

Bilateral PTAs make up roughly 78 percent of all PTAs currently in effect. Based on geographic coverage, 49 percent of all PTAs in the Asia-Pacific area are with nations from outside regions, confirming the premise that Asia-Pacific economies are currently engaged as dialogue partners both inside and outside the area.

In Asia there are several Trade Agreements (Free Trade Agreements and Economic Partnerships), both regional and extra-regional:

1. Intra-regional: ASEAN, South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Bay of Bengal Initiative (BIMSTEC), South Asian Free-Trade Area (SAFTA), Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO)

2. Extra-regional: Trans-Pacific Agreement, APEC, agreements with the European Union (EU)

3. Bilateral intra-regional: China-ASEAN, India-Korea

4. Bilateral extra-regional: China-Chile, Mexico-Japan

In Asia there are several Trade Agreements (Free Trade Agreements and Economic Partnerships), both regional and extra-regional:

1. Intra-regional: ASEAN, South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), Bay of Bengal Initiative (BIMSTEC), South Asian Free-Trade Area (SAFTA), Economic Cooperation Organisation (ECO)

2. Extra-regional: Trans-Pacific Agreement, APEC, agreements with the European Union (EU)

3. Bilateral intra-regional: China-ASEAN, India-Korea

4. Bilateral extra-regional: China-Chile, Mexico-Japan

Furthermore, digital trade issues are increasingly being included in PTAs by trade negotiators: E-commerce clauses are included within eight of the 17 trade agreements negotiated between 2019 and 2020. Digital Trade Agreements have also been struck by local economies, particularly Singapore (DTAs). The Japan-United States DTA was signed in 2019, and the Australia-Singapore Digital Economy Agreement (DEA) and the Chile-New Zealand-Singapore Digital Economy Partnership Agreement (DEPA) were both inked in 2020. More accords are on the way, particularly by Singapore, which is currently negotiating with the Republic of Korea and will begin negotiations with the United Kingdom in 2021.

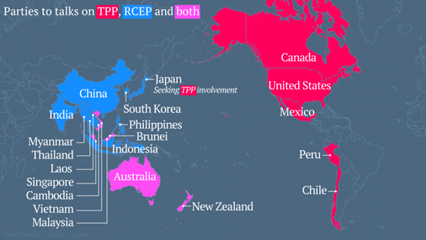

The longest-standing multilateral effort of economic integration is the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, or ASEAN. The group comprising ten Southeast Asian countries was founded by five members in 1967. Its current legal status and institutional framework are defined in the 2008 ASEAN Charter, widely seen as following the example of the European Union in setting objectives for integration. Beyond economic integration, ASEAN also promotes socio-cultural and political-security. The economic community, with a market size of $2.3 trillion and 600 million people, targets a reduction in barriers to trade, creating an attractive investment environment as well as a common approach to customs, standard-setting and intellectual property issues. Largely based on the 1992 AFTA agreement, it has not yet managed to create an economic union like the EU, as member states are still allowed to charge a limited amount of tariffs on goods and services imports from other members. Also, there is no common external tariff scheme. Still, ASEAN can be considered a major driver of economic integration even beyond its borders, as it signed several bilateral free trade and economic partnership agreements, for example with Korea, Japan, China, the United States and the EU. One of the most significant deals driven by ASEAN is the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, signed in 2020 together with China, Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand. Built on bilateral FTAs between ASEAN and the other signatories, it is the first FTA to connect the three East Asian, non-ASEAN members. Among other things, it covers trade in goods, and services, investment, economic and technical cooperation, intellectual property, competition, dispute settlement, e-commerce, and small and medium enterprises (SMEs). Especially the last point is interesting because it illustrates how these countries try to deepen economic engagement while protecting SMEs, which account for more than 90% of their business landscape, from the potentially destructive pressures of globalization.

