India and China are currently two of the fastest-growing economies in the world, with immense potential for further growth and development. Both countries are home to over a billion people and have recently undergone significant economic transformations, but the approaches taken by each nation are markedly different and that is the main reason why we are witnessing radical changes that could affect the world economy. China has been on a remarkable economic trajectory for several decades, fueled by a combination of State-led industrialization and a vast low-cost labor pool which boosted the industrial economy. As a result, it has become the world's second-largest economy and a global manufacturing powerhouse where multiple companies decided to move to.

In contrast, India has pursued a more market-oriented, democratic path to economic growth, leveraging on its vast pool of young, educated workers and a burgeoning services sector. Although it lags behind China in terms of economic development, India's youthful population and expanding middle class are poised to drive significant growth in the next few decades. However, it faces its own set of challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, a relatively small and inefficient manufacturing sector, and ongoing social and political challenges.

In contrast, India has pursued a more market-oriented, democratic path to economic growth, leveraging on its vast pool of young, educated workers and a burgeoning services sector. Although it lags behind China in terms of economic development, India's youthful population and expanding middle class are poised to drive significant growth in the next few decades. However, it faces its own set of challenges, including inadequate infrastructure, a relatively small and inefficient manufacturing sector, and ongoing social and political challenges.

China’s Demography and Economy

Demography

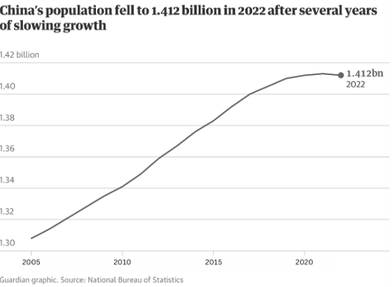

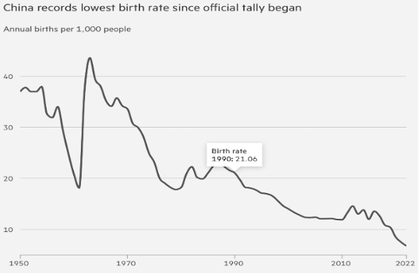

Every year the National Bureau of Statistics of China publishes their annual report, in 2022 their data recognized a new trend, the decline of China’s population. In the previous year it was reported that the population fell by 850.000, with the main driver being lower birth rates. The last time this trend showed up was 1961 due to famines that killed tens of millions of people. This time around, it is China’s birth policies and inability to pick up on 21st century birth rate tendencies that has brought this situation. From 1980 to 2015 China had a one-child policy that limited most families to having only one baby. Nowadays, most Chinese families can have up to three children as the previous policy was changed twice, once in 2015 and again in 2021. Furthermore, some regions are also giving cash to encourage the population to have more babies. One village in southern Guangdong province accounted in 2021 that it would be pay permanent residents with babies under 2 and a half years old $510 per month, which could add up to $15000 per year. Additional government incentives, include supporting maternity leave and reduction in taxes.

China's population

It is important to note that another effect of lower birth rates has also been the change in China’s demographic distribution. Nowadays 1/5 of China’s population is considered elderly. An older and lower population is going to put a lot of pressure on China’s social security system, as there are less workers to fund pensions and health care for the elderly. Age-to-dependency ratio is a good measure of this as it shows the ratio of people who need health related support out of the whole population. This ratio increased from 37% in 2010 to 45% in 2021, meaning that for every 100 people 45 require support. Moreover, China also has the highest death rate since 1970, which could be an effect of the population distribution as an older population is going to lead higher death rates. In 2022 the death rate was 7.37 per 1000 people. Even though the Chinese government started to take measures since mid 2010’s it was not until 2022 that Xi Jinping officially acknowledged that China had a population problem in the 20th National Congress of the Communist party. It remains to be seen if the publicization of this problem and the new policies by the Chinese government will invert the negative population trend.

