In an economic backdrop governed by market instability, soaring rates, and all the worrying signs that

point to an impending recession, the UK needed a talented leader to steer the ship away from the storm.

Unfortunately, in her 45-day tenure, Boris Johnsons’ successor, Liz Truss, not only failed to better the

situation, but managed to create a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Truss is now held accountable for

the stained reputation of the Tory Party, the worse-than-ever economic situation of the nation, and the

general lack of trust of the rest of the world in UK politics.

The “mini-budget” and its faulty premises

Soon after taking office due to her victorious leadership race, the Conservative leader appointed Kwasi

Kwarteng as her chancellor. Together, they announced on the 23rd of September 2022 the biggest tax

reform since 1972 called “The Growth Plan”. This ambitious fiscal policy eyed a reduction of 1% in personal

tax for middle incomes and the abolition of the 45% top rate of income tax for the people that earn more

than £150,000 annually, cumulating to a £45bn deficit. Despite her known advocacy for free-market

policies, these announcements were a far outreach from the plans that gained her popularity during the

campaign. The reason behind the Growth Plan was to inject money into the economy, thus increasing

public spending, and company revenues. Though it initially seen some praise from conservative party

members and free-market supporters, the mini budget was violating simple macroeconomic principles

and was doomed to failure.

Governments have little headway when it comes to controlling inflation, such as implementing

Contractionary Monetary Policies, controlling prices, or raising borrowing costs that prevent excess

supply. The latter often takes its toll on low to middle income people, rather than the upper classes, yet

it is still one of the most effective measures to combat declines in a currency’s buying power. Plans to

bring down inflation to 2% from the 40-year high of 8% were already underway, with the several interest

rates hikes that the Bank of England announced during late Summer and the beginning of Fall. Therefore,

the timing of the radical tax couldn’t be worse, and if it went into practice, it would’ve undermined all

previous efforts to mend the cost-of-living crisis. The marginal benefit that an average UK citizen would

gain was outweighed by the potential 4-digit increase in annual mortgage costs, and Truss’s budget earned

the nickname of “Robin Hood in Reverse” (Frances O’Grady, TUC general secretary).

As Wall Street Journal best puts it, the outcome of Truss’ actions transformed the United Kingdom into a

high inflation, high tax, low growth economy – quite the opposite to her initial agenda. The current global

market conditions are far from being the only culprit for the disastrous consequences of her fiscal policy.

To better understand what exacerbated the shockwave created by the tax cut, we would have to look at

pension funds and their rather unique mechanism in the UK.

What are pension funds

Pension funds are financial intermediaries which collect money from insured people, invest it in long-term

assets and provide them with income following their retirement.

Despite regulations are vastly different across countries, there are two main kinds of pension funds:

defined contribution and defined benefit.

While in the former case the policyholder makes contributions to the fund and receives money depending

on the performance of the fund, in the latter case the future benefit is defined or, at least, guaranteed for

a minimum amount.

What is LDI and its biggest drawback

Defined Benefit (DB) pension funds need to make sure that their assets can generate enough cash to meet

their liabilities, namely the monthly benefit guaranteed to pensioners.

Consequently, they use a well-known investing strategy, called Liability Driven Investment (LDI).

A pension fund that uses the LDI strategy must focus on the asset side to invest in a manner that provides

the necessary return to cover all future assurances, paying attention to inflation and risk from liabilities.

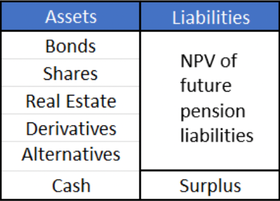

It is useful to focus on the composition of a typical pension fund’s balance sheet to better understand

their biggest risk:

point to an impending recession, the UK needed a talented leader to steer the ship away from the storm.

Unfortunately, in her 45-day tenure, Boris Johnsons’ successor, Liz Truss, not only failed to better the

situation, but managed to create a crisis of unprecedented proportions. Truss is now held accountable for

the stained reputation of the Tory Party, the worse-than-ever economic situation of the nation, and the

general lack of trust of the rest of the world in UK politics.