Another important milestone in Asian trade liberalization is the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), comprising Australia, Brunei, Canada, Chile, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, New Zealand, Peru, Singapore, and Vietnam. Originally, the group, which represents 14% of the world economy, had worked on a similar deal called the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which fell apart after US President Donald Trump withdrew from the negotiations in 2017. While covering similar areas as the AFTA, ranging from the removal of trade barriers for most goods to investments, customs facilitation and intellectual property, it also extends to labor and environmental standards as well as an inclusive approach to trade, aiming to share the benefits of trade more widely. This is not least a reflection of the growing awareness about sustainability and human rights concerns, especially in developed economies. Membership in the CPTPP promises access to some of the fastest-growing markets in the world, and a number of countries have already expressed their interest in joining the pact. Earlier this year, the group has received applications from the United Kingdom, China and Taiwan. While the UK’s application represents an effort to expand its post-Brexit trading network, critics say that it would amount to little economic benefit for the country given the relatively low dependence on those markets. On the other hand, China’s request for admission has received a cold response after it had alienated important CPTPP members, especially Australia and Canada, over the last years by taking an aggressive foreign policy stance and weaponizing its trade policy on multiple occasions. Moreover, Japanese officials questioned whether China would be able to comply with the CPTPP’s strict rules on industrial subsidies and human rights.

On the other hand, there seems to be little economic integration between the ASEAN and CPTPP members and South Asia. This region had formed its own intergovernmental organization, the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) in 1985 already. In 2004, the group signed the agreement for the South Asian Free Trade Area (SAFTA), connecting Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka. The agreement is focused on a much narrower scope of issues than ASEAN or the CPTPP, including the reduction of tariffs and rules of origin but neglecting for example questions about intellectual property protection and sustainability. SAFTA is interesting in that it explicitly acknowledges the need to protect the so-called least-developed countries (LDCs) from the increased competition that comes with trade liberalization. The designation of countries as LDCs is derived from the list published by the United Nations, which currently includes Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan and Nepal. Under the FTA, these countries were granted more time for lower initial tariff reductions compared to non-LDCs, as well as longer lists of sensitive products which they wish to exclude from the tariff reduction scheme to protect the local economy. Therefore, it is reasonable to assume that the further progress of trade liberalization in this region will depend on the overall economic trajectory. These concerns for the treatment of LDCs within FTAs are especially likely to arise in any potential negotiations with developed countries.

To conclude, while Asia boasts an extensive network of both intraregional and extraregional bilateral PTAs, many countries gradually take steps to simplify this network by substituting sets of bilateral PTAs by multilateral equivalents within highly interconnected regions. The benefits of this simplification are apparent: increased transparency, collectively lower barriers to trade and thus more efficient markets. However, these multilateral initiatives are still often limited to a few economic blocs of economically similar and geographically closer countries. A major challenge when expanding such networks is the reconciliation of different political and economic models, often in the context of broader geopolitical disputes. For example, China is being viewed critically by its neighbors and their Western allies for its political system and foreign policy, and despite being one of their most important trading partners. Such disputes are likely to keep hindering the further liberalization of trade in Asia. In addition, wider trade agreements may be unsuitable to accommodate the special needs and interests of a variety of stakeholders. LDCs and markets dominated by SMEs may ask for special treatment to protect their businesses from tough global competition. To account for geopolitical frictions and the protection of idiosyncratic interests, and given their difficulties in expanding, existing trading blocs should try to deepen rather than broaden their relationships. As these economies mature, they should continue to push for more open common markets. The most promising candidates to achieve this are ASEAN and SAFTA, given the high similarity and interconnectedness between their respective members. Beyond that, it appears promising to follow the example of ASEAN when engaging with other markets, which uses its combined weight to achieve a more level playing field in bilateral negotiations with larger third parties such as China or the United States. In addition, bilateral agreements will continue to play an important role in the future as they allow for more selective approaches to trade liberalization while having the potential to grow into multilateral pacts later.