The framework

Inflation is the increase in general price levels of goods and services within a period of time. Most developed-world central banks aim for prices to increase by 2% a year, a level at which consumers do not perceive changes in prices that can noticeably affect their consumption patterns. While since the middle of the 2010s, inflation rates have been below central banks’ targets, the COVID-19 pandemic may have caused the era of low inflation to end, especially in the United States and other American countries.

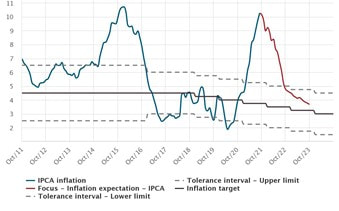

A country that has historically suffered from inflation issues is Brazil, and the situation there seems to have once again worsened. Brazil is a member of the so-called BRIC states along with Russia, India and China. It is one of the largest economies of the world, but it is struggling due to an on-going recession. In September 2021, inflation reached 9.68%, an inflation level that is much higher than the Banco Central do Brasil’s 3.75% inflation target for 2021. The reopening of the economy, global supply issues, the effects of a weaker currency, and a drought continue to weigh on prices.

Inflation is the increase in general price levels of goods and services within a period of time. Most developed-world central banks aim for prices to increase by 2% a year, a level at which consumers do not perceive changes in prices that can noticeably affect their consumption patterns. While since the middle of the 2010s, inflation rates have been below central banks’ targets, the COVID-19 pandemic may have caused the era of low inflation to end, especially in the United States and other American countries.

A country that has historically suffered from inflation issues is Brazil, and the situation there seems to have once again worsened. Brazil is a member of the so-called BRIC states along with Russia, India and China. It is one of the largest economies of the world, but it is struggling due to an on-going recession. In September 2021, inflation reached 9.68%, an inflation level that is much higher than the Banco Central do Brasil’s 3.75% inflation target for 2021. The reopening of the economy, global supply issues, the effects of a weaker currency, and a drought continue to weigh on prices.

A tighten monetary policy

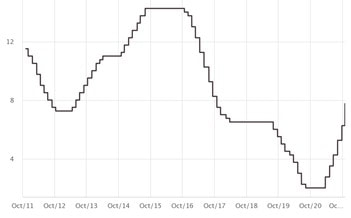

The Monetary Policy Committee (Copom) of the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) has responded with a tightening of the monetary policy to make inflation converge back to the target path. They have raised the Selic interest rate, which is the Brazilian federal funds rate, five consecutive times this year. On October 27th, during their last meeting, they decided to increase the Selic rate to 7.75% p.a.

Copom also expects to raise interest rates again in the future, reaching 8.25% by the end of 2021 and 8.50% in 2022. With this path for the Selic rate, the Copom’s inflation projections stand around 8.5% for 2021 and into the tolerance interval for 2022.

The Monetary Policy Committee (Copom) of the Banco Central do Brasil (BCB) has responded with a tightening of the monetary policy to make inflation converge back to the target path. They have raised the Selic interest rate, which is the Brazilian federal funds rate, five consecutive times this year. On October 27th, during their last meeting, they decided to increase the Selic rate to 7.75% p.a.

Copom also expects to raise interest rates again in the future, reaching 8.25% by the end of 2021 and 8.50% in 2022. With this path for the Selic rate, the Copom’s inflation projections stand around 8.5% for 2021 and into the tolerance interval for 2022.

Figure 1 - Annual inflation rate and market expectations

Source: Banco Central Do Brasil

Source: Banco Central Do Brasil

Figure 2 - Target for federal funds rate (Selic) - annual

Source: Banco Central Do Brasil

Source: Banco Central Do Brasil

The reasons behind Brazilian inflation

But let us have a more detailed look on the causes of the inflation in Brazil.

One of the first reasons for rising prices is that the economy is starting to pick up after the Covid19-crisis. This development has been supported by the acceptance of vaccination by the population: up to October 27, 2021, 55.27% of the population got their second injection, while 19.12% got their first shot.

One of the drivers of the current inflation is also the rise in energy prices (up by 30% over the course of the year). After missing rainfalls caused a drought, which has almost been the worst in the past hundred years, Brazil’s main energy source - hydroelectric power - has been unable to live up to production expectations. The prolonged drought left the country’s huge water reservoir levels 25% below their five-year average by the beginning of October. Energy prices are by now up 30% compared to the beginning of the year. The drought also has effects on prices of agricultural products like rice (11% price increases since the beginning of the year), sugar (up 26%), coffee (up 56%) and meat (up 25%).

Another problem fuelling Brazilian inflation is also the disruption of the global supply chain, which has effects on the inflation rate in most countries these days. In Brazil this can be seen for example with the supply of cooking gas, whose price is up 35% since the beginning of the year.

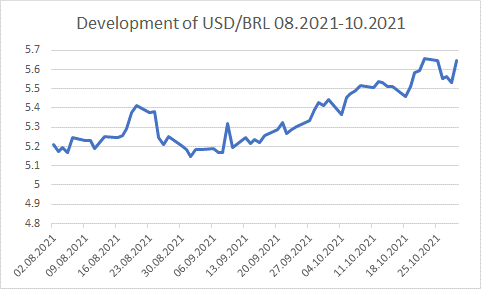

Furthermore, the Brazilian real was weakened in the past quarter due to political conflicts between the president Jair Bolsonaro as well as his supreme court judge. Because a lot of consumer prices are in USD, this is additionally fuelling inflation.

But let us have a more detailed look on the causes of the inflation in Brazil.

One of the first reasons for rising prices is that the economy is starting to pick up after the Covid19-crisis. This development has been supported by the acceptance of vaccination by the population: up to October 27, 2021, 55.27% of the population got their second injection, while 19.12% got their first shot.

