The past few years have represented the biggest challenges to the financial landscape since the 2008-9 financial crisis. Geopolitical instability, rising interest rates, and the fear of a recession have been the main drivers of a slump in deal activity globally. Bloomberg data revealed a decrease of over a third in IPOs during the first half of 2023. JP Morgan Chase CEO Jamie Dimon concluded the recent quarterly results with a warning: “Now may be the most dangerous time the world has seen in decades”.

India’s Economic Challenges in the Global Context

India's economy is impacted by three critical factors. Firstly, the recent invasion of Ukraine has significantly disrupted global markets. This disruption is compounded by the Israel-Palestine conflict, amplifying pressure on India's energy, food markets, and geopolitical ties. In addition to this, the prevailing uncertainty surrounding future interest rates, remaining at elevated levels of 6.5%, only exacerbates these challenges. Companies that previously flourished in the low-interest rate environment following the financial crisis are now struggling to refinance their debt. Furthermore, governments are witnessing a surge in costs related to their pandemic-era borrowings. Finally, the trend of deglobalization has reshaped cross-border deal activities. Several countries and companies are seeking to restructure their supply chains away from China due to the highlighted supply chain risks during and after the COVID-19 crisis. India stands at a pivot point, faced with the decision of its openness to FDIs amidst these shifting global dynamics.

Traditionally, global supply chains prioritised cost efficiency and resource abundance in specific countries, often overlooking geographic distances and cultural disparities. This led to deeply interdependent and concentrated supply chains, with China emerging as the centre of this concentration and companies became heavily reliant on the country. However, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 exposed the weaknesses within these supply chains, particularly as China, the pandemic's epicentre, experienced production halts and transportation disruptions. This underscored the vulnerabilities of the supply chains for the first time. As a result, there was a shift in perspective: the value of supply chain security began to outweigh cost considerations. Companies recognized an urgent need to diversify production networks, leading to the rise of India as a viable alternative.

Moreover, India already has one of the largest transportation networks in the world, with the second largest road network and rail network, as well as the seventh largest civil aviation market, complementing its already substantial shipping infrastructure.

Evolution of India’s Economic Landscape

Over the past decade, Indian government policies have not only attracted Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) but have also facilitated domestic businesses to venture into international markets. Several strategic policy implementations have been essential for these trends. Firstly, the government raised the upper investment limit for automatic overseas approval to $100 million, promoting and incentivizing cross-border mid-market activities. The subsequent policy, initiated in 2005, allowed banks to extend loans to domestic companies for acquiring equity in overseas ventures, streamlining the process and reducing costs for firms to procure funds for international investments. Furthermore, a significant policy change in 2007 involved increasing the limit for overseas investment to 400% of net worth from the earlier 300%, highlighting a shift in the Indian government's risk-appetite and its approach to outward investment, especially as global investors look to India as China’s safer replacement.

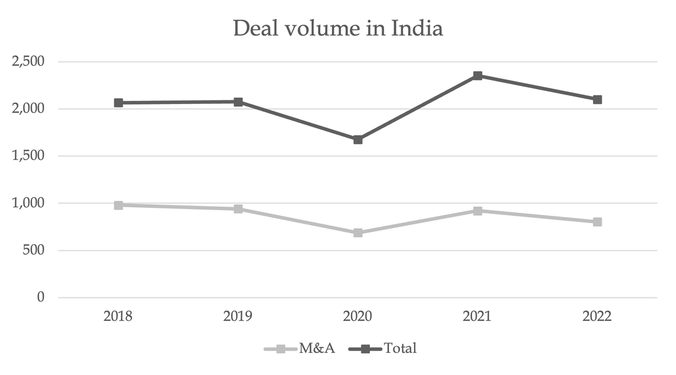

Figure 1 - Evolution of deal volume in India

Additionally, India has seen a rise in so-called megadeals in the M&A sector (transactions of $5 billion or more), with 2018 being a blockbuster year. Walmart’s $16 billion acquisition of Flipkart, an Indian e-commerce company, was the major highlight of that year, essentially kicking off megadeals from foreign investors, which hit their peak in 2021 driven by industry consolidation, particularly within the technology sector. While the Indian Business Optimism Index remains slightly lower than 2021, it still stands close to 2019 levels. This indicates a promising future outlook for the Indian economy.