The “mini-budget” and its faulty premises

Soon after taking office due to her victorious leadership race, the Conservative leader appointed Kwasi

Kwarteng as her chancellor. Together, they announced on the 23rd of September 2022 the biggest tax

reform since 1972 called “The Growth Plan”. This ambitious fiscal policy eyed a reduction of 1% in personal

tax for middle incomes and the abolition of the 45% top rate of income tax for the people that earn more

than £150,000 annually, cumulating to a £45bn deficit. Despite her known advocacy for free-market

policies, these announcements were a far outreach from the plans that gained her popularity during the

campaign. The reason behind the Growth Plan was to inject money into the economy, thus increasing

public spending, and company revenues. Though it initially seen some praise from conservative party

members and free-market supporters, the mini budget was violating simple macroeconomic principles

and was doomed to failure.

Governments have little headway when it comes to controlling inflation, such as implementing

Contractionary Monetary Policies, controlling prices, or raising borrowing costs that prevent excess

supply. The latter often takes its toll on low to middle income people, rather than the upper classes, yet

it is still one of the most effective measures to combat declines in a currency’s buying power. Plans to

bring down inflation to 2% from the 40-year high of 8% were already underway, with the several interest

rates hikes that the Bank of England announced during late Summer and the beginning of Fall. Therefore,

the timing of the radical tax couldn’t be worse, and if it went into practice, it would’ve undermined all

previous efforts to mend the cost-of-living crisis. The marginal benefit that an average UK citizen would

gain was outweighed by the potential 4-digit increase in annual mortgage costs, and Truss’s budget earned

the nickname of “Robin Hood in Reverse” (Frances O’Grady, TUC general secretary).

As Wall Street Journal best puts it, the outcome of Truss’ actions transformed the United Kingdom into a

high inflation, high tax, low growth economy – quite the opposite to her initial agenda. The current global

market conditions are far from being the only culprit for the disastrous consequences of her fiscal policy.

To better understand what exacerbated the shockwave created by the tax cut, we would have to look at

pension funds and their rather unique mechanism in the UK.

What are pension funds

Pension funds are financial intermediaries which collect money from insured people, invest it in long-term

assets and provide them with income following their retirement.

Despite regulations are vastly different across countries, there are two main kinds of pension funds:

defined contribution and defined benefit.

While in the former case the policyholder makes contributions to the fund and receives money depending

on the performance of the fund, in the latter case the future benefit is defined or, at least, guaranteed for

a minimum amount.

What is LDI and its biggest drawback

Defined Benefit (DB) pension funds need to make sure that their assets can generate enough cash to meet

their liabilities, namely the monthly benefit guaranteed to pensioners.

Consequently, they use a well-known investing strategy, called Liability Driven Investment (LDI).

A pension fund that uses the LDI strategy must focus on the asset side to invest in a manner that provides

the necessary return to cover all future assurances, paying attention to inflation and risk from liabilities.

It is useful to focus on the composition of a typical pension fund’s balance sheet to better understand

their biggest risk:

As shown in the picture, pension funds invest a portion of their assets in liability-matching bonds and a

portion in growth assets such as corporate credit, equities, real estate. They then hedge the risks of that

strategy with derivatives, using bond assets as collateral.

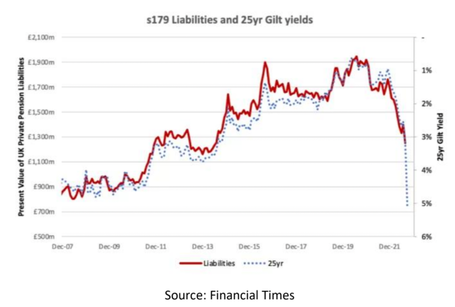

The problem arises as interest rates change: if they drop, as was the case in the past decade due to

accommodative policies by central banks, the NPV of future pension liabilities rises due to the lowest

discount factor and the defined benefit pension fund must ensure that its assets rise accordingly.

