In the midst of the global pandemic, when the slogan is “Stay at home”, India locks its doors even more with a new policy directed at foreign direct investments. The Ministry of Commerce announced that any entity based in or tied to a country “which shares [a] land border with India” will require government approval before investing in an Indian company, a move ultimately aimed at China.

The government’s decision, which was announced on April 18, 2020, will discard fresh investments from companies in the neighbouring countries from automatic approval list, thus with deeper scrutiny. The policy aimed at deterring opportunistic takeovers during the pandemic, as concerns that China would take advantage of low stock market prices to take over strategic industries, and otherwise misuse its ownership, continued to grow.

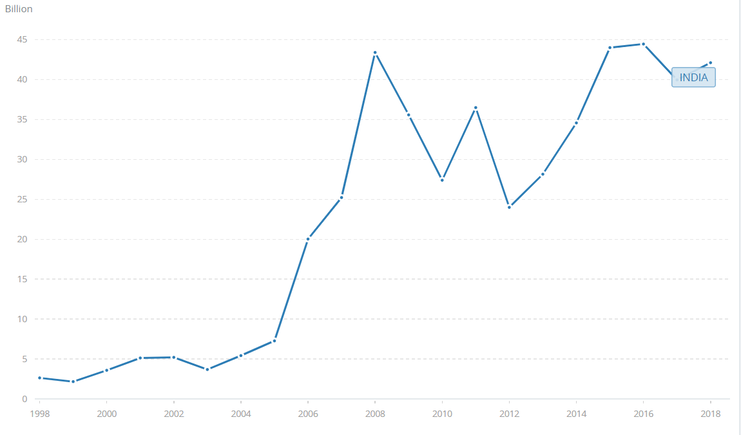

In 2019, India’s inflows were around $49 billion, a 16% increase with respect to the previous year. The majority of these funds went into services industries, including IT. The Indian VC landscape features wealthy individuals and family offices, which are not able to make the commitments needed to finance large start-ups in their early phases. This vacuum is filled by foreign investors, with global giants like the Sequoia or Softbank, which see in India the perfect playground to repeat the success they achieved in China. As a result, Indian start-ups rely disproportionately on overseas VC funding, and all unicorns are foreign-funded.

The government’s decision, which was announced on April 18, 2020, will discard fresh investments from companies in the neighbouring countries from automatic approval list, thus with deeper scrutiny. The policy aimed at deterring opportunistic takeovers during the pandemic, as concerns that China would take advantage of low stock market prices to take over strategic industries, and otherwise misuse its ownership, continued to grow.

In 2019, India’s inflows were around $49 billion, a 16% increase with respect to the previous year. The majority of these funds went into services industries, including IT. The Indian VC landscape features wealthy individuals and family offices, which are not able to make the commitments needed to finance large start-ups in their early phases. This vacuum is filled by foreign investors, with global giants like the Sequoia or Softbank, which see in India the perfect playground to repeat the success they achieved in China. As a result, Indian start-ups rely disproportionately on overseas VC funding, and all unicorns are foreign-funded.

Source: World bank

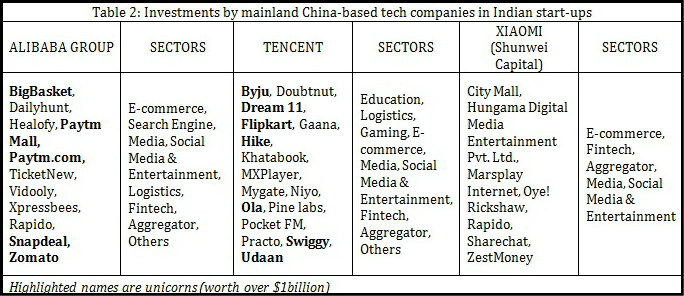

Reported Chinese FDI into India is only $6.2 billion. While China’s presence in the country seems negligible compared to that in other emerging economies, where it invests mostly in physical infrastructure, Indian tech start-ups have attracted increasing funding from the Middle Kingdom, mostly from tech companies such as Alibaba, Xiaomi and Tencent, but also from dedicated VC funds, mostly based in Hong Kong. Official figures also underestimate the actual investment, as they do not include investments made by funds based in Singapore but ultimately under Chinese ownership.