The realisation of this potential relies on whether the government can leverage India’s economic growth to incentivise FDIs. In addition to this, India’s young demography will be key for a modernisation of its economy. The following paragraphs detail the key elements of India’s economy.

India’s Economic Growth

One of the key characteristics of the Indian economy is the fast growth that it has experienced in the past years. Over the last 4 years, India has ranked 5th globally in real average GDP growth, registering an impressive 6.9%. This growth far exceeds the one registered in China (6.0%) and is much higher than the one of developed economies such as the US (3.3%). This is the culmination of years of increased liberalisation by the government and India becoming one of the top prospects of FDI. Global Pension and Sovereign Wealth Funds have been expanding their footprint in India throughout the last few years and have represented 18% of deal value since 2018, particularly from Canada, Singapore and Abu Dhabi.

Today, three megatrends — global offshoring, digitalization and energy transition — are setting the scene for unprecedented economic growth in the country of more than 1 billion people.

Global Offshoring

Over the years, companies around the world have turned to India for services such as software development, customer service and business process outsourcing since the early days of the Internet. Now, however, tighter global labour markets and the emergence of distributed work models are bringing new momentum to the idea of India as the global back office. Corporate tax cuts, investment incentives and infrastructure spending help drive capital investments in manufacturing, setting India to become the world biggest factory.

Digitalization, Credit and Consumers

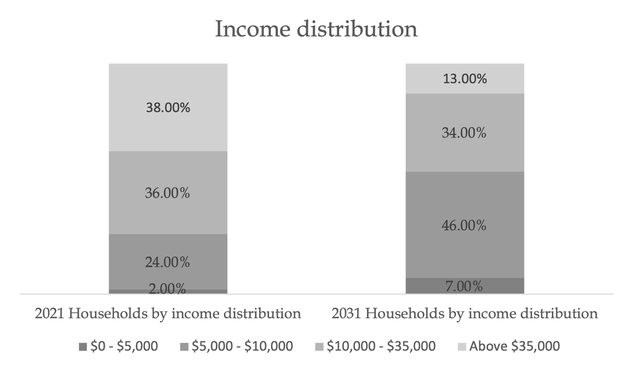

India began laying the foundation for a more digital economy more than a decade ago with the launch of a national identification program called Aadhaar. This initiative is now part of IndiaStack, a decentralised public utility offering a low-cost comprehensive digital identity, payment, and data-management system. IndiaStack has broad applications, including a network for lowering credit costs, making loans more accessible and affordable for both consumers and businesses. Credit availability is an important component of economic growth, and “India is currently one of the most under leveraged countries in the world,” says Desai, whose team thinks the ratio of credit to GDP could increase from 57% to 100% over the next decade. Indian consumers are also likely to have more disposable income. India’s income distribution could flip over the next decade, and overall consumption in the country could more than double from $2 trillion in 2022 to $4.9 trillion by the end of the decade, with the greatest gains going to non-grocery retail, including apparel and accessories, leisure and recreation, and household goods and services, among other categories.

Figure 2 - Projections of the evolution of income distribution in india

Energy transition

Energy is also key to economic development, as it impacts education, productivity, communication, commerce and quality of life. All of India’s 600,000-plus villages have access to electricity, due to recent upgrades to transmission and distribution, among other changes. This could boost India’s daily energy consumption by 60% over the next decade. Although India will need to tap fossil fuels to meet its growing energy needs, an estimated two-thirds of India’s new energy consumption will be supplied by renewables like biogas and ethanol, hydrogen, wind, solar and hydroelectric power. This could reduce India’s reliance on imported energy and improve living conditions in a country that is now home to 14 of 20 of the most polluted cities in the world. It also creates new demand for electric solutions, such electric vehicles, bikes, and green hydrogen-powered trucks and buses.