However, while NPV of future liabilities rise, some assets (like stocks) might not immediately appreciate,

worsening its accounting statements and surplus.

The regulator estimates that every 10 base points fall in UK gilt yields increases UK scheme liabilities by

£23.7bn, causing that in the last decade the scheme liabilities increased by £960bn (about 40% of the

GDP). However, the increase in the interest rates experienced from the end of 2020 led more than a third

of UK DB pension schemes from deficit to surplus, improving the pension funding by £350bn.

portion in growth assets such as corporate credit, equities, real estate. They then hedge the risks of that

strategy with derivatives, using bond assets as collateral.

The problem arises as interest rates change: if they drop, as was the case in the past decade due to

accommodative policies by central banks, the NPV of future pension liabilities rises due to the lowest

discount factor and the defined benefit pension fund must ensure that its assets rise accordingly.

However, while NPV of future liabilities rise, some assets (like stocks) might not immediately appreciate,

worsening its accounting statements and surplus.

The regulator estimates that every 10 base points fall in UK gilt yields increases UK scheme liabilities by

£23.7bn, causing that in the last decade the scheme liabilities increased by £960bn (about 40% of the

GDP). However, the increase in the interest rates experienced from the end of 2020 led more than a third

of UK DB pension schemes from deficit to surplus, improving the pension funding by £350bn.

Given the risk of a fall in interest rates, hedging is usually involved in LDI, as pension funds tend to invest

in Bonds with a similar maturity to their liabilities to minimize their risk.

However, due to decreasing bond returns over the past decade, pension funds have increasingly used a

more efficient instrument: Interest Rate Swaps.

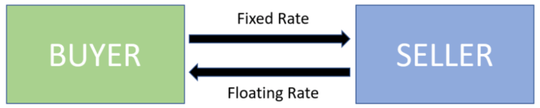

Interest rate Swaps

An Interest Swap is a forward contract where one institution, by convention termed Buyer (or Payer), pays

a fixed rate on a notional amount in exchange for an adjustable rate by a Seller (or Receiver).

in Bonds with a similar maturity to their liabilities to minimize their risk.

However, due to decreasing bond returns over the past decade, pension funds have increasingly used a

more efficient instrument: Interest Rate Swaps.

Interest rate Swaps

An Interest Swap is a forward contract where one institution, by convention termed Buyer (or Payer), pays

a fixed rate on a notional amount in exchange for an adjustable rate by a Seller (or Receiver).

More than 62% of the DB pension funds use Interest Rate Swaps as “Receivers” to protect themselves

from a drop in rates, acting as a hedge without using capital that can thus be invested in other activities

to implement the maturity-matching strategy, except for a small margin to be paid to the clearing houses.

As a matter of fact, in these derivative contracts, the notional capital itself is never paid but it is only used

as a reference measure to compute the interests to pay/receive. The plan was that losses from the IRS

should match the declining scheme liability values.

Drop in UK bonds and Margin Calls

That way, if rates fall, the portfolio value rises to match the increasing value of your liabilities so that you

are hedged. Everything seemed to be great, until the mini-budget was unveiled:

from a drop in rates, acting as a hedge without using capital that can thus be invested in other activities

to implement the maturity-matching strategy, except for a small margin to be paid to the clearing houses.

As a matter of fact, in these derivative contracts, the notional capital itself is never paid but it is only used

as a reference measure to compute the interests to pay/receive. The plan was that losses from the IRS

should match the declining scheme liability values.