One of the drivers of the current inflation is also the rise in energy prices (up by 30% over the course of the year). After missing rainfalls caused a drought, which has almost been the worst in the past hundred years, Brazil’s main energy source - hydroelectric power - has been unable to live up to production expectations. The prolonged drought left the country’s huge water reservoir levels 25% below their five-year average by the beginning of October. Energy prices are by now up 30% compared to the beginning of the year. The drought also has effects on prices of agricultural products like rice (11% price increases since the beginning of the year), sugar (up 26%), coffee (up 56%) and meat (up 25%).

Another problem fuelling Brazilian inflation is also the disruption of the global supply chain, which has effects on the inflation rate in most countries these days. In Brazil this can be seen for example with the supply of cooking gas, whose price is up 35% since the beginning of the year.

Furthermore, the Brazilian real was weakened in the past quarter due to political conflicts between the president Jair Bolsonaro as well as his supreme court judge. Because a lot of consumer prices are in USD, this is additionally fuelling inflation.

Figure 3 – Evolution of the exchange rate USD vs Brazilian Real

Source: Yahoo Finance

Source: Yahoo Finance

Additionally, the upcoming elections in Brazil and the corresponding election campaigning of Jair Bolsonaro increase fear about rising prices. As the unemployment rate in Brazil is still above pre-Covid19-levels at 13.2% and thereby quite high, the President wants to increase welfare payments to the poor portion of the population. This is closely linked to Brazil’s household. In order to cap sovereign debt Brazil has introduced a fiscal ceiling in 2016, which limits its yearly spending budget. This ceiling is adjusted for inflation on a yearly basis and was set at 1.485 trillion reais ($275 billion) for 2021, 31 billion reais more than 2020. The president's plans would require this ceiling to be lifted further and the concrete risk is that the lifted ceiling and the corresponding elevated household spending would in its turn increase inflation further.

But which effects will inflation have for the future?

Following Brazil’s financial and fiscal crises in 2014-2016 resulting in a severe drop in GDP, Brazil’s recovery had maintained stability until 2020 due to the fiscal reformations that reshaped government spending. Those were especially focused on lessening the impact of inflation on commodity prices. Until the pandemic, Brazil’s closed economy model relied heavily on agricultural production and benefited from a global rise in prices following China’s growth, which in turn positively affected internal growth. This trend, however, was reversed during Covid.

Additionally, the energy crisis resulted in power tariffs being raised, which in turn increased production costs for various industries. Researchers estimate that Brazil’s water crisis may last until 2023, as hydroelectric plants struggle to match the increase in demand. The main issue arises when considering rationing, since a 10% reduction in energy consumption could reduce GDP growth by an 1% point, further hindering growth. This duality of sacrificing growth to slow down inflation will continue to worsen Brazil’s economy until the energy crisis is solved.

Household consumption, the second factor highly affected by a rise in inflation, has shifted in several ways over the past months in order to adapt to commodity prices. Gas prices influenced many to seek alternative forms of energy. Furthermore, meat consumption has dropped to its lowest level in 25 years, as most families could not adapt to the 38% increase in meat prices over 2020. All this, coupled with currency concerns related to a global drop in food consumption, indicate that Brazil’s household spending will also remain concerningly low until supply-chain issues related to Covid dissipate and consumption returns to normal pre-Covid levels.

Overall, the current Brazilian inflation problem has demonstrated the importance of restrained government spending and energy price regulation in times of crises, as the country’s economy signs of recovery for the near future are not sufficiently good. This problem, coupled with political issues, may remain prominent for the country’s development in the next few decades.

Following Brazil’s financial and fiscal crises in 2014-2016 resulting in a severe drop in GDP, Brazil’s recovery had maintained stability until 2020 due to the fiscal reformations that reshaped government spending. Those were especially focused on lessening the impact of inflation on commodity prices. Until the pandemic, Brazil’s closed economy model relied heavily on agricultural production and benefited from a global rise in prices following China’s growth, which in turn positively affected internal growth. This trend, however, was reversed during Covid.

Additionally, the energy crisis resulted in power tariffs being raised, which in turn increased production costs for various industries. Researchers estimate that Brazil’s water crisis may last until 2023, as hydroelectric plants struggle to match the increase in demand. The main issue arises when considering rationing, since a 10% reduction in energy consumption could reduce GDP growth by an 1% point, further hindering growth. This duality of sacrificing growth to slow down inflation will continue to worsen Brazil’s economy until the energy crisis is solved.

Household consumption, the second factor highly affected by a rise in inflation, has shifted in several ways over the past months in order to adapt to commodity prices. Gas prices influenced many to seek alternative forms of energy. Furthermore, meat consumption has dropped to its lowest level in 25 years, as most families could not adapt to the 38% increase in meat prices over 2020. All this, coupled with currency concerns related to a global drop in food consumption, indicate that Brazil’s household spending will also remain concerningly low until supply-chain issues related to Covid dissipate and consumption returns to normal pre-Covid levels.

Overall, the current Brazilian inflation problem has demonstrated the importance of restrained government spending and energy price regulation in times of crises, as the country’s economy signs of recovery for the near future are not sufficiently good. This problem, coupled with political issues, may remain prominent for the country’s development in the next few decades.

Sources

By Nelly Eggert, Margherita Magenta, Ana Leticia de Souza Raposo

- Financial times

- Wall Street Journal

- Yahoo finance

- Banco Central Do Brasil

- Macro Trends

By Nelly Eggert, Margherita Magenta, Ana Leticia de Souza Raposo