Reported Chinese FDI into India is only $6.2 billion. While China’s presence in the country seems negligible compared to that in other emerging economies, where it invests mostly in physical infrastructure, Indian tech start-ups have attracted increasing funding from the Middle Kingdom, mostly from tech companies such as Alibaba, Xiaomi and Tencent, but also from dedicated VC funds, mostly based in Hong Kong. Official figures also underestimate the actual investment, as they do not include investments made by funds based in Singapore but ultimately under Chinese ownership.

Source: Gateway House

The impact of Chinese funding to Indian tech start-ups is well in excess of the numbers, given the deepening penetration of technology across sectors in the country. This has created concerns for India, especially in relation to data security, propaganda and platform control, which adds up to historically tense relations. Indeed, as the Chinese government has large stakes in or total control of many Chinese corporations, this foreign investment is ultimately seen as political and posing a threat to national security.

India is notorious for arbitrary changes in rules and laws, with track record of letting foreign investors in and then bashing them, as it happened to Walmart, which acquired Flipkart, only to see the GoI change its e-commerce rules, limiting activities by foreign companies.

The Chinese Embassy in New Delhi condemned the rules as being against free and fair trade, reminding that Chinese investment was a main driver behind the industrial development of the country. GoI was reportedly alarmed by the increase in the shares of HDFC, India’s biggest mortgage bank, held by People’s Bank of China’s, from 0.80% to 1.01%. However, this seems more like an excuse, and the decision by GoI was probably meant to be used as a diplomatic lever with Beijing.

The sell-off in the Indian stock market caused by COVID-19 has left many companies in need of funds, and the new rules will most likely worsen this situation as they will slow down investment timelines. Indeed, legal experts estimate that under the new policy approval timelines for fresh investments will take as much as eight months, in contrast to the current 6-8 weeks for approvals of typical Chinese investments. However, existing investors are offered protection by their contracts and government trade deals.

While also the EU shares the fears of Chinese takeovers, the immediate and long-term effects of this new FDI rule require more attention, as they put strain on companies exactly when the coronavirus outbreak has already hit them hard. Is it advisable to initiate cold wars of this kind in a period of global weakness?

Camilla Gaetani

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.

The impact of Chinese funding to Indian tech start-ups is well in excess of the numbers, given the deepening penetration of technology across sectors in the country. This has created concerns for India, especially in relation to data security, propaganda and platform control, which adds up to historically tense relations. Indeed, as the Chinese government has large stakes in or total control of many Chinese corporations, this foreign investment is ultimately seen as political and posing a threat to national security.

India is notorious for arbitrary changes in rules and laws, with track record of letting foreign investors in and then bashing them, as it happened to Walmart, which acquired Flipkart, only to see the GoI change its e-commerce rules, limiting activities by foreign companies.

The Chinese Embassy in New Delhi condemned the rules as being against free and fair trade, reminding that Chinese investment was a main driver behind the industrial development of the country. GoI was reportedly alarmed by the increase in the shares of HDFC, India’s biggest mortgage bank, held by People’s Bank of China’s, from 0.80% to 1.01%. However, this seems more like an excuse, and the decision by GoI was probably meant to be used as a diplomatic lever with Beijing.

The sell-off in the Indian stock market caused by COVID-19 has left many companies in need of funds, and the new rules will most likely worsen this situation as they will slow down investment timelines. Indeed, legal experts estimate that under the new policy approval timelines for fresh investments will take as much as eight months, in contrast to the current 6-8 weeks for approvals of typical Chinese investments. However, existing investors are offered protection by their contracts and government trade deals.

While also the EU shares the fears of Chinese takeovers, the immediate and long-term effects of this new FDI rule require more attention, as they put strain on companies exactly when the coronavirus outbreak has already hit them hard. Is it advisable to initiate cold wars of this kind in a period of global weakness?

Camilla Gaetani

Want to keep up with our most recent articles? Subscribe to our weekly newsletter here.