Drop in UK bonds and Margin Calls

That way, if rates fall, the portfolio value rises to match the increasing value of your liabilities so that you

are hedged. Everything seemed to be great, until the mini-budget was unveiled:

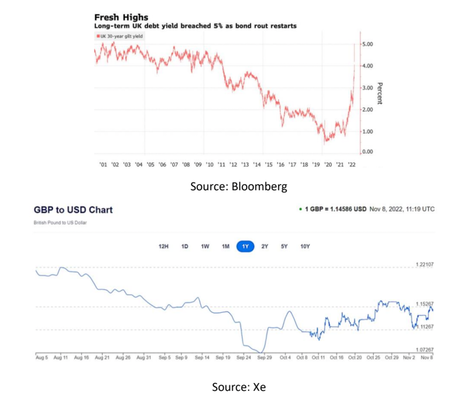

When Minister Kwarteng unveiled his deficit-financed fiscal plan, the market thought it illogical and

aggressively sold off Gilts, which had already suffered a sharp decline following BOE's attempt to fight

inflation. The pound tumbled against the dollar sinking to its lowest point ever on the September 26th at

1.0384, even lower than the levels of February 1985.

The fiscal policy and the subsequent market reaction affected immediately the condition of the pension

funds. While pensioners and workers usually cannot withdraw their money from pensions funds, banks

and clearing houses have the right to ask for higher security margins on interest rate swaps to protect

themselves against high-volatility market movements.

By the end of September, the number of margin calls was £170 billion and pension funds (who manage

£1.5 Trillion in the UK) could sell high liquidity financial instruments (Gilts) to quickly meet those huge

demands. Moreover, the sale of other growth assets, such as equities and credit, which also fell in value,

did not help them raise a sufficient level of liquidity.

However, the heavy and sudden sale of the Gilts worsened the situation: the sharp fall in the government

bond prices generated a consequent reduction in the assets of the pension funds and triggered new

rounds of margin calls. Furthermore, the counterparties of the IRS have the power of simply liquidating

all the collateral posted and closing the position, and these measures would have created big issues given

that the main eligible collateral of pension funds are long Gilts. This vicious circle would have led to the

failure of much of the English pension system without emergency intervention. An upper end estimate

stated that if LDI was implemented entirely through derivatives, the total collateral call would have been

over £380bn: a huge disaster. “At some point this morning I was worried this was the beginning of the

end" said a senior London-based banker, adding that at one point there were no long-term UK gilts buyers.

The short-term liquidity rush by pension funds in the UK had also systemic effects on the asset

management industry because the defined-benefit pension schemes are the major investors in UK

institutional real estate funds. They invest also in illiquid assets because of two main reasons: they have a

longer time horizon and, differently from banks, they are not subject to sudden withdrawals of money

(bank runs). Pension funds have been rapidly selling a broad range of assets to meet demands for

collateral and, for this reason, the asset managers were forced to impose “gates” to prevent investors

from making withdrawals and reduce their need to fire sale assets. Therefore, Schroders, BlackRock and

Columbia Threadneedle had to impose restrictions on redemptions from institutional real estate funds,

which were already struggling in the last year because of the increasing liquidity preferences due to the

uncertainty in the markets.

BoE intervention

The BoE stepped in on 28th of September after being warned by investment banks and fund managers

that the collateral requirements could trigger a Gilts collapse, according to a person familiar with the BoE.

The central bank stressed that it was not looking for lower long-term rates. Instead, it wanted to prevent

a downward spiral in which pension funds had to sell gilts to meet security margins required by investment

banks to maintain their IRS positions.

The BoE reacted as lender of last resort, putting £65 billion (£5bn for 13 days) on the table to buy long-

term bonds, in addition to other financial instruments to inject immediate liquidity into the system.

Long term rates (30Y) collapsed from above 5% on the 27th of September to less than 3.75% on the 3

rd of

October, inverting their strong uptrend: “If there was no intervention today, gilts yields could have gone

up to 7-8% from 4.5% this morning and in that situation around 90% of UK pensions funds would have run

out of collateral, they would have been wiped out”, declared Kerrin Rosenberg, Cardano Investment chief

executive.