China's births per 1,000 people

Economy

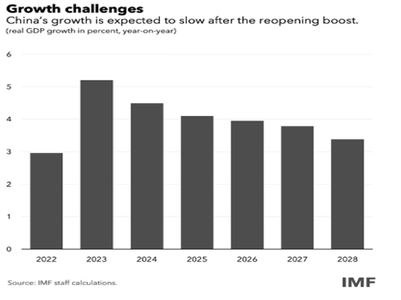

China was hit hard by COVID-19, as its economy was plagued by constant lockdowns in the previous years. This led to an economic growth of only 3% in 2022, but in the short term it is predicted that the economy will rebound, resulting in an estimated growth of 5.2% in 2023. The same cannot be said about the long term, as economic growth is expected to slow down. Due to this trend, there is a high chance that China might enter a period economic stagnation, which happens when economic growth rate is lower than 2-3%. Previous data on this region suggest that stagnation is even more likely in an aging demographic, evident by Japan’s economic stagnation in the 90s.

China's growth

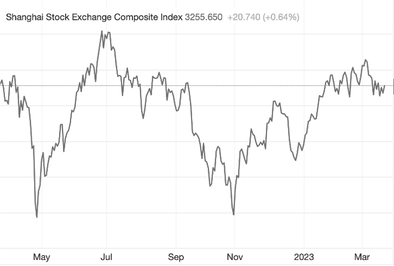

Inflation in China is falling, releasing some of the pressure from the economy and policy makers. This February it fell to 1%, a decrease from the previous month’s 2.1%. This is encouraging, but China still has a lot of issues to deal with. At the moment, it is going through a real estate crisis, where banks have been forced to give mortgages to 70-year-olds. These mortgages often have maturities of 10 to 25 years and if the elderly cannot pay the mortgage their children will have to carry on with the payments. Furthermore, China’s merchandise exports fell by 6%, showing signs of weakness in both the production sector and in demand. As the global political landscape is changing new partnerships have been arising. China’s exports to Russia jumped by 19.8%, for a total of $15 billion and imports increased by 31.3% to $18.65 billion. While China and Russia are strengthening their economic ties, the USA is preparing new rules to prevent tech investments in China. The policy is further going to slow down growth and their market position compared to competitors. This could push companies to speed up their process of transitioning their resources and investments elsewhere, like India. Biden administration has also restricted semiconductor exports to China in another attempt to slow down their technological and economical advancements. The ending of lockdowns rallied the stock market, where especially in January Chinese companies did great. This was not long lived, as now they have lost some of the gains and are at similar levels to December 2022. With that said, they are still doing better than their 6-month low, where stocks crashed after the announcement of new lockdowns in late October 2022. Furthermore, after the National Bureau of Statistics announced that birth rates were lower than previous years, Chinese stocks related to baby goods and other maternity goods fell. For example, Kidswant Children Products’ stock was down 8.5 percent after the news broke out.

India’s Demography and Economy

Demography

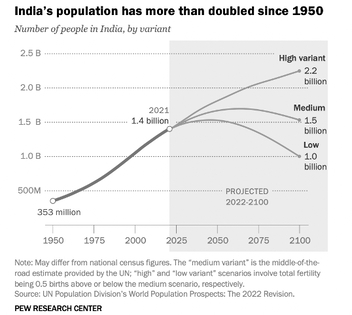

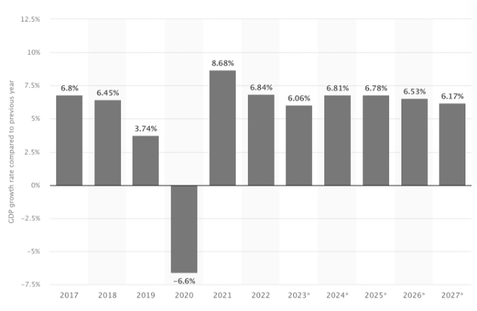

The first relevant population expansion in India was registered in 1918-1919 right after the great influenza epidemic. From that moment to 1961 a steadily accelerating rate of growth was reported, after which the rate leveled off. India’s population doubled between the 1947 and the 1981 census and surpassed 1 billion people by 2001. During the decade 2001-2011 the Indian population has increased by more than 181 million and the growth has remained steady at each decennial census. Since the 1950s, Indian governments have worked to promote a range of birth control methods, some states and territories discouraged large families with penalties and in 2017 India’s Ministry of Health and Welfare launched an all-embracing family program with the aim of bringing fertility down to replacement levels by 2025. Due to these initiatives, there has been a considerable drop in the birth rate, and so the annual pace of population growth has reduced from a 2.3% in the gap between 1972-1983 to 0.98% in 2017. Given that India has not conducted a census since 2011, the exact size of the country’s population is not easily known, but it is estimated to have more than 1.4 billion people and it is expected to become the most populous country in the world by the end of 2023, beating China who has had this supremacy since 1950. Finally, Covid-19 has had a very strong impact on both the population and the economy growth (contracted by 6.6% in 2021), considering that one fourth of the world’s virus cases were registered in these areas.

