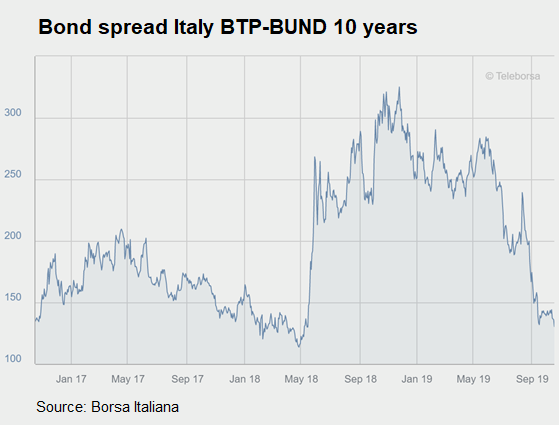

With a public debt ratio of over 120% of GDP, Italy is strongly influenced by the way markets perceive its ability to service that debt. This, in turn, depends strongly on its government policies. The difference between the cost of Italian and German debt (the “spread”) is a reliable indicator of the market’s confidence in the Italian acting government.

I will be examining the change in spread in light of recent changes in the political landscape and gauge the prospects for the Italian economy and funds.

The past government:

Ever since the inception of the coalition government of Salvini’s League Party and Di Maio’s Five-star Movement, and with the ousting of the traditional establishment party (the Democratic Party), instability has plagued the political landscape. Both parties to the coalition have been described as populist, albeit on opposing sides, causing the prospect of a smooth-functioning government to be unlikely from the beginning. However, while the parties did not agree on much, they did agree on some issues.

A rather aggressive anti-EU and anti-establishment rhetoric was quickly established. This immediately frightened markets and, at one point, this became a real threat to Europe as a whole. The hostile relationship between the government and the EU were amplified when Brussels did not approve Italy’s proposed spending budget.

The result was a clear upward push in the spread. In fact, although the spread is never truly stable - as Italy has a long history of uncertainty plaguing the political system and consequently the markets, the indicator jumped up to 268 basis points when the new coalition entered the government. This was very significant compared to an average of around 130 basis points the month before the start of the new government. Throughout the life of the coalition government, the spread eventually reached a peak of around 320 basis points. This is a clear indication of the lack of confidence markets had in the former coalition.

I will be examining the change in spread in light of recent changes in the political landscape and gauge the prospects for the Italian economy and funds.

The past government:

Ever since the inception of the coalition government of Salvini’s League Party and Di Maio’s Five-star Movement, and with the ousting of the traditional establishment party (the Democratic Party), instability has plagued the political landscape. Both parties to the coalition have been described as populist, albeit on opposing sides, causing the prospect of a smooth-functioning government to be unlikely from the beginning. However, while the parties did not agree on much, they did agree on some issues.

A rather aggressive anti-EU and anti-establishment rhetoric was quickly established. This immediately frightened markets and, at one point, this became a real threat to Europe as a whole. The hostile relationship between the government and the EU were amplified when Brussels did not approve Italy’s proposed spending budget.

The result was a clear upward push in the spread. In fact, although the spread is never truly stable - as Italy has a long history of uncertainty plaguing the political system and consequently the markets, the indicator jumped up to 268 basis points when the new coalition entered the government. This was very significant compared to an average of around 130 basis points the month before the start of the new government. Throughout the life of the coalition government, the spread eventually reached a peak of around 320 basis points. This is a clear indication of the lack of confidence markets had in the former coalition.

High spreads are very dangerous for governments and can be the cause of their downfall. This is because the country is not able to finance itself while at the same time servicing the outstanding debt obligations when interest rates are too high.

The effect of recent events on markets was extremely significant: a total of €9 billion have been taken out of Italian funds in the first half of 2019 and much more since the inception of the dysfunctional government.

The fall of the previous government

In a move to increase his seats and to form a new government following many months of conflict within his coalition partner, the former deputy prime minister and head of the League Party, Mr. Salvini, withdrew his confidence, thereby ending the first Conti government. An immediate political crisis ensued, with instantaneous effects on markets and on the spread, which jumped up in mid-August (at the height of the political crisis) while Italy’s benchmark stock market index (the MIB) was falling.

While markets feared a long political deadlock, as is typical in the Italian political system, a new government formed quickly. A new coalition between the Democratic Party and the Five-Star Movement was formed holding a completely different set of agendas with respect to the previous gevernment. Mainly “pro-Europeanism, green economy, sustainable development, fight against economic inequality and a new immigration policy”.

The new government

The new coalition is much more pro-EU, and has in fact received more leeway in the spending budget from Brussels (now Italy is allowed a deficit equal to 2.4% of GDP, slightly larger than before). The credibility of the government is much stronger in Brussels, as their policies are considered more sound. This was highly appreciated by markets and directly visible in the spread.

The higher confidence in the new government coalition, together with public satisfaction with the Prime Minister (Giuseppe Conte) has also been reflected in the stock market, which is now on an upwards swing once again. Also, this positive shift in sentiment was equally identifiable in the spread, which since the new government was formed has fallen again to the long-term average of around 130 basis points.

This facilitates the government’s ability to finance its debts, thereby creating a more favourable situation for the economy as a whole.

What does the future hold?

Italian funds, which took a strong beating during the time of the mis functional coalition, may slightly recover in light of this good news and decrease the overall uncertainty. But, unfortunately, given the nature and fragility of the Italian political system, the future is never guaranteed. In fact, it is important to remember that soon after the creation of the new government, prominent political figure and former prime minister, Matteo Renzi, left the Democratic Party and created his own parliamentarian group. He is clearly aiming at gaining political space in the centre – including engaging in talks again with Silvio Berlusconi’s party. It is not excluded therefore that political instability may become yet again a more prominent risk factor in the Italian economy’s outlook.

Riccardo di Mauro