Credibility

The market turmoil generated by Liz Truss fiscal policies made her lose political credibility, particularly

because of the market orientation of the institutional environment of the United Kingdom. After less than

two months from her election, she decided to resign from the Prime Minister role and was substituted by

Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Boris Johnson government. Bizarrely, he is the member

of the Tory party who was defeated by Truss in the Conservative leadership race: he lost the battle but

seems to have won the war, at least for now. His government members, like the new Chancellor of the

Exchequer Jeremy Hunt seem to be competent and determined to implement orthodox and responsible

fiscal policies. Indeed, in the short term the market reacted positively to his election: the yield of Gilts

dropped, and the pound strengthened. However, in the medium-long term Sunak’s government has to

face a complicated economic situation and big structural problems: the terrible state of public services

such as the National Health Service, which will also worsen in the winter and the schools, which are

suffering because of the public spending cuts due to inflation. Furthermore, UK has to deal with a £25bn

hole in public finances and with the emergency of energy prices (which are expected to double). The new

government must also fight, above all, against the risk of a recession, which is likely to occur if Sunak really

implementsrestrictive fiscal policies together with the inevitable interest rate hikes from the BoE. Overall,

this situation is not easy to tackle from a country which has not yet recovered from the costs of the Brexit

and, above all, from a government which has not got a democratic legitimacy. Sunak’s task will be hard

also from a political point of view: he will have to resist the voters’ demands for general elections and deal

with the consequences of his policies in terms of unpopularity.

Moreover, also the British central bank suffered in terms of credibility because, caring about short-term

shocks, it lost sight of its actual mandate of macro stabilization of the business cycles in the medium term.

Indeed, these expansionary policies may lead to higher levels of inflation expectations and inflation itself,

the same urgency the BoE was trying to defeat through many interest rate hikes. The level of credibility

of the BoE was also jeopardized by the news of the possible extension of the bond purchase program for

a longer time. However, the BoE regained greater authority by deciding not to extend the bond buying

program later than the intended date (October 14th). Other positive signals of credibility come from the

Gilts market, which returned to the pre-crisis level also thanks to the more conservative approach

presented by the new fiscal plan of the Sunak government. Furthermore, Sarah Breeden, BoE executive

director for financial stability, is urging banks to improve their financial counterparty risk assessments to

prevent instability in the financial system.

Sunak’s government and BoE will also be required to solve the current problems of the pension funds.

Although the intervention by the Bank of England has since stabilized the Gilts market, pension schemes

have continued to face collateral calls, accentuated by the new, more conservative stance from banks and

asset managers. If they were to run out of liquid assets that could be used to top up collateral in their LDI

strategies, a solution for pension funds could be accepting lower levels of hedging. Another interesting

point is that LDI is popular also in the United States: might they face a similar risk in the future? It seems

that in the US the risk of replicating the UK story is lower because their pension funds tend to use less

leverage than their UK peers.

These events also show how the legal independence of central banks does not in fact always translate

into their actual independence. The BoE has proven to be de-facto dependent on the measures taken by

the British government. The other crucial factor will be chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement on

November 17. If the government proceeds with immediate public spending cuts and tax increases to fill a

gaping hole in the public finances, it will depress the economy further and ease the pressure on the BoE

to raise interest rates. The narrative of a central bank constrained by politics has also been confirmed by

Ben Broadbent, the BoE deputy governor, who stated that the next fiscal actions of the government would

influence the BoE decisions.

Conclusions

All in all, Liz Truss' imprudent fiscal policies had negative economic, financial and political consequences

in the short term. From an economic perspective, the government announcements may have

undermined the BoE efforts to contrast the increasing inflation. On financial markets, the pension funds

disaster revealed a structural weakness of the hedging interest rate risk using derivative instruments

such as the IRS. At last, the story of the Truss government was nothing but a perfect example of political

debacle which led to shortest government in the UK history and, as a result, to a consequent loss in the

credibility of the British institutions. Fortunately, the new government of Rishi Sunak seems to be

determined to face the major challenges of a country in severe economic difficulties and to restore the

historical authority of the national institutions.