Ridham Desai, Morgan Stanley’s Chief Equity Strategist for India, states that they believe India is set to surpass Japan and Germany to become the world’s third-largest economy by 2027 and will have the third-largest stock market by the end of this decade. All told, India’s GDP could more than double from $3.5 trillion today to surpass $7.5 trillion by 2031. Its share of global exports could also double over that period, while the Bombay Stock Exchange could deliver 11% annual growth, reaching a market capitalization of $10 trillion in the coming decade. In a new Morgan Stanley Research Bluepaper, analysts working across sectors look at how this new era of economic development could bring about staggering changes: boosting India’s share of global manufacturing (data shows that multinational corporations’ sentiment on the investment outlook in India is at an all-time high. Manufacturing’s share of GDP in India could increase from 15.6% currently to 21% by 2031—and, in the process, double India’s export market share), expanding credit availability, creating new businesses, improving quality of life and spurring a boom in consumer spending.

India's FDI Evolution

Given the rapid growth and innovation of the country, it is not surprising that net new foreign direct investment (FDI) has risen very rapidly in recent years, reaching a record level of $50 billion in 2020. The strongest contributor to FDI inflows has been technology. In particular, the Computer Software and Hardware sector received the largest share, around 25%, of total inflows. Big multinational companies have committed to invest large sums, with “Google for India Digitization Fund” planning to invest $10 billion in India in the next seven years and Facebook planning to invest $5.7 billion in Jio Platforms, an Indian technology company headquartered in Mumbai. The USA, Singapore, Mauritius and United Arab Emirates were the four top sources of inflows in FY 2022-2023. This highlights India's strengthening economic partnerships with global financial hubs in emerging markets on the one side, and strong ties with advanced economies like the USA on the other. These robust FDI inflows have enhanced India's foreign exchange reserves and reduced its external account vulnerability over the last decade.

Global FDI flows dropped by 24% in 2022, to USD 1 286 billion, after large withdrawals of capital by a telecommunication MNE operating in Luxembourg. Excluding Luxembourg, global FDI flows declined by 5% in 2022 compared to the previous year. Major FDI recipients recorded lower FDI flows in 2022, particularly China and the United States partly as a result of reduced new investment activity.

As highlighted in the above graph, OFDI (Outwards FDI) flows increased until 2019, to then experience a sudden decrease in 2020 due to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2021 the metric rebounded, reaching $17,239 billion, and it increased again in 2022 due to the geopolitical uncertainty, further disruption of the supply chain and decrease in M&A deals caused by the Russian-Ukraine conflict.

With respect to inward FDI flaws, the trend has been different: a peak of 64,362bn has been reached in 2020, and the value is now expected to increase again after a drop in 2021. This trend is expected to continue in the future due to India’s high economic growth and favourable policies, and due to investors, who want to diversify their supply chain.

Modernisation of Indian Economy

Fuelled by favourable demographics, India's savings rate is poised to grow as dependency ratios decline, incomes rise, and the financial sector develops further. This is expected to expand the pool of capital available to drive additional investments. Domestic demand has been the major driver of economic growth and the creation of investment opportunities for both domestic and foreign companies. Recent economic indicators continue to signal expansionary economic conditions, especially backed by the financial and business services sector.

Figure 3 - Evolution of the volume of FDIs (inwards and outwards) between 2016 and 2022

Demography is not the only driver of this growth. India has also made some significant progress in innovation and technology. Technology is advancing at a rapid pace across all industries, and the country represents one of the largest services exporters in Information Technology and Business Process Outsourcing. The large pool of employable talent is positioning India as a global technology talent hub and, combined with the large, fast-growing domestic consumer market, it has attracted global corporations to set up their Global Capability Centres (GCCs) in the country. Such centres are specialised facilities that multinational corporations use to centralise and streamline specific business functions or operations. Together, they are expected to employ between 2 and 3 million people by 2025. This is having a multiplier impact on the economy, as the workforce is a large consumer of goods and services and contributes to savings and investments.

Global corporations are not the only ones interested in the opportunities offered by the country’s large consumer market. The strong domestic demand is incentivising well-capitalised Indian corporates to expand their market reach and competitive advantage by acquiring key technology capabilities. An indicator of this has been the number and volume of strategic M&A deals, especially in sectors such as TMT and Financial services. Deals in the TMT sector are primarily driven by the acquisition of technological assets within streaming platforms, healthcare technology, and connectivity. Financial services deals, on the other hand, are driven by portfolio restructuring aimed at leveraging cross-selling opportunities, and investments in fintech and digital capabilities. Fintech partnerships are one of the most active segments of the Indian economy, driven by the growth of digital payments, P2P lending regulations, and unexpected players like telematics apps and e-commerce marketplaces venturing into financial services, presenting significant opportunities in a country where most transactions are still cash-based.

