In 2007 Berkshire Hathaway chairman Warren Buffet bet that over the following ten years a Vanguard fund that tracked S&P 500 index would beat five hedge funds chosen by Protégé Partners, a firm that focuses on emerging hedge fund managers. The result of the wager arrived earlier than expected: at the beginning of the year Ted Seides, former co-manager of Protégé Partners, wrote: “For all intents and purposes, the bet is over. I lost”, and in response Mr. Buffet remarked there was “no doubt that Girls Inc. of Omaha, the charitable beneficiary I designated to get any bet winnings I earned, will be the organisation eagerly opening the mail next January”.

As a matter of fact, the venerable charity will receive a $1 million cheque in January 2018, since none of the funds outperformed the Vanguard from 2008 through 2016. According to Buffet, the five funds gained a 2.2% on a compounded annual basis from 2008 to 2016, while the index fund gained a remarkable 8.54%. In addition, Buffet pointed out the five funds selected by Seides had invested their money in more than 100 funds, meaning a single manager could not distort the final result.

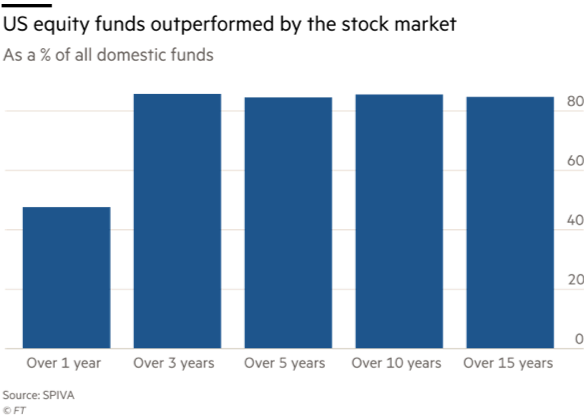

The outcome of the “Buffet Bet” draws the attention on a yet known question regarding the increasing impact of low-cost passive investing since the financial crisis. Investors have increasingly placed trust on Vanguard funds, which track benchmarks on specific indices at low fees rather than paying high-priced money managers who make active picks in the stock and bond markets. The index funds have drawn more money from investors in 2016 than all mutual funds and exchange-rated funds combined, as shown by Morningstar preliminary data. On the other hand, the so called “stock pickers” have been struggling: less than 15% of US stock fund managers have beaten their benchmarks in the last 15 years, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices (SPDJI). Moreover the $3 trillion hedge fund industry could see their assets reduced by as much as 30% in the next three years, as Boston Consulting Group reports.

Nevertheless, active managers should not give up hope: there are initial signals of recovery for the active regime. From June 2016 to June 2017 52.5% of all US equity mutual funds outperformed their benchmarks, according to SPDJI, and on average gained the best result in four years which amounts to 8.6%, according to HFR research group. If it is true that the passive strategies have prevailed from 2009-2016, it must also be considered that historically there has been a clear cyclicality in the leadership between the two, as written by Andrew Folsom, senior investment analyst at Wells Fargo, in a recent report: “We could be in the early stages of an ‘active versus passive’ regime change”.

As a matter of fact, the venerable charity will receive a $1 million cheque in January 2018, since none of the funds outperformed the Vanguard from 2008 through 2016. According to Buffet, the five funds gained a 2.2% on a compounded annual basis from 2008 to 2016, while the index fund gained a remarkable 8.54%. In addition, Buffet pointed out the five funds selected by Seides had invested their money in more than 100 funds, meaning a single manager could not distort the final result.

The outcome of the “Buffet Bet” draws the attention on a yet known question regarding the increasing impact of low-cost passive investing since the financial crisis. Investors have increasingly placed trust on Vanguard funds, which track benchmarks on specific indices at low fees rather than paying high-priced money managers who make active picks in the stock and bond markets. The index funds have drawn more money from investors in 2016 than all mutual funds and exchange-rated funds combined, as shown by Morningstar preliminary data. On the other hand, the so called “stock pickers” have been struggling: less than 15% of US stock fund managers have beaten their benchmarks in the last 15 years, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices (SPDJI). Moreover the $3 trillion hedge fund industry could see their assets reduced by as much as 30% in the next three years, as Boston Consulting Group reports.

Nevertheless, active managers should not give up hope: there are initial signals of recovery for the active regime. From June 2016 to June 2017 52.5% of all US equity mutual funds outperformed their benchmarks, according to SPDJI, and on average gained the best result in four years which amounts to 8.6%, according to HFR research group. If it is true that the passive strategies have prevailed from 2009-2016, it must also be considered that historically there has been a clear cyclicality in the leadership between the two, as written by Andrew Folsom, senior investment analyst at Wells Fargo, in a recent report: “We could be in the early stages of an ‘active versus passive’ regime change”.

First of all, the shift was determined by the lower fees asset managers were forced to apply in order to compete with the cheap passive funds, which eased funds to beat their benchmarks after fees as well. For every $100 invested in US equity funds in 2000, expense ratios amounted to an average of about 99 cents, while in 2016 this figure fell to 63 cents.

Moreover, during the post-crisis years share prices tended to move in unison following the “risk-on, risk-off” phenomenon. The prices reflected economic shocks emanating from the US, Europe or China and the decisions of central bankers who reacted to shocks by increasing the money supply. Although, chief executive of Capital Group Tim Armour says: “We’ve been in a period where correlations were tight, but that’s breaking up. There are more opportunities to differentiate yourself”.

Among the explanations for the “great correlation collapse”, the most likely seems to be this year’s firm and broad-based global economy. Growth rates increased lately, giving space for investors to follow their sentiment rather than undergoing the central banks’ data and utterance.

What results unsure is how long the low correlation US stock market rally is going to last. “Maybe we have two years left, or maybe we have six months. I think we’re talking about less than two years,” says Mr. Sheets. This prediction does not worry certain fund managers who, instead, welcome higher volatility as the proof of worth of stock pickers against simple index trackers.

Isabella Costa