By Ernesto Bardi, Lorenzo Moretti, Matei Sandru

aggressively sold off Gilts, which had already suffered a sharp decline following BOE's attempt to fight

inflation. The pound tumbled against the dollar sinking to its lowest point ever on the September 26th at

1.0384, even lower than the levels of February 1985.

The fiscal policy and the subsequent market reaction affected immediately the condition of the pension

funds. While pensioners and workers usually cannot withdraw their money from pensions funds, banks

and clearing houses have the right to ask for higher security margins on interest rate swaps to protect

themselves against high-volatility market movements.

By the end of September, the number of margin calls was £170 billion and pension funds (who manage

£1.5 Trillion in the UK) could sell high liquidity financial instruments (Gilts) to quickly meet those huge

demands. Moreover, the sale of other growth assets, such as equities and credit, which also fell in value,

did not help them raise a sufficient level of liquidity.

However, the heavy and sudden sale of the Gilts worsened the situation: the sharp fall in the government

bond prices generated a consequent reduction in the assets of the pension funds and triggered new

rounds of margin calls. Furthermore, the counterparties of the IRS have the power of simply liquidating

all the collateral posted and closing the position, and these measures would have created big issues given

that the main eligible collateral of pension funds are long Gilts. This vicious circle would have led to the

failure of much of the English pension system without emergency intervention. An upper end estimate

stated that if LDI was implemented entirely through derivatives, the total collateral call would have been

over £380bn: a huge disaster. “At some point this morning I was worried this was the beginning of the

end" said a senior London-based banker, adding that at one point there were no long-term UK gilts buyers.

The short-term liquidity rush by pension funds in the UK had also systemic effects on the asset

management industry because the defined-benefit pension schemes are the major investors in UK

institutional real estate funds. They invest also in illiquid assets because of two main reasons: they have a

longer time horizon and, differently from banks, they are not subject to sudden withdrawals of money

(bank runs). Pension funds have been rapidly selling a broad range of assets to meet demands for

collateral and, for this reason, the asset managers were forced to impose “gates” to prevent investors

from making withdrawals and reduce their need to fire sale assets. Therefore, Schroders, BlackRock and

Columbia Threadneedle had to impose restrictions on redemptions from institutional real estate funds,

which were already struggling in the last year because of the increasing liquidity preferences due to the

uncertainty in the markets.

BoE intervention

The BoE stepped in on 28th of September after being warned by investment banks and fund managers

that the collateral requirements could trigger a Gilts collapse, according to a person familiar with the BoE.

The central bank stressed that it was not looking for lower long-term rates. Instead, it wanted to prevent

a downward spiral in which pension funds had to sell gilts to meet security margins required by investment

banks to maintain their IRS positions.

The BoE reacted as lender of last resort, putting £65 billion (£5bn for 13 days) on the table to buy long-

term bonds, in addition to other financial instruments to inject immediate liquidity into the system.

Long term rates (30Y) collapsed from above 5% on the 27th of September to less than 3.75% on the 3

rd of

October, inverting their strong uptrend: “If there was no intervention today, gilts yields could have gone

up to 7-8% from 4.5% this morning and in that situation around 90% of UK pensions funds would have run

out of collateral, they would have been wiped out”, declared Kerrin Rosenberg, Cardano Investment chief

executive.

Credibility

The market turmoil generated by Liz Truss fiscal policies made her lose political credibility, particularly

because of the market orientation of the institutional environment of the United Kingdom. After less than

two months from her election, she decided to resign from the Prime Minister role and was substituted by

Rishi Sunak, the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the Boris Johnson government. Bizarrely, he is the member

of the Tory party who was defeated by Truss in the Conservative leadership race: he lost the battle but

seems to have won the war, at least for now. His government members, like the new Chancellor of the