Change in Regulations

India realised it was a big chance to take advantage of the developments and attract companies, mainly from China, to improve the environment for them further, so it accelerated its government-led infrastructure development programmes to bring more companies to the country. One aspect of this initiative is the so-called National Infrastructure Pipeline, through which the government is planning to invest USD 1.4 trillion in infrastructure in the next five years. The main objective is to improve the infrastructure of the following areas—electricity generation, energy storage, waste and water, logistics and transportation, among many others. Transportation is one of the most emphasised areas as India is trying to become a major player in global transport. For example, the country is planning to invest USD 25 billion solely in shipping and port infrastructure.

In addition to investments in infrastructure, India is doing legislative and regulatory changes as well to motivate companies to move to the country by making operations bureaucratically easier and cheaper. One illustrious example is the already implemented Goods and Services Tax, which changed the previous complex tax system full of indirect taxes to a more unified and simplified tax system, with greater transparency and efficiency. A following example is the Make in India campaign. Its main aim is to “transform India into a global design and manufacturing hub”, persuading foreign companies to invest and move production in the country by easing tax levels, regulations and approval procedures, among many other facilitating measures. Several companies relocated their production partially or fully following the above-described developments after the pandemic. Two great examples are investments for the production of the Apple iPhone 14 in India, as Apple is moving some of its production to the country and for the Mercedes-Benz EQS model, the first-ever locally assembled EV in the country.

The establishment of the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016 has been a game changer in creating fierce competition for foreign investors looking to invest in distressed assets. The fact that the number of Asset Reconstruction Companies (ARCs), which essentially buy outstanding debt from banks that they can realise in return for cleaning up banks’ balance sheets, has nearly doubled since 2016 expresses the increased interest in this space. The IBC has resulted in streamlining the insolvency resolution process and has reduced the average duration required for a resolution. Under the IBC the average recovery rate has been 45.2% compared to a paltry 26.7% under the Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act and net non-performing assets (NNPA) are at a 10-year low. These outcomes have meant that India has risen in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business Index, attracting more foreign and domestic investors.

Demography

India’s demographic transition is taking place more slowly than in the rest of Asia, with a more gradual decline in death and birth rates. This implies that the population growth that we have witnessed until now is likely to continue. Ila Patnaik, chief economist at Indian conglomerate Aditya Birla Group, says that India has a working-age population of more than 900 million people that could hit more than 1 billion over the next decade. An indicator that shows how this could benefit India’s economy is the dependency ratio, measured as the ratio of the number of children and elderly to the working-age population. A higher dependency ratio places greater economic and social burdens on the working-age population, potentially leading to reduced economic growth and increased demands for social services. For India, it will be one of the lowest among large economies for at least the next 20 years. This represents a great opportunity for the country to establish robust manufacturing capabilities, sustain the growth of its service sector, and further develop the already mentioned infrastructure.

The demographic features of the country also represent a source of advantages over economic competitors. For example, the median age is only 28.4, compared to 38.4 in China. There is a large portion of entrepreneurial, English-speaking and digitally literate people, which constitutes a remarkable competitive advantage. In 2019, 265 thousand people claimed English as their first language, while 83 million claimed it as their second and there were 720 million internet users. Finally, the cost of labour in India is reasonably cost-effective compared to the skill set of the workforce.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the current economic environment is characterized by uncertainty, brought about by the challenges posed by the Covid-19 pandemic and various geopolitical tensions. This situation is particularly critical for developing countries, as investments are perceived as riskier, leading investors to be cautious in deploying their capital. In this context, creating incentives for investments in the country becomes essential to encourage foreign capital inflows. The Indian government appears to be taking steps in the right direction. Already the fastest-growing economy in the world, India is expected to become the world's third-largest economy by 2027, with a projected GDP of $7.5 trillion by 2031.

By Sara d’Apice, Lorenzo Pastorelli, Mihaly Schieszler, Kabir Wali

Sources

- OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- CFA Institute

- Goldman Sachs

- S&P Global Market Intelligence

- Deloitte

- Ernst & Young