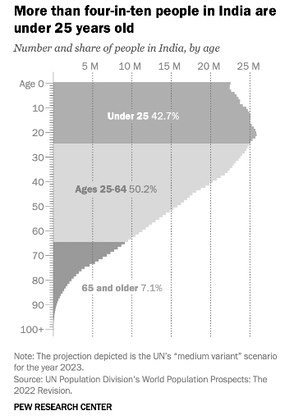

Number and share of people in India, by age

India's population

Economy

Indian population boom in the 20th century concurred with an economic transformation that brought major improvements in life expectancy, living standards and food production. “A lot of the growth in India is driven by finance, insurance, real estate, business process outsourcing, telecoms and IT,” said Amit Basole, professor of economics at Azim Premji University in Bangalore. “These are the high-growth sectors, but they are not job creators.” The population is young, half of the inhabitants is under age 30 and less than one-fourth is age 45 or older but the country’s high-growth economy is failing to create enough jobs, especially for younger Indians.

The IMF forecasts that the economy will expand for a 6.1% this year and 6.8% in 2024, a rate that no other major economy has ever registered. However, jobless numbers continue to rise. According to the data of the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy, unemployment in February was 7.45%, 0.30% higher than the previous month. India bounced back strongly from the coronavirus pandemic, ranking India's economic outlook above every other major country. Therefore, the growth rate has slowed down to 4.4% due to global higher inflation and lower consumption. Moody’s projects a 70 basis points increase in 2023 real GDP growth at 5.5% and 2024 growth at 6.5%, this projection has been raised by the carry-over effects of the second half of 2022 for the 2023. The gross domestic product at current prices is estimated to be at Rs. 232.15 trillion (US$ 3.12 trillion) in 2022. Finally, according to markets, India has the third-largest unicorn base in the world with more than 100 unicorns valued at US$ 332.7 billion and, during the next 10 years the Exchange of Bombay will register a growth of 11% per year, reaching a market capitalization of 10 trillion dollars.

India's GDP growth compared to the previous year

Apple moving from China to India

One of the most important companies marking this evolving situation is Apple. The American company is increasingly shifting the production of iPhones, iPads, and AirPods from China to India. Its major manufacturing partners, such as Foxconn, Wistron, and Pegatron, which already have manufacturing facilities in India, are expected to continue expanding their operations in the country.

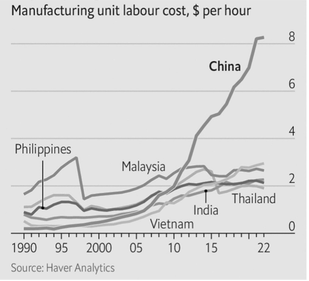

Recent relevant examples are given by the fact that Apple has already produced over 3 million iPhones in India in 2022, up 300% from the production level of the previous year, increasing India's share of global iPhone production, which was just 2% in 2020. Furthermore, Foxconn has won an order to produce 200 million AirPods annually for Apple, along with a $700 million plants investment. This represents a significant change in the global value chain equilibriums, and a remarkable advantageous moment for India. The reasons behind those changes are mainly economically and geopolitically related. First of all, according to a report by Nikkei Asia, the average wage of a factory worker in China has increased by 64% over the past decade, while labor costs in India are still relatively low, making it a more cost-effective destination for large manufacturing companies.

It is also important to remember that India, one of the fastest growing economies in the world, is now the second-largest smartphone market in the world, after China. It provides foreign investors with a skilled workforce, and a favorable regulatory environment. In addition to that, the $26 billion Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme promoted by the Indian government encourages companies to manufacture electronic products. It provides an incentive of 4% to 6% on incremental sales (over base year) of goods manufactured and covered under target segments for a period of five years after the defined starting date. As a result, this South-Asian country has greater potential, both in terms of sales and manufacture. Furthermore, the pandemic and the following demand peaks had disastrous repercussion on supply chains of many producers, especially the ones located in China, due to the zero covid policy. Along with India, Apple is consolidating supplies of components from other countries, such as Taiwan and Japan, to reduce the risks associated with over-dependence on Chinese manufacturing plants. This decision aligns also to the mitigation of adverse geopolitical scenarios, which will see the West countries sanctioning Eastern Russia allies, and China is among one of them. According to a report by the South China Morning Post, Apple's move to shift production of some of its products to India could lead to a loss of up to $15bn in annual revenue for Chinese companies that supply components for these products. On the other hand, the India Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA) stated that Apple's decisions could create as many as 300,000 jobs in India's mobile phone manufacturing industry by 2025. The increasing importance of India in the manufacturing sector could implement up to 8 million new jobs by 2025 and contribute up to $1 trillion to India’s already fast-growing GDP.

