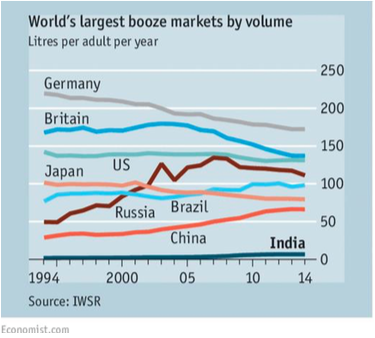

A decade ago, India was among the most promising markets for alcohol producers: rising incomes, young population, changing attitude towards alcohol and a taste for western spirits led several multinationals such as Diageo, Pernod Ricard, SABMiller, Heineken and Carlsberg to bet on it. A decade later, the promise is still there, largely unfulfilled. The percentage of abstemious in India is still far higher than elsewhere but, by fast growing volume, India is the third largest consumer of alcohol worldwide. Indian alcohol market is characterized by a strong preference for strong potions: it is the biggest consumer of whiskey and, when it comes to beer, beers high in alcohol dominate the local market.

A capricious tax and control system.

In a generally difficult environment for business, the alcohol industry faces extra hurdles: influenced by Gandhian austerity, Indian constitution prescribes the government “to endeavour to bring about prohibition” of alcoholic beverages as one of its “primary duties”. This creates the dual policy objectives of deterring drinking while trying to maximise the inflows to the public coffers from related taxes and licences, such as the federal tariff of 150% on imported spirits.

Local licencing fees and taxes, together with state controls, make the final consumer prices five to six times the wholesale price.

Moreover, each of India’s 29 states and 7 union territories have adopted a different approach to alcohol regulation. Gujarat has banned alcohol completely since 1961, drinkers in Mumbai need a licence to consume alcohol and failing to have one is punished with up to 5-years imprisonment. In Delhi, the minimum legal age to drink is 25 years and there is a maximum amount of bottles that can be lawfully kept at home. In April 2016, the state of Bihar imposed renewed bans on alcohol production and sales while the states of Manipur and Mizoram are relieving them. Andhra Pradesh lowered taxes on low-end drinks and increased them on the high-end ones while Punjab levied higher taxes on potions imported from other Indian states. Such protectionist moves force multinationals to have small plants in each state to escape from such import tariffs, hampering the creation of economies of scale.

Tax uniformity is still far to achieve as alcohol was excluded from the new national goods and service reform, aiming to create a single internal market and a national tax system for most of the other goods. In fact, Indian states are highly dependent on revenues from taxation of alcoholic beverages, which constitutes as much as 25% of their revenues.

In many states, alcohol distribution is entrusted to companies owned by regional governments, whose dominant position as gatekeepers allows them to control access to the market and to collect an extra 15-18% of consumers’ prices. According to Deepak Roy, executive vice-chairman of Allied Blenders & Distillers, India’s largest domestic spirits company by volume, this structure “has become a huge political patronage system”.

Something is slowly changing.

In Uttarakhand, multinationals including United Spirits and Pernod Ricard brought the government to court in 2015, after the government set up a state alcohol distribution agency whose officials, the companies claimed, refused to place orders for their brands even when reserve stocks had finished. The court ruled in favour of the MNs, saying that officials had acted in a discriminatory manner.

Past and future.

Drink producers used to be rewarded by double-digit growth in sales as a compensation for the difficult business environment, including a national ban on alcohol advertising and widespread counterfeiting of labelled potions. In the last two years, however, the increase in prices has slowed down sales growth to less than 2%. Last year, SABMiller, which accounts for about 25%of the country’s beer, took a $313m write-down on its Indian investments, citing a reduction in its medium-term growth expectations.

Industry veterans, nonetheless, remain positive on the outlook, claiming that bans are temporary measures that do not pose long-term threats. “In the long term, I’m very optimistic.” – says Mr. Roy. “Drinking is part of the social milieu now. If you want to open

anything — a personal relationship or a business — everything is done over a drink.”

Chiara Cauli