Exchequer Jeremy Hunt seem to be competent and determined to implement orthodox and responsible

fiscal policies. Indeed, in the short term the market reacted positively to his election: the yield of Gilts

dropped, and the pound strengthened. However, in the medium-long term Sunak’s government has to

face a complicated economic situation and big structural problems: the terrible state of public services

such as the National Health Service, which will also worsen in the winter and the schools, which are

suffering because of the public spending cuts due to inflation. Furthermore, UK has to deal with a £25bn

hole in public finances and with the emergency of energy prices (which are expected to double). The new

government must also fight, above all, against the risk of a recession, which is likely to occur if Sunak really

implementsrestrictive fiscal policies together with the inevitable interest rate hikes from the BoE. Overall,

this situation is not easy to tackle from a country which has not yet recovered from the costs of the Brexit

and, above all, from a government which has not got a democratic legitimacy. Sunak’s task will be hard

also from a political point of view: he will have to resist the voters’ demands for general elections and deal

with the consequences of his policies in terms of unpopularity.

Moreover, also the British central bank suffered in terms of credibility because, caring about short-term

shocks, it lost sight of its actual mandate of macro stabilization of the business cycles in the medium term.

Indeed, these expansionary policies may lead to higher levels of inflation expectations and inflation itself,

the same urgency the BoE was trying to defeat through many interest rate hikes. The level of credibility

of the BoE was also jeopardized by the news of the possible extension of the bond purchase program for

a longer time. However, the BoE regained greater authority by deciding not to extend the bond buying

program later than the intended date (October 14th). Other positive signals of credibility come from the

Gilts market, which returned to the pre-crisis level also thanks to the more conservative approach

presented by the new fiscal plan of the Sunak government. Furthermore, Sarah Breeden, BoE executive

director for financial stability, is urging banks to improve their financial counterparty risk assessments to

prevent instability in the financial system.

Sunak’s government and BoE will also be required to solve the current problems of the pension funds.

Although the intervention by the Bank of England has since stabilized the Gilts market, pension schemes

have continued to face collateral calls, accentuated by the new, more conservative stance from banks and

asset managers. If they were to run out of liquid assets that could be used to top up collateral in their LDI

strategies, a solution for pension funds could be accepting lower levels of hedging. Another interesting

point is that LDI is popular also in the United States: might they face a similar risk in the future? It seems

that in the US the risk of replicating the UK story is lower because their pension funds tend to use less

leverage than their UK peers.

These events also show how the legal independence of central banks does not in fact always translate

into their actual independence. The BoE has proven to be de-facto dependent on the measures taken by

the British government. The other crucial factor will be chancellor Jeremy Hunt’s autumn statement on

November 17. If the government proceeds with immediate public spending cuts and tax increases to fill a

gaping hole in the public finances, it will depress the economy further and ease the pressure on the BoE

to raise interest rates. The narrative of a central bank constrained by politics has also been confirmed by

Ben Broadbent, the BoE deputy governor, who stated that the next fiscal actions of the government would

influence the BoE decisions.

Conclusions

All in all, Liz Truss' imprudent fiscal policies had negative economic, financial and political consequences

in the short term. From an economic perspective, the government announcements may have

undermined the BoE efforts to contrast the increasing inflation. On financial markets, the pension funds

disaster revealed a structural weakness of the hedging interest rate risk using derivative instruments

such as the IRS. At last, the story of the Truss government was nothing but a perfect example of political

debacle which led to shortest government in the UK history and, as a result, to a consequent loss in the

credibility of the British institutions. Fortunately, the new government of Rishi Sunak seems to be

determined to face the major challenges of a country in severe economic difficulties and to restore the

historical authority of the national institutions.

By Ernesto Bardi, Lorenzo Moretti, Matei Sandru

Sources:

- ECB

- PPF 7800 index October 2022 Update

- Reuters

- Investopedia

- Bloomberg

- Xe

- Financial Times

- The Guardian

- Wall Street Journal

- The Conversation

- The Economist

- ECB

- PPF 7800 index October 2022 Update

- Reuters

- Investopedia

- Bloomberg

- Xe

- Financial Times

- The Guardian

- Wall Street Journal

- The Conversation

- The Economist