Climate change represents the biggest challenge that is awaiting us once the pandemic will be overcome. Indeed, it will be necessary to rebuild our economies to make them more sustainable. A clear example is the NextGenerationEU program adopted by the European Union. This project represents a €750 billion temporary recovery instrument to help repair the immediate economic and social damage brought by the Coronavirus pandemic and lay down the foundations for a green conversion of the European economy. However, even though the importance of climate change is now ascertained, in the last years few steps were made towards a way to fully measure its impact. Knowing the full climate exposure of firms and banking institutions is of utmost importance to solve the normative deadlock we are experiencing nowadays, where governments are still unsure whether it is worth or not implementing climate policies.

To solve this absence of a clear measurement, the ECB has decided to conduct a first-of-its-kind economy-wide climate stress test, covering approximately four million companies worldwide and 2,000 banks for a period of 30 years over the future. The project aims at assessing the overall exposure of the Euro area economy and financial system to future climate risk, represented by different climate scenarios.

What is climate risk?

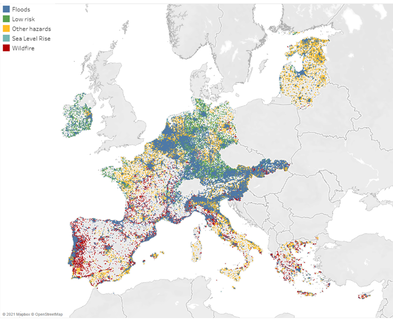

First, we have to understand how climate-related risk can affect the economy and the financial sector. Related to this, it is possible to identify two different categories of risk: the physical risk and the transition risk. Physical risk represents the actual possibility of damages to the economy caused by adverse climate-related events, such as changes in precipitation, ocean acidification, and rising sea level. These types of events can impact financial stability and economic growth through numerous demand and supply channels. Indeed, on the demand side, uncertainty about future scenarios can deeply damper household confidence and thus private consumption. Alternatively, on the supply side, weather-related events can damage properties and infrastructure. Physical risk also presents a high degree of variability across different countries and regions. The following chart represents good estimates of possible physical risk in the Eurozone.

To solve this absence of a clear measurement, the ECB has decided to conduct a first-of-its-kind economy-wide climate stress test, covering approximately four million companies worldwide and 2,000 banks for a period of 30 years over the future. The project aims at assessing the overall exposure of the Euro area economy and financial system to future climate risk, represented by different climate scenarios.

What is climate risk?

First, we have to understand how climate-related risk can affect the economy and the financial sector. Related to this, it is possible to identify two different categories of risk: the physical risk and the transition risk. Physical risk represents the actual possibility of damages to the economy caused by adverse climate-related events, such as changes in precipitation, ocean acidification, and rising sea level. These types of events can impact financial stability and economic growth through numerous demand and supply channels. Indeed, on the demand side, uncertainty about future scenarios can deeply damper household confidence and thus private consumption. Alternatively, on the supply side, weather-related events can damage properties and infrastructure. Physical risk also presents a high degree of variability across different countries and regions. The following chart represents good estimates of possible physical risk in the Eurozone.

A second climate-related risk is the so-called transition risk, which attains all the costs necessary to shift to a low-carbon economy. Quite intuitively, these costs will be higher for the industries more reliant on carbon and other fossil fuels. Furthermore, the adjustment process is likely to have a bigger impact on the economy when the necessary climate policies will be implemented in an unexpected and overall disorderly way.

Finally, it is easy to see that the two types of risk are not independent. Indeed, a lack of a coordinated and sufficiently strong intervention may drastically increase the future physical risk. On the other hand, early action can mitigate future disruptions of the economy and the financial system but will represent a higher initial cost.

Stress tests: a way to evaluate risk

After the Great financial crisis, stress tests have become widely used to conduct a detailed analysis of the solvency and the resilience of financial intermediaries. Without diving in too deep into the explanation, which is not the main task of this article, a bank stress test utilizes hypothetical scenarios designed to determine whether a bank has sufficient capital to withstand negative shocks. Generally speaking, these scenarios represent deep recessions or financial market crashes, and in such a way it is possible to understand how the financial system may be impacted in a worst-case scenario. Climate stress tests, like the one the ECB is conducting, have the same objective: test how the financial sector and other non-financial firms might be impacted in different climate scenarios. While conventional stress tests focus on areas like credit risk, market risk, and liquidity risk to measure the financial health of intermediaries, the climate stress test will also consider physical and transition risk.