How this will shape the future

Production shifts’ effects

As previously discussed, we will most likely observe a radical change regarding the production, especially under the point of view of production sites and direct labor; this will go unnoticed by most consumers even though it will radically impact the costs of productions and the efficiency of big companies like Apple. This significant change is expected to have a substantial impact on both nations since there is a belief that other prominent corporations may follow Apple's lead, further exacerbating the differences between the two countries.

Can India emerge as a rival to China?

One thing is for sure: India cannot afford lost decades, this will not only push it further behind China, but it might also age before it grows rich; it would scuttle its geopolitical ambitions and lock it into a middle-income trap. “The Wire India” carefully analyzed the possible shapes that the Indian economy could take in the next few decades; more precisely, three scenarios were assumed: there is, first, the default business as usual scenario, where the economy trudges along on its present growth path (5.9% avg. 2011-2022). Second, there is a higher growth trajectory that might be achieved through a good policy, leadership, and institutional integrity. Finally, there is what might be called the optimal growth trajectory that the Indian economy has achieved in the past, but, as of right now, may find it difficult to sustain over an extended period going forward. This is the optimal growth scenario with which comparisons with China could possibly be made. The first key point to be made is that while the Indian economy has seen impressive growth, there are still several objectives that need to be accomplished. Moreover, a meaningful comparison with the most advanced Asian economies can only be drawn with a meticulous evaluation of various factors and an optimistic outlook. Assuming that India will soon reach the optimal growth trajectory, it could take China’s role under the technological point of view – for example – or it could also exponentially develop its infrastructures; for decades these two sectors have been globally underestimated, although India has thriving technology industry, with a large pool of skilled professionals and investments in infrastructure (35% of India’s GDP in 2022) and renewable energy. The Wall Street Journal pointed out in a recent article that today’s reality is that the economy – over a small-time window, hypothetically by the year 2035 – needs to create 200 million jobs to employ all working-age Indians. This task is near-impossible, given the history of India’s economic development (especially after the independence from Britain, which led the country to 75 years of profound malfunction) with its emphasis on heavy industry and its scandalous neglect of export-oriented manufacturing, the means by which South Korea and Taiwan, not to mention China, raised themselves to levels of material well-being that vastly overshadow scruffy, argumentative, inefficient, poorly educated India.

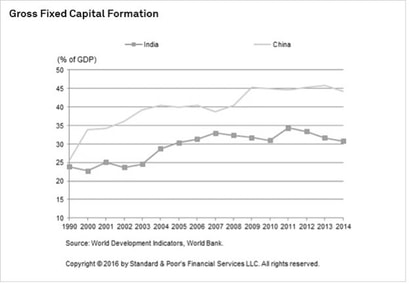

Even though the India’s growth in infrastructure investments might sound impressive with a 35% GDP in 2022, it is still far behind from China, which has been investing 35% - 45% of its GDP for the past 3 decades.

A reduction in labor costs alone is not sufficient to enhance India's manufacturing competitiveness. Without adequate national infrastructure, the effect will not be sustainable. At present, the country's infrastructure is inadequate, and the development of a vibrant manufacturing sector that supports infrastructure development is critical if India is to realize the demographic benefits of gainfully employing its substantial young population. Nonetheless, improving labor productivity and ensuring sufficient employment opportunities will also present significant challenges. The real challenge for the second most populated country in the world will be to adapt its investments and structures to sustain the economic growth that could, hypothetically, be comparable to China’s.

By Ettore Marku, Pietro Casnigo, Andrea Cavenago, Francesca Dini

SOURCES

- Financial Times

- IMF

- CNN

- The Guardian

- WSJ

- Reuters

- The Economist

- Economic Times

- Britannica

- CNBC

- S&P Global