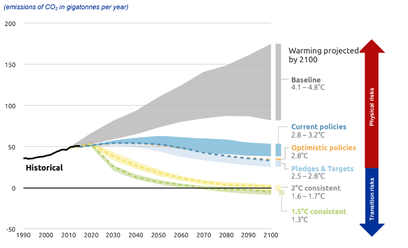

At the foundation of a good stress test, there are the climate risk scenarios we want to consider. On this note, the ECB and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) suggest that there are at least four different global warming routes that have to be considered. The first is the baseline, characterized by the absence of climate policies. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, this outcome would result in an increase in temperature by 2100 of 4.1-4.8°C. A second scenario reflects the current policies implemented which will lead to a warming of 3.2°C. An additional third scenario considers the optimistic policies raised by institutions, but not yet implemented, resulting in an overall increase of the temperature of 2.8°C. The fourth and final scenario allows instead for the full implementation of all the policies necessary to reach the goal of maintaining the increase in temperature below 2°C.

Finally, it is easy to see that the two types of risk are not independent. Indeed, a lack of a coordinated and sufficiently strong intervention may drastically increase the future physical risk. On the other hand, early action can mitigate future disruptions of the economy and the financial system but will represent a higher initial cost.

Stress tests: a way to evaluate risk

After the Great financial crisis, stress tests have become widely used to conduct a detailed analysis of the solvency and the resilience of financial intermediaries. Without diving in too deep into the explanation, which is not the main task of this article, a bank stress test utilizes hypothetical scenarios designed to determine whether a bank has sufficient capital to withstand negative shocks. Generally speaking, these scenarios represent deep recessions or financial market crashes, and in such a way it is possible to understand how the financial system may be impacted in a worst-case scenario. Climate stress tests, like the one the ECB is conducting, have the same objective: test how the financial sector and other non-financial firms might be impacted in different climate scenarios. While conventional stress tests focus on areas like credit risk, market risk, and liquidity risk to measure the financial health of intermediaries, the climate stress test will also consider physical and transition risk.

At the foundation of a good stress test, there are the climate risk scenarios we want to consider. On this note, the ECB and the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB) suggest that there are at least four different global warming routes that have to be considered. The first is the baseline, characterized by the absence of climate policies. According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, this outcome would result in an increase in temperature by 2100 of 4.1-4.8°C. A second scenario reflects the current policies implemented which will lead to a warming of 3.2°C. An additional third scenario considers the optimistic policies raised by institutions, but not yet implemented, resulting in an overall increase of the temperature of 2.8°C. The fourth and final scenario allows instead for the full implementation of all the policies necessary to reach the goal of maintaining the increase in temperature below 2°C.

As with the traditional stress test, each scenario is represented by a different degree of riskiness and thus will impact non-financial institutions and banks differently. The baseline scenario is characterized by low transition risks, but a higher degree of physical risk caused by the worsening of global warming. On the other hand, the higher the number of climate policies that will be implemented the lower will be the future risk of strongly adverse climate events, but the higher will be the immediate transition costs.

Preliminary results and conclusion

The preliminary analysis conducted by the ECB using in-house data represents an important step forward in the measurement and quantification of climate risk. In particular, the main results concern the Eurozone firms’ default probabilities. A disorderly transition to a cleaner economy is characterized by always higher probabilities of default over the next 30 years, even though in the immediate term firms will suffer less. Therefore, even though there is still room for improvement, for instance by better considering the response of banks for example to a decline in creditworthiness of borrowers caused by climate adverse events, it is now clear that there are evident benefits in acting immediately. The short-term costs will always be relatively less than the potentially higher cost caused by natural disasters in the medium/long term. It is thus now clear that climate change has to be considered as a major source of systemic risk.

While this first analysis is important because of its new findings, first and foremost it must be considered a starting point, a new way to help redefine questions and methodologies that can address the gaps we currently have in the formal quantification of climate risk.

Simone Boldrini

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

Preliminary results and conclusion

The preliminary analysis conducted by the ECB using in-house data represents an important step forward in the measurement and quantification of climate risk. In particular, the main results concern the Eurozone firms’ default probabilities. A disorderly transition to a cleaner economy is characterized by always higher probabilities of default over the next 30 years, even though in the immediate term firms will suffer less. Therefore, even though there is still room for improvement, for instance by better considering the response of banks for example to a decline in creditworthiness of borrowers caused by climate adverse events, it is now clear that there are evident benefits in acting immediately. The short-term costs will always be relatively less than the potentially higher cost caused by natural disasters in the medium/long term. It is thus now clear that climate change has to be considered as a major source of systemic risk.

While this first analysis is important because of its new findings, first and foremost it must be considered a starting point, a new way to help redefine questions and methodologies that can address the gaps we currently have in the formal quantification of climate risk.

Simone Boldrini

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.